| Return to Index |

|

Paper 12 Evening Dress, Ball Dress and Court Dress in the Napoleonic eraContributed by Heather Constance, of Hampshire Regency Dancers and The Napoleonic Association |

I have been attending Regency balls for a number of years now, and something that has particularly struck me is the number of ladies who turn up in dresses unsuitable for dancing in, because they are too long, or have a long train, with the result that they cant dance properly because they are trying to hold it up all the time, or someone else treads on it, with unfortunate results. With a number of commemorative Duchess of Richmonds Balls coming up, I thought I would offer a few pointers.

The one thing to remember is that the fashion etiquette of the time dictated what you wore for a particular occasion. There were three types of dress worn in the evening: evening dress, for dinner or an informal social occasion, distinct from morning dress which one wore around the house during the day; ball dress, for going to a dance; and full dress, the most formal type of dress for a really formal dinner, concert, reception or the opera.

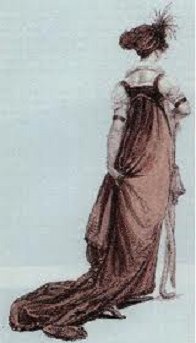

Full dress might well also include some feathers with an elaborate evening cap (but not tall upstanding feathers), or a parure (matching set) of tiara, necklace, bracelets and earrings. Trained over-robes might well be worn, with long gloves and a trailing shawl to complete the outfit. Evening dress might be a less elaborate version, say for a dinner party, or simply exchanging a cotton morning dress with a filled in neck line for a silk dress with a low neckline and an attractive necklace sleeves long or short to suit the wearers age and taste.

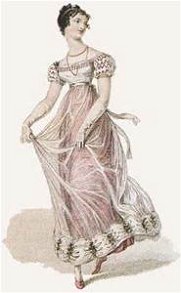

A ball dress was designed to dance in, and by 1815 a fashionable ball dress had decorations and flounces at the hem, which was worn well clear of the floor to show the feet and thus allow the dancer to show off her dance steps (or at least not to trip over her hem!) Remember that most ladies who danced were below the age of 25 (dont worry, it doesnt apply today!) An older lady might well wear full evening dress with a trained skirt to a ball, but she would show by this that she was a chaperone and had no intention of dancing.

I have noticed that some ladies in the re-enactment societies wear dresses of a very directoire, very French style, which is, after all, understandable if they belong to a French regiment. This is actually quite an early style, from the 1790s, and was a slightly more extreme form of the soft muslin gowns fashionable in England and known as Robes à lAnglaise. Although we think of historic dress in terms of eras Tudor, Stuart, Georgian, Regency, Victorian fashions changed from one year to the next as much then as now, and the fashion magazines of the time kept ladies informed of the latest modes.

While these changes, from month to month, were slight, taken over the whole twenty-year period of the Napoleonic Wars there were quite significant changes. In Jane Austens novel Northanger Abbey (written in the 1790s) she writes about the heroine and her friend pinning up each others trains for the dance. So if your dress is of an earlier style, then you should pin up the trailing skirt before attempting to dance in it, or, better still, have a little button and worked loop to hook it up securely. By 1815, as I have mentioned above, skirts were a very different shape in the early 1800s they became very narrow, then around 1811-12 the waistline dropped a bit, until by 1815-16 the waist was right up under the bust with a conical-shaped skirt falling from it to an elaborately decorated hem. For a ball commemorating the victory at Waterloo in 1815 this style is ideal.

A word about Court Dress. An even more formal dress was Court Dress, which was only worn for attendance or presentation at Court in the presence of Royalty. Queen Charlotte refused to relax the rules about wearing hooped petticoats, lappets and lace ruffles with Court Dress, regardless of the changing fashions and rising waistlines, with the result that ladies Court Dress took on a bizarre appearance. Tall feathers were worn on the head as wellthey were not compulsory at this time, but most ladies felt under-dressed without them! Needless to say, it would be impossible to dance in such an outfit, but it was not intended that anyone should.

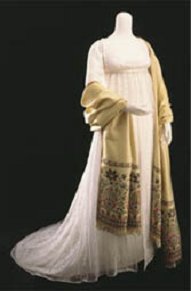

What is interesting is that this was a peculiarly British fashion. It was, of course, based on the formal fashions of the 1760s when George III became King, and these were influenced by the French court. But as fashions changed radically to the simpler neo-classical look and the new Revolutionary France looked to English tailors for mens fashion, the old formal styles were swept away. When Napoleon crowned himself Emperor in 1804, his new court had to invent a new Court Dress. Led by Empress Josephine, formal and court wear for ladies right across the Empire kept to the elegant high-waisted style but used the most elaborate fabrics, with long sleeves, trained robes and Grecian-style diadems. Once again, however, these dresses were status symbols for very formal occasions, and most definitely not worn for dancing.

I have met some visitors from abroad at balls I have attended, with the gentlemen in glittering uniforms and the ladies wearing quite elaborate outfits with trains, who were obviously unused to dancing. Friends of mine who attended balls on the continent a few years ago said that there was very little dancing at that time, and they were more like grand receptions, held in castles or palazzos. My theory is that these re-enactors were recreating the style of the European courts and the Bonapartist aristocracy. French Revolution or not, British society at this time was far more democratic, and we in the English dance groups usually dress in a simpler style consistent with the country gentry and minor aristocracy of Jane Austens world.

Here are a few tips I offered to my re-enactor friends:

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved