|

Paper 1

The Allemande Figure in English Regency Dancing

Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor

[Published - 18th September 2013, Last Changed - 27th November 2021]

The Allemande figure can be a challenge for interpreters of

historic dance. It first appears in English dance sources around the year 1770, it remained an important figure throughout the greater Regency era. In this post we'll look at the history of the Allemande figure and

offer advice for how to interpret it.

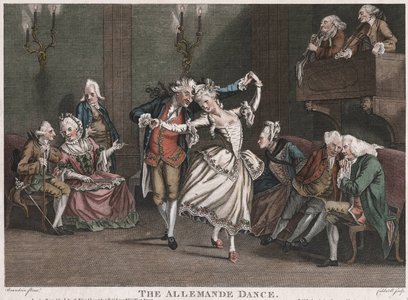

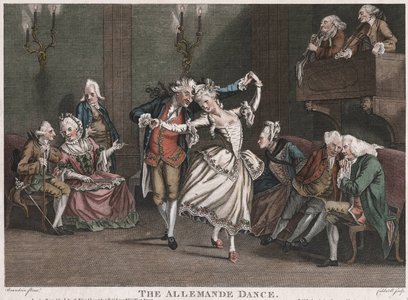

Figure 1. The Baroque Allemande Dance, Caldwell 1772. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Let's start by reviewing some contemporary instructions printed in

England that define the Allemande figure. I've found written

descriptions for six figures:

Giovanni (later Sir John) Gallini, writing c.1772, described a Cotillion dancing allemande: “this figure is

performed by interlacing your arms with your partner's in various

ways”1. I'll refer to this variant as

the Baroque Allemande.

An anonymous writer using the initials F.P. (possibly Francis Peacock?) described a 1772 hybrid Country Dance which included elements of Cotillion dancing, the allemande figure was described as: The allemandes are performed by a gentleman and a lady interlacing arms. When they have to go round to the right, the gentleman with his right hand receives the lady's left behind her; and she with her right behind him receives his left. When they have to go round to the left, they present the contrary hands. It must be observed, that their arms are to pass before each other. When they have to go forward, if the lady be on the right of the gentleman, he with his right-hand receives her right-hand behind her, and she his left behind him; but when the lady is on the left of the gentleman, he with his left receives her left, and with his right her right also behind. (The Lady's Magazine, Vol 3, 1772). I'll refer to this as a Crossed Allemande.

James Fishar, writing c.1773, offered: each Gentleman takes the Right and Left Hands of the Ladies with theirs, the Right Hand above and the Left under, and then make them turn under both Arms, as a Figure Allemande . I'll refer to this two-handed over-head variant as Fishar's Figure Allemande2.

Several writers mention a single-handed figure loosely described as a Pirouette. A c.1830 work attributed (probably incorrectly) to Thomas Wilson names this figure the Pas d'Allemande3 (I'll call it the Pirouette Allemande). It says: “The gentleman

turns the lady under his arm”.

This figure was also described by G.M.S. Chivers in his 1822 The Modern Dancing Master. Chivers wrote that the Allemande is to turn the lady under the arm . It also appeared in Wilson's 1822 Quadrille Fan, where Pas d'Allemande is described as Gent passes the Lady under either arm . Wilson explained it further in his Quadrille and Cotillion Panorama, he wrote that it's a movement of the arms, where the Gentleman takes either Hand of the Lady and passes her under his arm, on either side .

This figure appears to differ from Fishar's Figure Allemande by the number of hands that are joined, though both variants involve an over-head turn.

James Fishar writing c.1773 described a second Allemande variant: each Gentleman makes the Allemande with the Lady that stands upon the Left, with the Right Hand, and turn quite round . This description is vague, it seems to be a variant of the Pirouette Allemande; it's one handed, but perhaps the man walks around the lady (or they turn around each other).

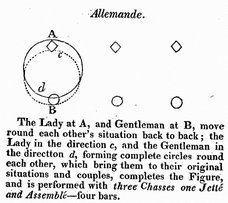

Thomas Wilson, writing in 1808, offered a simple country dancing allemande: “The Lady and

Gentleman pass round each other, returning to their situations”4.

I'll refer to this as the Back-to-Back Allemande. The partners don't hold hands in this variant. He described the figure in more detail in the later revisions of that same book.

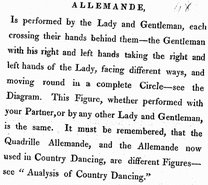

Thomas Wilson, writing c.1818, offered a Quadrille dancing allemande which: “is

performed by the Lady and Gentleman, each crossing their hands

behind them; the Gentleman with his right and left hands taking the

right and left hands of the Lady, facing different ways, and moving

round in a complete Circle”5.

I'll follow Wilson's convention, and refer to this as the Quadrille

Allemande. Wilson explained that this figure was

different from the figure used in Country Dancing, and that the two

should not be confused (See Figure 5); it appears to be the same figure as the Crossed Allemande above.

This figure was also described by an anonymous American writer known as Saltator in 1807. He wrote: put one hand behind and

reach the other out sideways, turning both palms backwards matching another

persons presented in like manner, and arms interweaving with them 6

It's clear that these various assorted allemande figures can be quite different to each

other; they share the same basic name and most involve some fancy use of the arms, most published dances offered no further assistance to the reader in selecting between them.

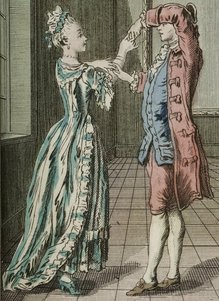

Figure 2. The Baroque Allemande Dance, Guillaume 1770.

The History of the Allemande

The Baroque Allemande Dance

The Allemande figure seemingly arrived in England from France in the late 1760s; the term itself is immediately derived from the Allemande Dance, a Waltz like couple-dance with

intricate passing figures. This dance is understood to have originated in Germany but was perhaps best

documented by French writers. The National Library of France have a

beautiful copy of a 1770 book containing 12 illustrations of The

Allemande Dance7. If you follow the link you can browse the illustrations for yourself. You'll notice that they all

involve an interweaving of arms. One of these images is reproduced

in Figure 2.

Monsieur Gherardi published his Twelve new Allemandes and Twelve new Minuets in London in 1770 (The Public Advertiser, 16th March 1770). It included an essay on the Allemande dance, he hinted that it had first been danced in London in 1768: The satisfaction, which every one expressed, who saw the Allemande Dances two Years ago, gave me room to hope a diversion, so much in fashion throughout the major part of Europe, would, at last, take place in the public, and private Balls of this kingdom also . He went on to describe his own tuition for this dance, including the need for a light grip: the Gentleman and his Partner must never close their hands, or fingers; they must, on the contrary, keep them almost disengaged so as to turn easily and referenced his Troteuse (trotting), Sauteuse (leaping) and Boiteuse Allemande variants. He expressed particular concern for the clothing and hair of the dancers: the passes to be rejected, are such as, where the Body being half bent, the Man turns three or four times round, under his own and the Lady's Arms; a Position which, besides the indelicacy of it, subjects her to the almost inevitable necessity of spoiling her cloathes by the Powder and Pomatum in his Hair; not to mention the consequent disagreable discomposure of that material part of the dress of the Gentleman; giving his Head the same elegant appearence as if he had just popped it out of a Sack .

Gherardi explained that the Allemande dance was popular in Strasburg and Paris, he hoped it would go on to become popular in Britain. I've not located any British references to the Allemande dance prior to 1768, one 1768 reference described it as a new Dance called the Allemande (Oxford Journal, 10th December 1768). The Allemande dance appears to have arrived in England around the same time as the Cotillion dance; indeed, the Allemande Cotillion was sometimes distinguished as a unique dance in its own right.

The wonderful Print collection at Yale's Lewis Walpole Library includes a 1772 image of an

English Allemande Dance8 (See Figure 1). It shows a

travelling figure where the couple intertwine their raised arms. It's unclear whether Gallini's description of the Allemande figure

is an explicit reference to the Baroque Allemande Dance, but his

Allemande Cotillion9 contains a

travelling figure similar to that depicted in the 1772 print. Gallini

was a nobleman (by marriage) and was writing for an aristocratic audience; it's likely

that he intended his Cotillion to use similar figures to those of the contemporaneous Allemande Dance.

The Allemande Dance was a direct precursor to the Waltz. Figure 3 shows a 1797 Cruickshank illustration called The Allemande

that depicts an Allemande variant similar to the later Waltz imagery10, perhaps inspired by the Waltz dance that was beginning to gain popularity in England from around the start of the 19th Century.

Cotillion Allemandes

The Allemande figure, distinct from the Allemande Dance, is referenced in French dance sources before it is known to have arrived in England. It began to appear in Cotillon dances published in England in the late 1760s.

The French writer De La Cuisse described the Allemande figure in his 1762 Le répertoire

des bals as:

“Les Allemandes sont des entrelas de deux figurans, lesquels

ainsi enchaines tournent ensemblent”11.

With a little assistance from Google Translate I've rendered this text

into English as: “The Allemande involves two intertwined dancers,

who are chained and turn together”. This description is a little vague, it's compatible with most our Allemande variants.

Figure 3. The Allemande as a precursor to the Waltz, Cruickshank 1797.

James Fishar used his own overhead Figure Allemande in one of his c.1773 Cotillions named Les Religieuses; or, The Nuns . He didn't restrict himself to a single interpretation of an allemande however, he described a second Allemande in a cotillion named La Favorite; or, The Favourite as each Gentleman makes the Allemande with the Lady that stands upon the Left, with the Right Hand, and turn quite round . This (presumably) single handed allemande appears to be a variation of our Pirouette Allemande figure.

The earliest example of an Allemande figure that I've found in any English

publication is within Longman's Allemande Cotillion, it was advertised as being available for purchase in 1768 (Gazetteer & New Daily Advertiser, 27th October 1768). Longman's figure is described as follows: “The four Gentlemen

give their right Hand to the next Lady & turn her under the Arm

in making a whole round”12.

This figure wasn't explicitly named as an Allemande , but as the entire dance is named the Allemande Cotillion the clue is in the title. Longman's Allemande appears to have been our Pirouette Allemande ; it seems to differ from Fishar's Figure Allemande in the number of hands that are held (and perhaps also in the dancers changing places).

Several different Allemande figures were in use for Cotillion dances of the early 1770s; they all involve the intertwining of arms and turning much like the Baroque Allemande Dance. Indeed, one might almost distinguish the Allemande Cotillion as being a different dance form from the regular Cotillions , some of the early publishers of Cotillions did so.

English Country Dancing

The Allemande's first appearance in English dances may have been in the c.1767 Cotillions, but it rapidly transitioned to English Country Dancing. The first example I've

found of an Allemande in a Country Dance is in the figures of a 1769 dance named The Scotch Lilt13.

Two authors had written about english country dancing in some detail prior to this date, first Nicholas Dukes in 1752 then the anonymous A.D. writer in 1764; neither mentioned the existence of the Allemande figure despite seeking to catalogue the entirety of Country Dancing at their respective dates. It is therefore probable that the Allemande figure arrived in Country Dancing in the late 1760's; it went on to appear in many Country Dance choreographies from the mid 1770s onwards.

Aside: an intriguing undated document exists named A Variety of English Country Dances for the present year, by Cards published by Matthew Welch; it includes a dance called The Chamberlain Election which includes an Allemande figure, the publication is usually dated to 1767 (the date at which Welch claimed on the cover to have opened his academy) and so it could represent an earlier first use of the Allemande figure. The associated diagrams indicate that the Allemande is a turn in which the partners cross arms, perhaps as in our Crossed Allemande . Welch published dozens of adverts for his academy in the London press over a period of 25 years, in most of them he quoted the 1767 date at which it started and no other date... so the presence of that date on the cover is not a convincing date of publication. I suspect that this interesting work dates to late 1776 (that's the date at which The Westminster Magazine published a copy of Welch's Chamberlain Election).

Figure 4. The Allemande in Wilson's Complete System of English Country Dancing, c.1816

The mysterious F.P. writer published a fascinating essay on a newly invented type of dance in the third volume of The Lady's Magazine in 1772. This novel dance form combined characteristics of a Cotillion with those of a Country Dance; it also included an extensive description of the allemande figure, we've described it as the crossed allemande above. This text is the first non-trivial description of the figure that I know of, it was sufficiently exotic that the author felt that the figure needed explaining to their readership. In addition to an allemande-turn it also described a figure for allemanding forwards (a movement more generally referred to as a promenade by later writers); the allemande was clearly considered to be entering into country dancing from cotillion dancing.

Early Allemandes in country dancing appear to require some variant of the figures that were used

in Cotillion dancing, not the much simpler figure described by Thomas Wilson from 1808 onwards. For example,

Skillern and Straight's 1775 Bevis Mount includes

the instruction “Allemand half round to the right, cast up 1

couple; Allemand half round to the left, cast down 1 couple”14.

Wilson's 1808 figure was a simple Back-to-Back or Dos-a-Dos; a half

Dos-a-Dos doesn't make sense so a Crossed Allemande seems more

reasonable. Another 1769 dance named The King of Denmark's Favourite from Thompson's Twenty Four Country Dances for the Year 1769 includes the instruction the first Man take his Partner with his left hand behind and turn her quite round , this could be a description of the Pirouette Allemande figure. Charles Metralcourt in his 1793 Country Dance Love a la Mode featured the figure the six allemande with right and left hands which clearly couldn't be Wilson's figure. Wilson himself wrote c.1818 that “It

must be remembered, that the Quadrille Allemande, and the Allemande now

used in Country Dancing, are different Figures.” (See Figure 5); I've

emphasised the word 'now', it hints that other Allemande variants had formerly been used in Country Dancing but that the modern (for Wilson) convention had changed. I've seen the phrase Allemand over the head used in country dances of the 1770s (such as The Feathers, from the Thompson collection of Twenty Four Country Dances for 1776, or Rutherford's c.1773 La Nouvelle Gardelle), and Allemand with right hand half round (such as in Ashley House, from the Cahusac collection of Twelve Country Dances for 1795). A further variant is Allemand once round (as in The Youthful Frolick from the Cahusac collection of Twelve Country Dances for 1797). Skillern & Straight's 1775 Black Dance includes the instruction ... then the top Cu & 3d turns first right hands behind then left which appears to be another allemande-esque figure (with thanks to the Thoughts on Dance website for pointing it out). A c.1773 country dance named Allemande Spa from the Rutherford collection even refers to use of the Allemande Step thereby hinting that some uses of the word allemande refer to the feet rather than the complicated interleaving of arms.

If we assume that Wilson's interpretation of Allemande was representative of the entire industry at his early 19th century date, then at some point the prevailing use of the figure must have changed. The Back-to-Back was an established

figure in English Country Dancing long before the arrival of the term Allemande , the anonymous A.D. writer defined the Back-to-Back in 1764 as

“This is no more than the man and woman both moving forwards,

then a little sideways to the right, and again straight backwards”15.

Wilson's 1808 description of the Allemande is a little vague, he

explained it further in c.181616 (see Figure 4).

It's clear that Wilson considered the Country Dancing Allemande to be equivalent to the Back-to-Back figure described by A.D., though perhaps with an emphasis on curved movement.

Wilson made this even clearer c.1818 when he

described the Back-to-Back Quadrille figure as: “The movement of this figure is the

same as the "Allemande" in English Country Dancing”17.

Perhaps social dancers found the interlocking of arms a little too complicated and routinely simplified the figure, or perhaps the speed at which the music was played became too fast to accommodate fancy turns. It's likely that any such change was gradual, the word Allemande will have implied different things to different communities over time.

This makes things difficult for an interpreter of historic dance - we

don't know what the original choreographer intended

to be understood by the Allemande figure. We know to use Wilson's

Back-to-Back Allemande in Wilson's own country dances, it's less clear what to use

for other dances. A 1775 dance like Bevis Mount may

use a Crossed Allemande , but what about an 1802 dance like the

Duke of Kent's Waltz18?

Most reconstructions use a variant of a Pirouette Allemande figure in this dance; there's no way to know how the original Cahusac publishers intended the figure to be understood, it may have been an over-head pirouette allemande (they explicitly used an allemande with right hand and left figure in an 1803 dance called The Turnpike Gate) or Wilson's Back-to-Back Allemande, or something else again. Their 1797 The New Forest appears to have featured two different types of Allemande within a single choreography. We've considered this question further elsewhere.

It's likely that there were further allemande variations in use for country dancing. I've encountered two such dances in Thompson's Twenty Four Country Dances for the Year 1787 that use the term Allemande in additional ways; a dance named The Royal Grove includes the instruction Lead up with allemande passes and a dance named The Romp contains the instruction the 1st couple go round with the allemand till they come to their places again, the 2nd and 3rd couples follow . These figures seem to involve travelling rather than a complex turn in place, so perhaps the figure better known as the promenade . I'd be surprised if further examples can't be found.

The Waltz entered English Ballrooms from the start of the 19th century. This dance

developed elsewhere in Europe but it had its origins in the complex

intertwining of arms from the earlier Allemande Dance. Wilson published

several collections of Country Dance Waltzes from 1815, including his Le Sylphe collection for 181819.

These dances featured complex Waltz turns that are distinct from the Back-to-Back Allemandes of his other Country Dances; some choreographies even feature the instruction to waltz allemande with your partner (e.g. the 1815 The Chaplet) and Waltz double Alleme (e.g. the 1815 Duke of Sussex's Waltz); it's unclear exactly what Wilson meant by these instructions.

All of which means that there is no single Allemande figure to be used in historical Country Dancing. We can instead speak of trends, perhaps referring to the probability of a particular style of Allemande being used at a particular date. It's likely that the Wilsonian style was prevalent in the early 19th century but a broader repertoire of Allemandes was in use in the preceding decades.

Figure 5. The Allemande in Wilson's Quadrille and Cotillion Panorama, c.1818

Quadrille Dancing

The four couple Quadrille dance gained popularity in England in the late 1810s. Wilson

described two figures for use in Quadrilles, his Quadrille Allemande and the Pirouette Allemande . As we've seen, both of these

figures have their origin in the Cotillion dances of the 1770s.

The anonymous author of the 1818 Maître a Danser, a guide to Quadrille dancing, described a figure named Passe d'Allemande. This figure is effectively the Pirouette Allemande, but an important additional detail is added: Passe d'Allemande; there are a great many of them - The Allemande being a kind of dance which consists only in what is called 'Passe', but the most generally performed in Quadrilles is the above-mentioned. . This perhaps hints that earlier French origin Quadrilles were more likely to feature the Pirouette Allemande and later English Quadrilles the Quadrille Allemade ; other Allemande variations may of course have been introduced.

One especially popular Quadrille of 1816 was named Les Graces. It was included in Sets published by both James Paine and Edward Payne, also an 1817 Set by John Duval. It included a distinctive figure referred to in some sources as an Allemande that's depicted in caricature here. This allemande was an over-the-head pirouette involving three dancers.

Quadrilles of the 1830s may have introduced yet more meanings to the word Allemande . For example, the 1834

Quadrille Allemande published in New York by Thomas Birch20

makes use of Waltz turns, perhaps as previously seen in the Waltz Country Dances of Thomas Wilson.

Our Policy for

Allemande Figures

We here at

RegencyDances.org generally avoid specifying the specific type of Allemande to

use in a dance. We instead write “Allemande turn” or

“Allemande turn Right and Left”. Most of our Allemande figures

are animated as Crossed Allemandes , but you're welcome to interpret

them in other ways. It's quite possible that dancers two hundred years ago would have been uncertain about the Allemande figure too;

the same dance may have been performed in different ways from one

town to the next or from one year to the next.

Finally, if

you're reading this and know about some clues that we've missed,

please do get in touch. We'd love for further evidence to be found!

References

1. Gallini, c.1772, A New Collection of 44 Cotillons

2. Fishar, c.1773, Sixteen Cotillons, Sixteen Minuets, Twelve Allemands and Twelve Hornpipes

3. Wilson?, c.1830, The

Fashionable Quadrille Preceptor

4. Wilson, 1808, An

Analysis of Country Dancing

5. Wilson, c.1818, The

Quadrille and Cotillion Panorama

6. Saltator, 1807, quoted by Ralph Page in The History of Square Dancing

7. Guillaume, 1770, Almanach

dansant, ou positions et attitudes de l'allemande, avec un discours

préliminaire sur l'origine et l'utilité de la danse

8. Caldwell, 1772, The

Allemande Dance

9. Gallini, c.1772, Allemande

Cotillion

10. Cruickshank, 1797, The Allemande

11. De La Cuisse, 1762, Le

répertoire des bals

12. Longman, 1768 Allemande

Cotillon

13. Skillern & Straight, 1769, The Scotch Lilt

14. Skillern & Straight, 1775, Bevis

Mount

15. A.D. 1764 Country-Dancing

made Plain and Easy

16. Wilson, c.1816, Complete

System of English Country Dancing

17. Wilson, c.1818, The Quadrille and Cotillion Panorama

18. Cahusac, 1802, Duke

of Kent's Waltz

19. Wilson, 1818, Le Sylphe

20. Birch, 1834, The Quadrille Allemande

|

Figure 1. The Baroque Allemande Dance, Caldwell 1772. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Figure 1. The Baroque Allemande Dance, Caldwell 1772. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.