| Return to Index |

|

Paper 37 Programme for a Richmond Ball, 1815Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 27th August 2019, Last Changed - 4th August 2022]There are two Regency era Balls that resonate in the modern imagination to a greater extent than any others, the 1811 Carlton House Ball in London and the 1815 Duchess of Richmond's Ball in Brussels. The first unofficially marked the commencement of the Regency, the latter formed part of the pageantry of the Battle of Waterloo. But, as with most historical Balls, relatively little can categorically be stated about the dancing at these events; this paper investigates a Ball held in the London borough of Richmond in early 1815, it's entirely unrelated to the celebrated Duchess of Richmond's Ball, but it's a rare example of a Ball for which some of the dancing can be rediscovered. In previous papers we've studied two historical Royal Balls of 1813, this paper will investigate a less prestigious Ball of 1815 that (by chance) has a name that might appear more significant than it should.  Figure 1. The Star and Garter at Richmond Hill, c.1804. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 1. The Star and Garter at Richmond Hill, c.1804. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

The tunes and dances that we'll be investigating further in this paper are:

No, not *that* Richmond Ball

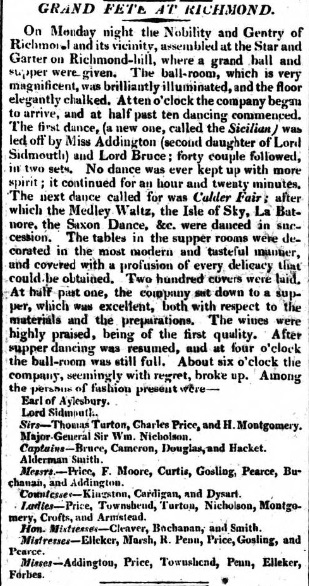

Charles Lennox the 4th Duke of Richmond (1764-1819) lived in Brussels in 1815. His wife was Lady Charlotte Gordon (1768-1842), the oldest daughter of the Duke and Duchess of Gordon; the Gordons had been highly influential amongst London society around the turn of the 19th century, the Duchess of Gordon (c.1748-1812) is often credited with having encouraged the Prince of Wales's personal fascination with Scottish music and dance. The Prince in turn influenced fashion in general. The Gordon's didn't achieve this success in isolation of course; many members of the Scottish peerage travelled with their families to London each year, often to represent their constituents at Westminster; an enclave of rich and influential Scottish peers were active in London, their Balls were amongst the most popular events of the season. Society enjoyed dancing the Reel, the Strathspey and the Highland Fling. The Gordon's were successful in finding partners for their children; their daughters became (through marriage) the Duchesses of Bedford, Manchester and Richmond. It is perhaps fitting that The Duchess of Richmond's Ball of 1815 should be so celebrated today, her family had helped to shape the popular dancing trends of Regency London. Her ball famously featured the family's regiment of Gordon Highlanders performing Reels to entertain the guests; many of those guests were members of the British military command, when word arrived of Napoleon's advancing they were called away to war while still wearing their dress uniforms. The romanticised image of young officers being called from the ball-room to the battle-field endured, the Ball lived on in popular imagination. In the words of the Morning Chronicle newspaper for the 24th June 1815: The Ball we're studying in this paper is not however linked to the Duchess of Richmond. It was hosted in (what is now) the London borough of Richmond on Monday the 23rd January 1815 at the Star and Garter Tavern at Richmond Hill (see Figure 1). Some 200 or more guests attended, including the former Prime Minister (and serving Home Secretary) Lord Sidmouth, also the Earl of Ailesbury together with a couple dozen other notables; most of the clientele seem to have been untitled (though presumably wealthy) local people. This was not a Royal Ball on the scale of the events we've studied previously. One of the London newspapers described the content of the Ball, it did so in sufficient detail for us to investigate the tunes that were played and some of the dances that were enjoyed; what follows was printed in The Globe newspaper for 26th January 1815 (see Figure 2), the dance references have been emphasised: On Monday night the Nobility and Gentry of Richmond and its vicinity, assembled at the Star and Garter on Richmond-hill where a grand ball and supper were given. The ball-room, which is very magnificent, was brilliantly illuminated, and the floor elegantly chalked. At ten o'clock the company began to arrive, and at half past ten dancing commenced. The first dance, (a new one called The Sicilian) was led off by Miss Addington (second daughter of Lord Sidmouth) and Lord Bruce; forty couple followed, in two sets. No dance was ever kept up with more spirit; it continued for an hour and twenty minutes. The next dance called for was Calder Fair; after which the Medley Waltz, the Isle of Sky, La Batnore, the Saxon Dance, &c. were danced in succession. The tables in the supper rooms were decorated in the most modern and tasteful manner, and covered with a profusion of every delicacy that could be obtained. Two hundred covers were laid. At half past one, the company sat down to a supper, which was excellent, both with respect to the materials and the preparations. The wines were highly praised, being of the first quality. After supper dancing was resumed, and at four o'clock the ball-room was still full. About six o'clock the company, seemingly with regret, broke up.  Figure 2. The Grand Fete at Richmond, The Globe, 26th January 1815. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Figure 2. The Grand Fete at Richmond, The Globe, 26th January 1815. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

We might prefer to have more information to work with, but this is a better quality of information than was usually published. Several Country Dances were evidently introduced, together with Waltz couple dancing and a French Country Dance. It's the type of programme that might have been enjoyed at private balls outside of London, and perhaps even in Brussels. We don't have the entire programme for the event, there were evidently some additional dances enjoyed after supper, but we're informed of much of the repertoire for the evening. We'll consider each of the named dances and tunes in turn, but first a brief diversion to consider the preparations for the Ball.

Preparing to Host a BallThe ball-room, which is very magnificent, was brilliantly illuminated, and the floor elegantly chalked. Numerous descriptions of society Balls were published in the London press, some were quite brief and others rather verbose; certain details regularly recur across those descriptions, they help to indicate just how grand an event was considered to be. If a hostess wanted to impress her guests then two of the most important considerations involved illumination and chalking of the floors. These details tend not to be considered for modern recreations of Regency era Balls, but they were of great importance at the time. A particularly wealthy hostess might go further and lure a celebrity orchestra to her Ball (perhaps the Gow Band, or that of Paine of Almacks), or a celebrated chef might be hired to prepare a feast. Flowers and exotic fruit might be liberally distributed, sweetmeats and ices prepared; artificial flowers may be displayed and professional entertainers hired.

Society Balls were usually held throughout the night, suitable illumination was therefore important. Mr Lunardi promised that his balloon themed events at the Pantheon Club in London would be

Floor chalking is an almost lost art form today but it was highly approved of 200 years ago. Chalking involved decorating the floor of a ball room with elegant chalk (or sometimes water-coloured) designs. It's unclear when the convention arose, references to chalking were common from around the start of the 19th century; an early example from a Royal Ball was described in 1804:

The earliest reference I've seen to decorating a floor for dancing dates to 1791. The Bath Chronicle newspaper for the 18th of August 1791 referred to a ball held by the Prince of Wales at Windsor Castle, it reported that Our Richmond ball of early 1815 evidently involved both fancy lighting and chalked floor designs. The expense was presumably on a more modest scale than might be expected of a grand ball but it was sufficient to distinguish the event as being held in an elite style. We'll now return to considering the dances at our Ball.

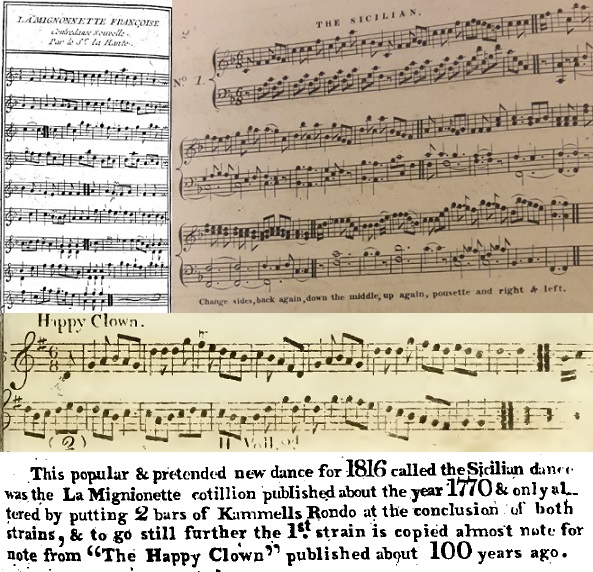

The SicilianThe first dance, (a new one called The Sicilian) was led off by Miss Addington (second daughter of Lord Sidmouth) and Lord Bruce; forty couple followed, in two sets. No dance was ever kept up with more spirit; it continued for an hour and twenty minutes.  Figure 3. The c.1769 La Mignonnette Francoise by Landrin and La Hante (left), The Sicilian from Martin Platts's c.1813 7th Number (right); Happy Clown from James Aird's c.1783 A Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, Vol. II (middle), and Thomas Wilson's declaration concerning the Sicilian Dance from his 1816 Companion to the Ball Room (bottom). Right image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.443.o.(35.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 3. The c.1769 La Mignonnette Francoise by Landrin and La Hante (left), The Sicilian from Martin Platts's c.1813 7th Number (right); Happy Clown from James Aird's c.1783 A Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, Vol. II (middle), and Thomas Wilson's declaration concerning the Sicilian Dance from his 1816 Companion to the Ball Room (bottom). Right image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.443.o.(35.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The ball opened with something quite fascinating, a new dance named The Sicilian that was so popular that it would be danced across two sets of twenty couples over an elapsed period of an hour and twenty minutes. That's a lot of dancing! The leading couple of Miss Addington (1793-1870,

The 80 minute duration of the dance is also surprising. It's difficult to know how seriously to interpret statements of this nature, it seems implausible that anyone could dance with

Many country dancing tunes named the Sicilian Dance (or a minor variation of that name) had been published over the decades up to 1815, I know of at least six candidate tunes. There can be little real doubt about the identification of our tune however, it was published numerous times in London c.1814, this newly popular variant must have been the

One of the most interesting publications of the tune can be found in Thomas Wilson's 1816 Companion to the Ball Room; Wilson issued the tune under the name Sicilian Dance or La Mignionette, but with a fascinating footnote as follows: Returning to La Mignonette, it seems to have first been published in Paris c.1769 under the name La Mignonnette; the composition of the music was credited to Monsieur La Hante and the associated Cotillon figures were choreographed by Monsieur Landrin (see Figure 3). It was then published in London c.1772 by Giovanni Gallini as La Mignonette Francoise. It went on to be published in Edinburgh in Alexander McGlashan's c.1781 A Collection of Scots Measures, and in Neil Stewart's c.1788 A Select Collection of Scots English Irish and Foreign Airs, Jiggs & Marches. It's unclear how this largely forgotten tune of French origin came to re-emerge in London c.1813 with a new name; it's possible that Wheatstone's mysterious Hatton had sold the older tune as his own composition, passing it off as a new creation; it's also possible that La Mignonnette was genuinely popular in Sicily, and a traveller (perhaps our Mr Hatton) had brought it to England under the belief that it was an indigenous Sicilian Air.

However it came about the tune was considered to be new in London in 1815. I have one other reference to the tune being danced socially; it was reported of the early 1814 Christmas Festivities Ball at Brutton-Hall in Yorkshire that For futher references to the tune, see also: Mignonette (1) (La) at The Traditional Tune Archive

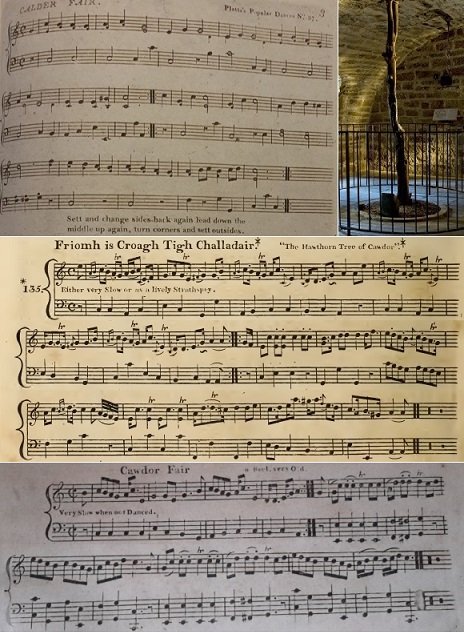

Calder Fair / Cawdor Fair / Hawthorn Tree of CawdorThe next dance called for was Calder Fair;

This is another example of a highly fashionable tune with a much older provenance. It was widely published in London between roughly the years 1813 and 1816, it might even have been thought of as  Figure 4. Calder Fair from James Platts's 1813 37th Number (top left), the Cawdor Hawthorn (top right), The Hawthorn Tree of Cawdor from Captain Fraser's 1816 The Airs and Melodies peculiar to the Highlands of Scotland (middle), and Cawdor Fair from Nathaniel Gow's 1813 Miss Platoff's Wedding (below). Left image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(10.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, right image courtesy of the official Cawdor Castle website.

Figure 4. Calder Fair from James Platts's 1813 37th Number (top left), the Cawdor Hawthorn (top right), The Hawthorn Tree of Cawdor from Captain Fraser's 1816 The Airs and Melodies peculiar to the Highlands of Scotland (middle), and Cawdor Fair from Nathaniel Gow's 1813 Miss Platoff's Wedding (below). Left image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(10.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, right image courtesy of the official Cawdor Castle website.

One of the earlier London publications of the tune can be found in James Platts's 1813 37th Number (see Figure 4), it can also be found in both Goulding's 1814 33rd Number and their c.1815 34th Number (and also in their 24 Country Dances for 1815); it's in an unnumbered Martin Platts collection from c.1814 and also in Wheatstone & Voigt's 1814 9th Book. It's in the Preston collection of 24 Country Dances for 1815 and it replaced

The initial publication of the tune (as far as I can determine) was issued in early 1813; Nathaniel Gow published it in Edinburgh as part of his Miss Platoff's Wedding publication (see Figure 4), the contents of which were described as being

The tune may have been old, but it seems not to have appeared in print prior to 1813. It was known however, Captain Fraser included it in his 1816 The Airs and Melodies peculiar to the Highlands of Scotland (see Figure 4); he issued it under the name Friomh is Croagh Tigh Challadair, or This popular air is mentioned as old, by Mr Gow. The Editor discovering it under the name now given in M.S. of Mr Campbell of Budyet, formerly mentioned, corroborates that truth. The gentleman was a cadet of the family of Lord Cawdor, and a celebrated composer and modeller of our best strathspeys. The hawthorn tree is still visible in Cawdor castle, and is so venerated as the roof-tree of the family, that, on an annual meeting of his Lordship's tenants, and other friends, usually held on the day of Cawdor fair, to drink prosperity to the family, the company merely nameThe hawthorn tree,- hence the probability of its having been composed by Mr Campbell for the occasion.

Indeed, the celebrated Hawthorn tree still stands in the cellar of Cawdor Castle even today (see Figure 4). The Castle's official website records the ancient story of the tree: Our dancers of 1815 are unlikely to have known of these origins of the tune, it was simply a popular dancing tune that had been circulating for perhaps a year or more. We've animated a suggested arrangement of James Platts's 1813 version and of Wheatstone & Voigt's 1814 version. For futher references to the tune, see also: Calder Fair at The Traditional Tune Archive

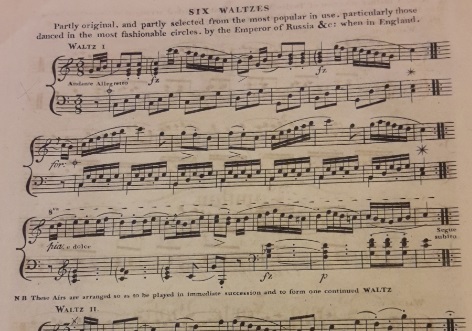

Waltz Medleyafter which the Medley Waltz,  Figure 6. The start of Skillern & Challoner's waltz medley in their c.1815 22nd Number. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.925.o ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Figure 6. The start of Skillern & Challoner's waltz medley in their c.1815 22nd Number. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.925.o ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The couple waltz is a dance form that we've written about before. The Waltz had been growing in popularity in London since the 1790s, it had reached a critical mass of popular appeal by around the middle of 1814, the date of the visit to London of the Tsar of Russia and the Allied Sovereigns. 1814 was a time of celebration in Britain; the year opened with military and political successes that rapidly led to the exile of Napoleon and a general peace in Europe, the year concluded with a celebration of the Brunswick Centenary (100 years of the reign of the Hanoverian dynasty); it might be argued that the giddy freedoms of the couple-waltz matched the celebratory mood of the nation. Anti-waltz moralists continued to resist the new dance form of course, but with little effect; waltzing was increasingly normalised in the ball rooms of the aristocracy. You might like to refer to our paper on the Waltz to read more. It's interesting to find a Waltz medley being danced at our Ball in 1815, it's a very different form of dancing to the Country Dances that preceded it earlier in the evening.

A

Numerous references to waltz medleys being danced in London exist across the 1810s, some refer to

One of my favourite Waltz references can be found in the Chester Courant newspaper for the 4th February 1817, it quoted a correspondent who wrote that:

Figure 6 shows the start of a Waltz Medley as published by Skillern & Challoner in their 1815 22nd Number; their publication is made up of six separate waltz tunes that were

Isle of Sky... the Isle of Sky, .. The Isle of Sky was a veteran dancing tune, we've written about it before as it was featured in one of the Royal Balls that we studied from 1813. It was evidently a favourite. It had been published many times in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, it experienced a burst of publishing interest in London c.1813. You might like to refer to our previous paper for more information on this tune.

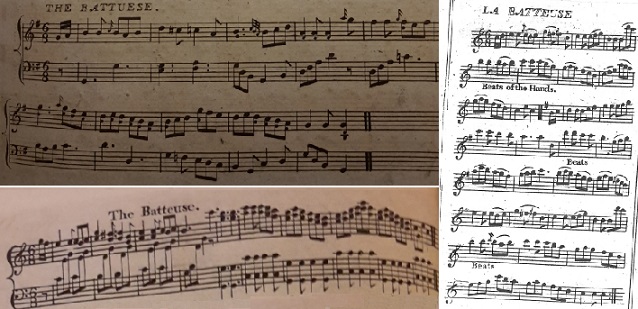

Figure 7. The Battuese from James Platts's 1813 38th Number (top); The Batteuse from Nathaniel Gow's 1815 Lady Hunter Blair's Reel and Waltz (bottom); and La Batteuse from Charles Wheatstone's c.1817 A Selection of the favorite Quadrilles or French Dances (Right). Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(10.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 7. The Battuese from James Platts's 1813 38th Number (top); The Batteuse from Nathaniel Gow's 1815 Lady Hunter Blair's Reel and Waltz (bottom); and La Batteuse from Charles Wheatstone's c.1817 A Selection of the favorite Quadrilles or French Dances (Right). Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(10.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

La Batteuse... La Batnore, ...

The next dance is a little difficult to investigate as the title is hard to read (see Figure 2), it appears to name a dance called

Whether La Batteuse really was danced at our Ball isn't certain, it's possible that the missing La Batnore may surface at some point in the future; La Batteuse is nonetheless the type of dance that may have been introduced and it was sufficiently well known to be casually named in a newspaper. We've written about La Batteuse in detail elsewhere, you might like to follow the link to read more. A quirk of La Batteuse is that it was danced to ten bar strains of music rather then the typical eight or four bar strains of most social dancing; it involved clapping of the hands and fancy stepping during the unforgiving solo passages of the dance. A skilled dancer could show off, whereas a novice dancer probably wouldn't attempt the dance at all! These choreographed dances had the advantage that they offered a burst of excitement for a party; a traditional Country Dance might extend for forty or more minutes as the leading couple slowly progressed their way down the set (perhaps 80 minutes in the case of The Sicilian above), whereas a French Country Dance might take only five or ten minutes to perform, and each of the dancers would receive an approximately equal share of the activity. The French Country Dance (as with the couple Waltz) offered instant gratification, it would go on to dominate the ballrooms of the 1820s in the form of the Quadrille. Our Richmond ball was perhaps a little ahead of its time; Figure 7 shows three different musical arrangements for the La Batteuse French Country Dance that were issued between about 1813 and 1817; all three depict the unusual 10 bar strain of music for which the dance was known. Several different tunes circulated for use with the dance; further examples, along with the dancing figures, can be found in our separate paper on this dance.

It was shortly after our 1815 date that the First Set of Quadrilles began their rapid rise to prominence, by around 1818 most interest in La Batteuse had faded as the Quadrilles had replaced it. There was a brief period of time between about 1800 and 1816 during which the terms

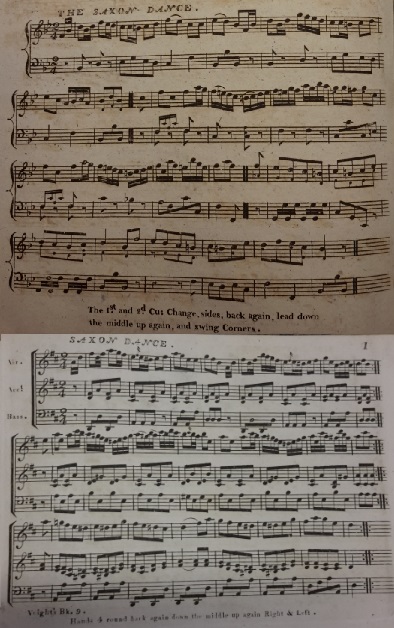

The Saxon Dance Figure 8. The Saxon Dance from James Platts's 1814 41st Number (top) and Saxon Dance from Wheatstone & Voigt's 1814 9th Book (bottom). Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(10.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, bottom image © VWML, EFDSS.

Figure 8. The Saxon Dance from James Platts's 1814 41st Number (top) and Saxon Dance from Wheatstone & Voigt's 1814 9th Book (bottom). Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(10.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, bottom image © VWML, EFDSS.

... the Saxon Dance, &c. were danced in succession. This was another fresh and briefly popular tune, it was widely published in London between 1814 and 1815; as with several other popular tunes its precise provenance is open to debate. One of the first publications of the tune was that of James Platts, it can be found in his 1814 41st Number (see Figure 8). Platts would subsequently claim in his 1815 copyright disputes to own the rights to this tune; this might imply that he was genuinely the first to publish, but the story is a little more complicated than that. Other early publications include those of Skillern & Challoner in their c.1814 21st Number and Wheatstone & Voigt in their 1814 9th Book (see Figure 8). It was also published in William Campbell's Collection for 1815, Martin Platts's c.1815 8th Number and in collections issued by Charles Wheatstone, Christmas & Falkner, Clementi, Dale, Munro and probably others. A second tune with the same name was also in circulation, the rival tune was published at around the same date by Bland & Weller in their collection of 24 Country Dances for 1816 and in Davie's 34th Number; there can be little credible doubt that the widely published tune was the popular variant.

The publishing company of Button & Whitaker issued the tune in their c.1815 reprint of their originally 1813 24th Number. The first edition of their publication included a tune named Prince Kutusoff, it transpired that there were copyright concerns involving that tune, so they replaced it c.1815 with the supposedly uncontroversial The Saxon Dance. Unfortunately The Saxon Dance in turn was also subject to a copyright dispute and they were required to defend themselves in court. James Platts (against whom they had won a copyright dispute in 1814) accused them of copying several of his tunes, including The Saxon Dance. He claimed to have purchased the rights to this tune from Carl Böhmer for

It's not possible to reconstruct the precise sequence of events involving our tune, but I suspect that Platts really was the first to publish the tune in 1814; he may have paid Böhmer at that date, he may not have done (a tune of European origin wouldn't necessarily be subject to British copyright, so there may not have been a payment); there was no reason to expect this specific tune to be successful so no particular care was taken to protect it. The tune was, however, proving popular with the public (e.g. at our Richmond ball of 1815) and the other music sellers began reissuing it in the belief that it was

Returning to 1815, Button & Whitaker made an interesting counter accusation in their defence, they claimed that The Saxon Dance was itself We've animated suggested arrangements of James Platts's 1814 version (see Figure 8), Wheatstone & Voigt's 1814 version (see Figure 8), Skillern & Challoner's c.1814 version and of Martin Platts's c.1815 version.

Conclusion

We don't have the complete programme for this 1815 Ball, what was recorded shows an event at a transitional moment in time featuring a mixture of Country Dances and more modern dance forms. The named tunes were all in fashion in 1815, some were of recent composition while others were older, but they were all considered to be It's possible that a similar programme of dancing would have been enjoyed a few months later in Brussels at The Duchess of Richmond's Ball; the dances and tunes we've investigated were clearly well known, if you would like to recreate an 1815 Ball then these tunes and styles of dancing would all be suitable to use. We'll leave the investigation here, if you have further information to share, please do Contact Us as we'd love to know more.

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved