| Return to Index |

|

Paper 5 The Life of Thomas Wilson, Dancing Master (1774-1854)Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 12th May 2014, Last Changed - 14th March 2025]If you've spent any time reading the pages here at RegencyDances.org you'll have noticed that we regularly quote from the works of Thomas Wilson. Wilson is incredibly important to anyone who researches Regency era dancing, he wrote most of the books that we rely upon but very little is known about the man himself. I'm hoping to address that deficiency in this article.  Figure 1. Waltzing - vide Wilson's Rooms, 1817. (left) Image courtesy of the British Museum. Wilson as Mother Growse, 1807 (right). Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 1. Waltzing - vide Wilson's Rooms, 1817. (left) Image courtesy of the British Museum. Wilson as Mother Growse, 1807 (right). Image courtesy of the British Museum.

A complete (or as complete as is possible) list of Wilsonian publications is available here. Wilson wasn't particularly famous in his own day but he was successful in his chosen profession. It's surprisingly difficult to find any biographical details about his early life beyond those hinted at within his own books. We know that he was associated with the King's Theatre Opera House (also known as London's Italian Opera House), we know that he hosted Balls, taught dancing and wrote a prodigious number of books. But what else is known?

Several portraits of Wilson have existed but so far they've eluded my attempts at discovery. Wilson mentioned in his 1811 Supplement to the Treasures of Terpsichore that the first edition of his 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore included a

Wilson in Liverpool?

In the 1885 reprint of an 1852 book named Liverpool, a Few Years Since by An Old Stager there's a curious passage recounting a local character who lived in Liverpool Close to St. Anne’s Church was the house of a celebrated character amongst us, both then and long afterwards. We speak of Mr. Thomas Wilson, profanely called Tommy Wilson, the dancing-master, by his wicked pupils. A good fellow was Tommy, although a strict disciplinarian in “teaching the young idea,” not “how to shoot,” but how to turn out its toes and go through the positions. But, unfortunately, Mr. Wilson grew too ambitious, and, instead of contenting himself with fiddling for boys and girls to dance to, would preside over orchestras and concerts, and cater for the amusement of the public, by which we fear he did not grow too rich. He was a worthy, warm-hearted man in his way, and somewhat of an original, and withal possessing the good opinion of all who knew him.3

Could this

A similar retrospective named Recollections of Old Liverpool by J.F. Hughes in 1863 recorded that a Wilson included a passing reference to Liverpool in his Danciad. He wrote that a fancy dress ball was held in Liverpoolwas bred to a mechanical business, which, before the expiration of his apprenticeship, he was compelled (with others) to relinquish, (that being entirely ruined through certain financial speculations of Mr. Pitt). Having some taste for dancing, as an amusement, he determined to endeavour to qualify himself so as to follow it, as a profession, and which was only effected after long and unremitting exertions, such as few individuals would encounter. some years ago... of the most magnificent description, at which all the families of rank within the surrounding distance of many miles were present. For variety of character and original costume, this splendid Ball has never been surpassed.. It may be a reference to a Ball that he (or perhaps a close family member) facilitated - he rarely praised Balls hosted by anyone else! It's odd anecdote to find within his work and adds weight to the idea that he himself, or perhaps a family member, had a connection with Liverpool.

In one of his later publications, the 1821 The Address, Wilson revealed that he had been a professional

Wilson in DunstableWilson was born in the town of Dunstable in Bedfordshire on the 25th February 1774. At least, that's what he asserted in an 1851 declaration to The Royal Literary Fund (which we'll return to later). An 1845 article in The Gentleman's Magazine by J.D. Parry provides some further biographical information; in an article about Dunstable we're informed: there is now in London another respectable and kind-hearted septuagenarian "artist" in his way, and of copious historical and antiquarian lore to boot, who has celebrated his native place in one or two of his poetical "placards" which everybody has seen, whom the writer knew, with his most beautiful and innocent assistant, Miss Margaret M___, 15 years ago, being no less renowned a personage than "Dancing Master Wilson."5

This brief passage reveals quite a lot. We learn that Wilson lived into his 70s, he considered Dunstable to be his

Wilson's Wilson's Family LifeI'm indebted to Philippa Robertson for contacting me with much of the following information regarding Wilson's private family life. Philippa had been investigating the life of her great aunt Sophia Wilson using private documents from her family archive. Sophia was found to have been married to a dancing master named Thomas Wilson who was born in Dunstable, he is indeed our Thomas Wilson. We've therefore relied on her information in the following section.

Wilson was married to the 23 year old Sophia Bromley at St Margaret's Church in Westminster in 1807. She is known to have assisted at Wilson's academy from at least as early as 1808 when he advertised that

It transpires that Sophia and Wilson were separated. The explanation for this separation is unknown but at some date she moved in with her sister Mary Randal. She went on to advertise dance tuition under the name Mrs Wilson in the 1830s; in one such advertisement (Morning Post, 24th November 1836) she described herself as The mystery of why they separated remains unsolved. It's perhaps notable that the balls Wilson advertised after 1815 usually commenced with a couple dance involving both himself and a favoured pupil, Wilson and Sophia may have been estranged from around that 1815 date.

Wilson's Dance Academy

At some point Wilson opened a London Dance Academy at

In January 1811 Wilson wrote: Figure 2 shows the price list at Wilson's Academy in 180810. A similar price list exists for 181111. Most of the prices were unchanged over those 3 years but a few increased; they are the Scotch Minuet, the Allemande, the Ground Hornpipe, the Louvre & the Corsair Hornpipe. Wilson taught many different types of dance; there are social dances, stage dances, courtly dances and international dances within his repertoire. He intended the public to believe that he was a master of his trade.

At some point Wilson's Academy moved to

An 1822 advert in the New Times newspaper (6th March, 1822, with thanks to Alan Taylor for the discovery) indicates that Wilson was running four separate academies at that date. His Wilson published a review of his impressive successes to date in 1822 (Bell's Life in London and Sporting Chronicle 24th March 1822): Mr Wilson, Teacher of Dancing, though so well known to the Public, still feels the necessity of an Advertisement, in hopes of increasing his Pupils, and improving his finances; for although he has had Eighty-six Public BALLS, danced at Twenty-four different Theatres (including Five years at the Opera House) taught almost innumerable Ladies and Gentlemen and Children, having qualified upwards of Thirty persons to become Professors, besides occasionally giving instructions to nearly One Hundred more, having Ten Professional Apprentices, and written more than Ten works on Dancing, besides several Dramatic pieces; having also invented Six new species of Dancing, having now open Four Academies for Dancing, at different parts of the town, which he superintends personally, and where he continues occasionally to teach in Twenty-five different departments of the Art; he has yet his fortune to make; but as he still hopes of keeping his carriage (so requisite to professional eminence) he is determined, in order to facilitate so desirable an object, to be always at home, to give lessons privately (if required) at any time, at his residence Old Bailey; or at his Western, Central or Northern Academies; he considers it only candid towards other Professional persons in general, to say that he cannot engage, like some Teachers, completely to qualify any one for the Ball Room in only a few Lessons; nor can he boast of the lowest prices.

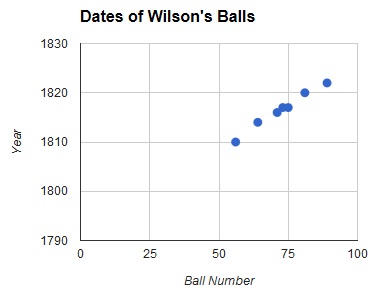

Wilson increasingly turned to poetry in order to advertise his services in the 1820s. An example from 1828 (Morning Chronicle, 8th September 1828) follows:  Figure 4. Dates of Wilson's Balls

Figure 4. Dates of Wilson's Balls

A later 1832 advert mentioned a new repertoire of dances including the Waltz Cotillion and Whigs, Tories, and Radicals. - The forthcoming meeting of Parliament, the present political state of the British empire, and the great excitement amongst the various parties, make it self-evident that new steps must be instantly taken to guide the vessel of State. Consequently, DANCING MASTER WILSON, of 18 Kirby-street, Hatton-garden, a well-known Inventor of New Steps, takes this opportunity of informing his Majesty's Ministers, the Bishops, Knights of St. Stephen's, and others, that he has a large assortment of New Steps and Figures, adapted to Whig, Tory, and Radical interest. Amongst others, he has some Cheering Capers for the Radicals, Consoling Steps for the Whigs, and some thorough-paced Movements for the Tories, that require no pledges, together with a new version of the well-known dance called Ratting, in which the performers may change sides witheclat.

Wilson's Public BallsWilson claimed to have hosted at least 89 Public Balls by 1822, I've found datable evidence for seven of them. His 56th was in 181018, the 64th in 181419, 71st in 181620, 73rd in 181713 (see figure 3), 75th also in 181721, 81st in 182022, and 89th in 18227. I've plotted them on a graph in Figure 4; if we extend that graph backwards, then it's likely that he started hosting Balls around 1790, when he was approximately 20. If my assumptions about the date of his Holborn Academy are correct, then this is before the Academy opened. It's possible that Wilson was being disingenuous and that he didn't start counting at zero. He himself warns us in his 1824 Danciad that some dance masters began numbering their Balls from 20!23 Addenda: I've dated some more of Wilson's Balls using newspaper references: his 61st and 62nd Balls were held in 1813, his 63rd and 65th Balls were in 1814, his 66th, 67th and 70th in 1815, his 74th in 1817, his 76th, 77th and 78th in 1818, his 79th in 1819, his 82nd in 1821, and both his 86th and 87th were held in 1822. Wilson was careful to feature fashionable dances at his Balls. His 1814 Ball introduced the increasingly popular Waltz and the 1817 Balls featured the Quadrille in their titles (see Figure 3); they weren't advertised for his 1816 or earlier Balls. The 1814 Ball was hosted at the Crown and Anchor Tavern. This venue may sound a little basic but its Grand Ballroom as depicted in Figure 5 suggests otherwise24. The Crown and Anchor Tavern was one of the larger venues in London that was available for hire, Wilson routinely used the venue for his Public Balls throughout the 1810s. We've written more about Wilson's balls held at the Crown & Anchor Tavern in another paper. It's worth reflecting on who attended Wilson's Public Balls. I've only found one brief first-hand account from an attendee who wrote in 1822 (Bell's Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, 21st April 1822): We know that Wilson advertised in newspapers and magazines, I therefore suspect that his clients were often from the wealthy middle classes. Perhaps the daughters of prosperous tradesmen. The 1817 advertisement in Figure 3 is especially interesting; we learn that Wilson's Ball featured the most fashionable dance styles known from Almacks and elsewhere, also that stewards would keep out anyLast week on the same evening, after looking in at Almack's, we joined a party, by appointment, at Wilson's Fancy Dance Ball; both were crowded by the gay and affluent votaries of fashion; and Quadrilles were predominant. At the latter place we particularly noticed some interesting new Quadrilles and fancy dances, which detained us there till we were obliged to retire. improper company. One fascinating detail is that it was to open with a Minuet Waltzdisplay dance involving Wilson and a young pupil (caricatured in Figure 1 perhaps?). The Minuet had largely fallen from favour by the mid 1810s; Wilson promoted himself as an elite dancer (of the King's Theatre), an elegant and modernised Minuet would be an effective way to introduce the evening and himself as the master of ceremonies.

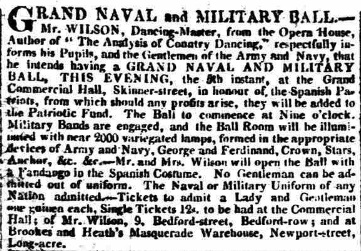

Some of Wilson's Balls had special themes. The Morning Post for January 5th 1809 contains an advert for Wilson's Grand Naval and Military Ball25 (see Figure 6)

The same newspaper for December 29th 1815 contains an advert declaring Wilson's First Winter Ball in 181626. It also reports that he had

An advert in The Morning Chronicle (11th January, 1821) described Wilson's 82nd Ball as a Christmas Ball, and Twelfth Night Entertainment. It promised to feature:

Further Wilsonian Balls were held throughout the 1830s. An advert in The Morning Post for 8th April 1835 reports

In 1844 Wilson advertised his

Figure 6. Advert for Wilson's 1809 Grand Naval and Military Ball.

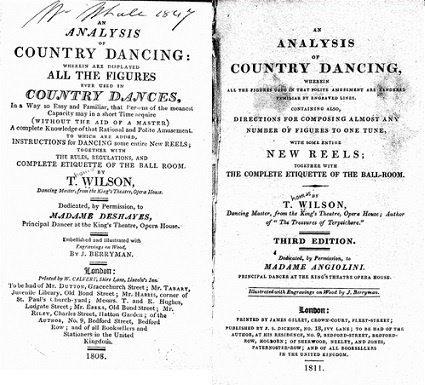

Figure 6. Advert for Wilson's 1809 Grand Naval and Military Ball.Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk) Wilson's PublicationsThere is evidence for around fifty Wilsonian publications issued in the years between 1808 and 1830, most related to dancing, several running to multiple editions. We've written another paper on Wilson's books so we'll not investigate them in detail here. His first major publication was the 1808 An Analysis of Country Dancing28. This work was dedicated to Madame Deshayes, a principal dancer at the King's Theatre Opera House (see Figure 7). It sought to catalogue and explain all of the figures used in English Country Dancing at that date. It was published through the financial assistance of a list of subscribers and sold out within 3 years. A second edition was published in 181129, this also appears to have sold out immediately. A third edition was also published in 181130 (see Figure 7); it had a print run of 2000 copies and had sold out by 181431. Wilson's influence and fame must have been growing during this time. A curiosity in the third edition is that the dedication changes to Madame Angiolini, another principal dancer at the King's Theatre Opera House; perhaps this was under the influence of his wife Sophia who had studied under Angiolini. He also changed publishers between the first and third editions moving from W. Calvert to James Gillet. He worked with at least 6 different publishers throughout his career. The list of subscribers for three of Wilson's works are known: the 1808 Analysis of Country Dancing32, the 1811 Supplement to the Treasures of Terpsichore33, and the 1816 Description of the Correct Method of Waltzing34. There are a few subscribers that appear in more than one of these lists, most notably a Mr. Thomas who prepaid for 6 copies of 'Analysis', and 6 of 'Terpsichore'. A valuable customer (and perhaps the owner of a book or music shop). Wilson was kept busy in the second half of the 1810s. He published approximately 15 new titles between 1815 and 1820, not including subsequent editions of earlier works. He had been working on a major update of the Analysis of Country Dancing since at least 181631 but publication was regularly delayed by more urgent projects (he announced it multiple times in 181635 and again in 181936 with double the number of engravings). He eventually released this Magnus Opus in a completed form as The Complete System of English Country Dancing in 182037. It could be argued that this work came to market too late, interest in Country Dancing having significantly fallen across the industry by 1820; his works on Waltzing and Quadrilles were more timely.

It's not clear how much Wilson made from his publishing, he reported in a footnote to the 1816 Companion to the Ball Room that  Figure 7. Title pages to the First and Third editions of An Analysis of Country Dancing

Figure 7. Title pages to the First and Third editions of An Analysis of Country Dancing

The author has, on dancing, published more39

Wilson published many other works the last of which appears to have been the 1852 The Art of Dancing. He also produced

Wilson and the King's TheatreThe one widely known biographic detail of Wilson's life is that he was a Dancing Master from the King's Theatre Opera House (see Figure 9 for an image of the Theatre40). He proudly announced this on the cover of many of his books and it's repeated in the contemporaneous reviews of his work. I've not found any corroborating evidence to describe his involvement there, I suspect his role was quite minor. The King's Theatre was also referred to as The Italian Opera House in many sources, the two names refer to the same institution.

Wilson declared his association with the King's Theatre in 'Analysis' in 1808, and continued to do so through to the 'Danciad' in 1824. Yet throughout he used the phrase

Could he have been invited to London from Liverpool to train as a dancer at the Opera House c.1800, perhaps under the influence of John Braham? I can't say, but it makes for a good story. The timeline suggests that he left c.1806 to start his own Academy. The only independent reference to a Wilson performed in a production that he staged himself at the Lyceum Theatre in late 1807. His advertisement in the Morning Advertiser for the 14th of December 1807 declared that

A peculiar apology printed in the Morning Advertiser for the 13th January 1809 confirms that Wilson had left the King's Theatre by that date; the apology reads:

Whatever his role at the Theatre had been he retained some access to the dancers. He dedicated several of his books to them and listed them as subscribers. There was another Dancing Master known to have worked at the King's Theatre in the late 1810s, a certain G.M.S. Chivers. Wilson is particularly scathing about Chivers in the 'Danciad', suggesting a personal animosity41. Could Chivers have replaced Wilson at some point? Another teacher, Mr. Cunningham, advertised his dancing services in 1818, also with the phrase

Wilson's Later Life

In later life Wilson became colloquially known as Dancing Master Wilson, an eccentric character of some renown. He continued to host Balls and complained of hardship, it seems he was somewhat successful however. A peculiar reference to Wilson was published in a newspaper called The Odd Fellow in 1841 (1st May 1841) in a column that satirised the profession of dancing masters; the column described a generic grubbing dancing master who struggled to make a living, and then referenced how this (presumably fictional) caricature felt about Wilson:

Wilson continued to teach dancing, host balls, write poetry, and entertain his friends throughout the 1840s and into the 1850s. He was particularly associated with a London club named The Ancient and Honourable Lumber Troop, he'd acted as Master of Ceremonies for their gatherings from at least the late 1820s; an 1830 reference to the club described him as Comrade Wilson (Morning Advertiser, 8th July 1830)

Tragedy struck Wilson in or around the year 1851. He contracted cholera, the illness ended his teaching career. He submitted a request for support to the Royal Literary Fund in 1851 (the letter is preserved at the British Library). He wrote: It was in or around the year 1852 that Wilson's (presumably) final work was published, his The Art of Dancing. It seems probable that Wilson turned once again to publishing in the last months of his life; it's not his best work but it demonstrates that Wilson's insight remained relevant into the 1840s and beyond. His passing was announced in the Morning Advertiser newspaper for 15th March 1854; he was presumably 80 years old, though the obituary states he was 86. It reported: On Wednesday, the 8th instant, Mr. Wilson, of dancing notoriety, died in the Union Workhouse, West-street, Smithfield, (which he had entered but a fortnight before his death,) at the advanced age of 86. Seldom has it fallen to our lot to record the death of one, whose career was so chequered, whose eccentricities were so remarkable, and whose ruling passion for thelight fantastic toeand the muses, was indescribable within a short period of his mortality. Many will, doubtless remember that Mr. Wilson conducted his dancing avocation in the most sumptuous style. To everygrand ball(for such he designated it), large and full bills were printed, and one or more elegantly-executed engravings, accompanied them. Indeed, the number of such, and of his poetic effusions, would (if not known) be deemed incredible. Of his productions in prose, are six volumes on dancing; and in verse, nearly 100, all of which must have kept himpoor indeed.Among other places, he figured at the Italian Opera, and the Crown and Anchor Tavern, Strand. For many years Kirby-street, Hatton-garden, was the scene of his labours, which were greatly ramified. The burthen of his life was constantly relieved by the benevolence of Mr. Walter, of Shoe-lane, Licensed Victualler and Common Councilman; and Mr. Thomas Chapman, which latter gentleman in 1815, at the Drury lane Theatre, took a prominent part in a play, composed by our hero, who, with grace, alsofretted his hour on the stage,and it may be predicted, that we shallnever look upon his like again. A few years later Wilson was remembered in an essay by Henry William Bride on the history and antiquity of dancing (Galway Mercury, and Connaught Weekly Advertiser, 17th January 1857). Bride wrote: ... I remember a gentleman well known for his Terpsichorean abilities, which he often exhibited when publicly acting as Master of the Ceremonies at Vauxhall Gardens, near London, gratuitously, for some of the numerous charities of our far-famed Modern Babylon, whose large broadside sheets, redolent with rhymes (poetry!) in favour of what he denominatedThe Glorious Art of Dancing,often attracted the attention of the street passenger, and frequently excited his smiles on perusing the poetical endeavours of Dancing Master Wilson (such was the cognomen by which he was known, and by which he advertised himself,) to lure the public to become his pupils at his celebrated academy, near Temple Bar. I met him a few times at the private parties of some mutual friends, and a more amiable companion and a more pious and inoffensive character I do not believe ever was to be met with among those individuals who are compelled to procure their subsistence amid the gay and thoughtless votaries of worldly pleasures. He is, however, gone, I hope, to a happier and a better world; and there many individuals yet living in all parts of the British Empire who will not soon forget Dancing Master Wilson, of London notoriety.

Wilson's LegacyWilson is of great importance to modern dance historians, he documented the dancing styles of his day to a greater extent than any other contemporaneous writer. However, as a modern researcher it's possible to put too much emphasis on his work. He often complained in his books that other dancing masters got things wrong and that his style of dancing was the only correct system; this implies that other contemporaneous dancing masters were likely to have disagreed with some of Wilson's teaching. He included an advert in his 1821 The Address that listed the various dance forms that he claimed to have personally invented and shared with the world:The Quadrille Country Dancing, first introduced at his Waltz and Quadrille (being his 79th) Public Ball. He was proud of his achievements.

It's difficult to find any independent contemporaneous accounts that recognise Wilson as a dancing master of genuine influence, rather than a mere eccentric, but one 1817 review in La Belle Assemblée stands out. They wrote:

Anyway, that's it for now. The information we've located about Wilson is fragmentary; if anyone out there can fill in some of the gaps, do please get in touch as we'd love to know more.

References1. Wilson, 1811, Supplement to the Treasures of Terpsichore 2. Cruikshank, 1817, Waltzing-Vide Wilson's Rooms 3. An Old Stager, 1852, Liverpool, A Few Years Since 4. J. F. Hughes, 1863, Recollections of Old Liverpool 5. J. D. Parry, 1845, The Gentleman's Magazine 6. Leigh Hunt, 1834, London Journal, Dancing and Dancers 7. Wilson, 1824, Danciad 8. Wilson, 1808, Analysis of Country Dancing, first edition 9. Wilson, 1811, Supplement to the Treasures of Terpsichore 10. Wilson, 1808, Analysis of Country Dancing, first edition 11. Wilson, 1811, Analysis of Country Dancing, third edition 12. Ackermann, 1814, The Repository of Arts 13. Ackermann, 1817, The Repository of Arts 14. The London Morning Post, Oct 10, 1823, News 15. Scott & Taylor, 1829, The London Magazine 16. True Sun, Sep 24, 1832, News 17. The Sunday Herald, Apr 21, 1833, News 18. Wilson, 1811, Supplement to the Treasures of Terpsichore 19. Ackermann, 1814, The Repository of Arts 20. Harvard, Illustrated Ticket to a Ball (WorldCat Entry) 21. Ackermann, 1817, The Repository of Arts 22. McLeod, 2012, Wilson's advert quoted in Lesley-Anne McLeod's Blog 23. Wilson, 1824, Danciad 24. 1848, Illustrated London News 25. The Morning Post, London, Jan 05, 1809 News 26. The Morning Post, London, Dec 29, 1815 News 27. The Morning Post, London, Feb 12, 1816 News 28. Wilson, 1808, Analysis of Country Dancing, first edition 29. 1811, The European Magazine, and London Review 30. Wilson, 1811, Analysis of Country Dancing, third edition 31. Wilson, 1816, The Description on the Correct Method of Waltzing 32. Wilson, 1808, Analysis of Country Dancing, first edition 33. Wilson, 1811, Supplement to the Treasures of Terpsichore 34. Wilson, 1816, The Description on the Correct Method of Waltzing 35. 1816, The New Monthly Magazine, and Universal Register 36. Nichols, 1819, The Gentleman's Magazine 37. Wilson, c.1820, The Complete System of English Country Dancing 38. Wilson, 1816, The Companion to the Ball Room 39. Wilson, 1824, The Danciad 40. 1843, Interior of the King's Theatre (then known as Her Majesty's Theatre) 41. Wilson, 1824, The Danciad 42. La Belle Assemblée, 1817 Varieties Critical, Literary, and Historical

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved