| Return to Index |

|

Paper 39 The Marchioness of Abercorn's Balls of March 1801Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 24th October 2019, Last Changed - 26th September 2024]The recently married Marchioness of Abercorn hosted two Grand Balls in London in March 1801. The Abercorns were members of the Irish peerage and they were very well connected; their events were described in the London press in sufficient detail for us to study the dancing. In this paper we'll investigate what we can learn of the dances used at these two 1801 events.  Figure 1. A view of Grosvenor Square, 1789. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 1. A view of Grosvenor Square, 1789. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

The tunes and dances we'll be investigating further in this paper are:

The Marchioness of Abercorn's Grand BallsOur first ball was hosted on Wednesday 18th March 1801 at the Marchioness's London town house at No 25 (formerly No 22) Grosvenor Square (see Figure 1); the hostess was Lady Anne Jane Hamilton (formerly Hatton, nee Gore) (1763-1827), she was the third wife of John Hamilton, 1st Marquess of Abercorn (1756-1818). The Abercorns were married in April 1800, our 1801 Balls were the first society events that they had hosted since their marriage, they were evidently celebrating. The second of their two balls was hosted less than a week after the first on Tuesday 24th March 1801. Anne was a daughter of the Earl of Arran of the Irish peerage. Their magnificent home in Grosvenor Square occupied one of the more prestigious residential addresses in London, the property had even been considered as a potential home for Prime Minister Lord Bute back in the 1760s; the British History Online website records that the Marquess significantly modified the house between 1799 and 1800, their Balls of 1801 may have offered a grand unveiling of the results to their friends. More than that, the balls may have helped to erase the infamy (which we'll get to in just a moment) that had become attached to the Marquess!  Figure 2. Modern Marriage a-la-mode, 1800. Image courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Collection.

Figure 2. Modern Marriage a-la-mode, 1800. Image courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Collection.

The Abercorns had both been married previously and there was a degree of scandal associated with their union. The public can be cruel, Figure 2 is an Isaac Cruickshank print dated 6th May 1800 that openly ridiculed them. They were married on the 3rd April 1800, it was his third marriage and her second; he had recently been divorced from his second wife having first proved her adultery in a very public case of Criminal Conversation (Evening Mail, 19th December 1798). For example, the Ipswich Journal (17th November 1799) wrote: The Abercorn's marital arrangements were a general talking point and they'd only just got married! Figure 3 shows both of the Abercorns, together with the eldest daughter of the Marquess (Lady Harriet Hamilton (17801803)), as they might prefer to have been remembered.

Before we return to 1801 it's worth considering another singular and unpleasant event that may have been related to the divorce and remarriage. Several newspapers carried the story in March 1800 (shortly before the date of their wedding); for example the Ipswich Journal for the 22nd March 1800 wrote: The Abercorn's seemed destined to suffer ill luck; despite the best laid of plans, the dates of their 1801 balls were problematic - they clashed with a period of official Court mourning. If the Court was in mourning then social activity would be curtailed, the nobility were expected to act with due solemnity. The Lord Chamberlain announced two periods of mourning in early 1801, the first in memory of Hereditary Princess Louisa Charlotte of Saxe Gotha between the 1st and 12th of February; the second for her Royal Highness Philippina Charlotte, Duchess Dowager of Brunswick between the 19th of March and the 30th of April. The first Abercorn ball was held on the 18th of March, the day before the second period of mourning was scheduled to commence. Duchess Louise Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (1779-1801) had died on the 4th January 1801, she was to be mourned for nearly two weeks at the start of February 1801; Princess Philippine Charlotte of Prussia (1716-1801) was a grand-daughter of King George I (and first cousin once removed of King George III), she had died on 17th February 1801 and would be mourned for six weeks. The second period of mourning had only been announced on the 16th March (Morning Chronicle, 18th March 1801), it was too late for the Abercorns to significantly alter their plans; our hostess was lucky in her first date as her guests involved many court fashionables, including two royal dukes and Prince William of Gloucester (1776-1834) who might not attend during mourning. The second Ball a week later did coincide with the official period of Court mourning, the extent to which this dampened the festivities is unclear, but the attendees did include the Prince of Wales himself. Reasonably detailed accounts of the two Balls survive, including a list of the tunes that were used for dancing together with a lengthy guest list. Most society Balls were not reported upon in this much detail. The Abercorn balls have no great claim to historical significance, many dozens of similar balls were held in London at a similar date, their interest lies in the quality of information that was recorded for posterity. The dances at these events were representative of the type of dancing that might be experienced at other society balls of a similar date.

Dancing during Court MourningDancing during court mourning is an interesting subject. It wasn't forbidden to host a society Ball during Court mourning but it should have subdued the entertainment, many guests would be wearing the court sables (black) and some would not attend at all. Strict rules of dress were enforced at Court, the nature of which might vary at different dates throughout the mourning; socialites weren't obliged to follow these conventions elsewhere, but many would voluntarily do so. The Chamberlain's order for February 1801 (as printed in the Morning Post, 31st January 1801) declared:  Figure 3. The Marquess of Abercorn (top), the Marchioness of Abercorn (middle), Lady Harriet Hamilton (bottom).

Figure 3. The Marquess of Abercorn (top), the Marchioness of Abercorn (middle), Lady Harriet Hamilton (bottom).

The Ladies to wear black silk, fringed or plain linen, white gloves, necklaces and ear-rings, black or white shoes, fans, and tippets. Undress - white or grey lusterings, tabbies or damask. The gentlemen to wear black full trimmed, fringed or plain linen, black sword and buckles. Undress - grey frocks. This order involved roughly a week of heavy mourning followed by a week of lighter mourning. The announcement covering March and April was more severe in duration; this was appropriate considering how closely the deceased Princess was related to King George III, this time there were three distinct stages (Morning Chronicle, 18th March 1801): The Ladies to wear black silk, plain muslin or long lawn, crape or love hoods, black silk shoes, black glazed gloves, and black paper fans. Undress - Black or dark grey unwatered tabbies. The Gentlemen to wear black cloth, without buttons on the sleeves or pockets, plain muslin or long lawn cravats and weepers, black swords and buckles. Undress - Dark grey frocks.

An anecdote of how mourning affected another event at a similar date survives. Lady Saltoun held a Ball on the 13th April 1801 while the more intense period of court mourning remained active; The Courier newspaper (18th April 1801) noted of the Saltoun Ball that

Description of the First Ball, 18th March 1801Let's consider the first of our two balls. The following description of the First Ball was printed in The Morning Post newspaper for 23rd March 1801; any dance references have been emphasised in bold. The Marchioness of Abercorn's first entertainment since her marriage was a splendid Ball, on Wednesday evening, at the family residence in Grosvenor-square. This magnificent house has recently undergone a thorough repair, and now ranks equal, if not superior, to most of the noble mansions in town. The following distinguished personages formed a part of the assemblage, amounting to upwards of three hundred, present at the Ball:

One of the unusual details of this ball is that we're told the

We're also informed of some of the culinary delights at supper: The named dancers for the first dance were:

It might be noticed that most (but not all) of the dancers were single, the daughters of the host received a prestigious location at the head of the set, and that the gentlemen were somewhat older than the ladies.

Description of the Second Ball, 24th March 1801The following description of the Second Ball was printed in The Morning Post newspaper for the 30th March 1801; any dance references have been emphasised in bold: The second assembly was on Tuesday evening attended by upwards of 300 personages of distinction, among whom were the following: This second ball was attended by the Prince of Wales himself; not only that, but he stayed for supper (contrary to his normal behaviour), despite the official Court mourning. Perhaps the rumours of asparagus and turtle soup from the preceding ball had lured him to stay! The ball room would presumably have retained its decoration as a hop ground from the previous week. The named dancers for the first dance were:

Once again the dancers were mostly unmarried and the men were generally a little older than their partners. Two of the married ladies were daughters of the Duchess of Gordon, their family had a reputation for enjoying a good dance! Some of the tunes at this second ball were shared across both events; we'll now consider each of the tunes from the two balls in turn.

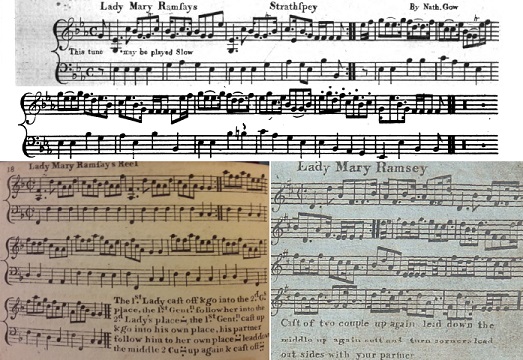

Lady Mary Ramsay's StrathspeyAt eleven o'clock the music struck up with Lady Mary Ramsay, and soon the Ball was opened by Lord Frederick Montague and Lady Harriet Hamilton(First Ball)  Figure 4. Lady Mary Ramsays Strathspey from Gow's 1800 Fourth Collection of Strathspey Reels (top), Lady Mary Ramsay's Reel from Budd's 1801 31st Book (left) and Lady Mary Ramsey from Thompson's 24 Country Dances for the Year 1802 (right). Left image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, a.9.e.(2.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 4. Lady Mary Ramsays Strathspey from Gow's 1800 Fourth Collection of Strathspey Reels (top), Lady Mary Ramsay's Reel from Budd's 1801 31st Book (left) and Lady Mary Ramsey from Thompson's 24 Country Dances for the Year 1802 (right). Left image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, a.9.e.(2.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

This dance was led off by Lady Harriet Hamilton (17801803) the oldest daughter of the Marquess of Abercorn by his first wife (see Figure 3) and Lord Frederick Montague (1774-1827), the younger brother of the Duke of Manchester. Inviting the daughter of the host to lead off the first dance seems to have been a common convention, the same pattern is found at many other private balls.

A tune variously named as Lady Mary Ramsay, Miss Mary Ramsay or Lady Mary Ramsey was widely published in London from around the year 1801, it was evidently a favourite tune. It was sometimes issued with the suffix of

Early London publications included Thomas Budd's 1801 31st Book under the name The tune was dedicated to the Lady Mary Ramsay (1780-1866) the youngest daughter of the 8th Earl of Dalhousie (c.1730-1787). She married James Hay of Drum on the 29th April 1801, mere weeks after the first of our Abercorn balls (Caledonian Mercury, 30th April 1801). She must have been aware that the tune named for her had become popular in London, though what she may have thought of it can only be guessed. The tune was widely enjoyed at society balls across the first decade of the 19th century; the first such reference involves a Ball hosted by the Queen in London (Caledonian Mercury, 6th January 1800), it would be used a few days later by Nathaniel Gow in Edinburgh at an Assembly held in honour of the Queen's Birthday (Caledonian Mercury, 23rd January 1800). It's likely that John Gow promoted his brother's tune in London and that Nathaniel capitalised on the tune's success in Edinburgh; Nathaniel's publication was registered for copyright purposes at Stationer's Hall on the 11th January 1800, perhaps hinting at the success the Gows expected the tune to receive. The tune was used at several Balls in 1801, including the first of our Abercorn Balls and another hosted by the Abercorns in May 1801 (Morning Post, 20th May 1801); it also featured at Mrs Walker's Ball in 1801 (Morning Post, 15th May 1801). It appeared at a ball in 1802 (Morning Post, 30th August 1802), at both Mrs Pole's Ball of 1804 (The Courier, 29th February 1804) and Lady Carnegie's Ball (Morning Post, 27th April 1804). Lady Dalrymple Hamilton used the tune in her Ball of 1806 (Morning Post, 19th April 1806) as did The Hon. Mrs Robinson (Morning Post, 28th April 1806). It evidently remained in fashionable use over several years. We've animated suggested arrangements of William Campbell's c.1802 version, Davie's c.1802 version, and of Henry Thompson's 1802 version (see Figure 4). For futher references to the tune, see also: Lady Mary Ramsay (1) at The Traditional Tune Archive

Paddy O'Rafferty / Paddy O'FlanaganThe second dance was Paddy O'Flaherty(First Ball and Second Ball)

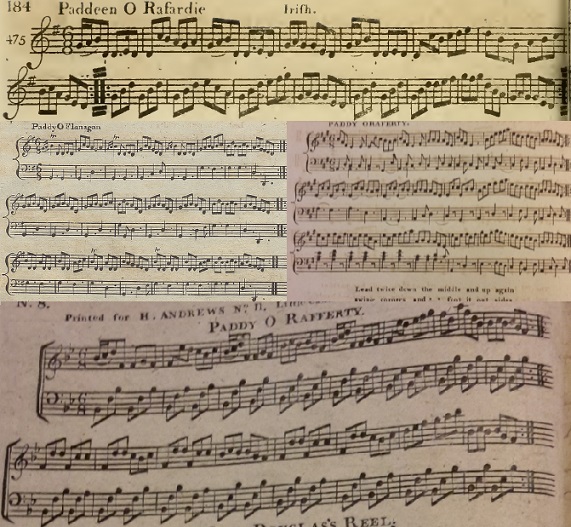

This tune was the second to be danced at both of our Abercorn Balls, it must have been a family favourite. It might have been popular with the Abercorns, but unfortunately it's not a tune that I can identify with certainty; a dozen or more tunes were issued around the start of the 19th Century variously named for  Figure 5. Paddeen O Rafardie from Aird's c.1788 Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, Vol 3 (top), Paddy O'Flanagan from Campbell's c.1802 17th Number (left) and Paddy O'Rafferty from Campbell's c.1804 19th Number (right), and Paddy O Rafferty from Andrew's c.1805 8th Number. Right image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.96. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 5. Paddeen O Rafardie from Aird's c.1788 Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, Vol 3 (top), Paddy O'Flanagan from Campbell's c.1802 17th Number (left) and Paddy O'Rafferty from Campbell's c.1804 19th Number (right), and Paddy O Rafferty from Andrew's c.1805 8th Number. Right image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.96. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

If we can assume that the title given in the newspapers is incorrect (or at least, not the more common title) then perhaps one of the well known tunes was intended. In which case the most likely candidates would be

The provenance of this family of tunes is a little mysterious. The initial publication seems to have been in James Aird's c.1788 Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, Vol 3 published in Glasgow under the name

The first of the London publications may have been in William Campbell's c.1802 17th Book under the name

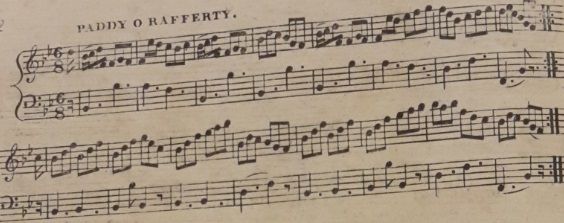

The Preston publishing firm printed a version of the tune in their 24 Country Dances for 1803 under the name  Figure 6. Paddy O Rafferty from George Walker's c.1805 9th Number. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.925.f. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 6. Paddy O Rafferty from George Walker's c.1805 9th Number. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.925.f. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Numerous Rondo arrangements of the tune were issued in London around 1805 and Nathaniel Gow issued a version in Edinburgh in his c.1810 Marquiss de la Romanas Waltz publication. Thomas Wilson referenced the tune in his 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore and also printed a version in his 1816 Companion to the Ball Room. Versions of the tune were issued in Dublin by both Tracy and Hime, the publication dates for those works are uncertain however - it's possible, perhaps likely, that they were issued after the tune had become popular in London. It seems almost certain that the Paddy O'Rafferty tune was danced at our two Abercorn balls of 1801. It went on to appear in The Countess of Malmesbury's Ball in 1804 (The Courier, 18th April 1804), Mrs Morton Pitt's Ball (Morning Post, 26th July 1804) and also at a Public Breakfast later that same year (Morning Post, 8th August 1804). It was used at a 12th Night Ball in early 1805 (Morning Post, 9th January 1805), a Royal Ball at Frogmore (Morning Post, 27th April 1805) and also at a Ramsgate Ball (Morning Post, 18th September 1805). The Abercorns might have introduced the tune to London but it came to be more generally adopted.

There were many Scottish tunes (or tunes that were considered to be Scottish) that were popular in London at the start of the 19th Century, but far fewer successful tunes that were credited as being Irish in origin. This tune is perhaps unusual as probably being of genuine Irish origin. We've animated suggested arrangements of For futher references to the tune, see also: Paddy O'Rafferty (1) at The Traditional Tune Archive

Cary Owen / The Garyon / Harlequin Amulet... and the third the lively one of Cary Owen(First Ball)  Figure 7. Auld Bessy from Aird's c.1788 Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, Vol 3 (top), The Garyon from Cooke's Collection of Favorite Country Dances for the present year 1797 (middle), and Garey Owen from Campbell's 1801 16th Number (bottom).

Figure 7. Auld Bessy from Aird's c.1788 Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, Vol 3 (top), The Garyon from Cooke's Collection of Favorite Country Dances for the present year 1797 (middle), and Garey Owen from Campbell's 1801 16th Number (bottom).

This tune is readily identifiable, it's another tune thought to be of Irish origin that was (probably) first published in Scotland and became popular in London from the start of the 19th Century. Once again it's a tune that may have been promoted by the Abercorns before it went on to be widely printed.

As with

Aside: dating historical publications is often a difficult task. I note that several authorities ascribe the first publication of this tune to a c.1785 London publication issued by Edward Light named Introduction to the Art of Playing on the Harp-Lute & Apollo-Lyre. Light's publication could have included this tune, but as far as I can discern it was first published in 1811 not 1785 (e.g. as advertised in the Morning Post for the 2nd November 1811). The Harp-Lute itself seems not to have been invented until 1795, I'm fairly sure that Light was not significant to the early history of our tune.

The score for Harlequin Amulet might have been printed in London c.1800 (I can't confirm this), but our tune was certainly arranged as a Rondo in Dublin and printed by Hime a year or two later under the name Gary Owen. The first London publication I can actually confirm is that of William Campbell in his 1801 16th Book under the name Garey Owen (see Figure 7, bottom). Campbell described the tune as

The Abercorns promoted the tune in their first Ball of 1801, this may have been the prompt that Campbell needed to publish the tune. It was widely available in London shortly thereafter. Other early examples include Walker's c.1802 2nd Number, Bland & Weller's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1802, Dale's c.1802 1st Number, Preston's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1802 and Cahusac's collection of 12 Country Dances for 1802 (where it is described as having been Danced by the stage performer St Pierre). Other publications include Button & Purday's c.1806 1st Number and Andrew's c.1804 6th Number. It was also published in Edinburgh by Nathaniel Gow in his 1802 Three Favorite New Strathspeys & one Reel where it was described as

There are several references to the tune being enjoyed at London society Balls. After the first of our Abercorn balls in 1801 it went on to be enjoyed at Lady Cornwall's grand ball (Morning Post, 13th April 1801), at Lady Saltoun's Ball (The Courier, 18th April 1801), at The Duchess of Chandon's Ball (Morning Post, 5th May 1801), at the Marchioness of Abercorn's third ball (Morning Post, 20th May 1801) where We've animated suggested arrangements of Campbell's c.1801 version, Cahusac's 1802 version, and Button & Purday's c.1806 version. For futher references to the tune, see also: Garryowen at The Traditional Tune Archive

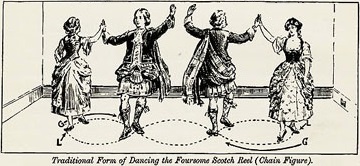

Reel of FourLord Dalkeith and a friend of his Lordship's, danced a Highland Reel with Lady Georgiana Gordon and Miss Maxwell(First Ball)  Figure 8. A Foursome Reel, from the Illustrated Guide to the National Dances of Scotland, 1910.

Figure 8. A Foursome Reel, from the Illustrated Guide to the National Dances of Scotland, 1910.

Both of our Abercorn Balls involved a Reel of Four being performed. We've written about a similar Reel of Four that was performed in 1799 at the Duke of York's Oatlands Fete, you might like to read our description of the dance there in order to learn more; one of the performers in 1799 was Lady Georgiana Gordon (1781-1853), she was a daughter of the celebrated Duchess of Gordon and also one of the performers at the first of our Abercorn Balls; she would go on to marry the Duke of Bedford in 1803. The other performers at the first Abercorn Ball were Charles Montagu-Scott (1772-1819) (Earl Dalkeith and later the Duke of Buccleuch), an unnamed friend of the Earl, and Miss Maxwell a niece of the Duchess of Gordon. The dancers at the second Abercorn Ball were Lady Harriet Hamilton (1780-1803, see Figure 3) and Lady Catherine Hamilton (1784-1812), two of the daughters of our host, the Marquess of Abercorn. Their partners were Lord John Campbell (1777-1847) later the Duke of Argyll, and Mr Thomas Sheridan (1775-1817), gent. Their Reel was the closing dance of the second Ball. The Reel was increasingly popular in London around the start of the 19th Century, it was often danced towards the end of a Ball when many of the guests were tiring.

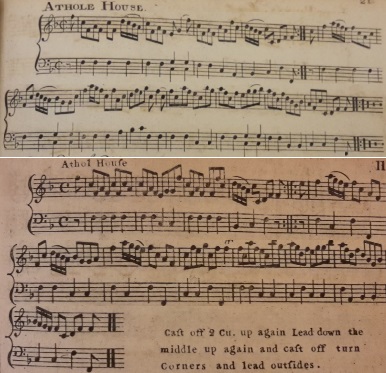

Athole HouseAt half past two o'clock the Ball recommenced with a much admired dance called Athol House(First Ball)  Figure 9. Athole House from Dow's 1773 Twenty Minuets and Sixteen Reels or Country Dances (top), and Athol House from Campbell's c.1780 Sixteen New Dances (bottom). Bottom image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, a.9.e.(6.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 9. Athole House from Dow's 1773 Twenty Minuets and Sixteen Reels or Country Dances (top), and Athol House from Campbell's c.1780 Sixteen New Dances (bottom). Bottom image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, a.9.e.(6.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

A tune named Athole House is quite well known, it was published many times in both Edinburgh and London from the 1770s forwards.

The tune was composed by Daniel Dow (1732-1783) and was first issued in Edinburgh in his 1773 Twenty Minuets and Sixteen Reels or Country Dances (see Figure 9, the collection was advertised as The name Atholl House refers to Blair Castle in Perthshire, the seat of the Dukes of Atholl. The Duke in 1773 was John Murray (1729-1774), the tune was effectively dedicated to him. The publication history of the tune is complicated; it is understood to have been popular in Edinburgh in 1773, the next publication I can identify is that of William Campbell in London in his c.1780 Sixteen New Dances (see Figure 9). It was then republished in Edinburgh in Alexander McGlashan's c.1786 A Collection of Reels and in Glasgow in James Aird's c.1788 Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, Vol 3. It was published in London in Longman & Broderip's c.1794 Fourth Selection of the most favorite Country Dances, Reels &c., then in their Twenty Four Country Dances for the Year 1796, and then in Edinburgh in Robert Petrie's c.1796 A Second Collection of Strathspey Reels &c and in Niel Gow's 1799 Part First of the Complete Repository of Original Scots Slow Strathspeys and Dances. It was published again in London in William Campbell's c.1804 19th Book, in Joseph Dale's 1805 5th Number, in Napier's c.1806 Selection of Dances & Strathspeys and in Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 1st Book. The tune seems to have been known across both the nation and the decades, but there was no burst of publishing interest of the type usually experienced when a tune suddenly became popular in London. The tune was danced at least a couple of times at society balls in London; first at our Abercorn ball, then a few months later at The Duchess of Gordon's Ball (Morning Post, 22nd July 1801). It would be mentioned again nearly a decade later as having been danced at the Perthshire Hunt Ball (Perthshire Courier, 8th October 1810). We've animated suggested arrangements of Campbell's c.1780 version (see Figure 9), Campbell's c.1804 version and Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 version. For futher references to the tune, see also: Athol(l) House at The Traditional Tune Archive

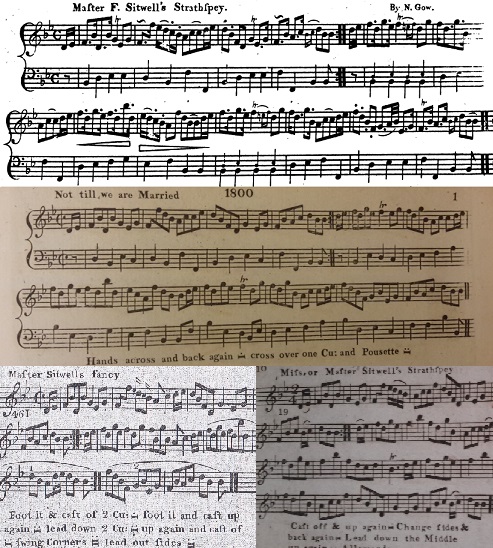

Master F. Sitwell's Strathspey / Not till we are Married... the festive scene concluded with Master Sitwell and The Isle of Sky, a medley(First Ball) The final dance of our first Abercorn ball was a medley consisting of Master Sitwell and also The Isle of Sky. We've studied the second of those tunes in a previous paper; it went on to be danced again as the opening tune of our second Abercorn ball, you might like to read more about it here.  Figure 10. Master F. Sitwell's Strathspey from Nathaniel Gow's c.1800 The Mad (or Poor) Boy (top), Not till we are Married from Cahusac's collection of 12 Country Dances for 1800 (middle), Master Sitwells fancy from the Preston collection of 24 Country Dances for 1801 (bottom, left), and Miss, or Master Sitwell's Strathspey from the Goulding collection of 24 Country Dances for 1800 (bottom, right). Middle image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, a.248.(10.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 10. Master F. Sitwell's Strathspey from Nathaniel Gow's c.1800 The Mad (or Poor) Boy (top), Not till we are Married from Cahusac's collection of 12 Country Dances for 1800 (middle), Master Sitwells fancy from the Preston collection of 24 Country Dances for 1801 (bottom, left), and Miss, or Master Sitwell's Strathspey from the Goulding collection of 24 Country Dances for 1800 (bottom, right). Middle image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, a.248.(10.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The tune named Master Sitwell was widely published in both Edinburgh and London between 1800 and 1802, the tune is readily identifiable. The origin of the tune is a little less obvious however. It was published twice in London and twice in Edinburgh in or shortly before the year 1800, under two very different names. It's difficult to prove which publication was issued first. Two editions were printed c.1800 in Edinburgh by Gow & Shepherd, in both cases the Edinburgh composition of the tune was credited to Nathaniel Gow; they were issued under the name The precise chronology of publication might be unclear but the Gow claim seems secure. Nathaniel Gow published another tune c.1800 in Edinburgh named Miss Sitwell's Strathspey, the c.1800 Goulding tune was named Miss, or Master Sitwell's Strathspey which strongly implies that Goulding was aware of the two similar names in use in Edinburgh, but that he was unaware that the Edinburgh tunes were actually quite different. He perhaps thought they were alternative titles for the same tune and reflected that uncertainty within his publication. If we assume that Goulding knowingly duplicated an Edinburgh tune, that just leaves the mystery of the Cahusac publication. My guess is that someone copied the Gow tune and presented it to Cahusac in London under the new (and cheeky) name of Not till we are Married, and that Cahusac printed it without knowing the true provenance of the tune. This is pure speculation of course, but I find it difficult to believe that Gow could have copied a London tune, renamed it (and also claimed composition credit for it), and then had his version copied in turn by Goulding, all within about a year.

The tune went on to be republished multiple times in or for the years 1801 and 1802. It appeared in Preston's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1801 as The tune was named after a young member of the Sitwell family. Francis Sitwell (c.1770-1813) was the younger brother of Sir Sitwell Sitwell (1769-1811). Francis was the owner of Barmoor Castle in Northumberland, he had married Anne Campbell (b.1773) in 1795; Anne was the daughter of Ilay Campbell, Lord Succoth (1734-1823) of Glasgow, a Senator of the College of Justice. Francis and Anne had at least five children together, including the young Master Francis Sitwell (1797-1865); the tune was named in tribute to this two or three year old boy who would eventually inherit Barmoor Castle. Francis Sitwell (senior) seems to have lived a troubled life, you can read more about the Sitwells of Barmoor here. The tune was danced at our Abercorn Ball of March 1801, then at Mrs Walker's Ball (Morning Post, 15th May 1801), at The Duchess of Chandos's Ball in 1802 (Morning Post, 26th April 1802), at The Duke of Cumberland's Military Ball (Morning Post, 19th May 1802), at Her Majesty's Ball (Lancaster Gazette, 28th May 1803), and at a Ramsgate ball of 1804 (Morning Post, 31st July 1804). It seems to have been popular for perhaps three years. We've animated suggested arrangements of Cahusac's 1800 version (see Figure 10), Dale's c.1802 version and of Wilson's 1809 version (to the music of Nathaniel Gow). For futher references to the tune, see also: Master F. Sitwell at The Traditional Tune Archive

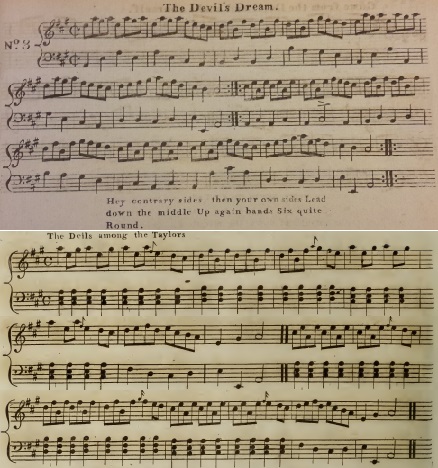

The Devil among the Taylors / The Devil's Dream... and at the conclusion of The Devil among the Taylors, supper was announced(Second Ball)  Figure 11. The Devils Dream from Martin Platts's Book 25 for the Year 1798 (top), and The Deils among the Taylors from Robert Petrie's c.1799 Third Collection of Strathspey Reels (below). Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.55.(1.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 11. The Devils Dream from Martin Platts's Book 25 for the Year 1798 (top), and The Deils among the Taylors from Robert Petrie's c.1799 Third Collection of Strathspey Reels (below). Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.55.(1.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The phrase

The tune we're interested in is readily identified, it was widely published in London between about 1800 and 1802. The first publication (that I can identify) of the tune was issued in London by Martin Platts in his Book 25 for the Year 1798 under the title

Subsequent publications of the same tune using Campbell's title include Preston's collection of 24 Country Dances for the year 1801, Cahusac's collection of 12 Country Dances for the year 1801, Milhouse's collection of 24 Country Dances for the year 1801 and Goulding's collection of 24 Country Dances for the year 1801. It can also be found in Goulding's c.1802 1st Number, Andrew's c.1802 1st Number, Davie's c.1802 1st Number and Dale's c.1802 1st Number. Thomas Wilson would go on to reference the tune in his 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore and again in his 1816 Companion to the Ballroom (this time under the name The tune was enjoyed at the balls of the nobility from at least 1800; examples include the Countess of Leicester's Ball (Caledonian Mercury, 27th March 1800), a Ball held by the Queen at Buckingham House (Ipswich Journal, 24th May 1800), a grand public breakfast hosted by the Duchess of Devonshire (Caledonian Mercury, 12th July 1800) and The Duchess of Gordon's Ball (Aberdeen Journal, 30th June 1800). It was also used at Lady Cornewall's grand ball (Morning Post, 13th April 1801), Lady Sykes's Ball (Morning Post, 5th May 1801), the Queen's Birthday Ball (Derby Mercury, 21st January 1802), Lady Cathcart's Ball (Morning Post, 12th March 1802), Mrs Robinson's ball (The Courier, 7th May 1802) and at yet another of the Queen's Balls (The Times, 16th June 1802). It was used at Mrs Townshend's ball (Morning Post, 7th May 1804) and a Ball at Brighton Castle (Morning Post, 15th August 1805). It seems to have remained popular over at least five years. We've animated suggested arrangements of Martin Platts's 1798 version (see Figure 11) and of Cahusac's 1801 version. For futher references to the tune, see also: Devil Among the Tailors (1) (The) at The Traditional Tune Archive

Mrs Garden of Troup's Strathspey... the ball recommenced with Mrs Gardiner a troop(Second Ball) The second Abercorn ball included a tune we've studied in a previous paper, you might like to read more about it there; it's another tune of Scottish origin that became popular in London around the turn of the century.

ConclusionWe've investigated a pair of early 19th century Balls in this paper, they were both hosted in London by the same fashionable and newly-wed couple just one week apart in 1801. As with our previous research papers we've found significant use of Scottish themed music and dance, we saw a similar programme at the 1799 Oatlands Fete and also at the two Carlton House royal balls that we studied from 1813. The Abercorn balls also included several Irish themed dances, this was particularly appropriate considering that the Abercorns were members of the Irish peerage; it's possible that their promotion of such tunes as Paddy O'Flanagan and Cary Owen will have directly contributed to the success of those tunes in London over the following few years. The Abercorns suffered the misfortune of having two periods of official Court mourning declared at around the date of their events. Many of their guests were aristocratic fashionables, they would have been subject to the formal dress rules that were in effect; the Balls nonetheless went ahead and were evidently successful, the Prince of Wales himself was present at the second event (potentially having been lured by the princely menu of the first ball). The dancing took place in a room painted to look like a Hop Ground, it was probably part of an Irish theme. The dancing consisted of Country Dances, together with an occasional Reel; this was a common arrangement for the date. If you'd like to recreate a society Ball of the early 19th Century, the tunes we've investigated in this paper would be very suitable to use. We'll leave the investigation there, but as always, do Contact Us if you have further information to share as we'd love to know more.

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved