| Return to Index |

|

Paper 34 Example Tunes for Country DancingContributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 19th February 2019, Last Changed - 27th December 2021]Thousands of tunes for Country Dancing were published in London alone over the decades, but only a small proportion of them were popular in the ball rooms of the aristocracy and gentry. In this paper we'll consider a few representative examples of the successful tunes from across the Regency era, we'll discover what we can learn about the country dancing industry in the process. Every tune has its own tale of course, the narratives we'll offer here are inevitably incomplete. If you'd like to know more then I can recommend the website of The Traditional Tune Archive as a particularly good source of additional information. The tunes that we will consider in this paper are:

Money in Both Pockets / Trip to Galloway

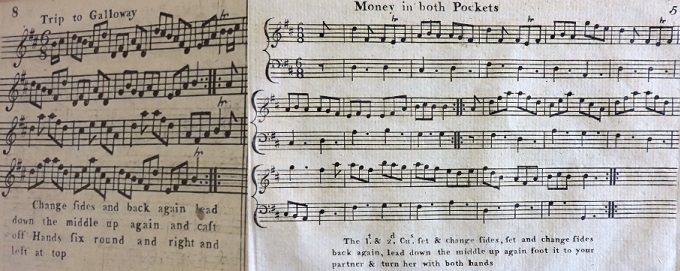

Money in Both Pockets (see Figure 1) is the name of a popular tune that appeared in numerous London dance publications of the early 1790s, it's likely to have arrived in London from Scotland and was printed with various different figure sequences (also referred to as  Figure 1. Trip to Galloway from Campbell's 24 Country Dances for 1784 (left), and Money in both Pockets from Campbell's c.1790 5th Collection (right). Left image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, a.9.d.(3.). ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 1. Trip to Galloway from Campbell's 24 Country Dances for 1784 (left), and Money in both Pockets from Campbell's c.1790 5th Collection (right). Left image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, a.9.d.(3.). ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

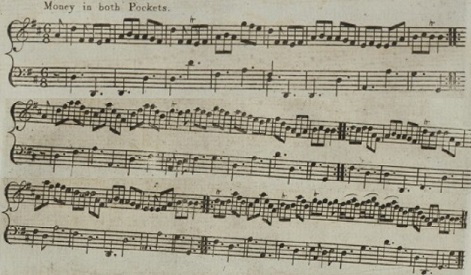

Establishing the true origins of any tune can be challenging, new compositions are inevitably influenced by earlier tunes, and many dance tunes are so simple that they could sound similar to each other by chance alone. It was with this in mind that I noted that the TTA identifies the tune as being similar to another tune named Trip to Galloway; this Anglo-Irish tune was published in London by William Campbell in his Twenty four Country Dances for the Year 1784 (and possibly elsewhere, see Figure 1); the melody is similar to the variant that went on to become popular, especially in the second strain. It's possible that Money in Both Pockets was indeed derived from Trip to Galloway, perhaps indirectly via an intangible process of influence. Both tunes in turn are somewhat similar to the traditional Irish tune of Kinnegad Slashers (though it may only date to the 1790s). It's unclear where Campbell collected the Trip to Galloway tune from; he may have composed it, it may have been a traditional Irish tune, it may have been sourced from an as yet unidentified published collection or otherwise circulated in manuscript form between musicians. Several authorities state that Money in Both Pockets was first published in Edinburgh by Robert Petrie, it's certainly found within his c.1790 A Collection of Strathspey Reels & Country Dances (see Figure 2). It also appeared in several London collections at around the same date. Petrie's version is unusual as it consists of four strains of music; whereas both Trip to Galloway and the London variants of Money in Both Pockets only consist of the first two strains of Petrie's music. Scottish dance publications rarely included any suggested dancing figures, that's as true for this tune as any other. I suspect that Petrie did indeed compose (or at least arrange) the tune as it would go on to be known in London, but I'm suspicious of the 1790 publication date for his collection - I don't know how that date was established and I can't independently corroborate it. Aside: Dating historical publications can be challenging as they often omit a date on the cover. The estimated publication date of 1790 for Petrie's book may be accurate, but I have a suspicion that it may really be a few years older that that. My suspicion is based on several tunes within the collection that became popular in London: Money in Both Pockets, The Washer Woman (better known as The Irish Washer Woman) and Morgan Ratler. All three of these tunes emerged in London at around the same c.1790 date, but Morgan Ratler was published as early as 1787 (for example within Thomas Skillern's The Caledonian Medley Dance for the Year 1787). If Petrie's collection dated from around 1785 or 1786 then it would probably be the direct source (from a London centric point of view) of all three of these popular tunes; if it dates from 1790 then it was clearly influenced by other publications. That in turn would cast doubt on Petrie's identification as the composer of Money in Both Pockets. All three tunes may in fact derive from Ireland, perhaps having been popularised by Petrie in Edinburgh and travelling from there to London.  Figure 2. Money in Both Pockets from Robert Petrie's c.1790 A Collection of Strathspey Reels & Country Dances. Image courtesy of Historical Music of Scotland

Figure 2. Money in Both Pockets from Robert Petrie's c.1790 A Collection of Strathspey Reels & Country Dances. Image courtesy of Historical Music of Scotland

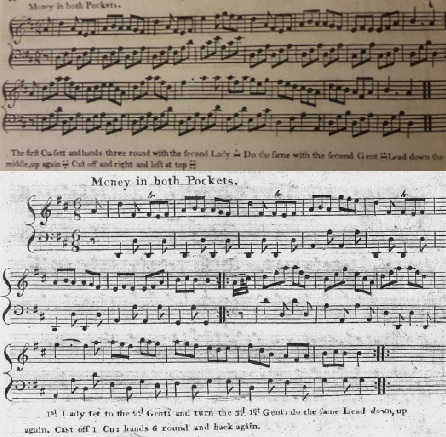

The first publication of the tune under its new name in London is likely to have been within William Campbell's c.1790 Fifth Collection of the newest & most favorite Country Dances and Reels (see Figure 1). The 1790 publication date is only an estimate, we've discussed the process of establishing that estimate here. Campbell's music is very similar to that of Petrie, but it only consists of the first two strains. Campbell was a Scotsman who lived and worked in London, he was often the first of the London publishers to reissue a tune from Edinburgh, and frequently successful in anticipating which tunes would become popular. He had once again found a winning score, the other London music sellers were influenced by his publication, it was widely republished over the next few years. Campbell was not however a great choreographer, his dance figures often leave much to be desired; his Thomas Cahusac also issued a version in his Twelve Country Dances for the Year 1792 (see Figure 3), he arranged a new bass line and offered a different sequence of dancing figures. The Cahusac figures are matched to the strains of music in a more obvious way, but the leading figure is split across the music in an unusual (and perhaps unintentional) manner. The Cahusac music was not a direct copy of the Campbell music, several minor differences can be identified; this might hint that the Cahusac score was transcribed by ear rather than copied from a published source. The Thompson publishing dynasty also issued a version at around the same date in their New Collection of Twelve favourite Cotillons and Twelve popular Country Dances. I don't know when this publication was issued, but it seems early 1790s in content; their version was identical to that of the Cahusacs, except with a different bass score. They reused the Cahusac dancing figure (or perhaps the Cahusacs reused the Thompson figures, I'm unable to establish the precise chronology of publication but it's likely that one actively copied from the other). The Prestons included it in their Twenty four Country Dances for the year 1793, their version reused the tune exactly as published by Campbell, though they only issued the treble score. Their dance figures were similar to those of Campbell, though slightly different once again (and likewise removing the uncertainties present in the Campbell arrangement).  Figure 3. Money in both Pockets from Cahusac's 12 Country Dances for 1792 (above), and from Kauntze's c.1799 Collection of the most favorite Dances, Reels, Waltzes, &c (below). Above Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, a.248.(11.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Figure 3. Money in both Pockets from Cahusac's 12 Country Dances for 1792 (above), and from Kauntze's c.1799 Collection of the most favorite Dances, Reels, Waltzes, &c (below). Above Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, a.248.(11.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Longman & Broderip republished Campbell's premium version of Money in Both Pockets in their c.1792 Second Selection of the most favorite Country Dances, Reels &c.. They duplicated Campbell's version verbatim; every dot and every word was identical, though engraved on new plates. This was not unusual for them, they issued collections in both 1791 and 1792 that were almost entirely derived from Campbell, I'm almost inclined to think of their first two books as Aside: I find it a little ironic that a subsequent publication issued by Joseph Dale c.1799 or 1800 was in turn an almost verbatim copy of Longman & Broderip's c.1791 First Selection. Dale was even more obvious in copying L&B than they had been in copying Campbell; this results in certain Campbellian dances appearing to remain current over nearly three decades, though it's only direct evidence of the corners that some publishers were willing to cut. Examples include Campbell's variants of The Village Maid, The White Cockade, and The Fife Hunt; they were all issued by Campbell in the 1780s, copied verbatim by L&B c.1791, and then recopied by Dale c.1800; Campbell in turn had usually selected the tunes from an even earlier Scottish publication. Campbell invented his dancing figures as the tunes were not choreographed when first published in Edinburgh; these figure combinations remaining associated with the tune could cause confusion if, that is, we were to assume that they had been reproduced by a discerning publisher (someone who intended to record a fashionably meaningful arrangement of figures), rather than being copied in bulk with no evident discernment involved!

Meanwhile, back in Edinburgh, the tune would be published at least a couple more times from around 1792. It appears in Niel Gow's c.1792 A Third Collection of Strathspey Reels &c, and also in Malcolm Macdonald's c.1793 Third Collection of Strathspey Reels & Country Dances. The Gow arrangement is interesting, it was once again issued with additional bars of music attached, but the Gow extensions were different to those of Petrie, the whole tune was arranged to be a little more complicated than the Petrie/Campbell versions. Gow added an extra detail, he reported that The tune then passed a few years seemingly without republication before being issued in London by George Kauntze in his c.1799 Collection of the most favorite Dances, Reels, Waltzes, &c (see Figure 3). The new variant involved yet another new bass score, together with a further sequence of dance figures.

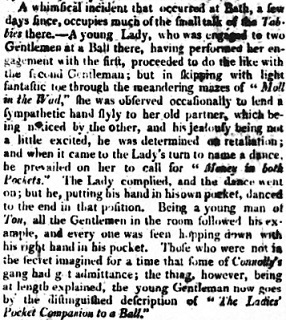

Skipping forwards a few more years, Thomas Wilson issued his Treasures of Terpsichore in 1809; it included suggested figure sequences for over two hundred popular tunes. Wilson provided two new choreographies that were suitable for use with Money in Both Pockets, they were created using his  Figure 4. An incident at Bath. Evening Mail, 21st January 1803. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Figure 4. An incident at Bath. Evening Mail, 21st January 1803. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Further references to the tune can be found in print however. For example, The Globe newspaper for 17th June 1809 reported that The tune of Money in Both Pockets had been arranged with numerous sets of figures by London's publishers over nearly 20 years. This was not uncommon however, a convention existed in the fashionable assembly rooms by which the figures for a dance would be selected in-situ, there was no expectation that the same figures would be danced whenever the tune was played; an anecdote to describe this convention was published in 1803, and it once again involves this same tune. What follows was printed in the Evening Mail newspaper for 21st January 1803 (see Figure 4): A whimsical incident that occurred at Bath, a few days since, occupies much of the small talk of the Tabbies there. --- A young Lady, who was engaged to two Gentlemen at a Ball there, having performed her engagement with the first, proceeded to do the like with the second Gentleman; but in skipping with light fantastic toe through the meandering mazes ofMoll in the Wad,she was observed occasionally to lend a sympathetic hand slyly to her old partner, which being noticed by the other, and his jealousy being not a little excited, he was determined on retaliation; and when it came to the Ladys turn to name a dance, he prevailed on her to call forMoney in both Pockets.The Lady complied, and the dance went on; but he, putting his hand in his own pocket, danced to the end in that position. Being a young man of Ton, all the Gentlemen in the room followed his example, and every one was seen hopping down with his right hand in his pocket. Those who were not in the secret imagined for a time that some of Connollys gang had got admittance; the thing, however, being at length explained, the young Gentleman now goes by the distinguished description ofThe Ladies Pocket Companion to a ball.

The story involved the leading man inventing new dancing figures, and everyone else copying his innovation because he was The tune of Money in Both Pockets experienced an interesting history. Its origins may involve an earlier tune issued in London with an Irish theme; it emerged in its complete form in an Edinburgh publication with additional strains of music; it was then copied and condensed into another London publication (which was coincidentally issued by the same Scotsman who published Trip to Galloway), then featured in numerous further London publications of the next decade, it remained a colloquially recognisable tune in perpetuity. I'll not be at all surprised if further evidence should emerge to push the date of composition further back into the mid 18th century - do contact us if you know more!

Figure 5. Mirza Abu'l Hasan Khan, the Persian Envoy of 1809.

Figure 5. Mirza Abu'l Hasan Khan, the Persian Envoy of 1809.

The Persian Dance / Ricardo / Persian Reveille / Persian Ambassador / PetronellaThe Persian Dance was a tune that burst into general popularity in 1810, it was wildly successful for approximately a year, and then dropped back into obscurity before re-emerging under the name Petronella a few years later. It probably achieved peak levels of high-society saturation before it was ever even published, references to it being danced in the ball rooms of the aristocracy are likely to pre-date any of the dozen or more publications of the tune (in London or elsewhere) from later in 1810. We've animated an arrangement of William Dale's c.1810 version of the dance, and also an arrangement of Skillern & Challoner's c.1810 version and also of Button & Whitaker's c.1810 version.

The tune was reported to have been composed by the Welshman John Parry, a leader of the band at Vauxhall Gardens and a collector and publisher of Welsh melodies. The composition was credited to Parry in several newspapers including the Morning Post for 25th May 1810 which reported

The first reference to the Persian Dance I've found is from the Morning Post newspaper for 4th May 1810, it reported on

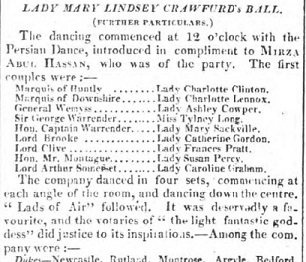

Aside: The entry for The Persian Dance at The Traditional Tune Archive is available here. It alleges that the tune can be found in the Preston collection for 1801, I can't find it in the copy of that work that I have access to. I suspect there's a mistake somewhere. A version provably printed prior to 1810 would be of significant interest.  Figure 6. Lady Mary Lindsey Crawfurd's Ball Morning Post, 11th June 1810. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Figure 6. Lady Mary Lindsey Crawfurd's Ball Morning Post, 11th June 1810. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

The first reference to a published version was advertised by Charles Wheatstone in the Morning Post for 15th May 1810, he advertised availability of

Another society ball was referenced in the Morning Post for the 11th June 1810, this time

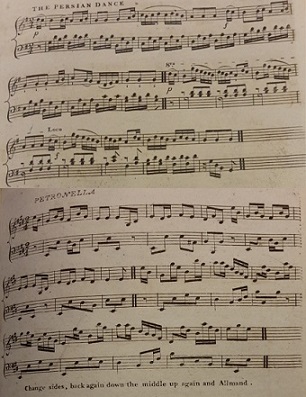

The Public Ledger for 14th August 1810 referenced a fete hosted by the officers of the King's own Stafford Militia, it recorded that  Figure 7. The Persian Dance in Goulding's c.1810 18th Number (above), and Petronella in James Platts' c.1815 45th Number (below). Lower image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(10.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 7. The Persian Dance in Goulding's c.1810 18th Number (above), and Petronella in James Platts' c.1815 45th Number (below). Lower image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(10.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The tune was published by many of London's music shops in 1810 and 1811; most were issued with three strains of music though some only used two; many included a bass line which varied between publications; those that included dancing figures were different in almost each instance (despite being issued at almost the same date). It's impossible to determine a precise chronology, but examples include: George Walker's c.1810 25th Number; Goulding's c.1810 18th Number (see Figure 7); Andrew's c.1810 27th Number; William Dale's c.1810 17th Number; James Platts's 1810 19th Number; Button & Whitaker's c.1810 15th Number; Wheatstone & Voight's 4th Book (the updated 1810 edition); William Campbell's c.1810 25th Book (under the name The Persians Reveille); Skillern & Challoner's 1810 11th Number (under the name Ricardo or the Persian Dance); Cahusac's 12 Country Dances for 1811; Fentum's 24 Favorite Dances for 1811; Robertson's 24 Country Dances for 1811; Goulding's 24 Country Dances for 1811 (under the name The Persian Ricardo); and Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1811 (also under the name The Persian Reveille). It was also published in Edinburgh by Nathaniel Gow in his The Favorite Dances of 1812, and by Muir Wood and Co at a similar date but (unusually for an Edinburgh publication) with dancing figures attached. Three suggested choreographies for the tune were offered by Thomas Wilson in his Supplement to the Treasures of Terpsichore for 1811 under the name Persian Dance; or, Persian Ambassador. Edward Payne also included The Persian Dance in his list of popular three-part tunes in his 1814 A New Companion to the Ball Room.

James Platts published a variant of the tune in his 1811 27th Number under the name The New Persian Dance, then with further modification in his c.1815 45th Number (see Figure 7) under the new name of Petronella (presumably named in dedication to Prince Petrulla of Sicily and Naples who attended several fashionable balls in London in the summer of 1815). This new tune sounds quite similar to the Persian Dance, though it's possible that it was composed independently; it seems likely to be a deliberately obscured variation of it. Platts' new tune was probably the direct source for the tune of the same name that Nathaniel Gow published in Edinburgh in his 1820 The Cries of Edinburgh (where it's described as being Petronella is another tune with a fascinating history; it's usually considered to be Scottish in origin, but it was composed by (or at least derived from a tune composed by) a Welshman living in London, and was dedicated to a Persian dignitary. It was fantastically popular for less than a year and was then largely forgotten in London, it lived on into modern times in Edinburgh. Its popularity was firmly established before it was widely published, it's best known today under a name other than its original.

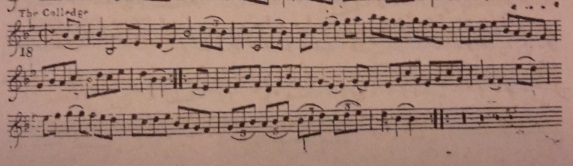

The College HornpipeThe College Hornpipe has a very unusual history; it was first printed in London in the 1750s, disappeared into relative obscurity only to re-emerge towards the start of the 19th century; it went on to be a widely known Hornpipe tune that was often associated with sailors and was even enjoyed by the elite dancers of Almack's Assembly Rooms. We've animated an arrangement of Button & Purday's c.1807 version (see Figure 9).  Figure 8. The Colledge Hornpipe in Thompson's c.1757 First Book of 30 Favourite Hornpipes (the image is from their c.1770 Compleat Collection of 120 Favourite Hornpipes)

Figure 8. The Colledge Hornpipe in Thompson's c.1757 First Book of 30 Favourite Hornpipes (the image is from their c.1770 Compleat Collection of 120 Favourite Hornpipes)

The first known publication of The College Hornpipe is in the Thompson hornpipe collections; they published at least five books of their Collection of 30 Favorite Hornpipes in London between about 1757 and 1771, The College Hornpipe can be located in their c.1757 First book (see Figure 8). These collections recorded stage dancing tunes Aside: Dating these Hornpipe collections is challenging. I've estimated the publication dates by reference to published advertisements issued by the Thompsons as follows: 30 Favourite Hornpipes, Price 1s was advertised in the London Chronicle for 10th November 1757, it was presumably the first collection; A second Collection of thirty favourite Hornpipes, Pr 1s was advertised in The General Evening Post for 8th November 1759; Ninety favourite Hornpipes in three Books, each 1s was advertised in the Newcastle Courant for the 15th October 1763; Thompson's Collection of favourite Hornpipes, Price bound 3s6d was advertised in The Public Advertiser for 21st July 1770, it was presumably a collection of 120 Hornpipes including the 4th book; Thirty Favourite Hornpipes, book 5th, Pr 1s was advertised in The Newcastle Courant for 12th October 1771. I imagine the books were advertised shortly after they were published. I've studied a surviving copy of Thompson's c.1770 Compleat Collection of 120 Favourite Hornpipes; it appears as though the first 30 tunes constitute the 1757 initial collection of 30, the next 30 made up the 1759 second book, and so forth - the tune numbers run from 1 to 30 four times over, the existing plates must surely have been reused for the collected edition.

It's unclear whether the tune was already established at that early date, though it had presumably been used on stage. It must have achieved a degree of popularity by 1765, the date at which a Barrel Organ was advertised for sale with a

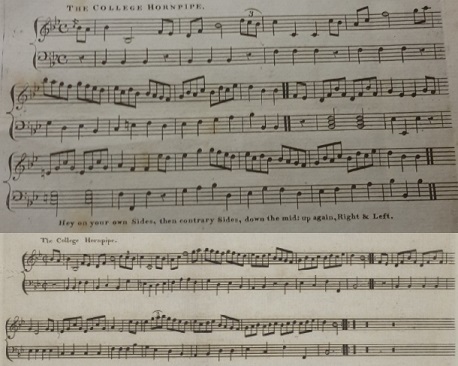

My impression is that the tune continued to be used by vernacular dancing communities throughout the second half of the 18th century, without achieving mainstream popularity. It probably began life as a stage dancing tune, but perhaps it was adopted by sailors (it's often referred to today as  Figure 9. The College Hornpipe in Button & Purday's c.1807 5th Number (above), and in Alexander McGlashan's 1781 A Collection of Scots Measures, Hornpipes, Jigs, Allemands & Cotillons (below). Upper image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.aa ALL RIGHTS RESERVED; lower image courtesy of Historical Music of Scotland.

Figure 9. The College Hornpipe in Button & Purday's c.1807 5th Number (above), and in Alexander McGlashan's 1781 A Collection of Scots Measures, Hornpipes, Jigs, Allemands & Cotillons (below). Upper image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.aa ALL RIGHTS RESERVED; lower image courtesy of Historical Music of Scotland.

The tune began re-emerging into the public consciousness from around 1803, the date at which London's music shops started including it in their collections (without figures). This was no great burst of attention however, just a slowly growing interest, perhaps led by demand from the music purchasing public. Britain's navy fought and won the Battle of Trafalgar in October 1805 under Admiral Lord Nelson, Nelson himself died in the engagement; an outpouring of patriotic emotion may have fuelled the interest in maritime themed music. Examples of the publication of the tune include Robert Mackintosh's c.1803 A Fourth Book of new Strathspey Reels, George Walker's 1804 4th Number, Andrew's c.1805 8th Number, and Dale's c.1805 8th Number. It was published c.1807 by Button & Purday in their 5th Number (see Figure 9), this particular edition is of some interest as it may have been the first London publication to attach suggested country dancing figures to the tune. Goulding & Co included the tune in their c.1812 27th Number. Thomas Wilson included two suggested country dancing choreographies for the tune in his 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore, and three more in his 1816 Companion to the Ball Room; Edward Payne named the tune amongst his popular single-figure country dancing tunes in his 1814 A New Companion to the Ball Room. It was even included in the 1825 Analysis of the London Ball-Room; it's unusual for a tune to be so well known and yet to have been republished so infrequently - most of the London music sellers seem not to have included it in their catalogues.

Passing references to The College Hornpipe can be found in the London press from around 1814 forwards, increasing in frequency over the 1820s and beyond; my impression is that the tune had achieved sufficient popular appeal by the mid 1810s that the public could be expected to recognise the name. The most interesting reference however can be found in an 1860s retrospective account of the dancing at Almack's Assembly Rooms of the 1810s; Almack's was the most prestigious dancing venue in Regency London, a place that fashionable dancers aspired to attend. The anonymous chronicler recalled their youth at Almack's, and wrote of the country dancing: The College Hornpipe is a rare example of a tune that retained relevancy over more than a century, most popular tunes only remained current for a year or two, or a few decades at most. It probably began as a stage tune, but it was adopted for Country Dancing and was enjoyed on both sides of the Atlantic; it probably rose to fashionable prominence in London after first proving popular with the general public. It remained popular throughout the 19th century; it was (for example) referenced in the novels of both Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy, I can recommend visiting the Contrafusion website for further information on the later story of the tune; it's perhaps best known today, at least in Britain, as the theme tune to the veteran children's TV programme Blue Peter.

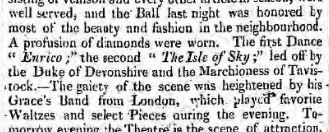

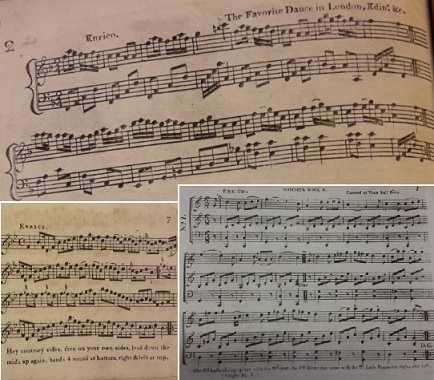

EnricoThe tune named Enrico is not well known today, but it was briefly a Regency era favourite; as with many such tunes, it was probably composed for (or otherwise derived from) a stage production. We've animated an arrangement of James Platts's 1813 version, and also Button & Whitaker's c.1814 version. The heroic comic opera of La caccia di Enrico IV by Pucitta was performed at the King's Theatre in 1809, and again in 1813, to great success. It's likely that this production provided the name for the country dancing tune that became popular in 1813, it may also have provided the melody (I can't confirm or deny this). The opera was frequently mentioned in the press however, not least because of a riot at the theatre after the star performer refused to attend (The Courier, 3rd May 1813). If a public event was being talked about then at least one of London's music shops would invariably issue a tune named for that story; at least three such tunes circulated under the name Enrico in late 1813, none of which may in fact have been derived from the operatic music. A Quadrille dancing tune named Vive Henri IV probably was derived from the opera however, it went on to become popular in 1816 afer being included in Edward Payne's 4th Set of Quadrilles.  Figure 10. Derby Mercury, 26th August 1813. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Figure 10. Derby Mercury, 26th August 1813. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Several tunes may have circulated under the name Enrico, but most of the music sellers issued variants of a single tune, presumably it was this most-published version that was generally known. Each vendor provided their own unique bass accompaniment for the tune, those that issued dancing figures also provided a unique choreography; the tune may have been popular, but (as usual) any figures could be danced to it. Another investigation of the tune is available at The Traditional Tune Archive.

Our first significant reference to the tune involves the Derby Race Ball for 1813, the Derby Mercury (26th August 1813) reported:

The same tune was also named as having been played at two military Balls in 1814. First the Ball of the 14th Light Dragoons (Morning Post, 3rd October 1814), at which the dancing commenced with  Figure 11. The three Enricos, from Nathaniel Gow's 1814 Earl of Dalhouseie (above), Goulding's 24 Country Dances for 1814 (below, left), and Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1813 8th Book (below, right)

Figure 11. The three Enricos, from Nathaniel Gow's 1814 Earl of Dalhouseie (above), Goulding's 24 Country Dances for 1814 (below, left), and Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1813 8th Book (below, right)

Many of the music shops issued copies of the same tune; it's not possible to determine the precise sequence of publishing, but examples include: James Platts's 1813 37th Number; an unnumbered c.1814 collection issued by Martin Platts; Skillern & Challoner's c.1814 20th Number; Button & Whitaker's c.1814 27th Number (this edition included both Single and Double arrangements of figures choreographed by Thomas Wilson, the double arrangement made use of his exotic

Two alternative tunes published under the same name at around the same date include an Enrico from Goulding's 24 Country Dances for 1814 (in 4/4 measure, see Figure 11), and a 6/8 metre tune issued by Charles Wheatstone in several different works including his c.1813 8th Book where it was described as having been Enrico was not a particularly important tune, it went on to be forgotten just as quickly as it had become sensational; but it's a good example of something that regularly occurred within the publishing industry. Once a tune had been named in one of the newspapers, especially in the context of a society ball, London's music shops needed to have a tune of that name ready to sell. If they didn't already have the tune, they'd issue a new publication that did include it (or at least a tune of the same name). Names were often selected based on what was being talked about in the coffee shops, any story that appeared in the newspapers could be used as the name of a tune; this might include the names of battles, people, operas, events, and so forth. The names of tunes are often a good clue for dating them - we just need to know the date at which a name was meaningful, then we can estimate the date at which that name was likely to have been selected. Enrico was a fairly obscure tune, but it did flourish for a year.

SummaryWe've investigated four very different country dancing tunes in this paper. We've seen tunes that were published in Edinburgh become popular in London and tunes published in London become popular in Edinburgh. We've seen tunes of the people be adopted by the nobility and tunes of the nobility be adopted by the people. We've seen tunes grow in popularity over decades and tunes that only lasted a single season. We've seen tunes derived from Stage dancing and tunes named after Stage productions. We've recognised that multiple figure sequences were published for the tunes and that multiple tunes could all share the same name, and yet particular combinations might be favoured. We can infer from all this that the dancing experience 200 years ago must have been both rich and varied. There were many dozens of tunes that were similarly popular at around the same date, but there were thousands more that remained largely unknown. Two clues emerge for identifying the most popular tunes: a statistical analysis of how frequently they were published, and the existence of independent references to the tunes from other sources. The statistical method is most effective when considering tunes published between about 1790 and 1815; prior to 1790 there were insufficient publishers for trends to clearly emerge, and after 1815 the market for tunes collapsed (perhaps in part due to copyright disputes between publishers). But for perhaps a quarter of a century clear trends do emerge. Independent references to tunes are fundamentally anecdotal in nature, there's an element of chance involved in such references having been recorded, but combining both sources of information can help to identify the tunes that were genuinely being danced to. We'll return to consider this subject further in subsequent papers.

But for now we'll leave the investigation here. If you'd like to feature these tunes in a modern

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved