| Return to Index | ||||||||||||

|

Paper 3 Wilson's QuadrillesContributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 10th January 2014, Last Changed - 2nd February 2023]I recently animated three Quadrille Sets from Thomas Wilson's c.1817 second edition of the Companion to the Ball Room1 (see Figure 1). I thought it might be interesting to discuss those Quadrilles here, and to review the evolution of the Quadrille as a dance form during the Regency era.  Figure 1. Frontispiece and title page for Wilson's c.1820 fourth edition of the Companion to the Ball Room

Figure 1. Frontispiece and title page for Wilson's c.1820 fourth edition of the Companion to the Ball Room

Quadrilles became very fashionable in London in the second half of the 1810s. They usually involve eight dancers in a square formation, much like the earlier Cotillion dances. Figures 6 and 7 show examples of Quadrilles being danced. Quadrilles were generally arranged in groups of four to six separate dances, collectively referred to as a Set. Examples of popular Quadrille Sets include Paine's First Set and The Lancers. Hundreds of Quadrille Sets were published in England in the 1820s (though often as music without dance figures), in this article we'll investigate some of the earliest, particularly the Quadrilles of Thomas Wilson. Before going further, I'd like to acknowledge that my research on this subject has been heavily influenced by two key books. First there's Ellis Rogers' wonderful The Quadrille2, then Dr. John Gardiner-Garden's Historic Dance series, especially volumes 63 and 74. My research and conclusions (and errors!) are my own, but these works investigate the subject in far more detail. If you're interested in the historicity of dancing during the Regency era, they're essential reading.

The Form of the QuadrilleQuadrille dancing evolved out of the popular four-couple Cotillion dance form. Cotillions were published in England from the late 1760's, the Quadrilles emerged as their successors in London's ball rooms from the mid-1810s. The terminology for dancing could (and did) change over time; a Cotillion of the 1770s could be quite different to a Cotillion of the 1800s, a Quadrille of the 1780s could be different to one of the 1810s. There is, therefore, a risk of over simplification when discussing these dances. We'll only discuss the major characteristics of the dances here, we have further research papers that can offer a more nuanced understanding of the shifting landscape of social dance. Cotillions and Quadrilles share much in common, including their French origins, but there are important differences to their most typical arrangement:

Many French Quadrilles were danced by just two couples. Figure 2 shows an example of a two-couple Quadrille figure5. The requirement for fewer dancers may have been one reason for the Quadrille's early popularity. In 1786 the London based dance master S. J. Gardiner wrote that Quadrilles English Quadrilles of the Regency era were usually danced by eight dancers but most can be danced with just four. By the 1820s English quadrilles might be danced by twelve or even sixteen dancers7. Thomas Wilson even published sets of

The couple at the head of a Quadrille is referred to as the 1st Couple, they lead the first iteration of the dance. The 2nd couple to lead is the couple opposite the 1st Couple, then the couple to the right of the 1st Couple, finally the couple to the left of the 1st Couple. For most quadrilles the music would be played through four times to allow each couple a chance to lead the dance in turn. Some Quadrilles are arranged so that the 1st and 2nd couple dance the same figures at the same time; in which case the music is only played through twice, once for the

The French Dancing Master Landrin published groups of Cotillion dances arranged in Sets from around the year 1760. A collection of 10 such

The First Set

An anonymous story published in 182910 claimed that a lady of celebrity held a Parisian Fête on the 16th August, 1797 in which

Figure 3 is an 1821 illustration of the La Trenis dance from the First Set14. I don't know whether the Hullin creation myth is accurate but it was endorsed by the Lowe family in the 1831 third edition of their Ball-Conductor and Assembly Guide (and presumably also in the 1822 second edition). I've also found the First Set of Quadrilles arranged as Cotillions in a 1786 collection published in London (see, for example Les Pantalons), and a close approximation in Michael Kelly's c.1804 Eight French Country Dances, their origin is clearly more nuanced than the Hullin claim would have us believe. Regardless of their origins, these Quadrille dances eventually became so popular in England that Thomas Wilson in 1824 complained that most dancers only knew the figures for the

The English dancing master who claimed to have introduced the Quadrille to London was Edward Payne. Payne's First Set of Quadrilles were published c.1815 (perhaps early in 1816), they preserved the French figures for the dances. Payne went on to publish 11 sets of Quadrilles before his death in 1819. One early commentator on Payne was the Scottish dancing master Barclay Dun. Dun's 1818 A Translation of Nine of the Most Fashionable Quadrilles16 recorded that Payne

Another early promoter of the First Set was James Paine. Paine was an orchestra leader at Almack's Assembly Rooms in London. Paine's First Set of Quadrilles were published in 1816 17, they reused the figures of Payne's First Set but added an extra Quadrille named La Pastorale. Paine went on to publish 17 sets of Quadrilles by 1821. The obvious potential for confusion between the names

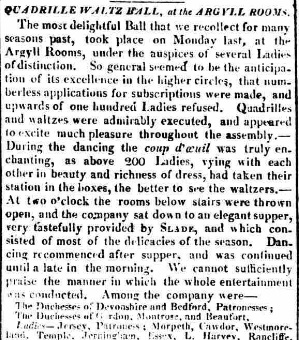

The First Set were catapulted to prominence in London, and elsewhere in Britain, after having been danced at the 1816 Carlton House Ball. We've written of this important event elsewhere, you might like to follow the link to read more. The First Set, as published from 1816, are often claimed to be the very first Quadrilles danced in London, that's unlikely as Quadrilles were being danced at fashionable venues from at least as early as 1811. The Morning Post newspaper for June 13th 1811 contains a glowing report of a Quadrille Waltz Ball held at the Argyll Rooms, and hosted by the Duchess of Devonshire and other

Captain Gronow, in his memoirs, recalled the introduction of the First Set to Almack's:

By the early 19th Century the Quadrille had evolved into a four couple dance. Thomas Wilson wrote in the 1822 second edition of his Quadrille and Cotillion Panorama that  Figure 4. Report of a Quadrille and Waltz Ball, 1811.

Figure 4. Report of a Quadrille and Waltz Ball, 1811. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk). We know the First Set was very popular in Regency London. So much so that many subsequent Quadrille Sets either omitted dance notation (the figures of the First Set were implied), or they supplied notation but could substitute the First Set figures. One clue to the importance of the First Set is the existence of aide-mémoire Fans decorated with Quadrille instructions. A superb example tentatively dated to 1816 (I'd date it to 1820 or later) can be seen in the Ventagli collection21.

Chronology of Wilson's QuadrillesThomas Wilson was a London based Dance Master, he published at least ten Quadrille Sets of his own invention, not including his Quadrille Country Dances or his Waltz Quadrilles. There are four sets of Quadrilles in his 1817 Quadrille Instructor22, three in the 1817 second edition of the Companion to the Ball Room1, and three more in the 1824 Danciad23; he was also credited with the Quadrille Set in the c.1816 No 31 of Button, Whitaker & Compy's Selection of Dances, Reels & Waltzes. He was further credited with publishing instructions for popular Quadrilles by other choreographers in The Complete English Quadrille Preceptor for 1823 (which was expanded further in 1830, though his authorship of these works is doubted), in La Batteuse and Le Moulinet &c. in 1817, and in the Danciad. As can be seen from the dates, Wilson was active in teaching Quadrilles from almost the moment they became popular in London.

I don't know if Wilson's published Quadrilles were ever danced at society Balls, they would certainly have been used within his own dance academy24, an advert for which can be seen in Figure 5. The cover of the 1817 second edition of the Quadrille Instructor claimed that they are used In 1817 Button & Whitaker published a collection of Quadrilles called Button, Whitaker, and Co's Miniature Edition of Payne's and Wilson's Quadrille Figures, in French and English25. It contained 50 quadrilles, presumably 10 sets of 5; this may be independent evidence of Wilson's Quadrilles being danced socially; dancers would find such cards convenient as an aide-memoire when attending a Ball. However, Wilson regularly published through Button & Whitaker, so I suspect it's a work that he himself sponsored. Before investigating the dances, it's perhaps worth reflecting on the chronology of these works. Wilson didn't date either the Quadrille Instructor, or the Companion to the Ball Room. I've had to do a little research to provide reasonably plausible dates. The main challenge is that multiple editions of each work exist; I don't have access to each edition, so I can't easily determine whether the Quadrilles date to the first editions, or to later editions; here's what I've discovered: The May 1817 New Monthly Magazine26 records the publication of theSecond Edition, greatly improved of 'The Quadrille Instructor'. They had previously reviewed the first edition in February 1817. The differences were the 10 new diagrams, and the 15 new tunes and figures. This suggests that one of those Quadrille sets dates nearer to 1816, and three to 1817. The edition I have access to is the second edition22. The Gentleman's Magazine in 1816 records the publication of the first edition of the Companion to the Ball Room27. At this date the book is 232 pages long, and neither its title page nor review mention the inclusion of any Quadrilles. A similar 1816 review in the Repository of Arts28 also fails to mention any Quadrilles. It appears that there were no Quadrilles in the first edition; this is confirmed by a footnote in the fourth edition that apologises for the lack of Quadrilles in the index of the 1817 second edition:The Sudden popularity of Quadrilles made necessary for the Author, in publishing the second Edition, to use the Letter-Press printed for the first, which was the reason they were not inserted in the Index. The edition I have access to is the 257 page long fourth edition1 - I've not been able to date it, but someone wrote the date 1820 on the title page (see Figure 1). This date seems plausible, it certainly dates no earlier than 1818 as it quotes a review from December 1817. The third edition was also published in 181729, so I've assumed it must be the fourth edition.

The significant expansion of the second edition of The Quadrille Instructor, and the inclusion of new Quadrille dances in the second edition of the Companion to the Ball Room, are evidence of the Further evidence of the Quadrille's new found popularity can be seen in the caricatures and prints published around this time, including the images in Figure 6 30 and Figure 7 31, both of which date to 1817. These images show French Dancing Masters teaching Quadrilles in private London homes; Wilson had a significant teaching business, it's tempting to imagine him into the pictures (and affecting a French accent)! It's notable that the first 'Department' of dancing mentioned in his c.1820 advert (see Figure 5) was the Quadrille.

Figure 6. Practising the La Poule Quadrille at home, 1817. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Figure 6. Practising the La Poule Quadrille at home, 1817. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Content of Wilson's Quadrilles

The Quadrilles I've studied most closely are those I've animated from the Companion to the Ball Room and the Quadrille Instructor. Each Quadrille Set is made up of 5 dances, for a total of 35 separate Quadrilles. Unfortunately Wilson didn't use a simple naming convention, so I've had to apply my own. I've called the first (and earliest) unnamed Set in the Quadrille Instructor Wilson's 1816 Set. Wilson numbered the remaining Quadrille Sets from 1 to 3, and did the same thing in the Companion to the Ball Room. I've called them Wilson's First Set, Wilson's Second Set and Wilson's Third Set, and suffixed them with

The first dance from I'm unsure of the provenance of the tunes for the Quadrilles. If any reader is able to shed light on the subject, then please do get in touch. I'd like to know if Wilson wrote/commissioned the music himself, or whether he 'borrowed' established tunes from somewhere else. In the introduction to the Quadrille Instructor Wilson emphasised that most other Quadrilles published in England had little musical merit and wereincompatible with modern taste, implying that he was particularly proud of his music.

You may be able to see in Figure 8 that La Coquette is subtitled La Pantalon. Wilson provided dance figures for this Quadrille, but he designed it so that the figures from the Pantalon quadrille of the First Set could be used instead. This is made explicit in the Preface to the Quadrille Instructor, where we are told: The Quadrille Instructor is a particularly helpful work for anyone seeking to interpret Quadrilles. Wilson provides the music, an indication of which strain to use for each dancing figure, a diagram and description of each figure, and specific stepping instructions. Most of the figures in the Quadrilles employ only four dancers at a time; the dance has to be repeated to allow the other couples to have a turn. This follows the convention from the First Set, and emphasises the early heritage of the Quadrille as a two couple dance. The figures used in many of the Quadrilles are simple, perhaps indicating that they are used to teach novices. They're often composed of turns, promenades, chasse movements and chains; figures that are easily learned. The Quadrilles do include some unusual figures, such as the Pousette and the Transverse Lines, with detailed instructions to explain them.  Figure 7. Quadrilles: practising the La Trenis Quadrille for fear of accidents!, 1817. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Figure 7. Quadrilles: practising the La Trenis Quadrille for fear of accidents!, 1817. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Each Quadrille Set ends with a Finale dance. This involves all of the dancers, and marks the end of the Quadrille. Wilson explained this further in the Quadrille and Cotillion Panorama: Wilson's Quadrilles were published at an important transitional time when the Quadrille was rapidly gaining popularity in England. As such, they're a fascinating insight into the era. Here are the individual dances (with alternative figures from the First Set in parentheses):

Many of the Quadrilles are designed to be compatible with the figures from the First Set, though some aren't. Wilson included two L'Ete dances in his

A further anomaly is that Wilson didn't provide a Finale for his

The Triumph of the QuadrilleQuadrille dances gained popularity incredibly quickly. So much so that within a few short years they had almost completely displaced the English Country Dance from England's fashionable Ball Rooms. There were relatively few new Country Dances published in England in the 1820s compared to previous decades, but hundreds of Quadrille Sets. Wilson did his part to ensure their success. The poet Thomas Moore, writing under his pseudonym of Thomas Brown, the Younger wrote an 1823 poem called Country Dance and Quadrille34 (see Figure 9); this poem beautifully describes the changes to the Ball Room of his day. In his poem, the anthropomorphic 'Mamselle Quadrille' reigns in London, the 'Nymph' of the Country Dance is relegated to a provincial town. The Country Dance experiences one last victory before the Quadrille takes over entirely.

ONE night the nymph call'd COUNTRY-DANCE,--

References1. Wilson, c.1816, Companion to the Ball Room 2. Rogers, 2008, The Quadrille, 4th Edition 3. Gardiner-Garden, 2013, Historic Dance, Volume VI 4. Gardiner-Garden, 2013, Historic Dance, Volume VII 5. Marque, 1821, Étrennes à Terpsichore (page 14) 6. Gardiner, 1786, A Definition of Minuet-Dancing 7. Wilson, 1824, The Danciad 8. Wilson, c.1830, The Fashionable Quadrille Preceptor 9. Landrin, c.1760, Potpourri françois des contre-danse ancienne 10. Anonymous, 1829, The Young Lady's Book 11. Hullin, 1798, 2eme Receuil Des Nouvelle Contre-damse 12. VauxhallGardens.com, Performers at Vauxhall Gardens, 1661-1859 13. Smith, 1831, Festivals, Games, and Amusements 14. Marque, 1821, Étrennes à Terpsichore (page 28) 15. Wilson, 1824, The Danciad 16. Dun, 1818, A Translation of Nine of the Most Fashionable Quadrilles 17. The Morning Post, London, Aug 13, 1816: New Music 18. The Morning Post, London, Jun 13, 1811: Fashionable World 19. Gronow, 1862, Reminiscences of Captain Gronow 20. Wilson, 1822, The Quadrille and Cotillion Panorama 21. Fan, c.1816, Hand written instructions for the First Set 22. Wilson, 1817, Quadrille Instructor 23. Wilson, 1820 (volume 1) & 1824 (volume 2), Danciad 24. Wilson, c.1820 Wilson's advert, from The Companion to the Ball Room, fourth edition 25. Ackermann, 1817 The Repository of Arts 26. Anonymous, 1817, New Monthly Magazine 27. Anonymous, 1816, The Gentleman's Magazine 28. Ackermann, 1816, The Repository of Arts 29. Reeve et. al., 1817, The Literary Gazette 30. Sidebotham, 1817, Quadrilles - practising at home 31. Cruikshank, 1817, Quadrilles - practising for fear of accidents! 32. Wilson, c.1820, La Coquette, from The Companion to the Ball Room, fourth edition 33. Wilson, 1822, The Quadrille and Cotillion Panorama 34. Moore, 1823, Country Dance and Quadrille

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved