| Return to Index |

|

Paper 41 Mrs Beaumont's Grand Balls, Part 1: 1807-1810Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 1st January 2020, Last Changed - 6th February 2024]

Mrs Diana Beaumont (1762-1831), wife of the Northumberland MP Colonel Thomas Beaumont (1758-1829), was one of the most consistent hostesses of the London season. She held grand balls in London that were commented upon by the newspapers over a period of perhaps 20 or more years. We'll consider what we can learn of those events over two separate research papers, this initial paper will focus on the years up to 1810. Mrs Beaumont was an immensely wealthy lady but she was also a figure of satirical fun, she was widely regarded as being a social climber or, to use novelist Maria Edgeworth's term, a  Figure 1 Mrs Diana Beaumont, courtesy of Engole.uk.

Figure 1 Mrs Diana Beaumont, courtesy of Engole.uk.

The tunes we'll be investigating further in this paper are:

Madame Diana Beaumont (1762-1831)Our Mrs Beaumont was born the illegitimate daughter of Sir Thomas Wentworth Blackett, 5th bt., of Hexham and Bretton (1726-1792). As an illegitimate child she could have little hope for advancement. Yet despite this comparatively inauspicious start she would go on to become one of the richest and most socially connected hostesses in the entire nation. Sir Thomas Wentworth, Diana's father, was the owner of significant estates near Wakefield in Yorkshire. His fortune grew further when he inherited the Blackett family's substantial lead mining interests in 1777, he changed his name from Wentworth to Wentworth Blackett as part of the inheritance process. He never married however and had no legitimate children, the question of how his estates would be distributed was of some significance. Diana (the future Mrs Beaumont) was the eldest of his approximately ten illegitimate children and it was she who would eventually be named as his primary heir (in trust for her newly born son Thomas Wentworth Beaumont (1792-1848)). She was probably born in 1762 (assuming her age as reported in her 1831 obituary was correct) and would be around 30 years of age when Sir Thomas died. In addition to the various Wentworth estates she would also, many years later, inherit still further estates in Northumberland when Sir Thomas' distant relation William Bosville (1745-1813) died in 1813; the Bosville's were reputed to be worth a further £5000 a year (Bath Chronicle, 4th March 1813) most of which was inherited by the Beaumonts. Diana married Colonel Thomas Beaumont in 1786 when she was approximately 24 years of age, he was another land owner from Yorkshire. Beaumont had briefly served in the army and would go on to serve as a Member of Parliament for Northumberland. Diana's father invited Beaumont to witness the signing of his Will in 1790, this Will would leave relatively little to Diana. What happened next is uncertain but two years later the Will was substantially rewritten to Diana's benefit. You can read more of the details of this suspicious affair on the Engole website. The result of the well-timed change caused Diana to inherit most of her father's estate, she went on to manage her business interests personally. She would gain a reputation, at least amongst her neighbours in Yorkshire, for being a tough and opinionated lady.

Figure 2 The English Ladies Dandy Toy, 1818 (top) and a detail from An Affecting Scene in Hyde Park, 1813 (below). Top image courtesy of the British Museum, bottom image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 2 The English Ladies Dandy Toy, 1818 (top) and a detail from An Affecting Scene in Hyde Park, 1813 (below). Top image courtesy of the British Museum, bottom image courtesy of the British Museum.

probably one of the richest commoners in England. It is perhaps from this reference that Beaumont-junior's reputation for being the richest commoner in Englandwas subsequently derived. One of the newspapers in 1814 estimated the Beaumont's annual income to be greater than £100,000, this was an unimaginably large sum at the time (Morning Post, 10th January 1814); that's ten times the annual income attributed to the fictional Mr Darcy! Another newspaper would estimate in 1815 that the Beaumont's were responsible for over a third of the entire lead mining production in Britain (Durham Country Advertiser, 8th April 1815).

Colonel Beaumont was reputed to be a weak politician who was primarily motivated by opportunities to secure for himself a peerage (a goal that he pursued without success); one M.P. was reported to have complained that: They were very well connected. The social commentators of the period could hardly ignore them. Mary Russell Mitford (1787-1855) wrote in a letter from 1806: Colonel Beaumont is generally supposed to be extremely weak; and I had heard so much of him, that I expected to see at least as silly a man as Matthew Robinson; but I sat next him at dinner, and he conducted himself with infinite propriety, and great attention and politeness; yet, when away from Mrs Beaumont, he is (they say) quite foolish, and owes everything to her influence with him. They live in immense style at the Abbey; thirty or forty persons frequently dine there; no servants but their own admitted; and there is constantly a footman behind every chair.

The socialite Mrs Calvert (1767-1859) wrote of Mrs Beaumont in her journal in an entry dated December 23rd 1805:

The novelist Maria Edgeworth (1768-1849) published a short story named Manoeuvring in 1809 which featured a widow named Mrs Beaumont; Edgeworth's Eugenia Beaumont had also been married to a Colonel Beaumont and was a prominent social climber: Another commentary can be found in the memoirs and Recollections of Captain Gronow. He wrote of our Mrs Beaumont: There are probably many persons who remember this lady. She was reported to have been of low origin, but inheriting vast estates in the north, and having married a colonel of militia, who became member for the county where her large estates lay, she became one of the leaders of the fashionable world in 1812. From that time to 1820, it was impossible, during the London season, to walk from St James's Street to Hyde Park at a certain hour in the afternoon, without seeing her and her daughters in her large yellow landau. Her style of living was most luxurious and full of ostentation. Her preference of a nobleman before a gentleman of no title was shown in a manner that was perfectly ridiculous, and evinced a great want of good sense and tact. Herfêteswere thronged with thegrand monde, and her system of excluding all but persons of rank amused the fashionable world: even men of talent and good family rarely got theentréeof her saloons. Mrs Beaumont had the good luck to inherit a fortune, and the good sense to manage it, but she clearly evoked jealousy from those around her. Her neighbours in Yorkshire were reported to mockingly name her Madame Beaumont in reference to her pretentious status as a grand-dame of London fashion (they may of course have been genuinely in awe of her). The truth no doubt is more complicated, her guests at Portman Square included members of the royal family and the highest ranks of the nation's nobility, they presumably saw something of value in her. The Colonel's influence in Parliament may have been inconsequential, but their wealth and the esteem it afforded them wasn't.

Note: The two images in Figure 2 are not believed to be of Mrs Beaumont. It's nonetheless curious that the lady in the top image shares her features and is depicted manipulating a toy dandy; the excitement around the yellow carriage in Hyde Park from the bottom image resonates with Captain Gronow's description of her. It's plausible that either image may have been intended to be recognised as a caricature of our Mrs Beaumont.

Mrs Beaumont's Earlier BallsPassing references to the Beaumont Balls exist from the late 1790s, the more detailed accounts appear a little later. The early references may be underwhelming but they are representative of the reporting that might generally be expected of such events at these dates. Amongst the early references include:  Figure 3 The northern side of Portman Square, c.1810. Image Courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 3 The northern side of Portman Square, c.1810. Image Courtesy of the British Museum.

Mrs Beaumont's juvenile Ball, June 1807The following text was printed in the Morning Post newspaper for 4th June 1807, dance references are in bold: On Tuesday evening the Lady of Colonel Beaumont gave an elegant children's ball, at the family residence in Portman-square. This unique little fete was attended by many of the first leading personages in the circles of fashion. The house, which is extremely elegant, particularly in its internal decorations, was even more than usually attractive on the above evening. The illuminated apartments shone with unrivalled brilliantcy about nine o'clock. The ball was opened previous to that hour with The Nameless. Miss Beaumont led off with a young Gentleman, whose name we could not learn. The dancing continued until twelve o'clock, when the music ceased, and the company retired to the supper rooms, the tables in which were abundantly stored with every delicacy the season produces. This juvenile ball was hosted in the evening rather than over-night, the guests were presumably the children of the nobility. The only named tune was, a little ironically, named The Nameless, we'll consider it further below. The leading lady was the 11 year old Miss Diana Beaumont (the Beaumont's oldest daughter), though with further irony her partner's name also remains unknown. Perhaps the intention was that the Beaumont children would meet and ultimately grow up with friends from amongst the nobility; a juvenile ball was an event held in a similar style to an adult ball but conducted earlier in the evening and (presumably) with less seriousness attached. Figure 4 shows children dancing at some kind of organised rural event, the unknown artist depicted what might have been a circle dance around a goose together with a couple dance in the foreground. There's no reason to think that the Beaumont's juvenile ball would have anything in common with the image. The Beaumonts would go on to host further such balls over the following few years.  Figure 4 Juvenile Entertainment c.1807.

Figure 4 Juvenile Entertainment c.1807. A large musical party passing their time in perfect harmony. NB, a little Goose in the center of the ring joins in with the young party in company. This woodcut image derives from an anonymously printed piece of music of uncertain date which is simply titled Gavot.

Mrs Beaumont's Grand Ball and Supper, April 1809The following text was printed in The Globe newspaper for the 17th April 1809, dance references are in bold: This Lady gave, on Friday, a splendid entertainment, at her elegant house, in Portman-square,[lacuna]was attended by upwards of five hundred fashionables. The arrangements for the evening displayed the greatest taste and elegance. The grand hall and stair-case were brilliantly lighted, and the servants wore their state liveries. The Ball room, which, in dimensions, as well as in elegance and richness of the furniture, is most superb, was lighted by a large diamond cut glass chandelier, elliptic stands, and[three Duchesses, one Marchioness, one Countess, two Earls, five Lords, an Archbishop, fifteen Ladies, seven Sirs, five Messrs, three Mistresses and seven Misses].or-molubranches, with wax lights. The floor was tastefully chalked in devices. In the other apartments card-tables were set out. The supper rooms were brilliant; the tables were laid for three hundred persons, and decorated in a most tasteful manner: grottos, temples, and bouquets were places round. In the centre of the table was a superb gold plateau, with six gold branches, for lights; the service was of silver. At the top of the table wasBritannia, supporting the bust of the lateLord Nelson, with the Lion at her feet, underneath theVictory, with the mottosTrafalgar,Copenhagen, andAboukir; opposite wasNeptune, the whole executed in transparent jelly, which had a most beautiful effect, and did great credit to the ingenuity of Mr Read, who regulated this grand entertainment. At ten o'clock the ball was opened by Lord Sunderland and Miss Diana Beaumont, to the favourite dance of Michael Wiggins - the music under the direction of Mr Gow. After this dance, which went off with great spirit, the two Miss Beaumonts, who were pupils of Mr Vestris, danced a Boleros, with great correctness; they were loudly applauded by the company. The Fairy Dance then followed; the third dance Lord Cathcart, and La Boulangere concluded the dancing, when supper was announced at one o'clock. It consisted of every delicacy of the season - soups of every description, and a most superb desert, with the choicest wines, graced the festive board. At half past two the company returned to the ball-room, and continued dancing until day light; when they broke up, highly gratified with the attention of their host and hostess. Among the company were This was the first of the Beaumont Balls to be rewarded with a non-trivial description of the dancing, we'll consider the named tunes and dances further below. The music was led by the ever popular Gow band, presumably under John Gow. We're informed of the significant effort that was invested into the lighting, the menu and floor chalking; this event was evidently a first class entertainment.

Mrs Beaumont's Ball, April 1810The following text is from the Morning Post newspaper for 28th April 1810, dance references are in bold: The Lady of Col. Beaumont gave a Ball and Supper on Thursday night, at the family residence in Portman-square. This was the first fashionable party for the season. Much taste and elegance were displayed in the decorations, and lighting up of the apartments. The dancing commenced at eleven o'clock, led off by the Hon. Mr McDonald, and the Duchess of Manchester, to the popular tune of the Fairy Revels. About fifteen couple danced. The supper was served up at half past one o'clock; about three the company retired. Previously to the Ball, anAmateurConcert was given, at which Messrs Dawkins, Montgomery, &c. assisted, Reels and Strathspeys were danced by the Duchess of Manchester, Lord Saltoun, Mrs Frazer, Mr Montgomery.  Figure 5 A fruit bowl as seen in the BBC's 2013 Pride and Prejudice: Having a Ball, perhaps in a similar style to those from the Beaumont Ball.

Figure 5 A fruit bowl as seen in the BBC's 2013 Pride and Prejudice: Having a Ball, perhaps in a similar style to those from the Beaumont Ball.

We're informed that this event was preceded with an amateur concert. Perhaps some of the guests (or their children) were invited to entertain the company.

Mrs Beaumont's Ball, May 1810The final ball we'll consider in this paper was held approximately a week after the previous example, the following text is from the Morning Post from the 3rd May 1810, dance references are in bold: Mrs Beaumont's Ball, Given on Monday night, was remarkable for its splendour and taste. The superb service of plate displayed on the supper-tables astonished even those who are accustomed to view such magnificent objects daily. There were no less than 500 dishes used, the whole being composed of massy silver, with agadroonedge, and exhibited at the same time with other suitable articles the effect may be more easily conceived than described. The early part of the night was devoted to a Children's Ball; the latter ended at ten minutes before 12 o'clock; half an hour after the regular Ball commenced. Lord Kinnoul led off Prime of Life, with the Hon. Miss Beaumont. Among the couples were: Hon Mr James McDonald and Lady Saltoun, Mr Frazer and Miss Mildmay, Captain Warrender and Lady Harriet Drummond, Mr Wynne and Miss Spencer Stanhope, Mr F Macdonald and Miss Frazer, Mr Stephen and Miss Milbanke. It's perhaps notable that the guests at this ball, contrary to the assertions of Captain Gronow above, included several untitled gentlemen. It's also of note that one of the guests was Miss Spencer Stanhope of Cannon Hall in Yorkshire, a close neighbour of the Beaumonts when at home in the shires. This particular event combined both a juvenile ball and a regular ball one after the other, this may have been a common practice but this is one of the rare occasions where the concept is explicitly described. We'll now consider the named tunes and dances from these various balls.  Figure 6 The Nameless from William Campbell's c.1808 23rd Book (above) and from Button & Whitaker's c.1808 8th Number (below). Upper image © National Library of Scotland.

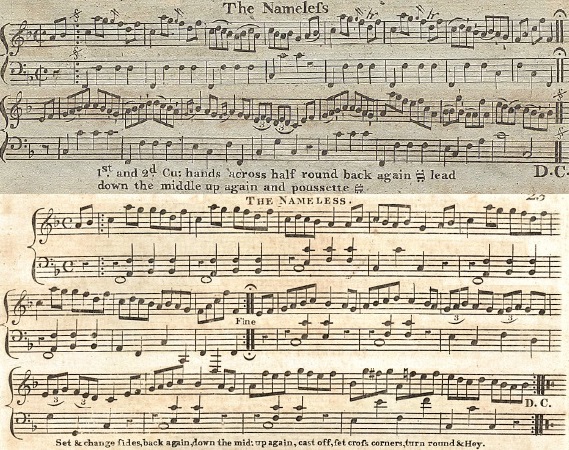

Figure 6 The Nameless from William Campbell's c.1808 23rd Book (above) and from Button & Whitaker's c.1808 8th Number (below). Upper image © National Library of Scotland.

The NamelessThe ball was opened previous to that hour with The Nameless. Miss Beaumont led off with a young Gentleman, whose name we could not learn.(1807 juvenile Ball) This curiously named tune was widely published in London between about 1807 and 1809, it was briefly a favourite. At least two different tunes were published under this same name, although many others were of course published without names; of the two one was far more popular with the London music publishers and must surely have been the tune from our ball. Miss Diana Beaumont, who led off the dance, was the eldest of the Beaumont's daughters, she was 11 years old at the date of this event; her unnamed partner was probably of a similar age.

Our tune was widely published and consistently named as

The tune was well known for perhaps two years but it did not feature often at the balls of the aristocracy. I only know of one further use of the tune in addition to that of our ball, that was at Mrs Boehm's Ball in 1807; the Boehm ball was held shortly before our event (Morning Post, 23rd May 1807), The Nameless initially proved to be popular with her guests, one of whom may even have been the composer: Nathaniel Gow in his collection of The Favourite Dances of 1810 identified the composer of this tune as being Lady Mildmay, previously Miss Charlotte Bouverie. Charlotte would marry Sir Henry St John-Mildmay (1787-1848) in 1809, she died from complications of childbirth the following year. We've animated suggested arrangements of Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 variant of the tune, of Skillern & Challoner's c.1807 version, of William Campbell's c.1808 version (see Figure 6) and of Button & Whitaker's c.1808 version (see Figure 6).

Michael WigginsAt ten o'clock the ball was opened by Lord Sunderland and Miss Diana Beaumont, to the favourite dance of Michael Wiggins(1809 Ball) This tune was the opening dance for the 1809 ball, it was led off by the now 13 year old Miss Beaumont and the 15 year old George Spencer-Churchill (1793-1857) (later the 6th Duke of Marlborough). It was quite normal for a hostess to have her daughter lead off the first dance of a Ball though Miss Beaumont was unusually young for the honour. This may have been her first opportunity to dance at an adult Ball, attended as it was by Duchesses, Earls and an Archbishop; her formal introduction to high society would follow in 1813 (Morning Post, 20th March 1813) when she was 17 years old.  Figure 7 Michael Wiggins in James Platts's 1809 11th Number (top), in Dale's c.1809 16th Number (middle) and in Goulding's 24 Country Dances for 1810 (bottom, right). Also the first two verses of the 1808 Michael Wiggins in Debt (bottom, left). Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(10.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 7 Michael Wiggins in James Platts's 1809 11th Number (top), in Dale's c.1809 16th Number (middle) and in Goulding's 24 Country Dances for 1810 (bottom, right). Also the first two verses of the 1808 Michael Wiggins in Debt (bottom, left). Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(10.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The tune is easily identified, it was widely published in London in both 1809 and 1810. The name Aside: I'm aware that several works exist that include this tune and have estimated publication dates prior to 1809. Several authorities (for example) wrongly attribute the tune to the Preston collection of Country Dances for 1801 - it was actually published in the Preston collection of 24 Country Dances for 1810. I suspect that the estimated dates are incorrect, the overwhelming weight of evidence points to the tune emerging in 1809.The tune was evidently popular, most of the London music shops issued versions over the following year or two. The precise chronology can't be established but examples include: Wheatstone's 1809 19th Number, Wheatstone & Voigt's 1809 4th Book, Dale's c.1809 16th Number (see Figure 7, middle), Goulding's 24 Country Dances for 1810 (see Figure 7, bottom), Bland & Weller's 24 Country Dances for 1810, Fentum's 24 Country Dances for 1810, Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1810, Wheatstone's 24 Country Dances for 1810, Monzani's c.1810 12th Number, Walker's c.1810 24th Number, Andrew's c.1810 23rd Number, Davie's c.1810 21st Number and Button & Whitaker's 1813 21st Number. The tune would also be referenced in both Thomas Wilson's Treasures of Terpsichore for 1810 and his Treasures of Terpsichore for 1811, and also in Edward Payne's 1814 A New Companion to the Ball Room. It would also be published in Edinburgh by Nathaniel Gow in his 1810 Lady Matilda Bruce's Reel.

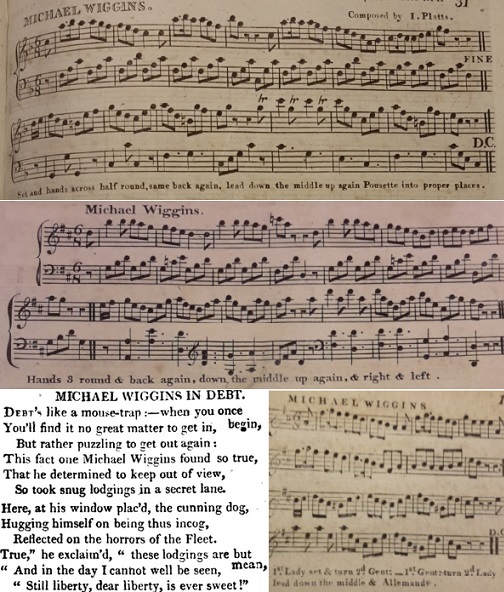

The name Our tune was a favourite in the fashionable circles of 1809. In addition to the Beaumont Ball it was also enjoyed at Mrs Leigh's Ball and Supper (Morning Post, 24th May 1809), at Lord Temple's Fete at Dover (Kentish Gazette, 6th October 1809) and at Hon Mrs Harvey's Ball in Sussex (Morning Post, 26th December 1809). Ordinarily the story might end there with the tune having lost its fashionable credentials by about 1811 or 1812. But in 1815 James Platts was accused of stealing copyrighted tunes owned by Button & Whitaker, he retaliated with a counter-claim of his own involving this tune. We've investigated these legal disputes in another paper, you might like to follow the link to read more. It seems likely that Platts really was the composer of the tune. The music publishers of 1809 tended not to consider copyright as an issue for Country Dance tunes, the industry had always shared. By 1815 that convention had broken down, Platts sued both Button & Whitaker and Charles Wheatstone over alleged copyright violations, you can read more in our paper covering their disputes. We've animated suggested arrangements of James Platts's 1809 version of the tune (see Figure 7, top), of Wheatstone & Voigt's 1809 version and of Dale's c.1809 version (see Figure 7, middle). For futher references to the tune, see also: Michael Wiggins (2) at The Traditional Tune Archive  Figure 8 The much admired Boleros, as danced by Monsr Vestris & Sigra Angiolini in the favorite Spanish Divertisment, from Skillern & Challoner's c.1810 12th Number. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.cc ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 8 The much admired Boleros, as danced by Monsr Vestris & Sigra Angiolini in the favorite Spanish Divertisment, from Skillern & Challoner's c.1810 12th Number. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.cc ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Bolerosthe two Miss Beaumonts, who were pupils of Mr Vestris, danced a Boleros, with great correctness; they were loudly applauded by the company.(1809 Ball) This dance was a performance by the Beaumont's two oldest daughters, the 13 year old Miss Diana Beaumont (who had led-off the first dance) and the 11 year old Miss Marianne Beaumont (her name is sometimes given as Miss Mary Anne Beaumont). They were evidently pupils of one of the celebrated Vestris family of dancers, presumably of Armand Vestris who had settled in London in January 1809. The Vestris family, for three generations, had been principal dancers of the Parisian stage; their name was well known in London, the Vestris Gavotte, for example, had been a celebrated stage dance in London since around 1807 although it probably dated back to the 1790s. Armand Vestris performed his Boleros on stage with Miss Angiolini in James Harvey D'Egville's opera Don Quichotte, ou les noces de Gamache in early 1809, it was presumably this same dance that he'd been employed to teach to the Beaumont girls. His tuition can't have been cheap! The English nobility often employed stage performers to teach dancing to their children, employing the most celebrated dancer in London must have been quite a status symbol. We're assured that the assembled company were sufficiently polite to loudly applaud the performance. The Vestris Bolero is sometimes described as being a Fandango dance, it involved the use of castanets during the performance. We've described how James Platts promoted the use of castanets for social dancing from 1804 in another paper, he saw significant new interest in the instrument around 1809, a date at which they (presumably) achieved a degree of fashionable popularity. We've also written of the Boleros as a social dance elsewhere. Figure 8 shows the music for the Vestris Bolero as published by Skillern & Challoner in their c.1810 12th Number. We've noted a similar performance by the nine year old Augustus Stanhope of Mrs Wybrow's Hornpipe at a society Ball of 1803; inviting favoured children to demonstrate a popular stage dance may have been a common practice at a ball.

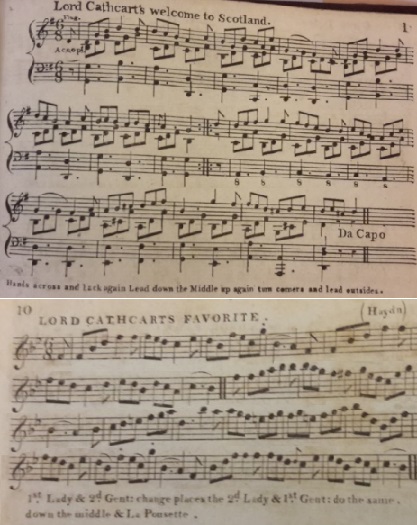

Largo's Fairy DanceThe Fairy Dance then followed(1809 Ball) This popular tune is one we've studied in a previous paper, together with the conflicting claims over who composed it. It was widely danced from around 1807, you might like to refer to our previous paper for further information. For futher references to the tune, see also: Fairy Dance at The Traditional Tune Archive  Figure 9 Lord Cathcart's welcome to Scotland from Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 1st Book (top), and Lord Cathcart's Favorite from Goulding & Co's 24 Country Dances for the Year 1811 (below). Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.64. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 9 Lord Cathcart's welcome to Scotland from Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 1st Book (top), and Lord Cathcart's Favorite from Goulding & Co's 24 Country Dances for the Year 1811 (below). Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.64. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Lord Cathcart's Welcome to Scotland / Lord Cathcart / Lord Cathcart's Favoritethe third dance Lord Cathcart(1809 Ball) This tune is readily identified, it was widely published in London between about 1808 and 1811. Several other tunes with similar names also circulated, Goulding & Co alone published Lord Cathcart's Welcome to Scotland, Lord Cathcart, Lord Cathcart's Whim, Lord Cathcart's Reel, Lord Cathcart's Favorite and Lady Cathcart over this four year period; but the vast bulk of the London publications all issued the same tune, it was clearly the favourite of the family. The dedicatee was William Cathcart (1755-1843), 10th Lord Cathcart, he would subsequently be made the 1st Earl of Cathcart. He was a career soldier who's biggest success came in 1807 when he captured the Danish fleet at the Battle of Copenhagen. The success of our tune in London was presumably a recognition of Cathcart's victory. The tune predates that victory however and therein lies some confusion.

The earliest publication of the tune under the Cathcart name that I can find dates to either 1806 or 1807 where it can be found in Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 1st Book (see Figure 9, top). Dating this book is a little complicated, we've discussed the issues in another paper; at least two different editions of this first book exist, the earlier printing uses the name Lord Cathcart's Welcome to Scotland while the later simplifies it to just Lord Cathcart. Lord Cathcart did indeed return to Scotland after his Danish victory, but not until after Wheatstone had publicly advertised availability of what was either his first or second book (Morning Post, 7th October 1807). The

Many London publishers issued versions of the tune but only one of them identified a composer; the version published by Goulding & Co in their 24 Country Dances for the Year 1811 notes that the tune was composed by Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) (see Figure 9, bottom); they had previsouly issued the tune at least three times without identifying the composer, it can be found in their c.1808 12th Number as The origins of the tune may be a little murky but the success of the tune isn't; after the initial c.1806 publication by Wheatstone & Voigt and the c.1808 republication by Goulding & Co. it would go on to be published by: Clementi & Co in their c.1809 6th Number, Andrews in their c.1809 9th Number, Monzani in his c.1809 10th Number, Walker in his c.1809 20th Number, Dale in his c.1809 14th Number, Button & Whitaker in their c.1809 11th Number, Skillern & Challoner in their c.1809 8th Number, James Platts in his c.1809 9th Number, Halliday & Co. in their c.1809 1st Number, Ball in his c.1809 1st Number, Fentum in his 24 Country Dances for 1810, Preston in his 24 Country Dances for 1810 and Wheatstone once again in his 24 Country Dances for 1810. It would also be named in Thomas Wilson's 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore and in Edward Payne's 1814 A New Companion to the Ball Room. The tune was widely published but seems not to have featured amongst the descriptions of society balls other than our 1809 Beaumont Ball; a tune named Lord Cathcart's Reel was danced at an Irish Ball in 1810 (Saunders's News-Letter, 22nd August 1810), but that was most probably a different tune. We've animated suggested arrangements of Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 version of the tune (see Figure 9) and also of Skillern & Challoner's 1809 version. For futher references to the tune, see also: Lord Cathcart at The Traditional Tune Archive  Figure 10 La Boulanger from Francis Werner's 1780 13th Book. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.55.c.(2.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 10 La Boulanger from Francis Werner's 1780 13th Book. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.55.c.(2.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

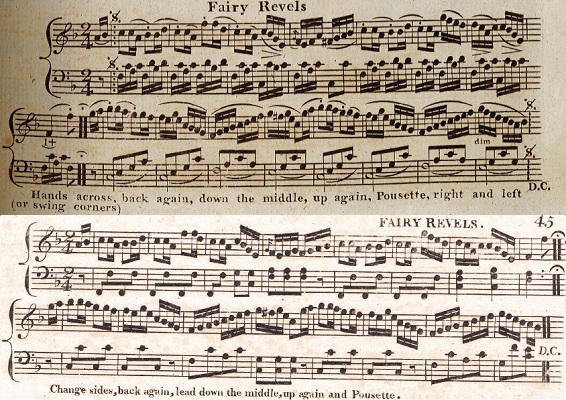

Le Boulangerand La Boulangere concluded the dancing, when supper was announced at one o'clock.(1809 Ball)

Le Boulanger, La Boulanger or La Boulangere is an example of a

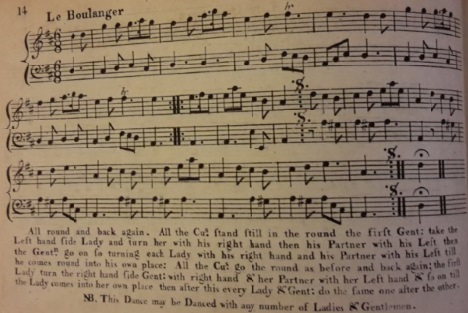

The Boulanger is sometimes described as a Campbell wasn't the first music seller to arrange music for this dance, nor was he the last. It had previously been published in Francis Werner's 1780 13th Book (see Figure 10) and probably also in Thomas Budd's 1780 8th Book. It would go on to be published in Skillern & Straight's 12 Country Dances for 1792 and also in Dale's c.1804 4th Number. It was also published in Edinburgh in Niel Gow's Third Collection of Strathspey Reels &c. under the name The Boolonzie. Werner's 1780 music for Le Boulanger in Figure 10 is quite different to that of Campbell's c.1789 version, it's perhaps rather better suited to the dance than that of the later publication. We've studied Campbell's arrangement of the music in a previous paper. Werner's second strain of music is 10 bars in length (which is reminiscent of the La Batteuse French Country Dance that we studied in another paper), with the opportunity to repeat 8 bars as many times as are needed given the number of dancers in the circle. The repeating section consists of 4 bars of music that are played twice through. If the musicians know how many couples are in the circle they can play exactly four bars per couple (plus the original two), thereby allowing the tune to scale gracefully with the number of dancers. I suspect this was the intended arrangement, rather than requiring a mad scramble from the dancers to get through the figure before the musicians moved on! As with many social dances of the period, the best experience is achieved when skilled musicians adapt the music to fit the needs of the dancers in-situ. Modern dancers who recreate these dances to recorded music can struggle to experience them as they were (probably) intended to be danced.  Figure 11 Fairy Revels from Skillern & Challoner's c.1810 11th Book (top) and from Hodsoll's c.1811 15th Number (below). Top image © VWML, EFDSS.

Figure 11 Fairy Revels from Skillern & Challoner's c.1810 11th Book (top) and from Hodsoll's c.1811 15th Number (below). Top image © VWML, EFDSS.

We've animated an arrangement of Francis Werner's 1780 version of the dance (see Figure 10). For futher references to the tune, see also: Boulanger (La) at The Traditional Tune Archive

Fairy RevelsThe dancing commenced at eleven o'clock, led off by the Hon. Mr McDonald, and the Duchess of Manchester, to the popular tune of the Fairy Revels. About fifteen couple danced.(April 1810 Ball) This dance was led off by Susan Montagu (1774-1828), third daughter of the Duke and Duchess of Gordon and wife of the 5th Duke of Manchester; her partner was James MacDonald (1784-1832).

At least five different tunes named Fairy Revels were in circulation near the start of the 19th century; three were published c.1803 (by Fentum, Bland & Weller and Preston), one c.1810 and another in 1812 (by James Platts). The c.1810 tune was published by several of London's music shops whereas the other four are only known from a single source, there can be little doubt that the c.1810 tune was the one danced at our Ball. The precise chronology of publication can't be established but the earliest publication of our tune might have been in Skillern & Challoner's c.1810 11th Book (see Figure 11); this publication includes the noteworthy figure

The name

It's not clear whether or not our tune was derived from the Burletta, I can't find any similarity in the scores though it's plausible that they're linked. The tune seems not to have been danced elsewhere either, the Beaumont ball is the only event I can find to have positively featured our tune; our correspondent asserted that it was a We've animated a suggested arrangement of Skillern & Challoner's c.1810 version of the dance (see Figure 11), and of Wheatstone & Voigt's 1811 version of the dance.

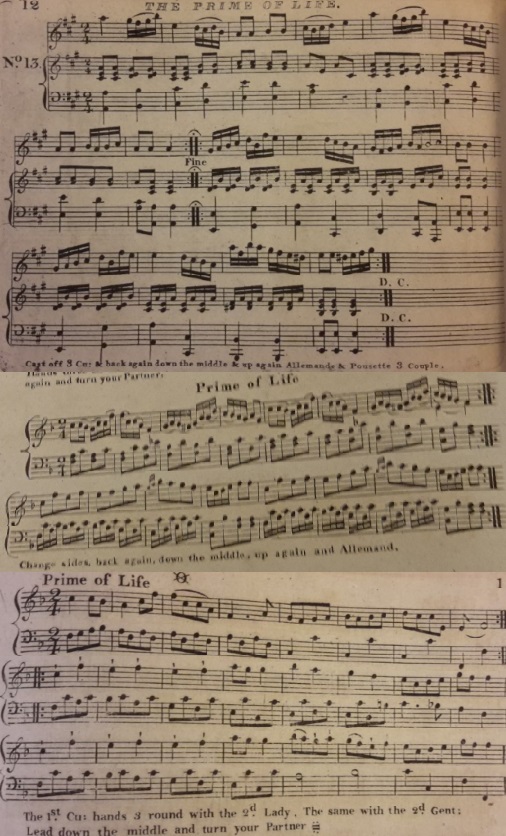

Figure 12 The Prime of Life from Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1808 3rd Book (top), from Skillern & Challoner's c.1809 8th Number (middle), and from William Campbell's c.1809 24th Book (bottom). Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.64. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED; bottom image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.96. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 12 The Prime of Life from Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1808 3rd Book (top), from Skillern & Challoner's c.1809 8th Number (middle), and from William Campbell's c.1809 24th Book (bottom). Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.64. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED; bottom image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.96. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Reels and StrathspeysReels and Strathspeys were danced by the Duchess of Manchester, Lord Saltoun, Mrs Frazer, Mr Montgomery.(April 1810 Ball)

Our third ball concluded with

The Prime of LifeLord Kinnoul led off Prime of Life, with the Hon. Miss Beaumont.(May 1810 Ball) This dance was led off by the now 14 year old Miss Diana Beaumont and her partner Thomas Hay-Drummond (1785-1866) the 11th Earl of Kinnoull.

The tune that had been selected was one that had circulated in fashionable society since around the year 1808; an early reference to the tune being danced involved The Duchess of Bolton's Ball (Morning Post, 13th July 1808) where

Several different tunes were published in London in 1809 named the

In practice we really only have two major tunes, the second being available in both long and short measure arrangements. Our third tune lends itself to an interpretation that halves the tempo and strains of the second tune. We've employed a strategy in previous papers to discover the most popular of a set of similarly named tunes of Scottish origin. This strategy involved reviewing the London tune collections to see which tunes were issued there, if a tune was popular then the London music shops would publish that version; on this occasion we can reverse the strategy. Gow & Shepherd published a version of The Prime of Life as part of their c.1810 Morgiana publication in Edinburgh; their publication is almost certain to contain the tune that was danced at the Perthshire Hunt Ball of 1809, and by extension be the tune that was known to the London aristocracy. The version that they published was our third candidate. This removes most reasonable doubt, the third tune was the popular arrangement.

Morgiana in IrelandAt seven in the morning, Morgiana in Ireland, a non-descript kind of dance (quite new), being in three parts, an Irish jig, and the fourth a waltz figure, afforded a fund of merriment to all the amateurs present.(May 1810 Ball) This tune is a member of a family of tunes that shared a somewhat similar development with that of the Michael Wiggins family we investigated above. Numerous different tunes were published between about 1808 and 1815, examples include Morgiana, Morgiana in Ireland, Morgiana in Spain, Morgiana in France, Morgiana in Paris, Morgiana in Russia, Morgiana in Portugal, Morgiana in Scotland, Morgiana in the Park, Morgiana in Salamanca, Morgiana at Richmond and Morgiana's Return from Ireland. The first three of this family were very widely published, Morgiana was popular c.1809, Morgiana in Ireland c.1810 and Morgiana in Spain c.1812. A curiosity of this family of tunes is that the differently named variants generally referred to the same tune across publishers; for example, all of the publishers who printed Morgiana in Ireland consistently used the name for the same tune (unlike the pattern we identified when investigating the Prime of Life above).

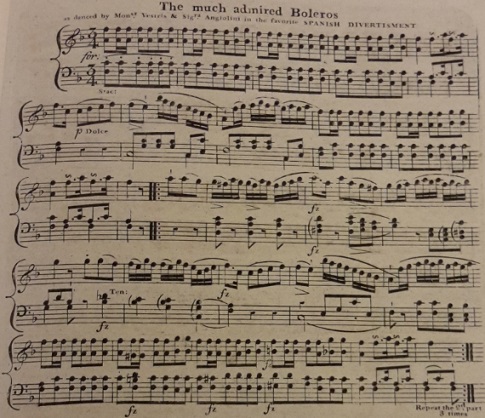

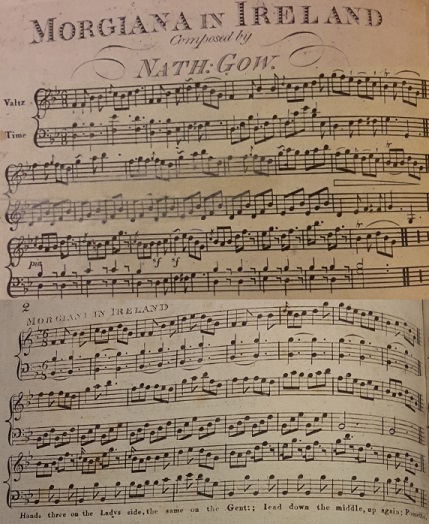

Figure 13 Morgiana in Ireland from Nathaniel Gow's c.1810 publication of the same name (top), and from James Platts's c.1809 13th Number (below). Bottom image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(10.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 13 Morgiana in Ireland from Nathaniel Gow's c.1810 publication of the same name (top), and from James Platts's c.1809 13th Number (below). Bottom image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(10.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The name Morgiana derives from a character in Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, itself a story from the 1001 Arabian Nights; Morgiana is a slave girl in the story who saves Ali's life. A dramatic performance with music by Michael Kelly had been adapted for the Drury Lane stage in late 1804 (Morning Post, 28th December 1804) and was performed from mid 1806 (Morning Post, 7th April 1806). The initial Morgiana tune may have been derived from Kelly's score (though Nathaniel Gow identified the composer in his collection of The Favourite Dances of 1810 as Miss Charlotte Bouverie, later Lady Mildmay, the same lady who composed The Nameless). The Kelly production was on a particularly lavish scale with keen public interest in the preparations for over a year; for example, The Courier for the 20th July 1805 wrote that Our ball featured the Morgiana in Ireland tune; a precise chronology of publication in London can't be established, but examples include: James Platts's c.1809 13th Number (see Figure 13), Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1809 4th Book, Dale's c.1809 16th Number, Skillern & Challoner's c.1810 10th Number, Wheatstone's c.1810 20th Number, Walker's c.1810 24th Number, Monzani's c.1810 15th Number, Goulding's c.1810 17th Number, Hodsoll's 12 Country Dances for 1810, Button & Whitaker's 1811 15th Number, Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1811, Fentum's 24 Country Dances for 1811 and Goulding's 24 Country Dances for 1811.

The tune was also published in Edinburgh by Nathaniel Gow c.1810, Gow's publication is of particular interest as he explicitly claimed to be the composer of the tune (see Figure 13). He may very well have been the composer, but if so the tune seems to have circulated in London without a composition credit prior to Gow having claimed it in Edinburgh. It would also be published by Archibald Duff of Aberdeen in his 1812 Part First of A Choice Selection of Minuets, Favourite Airs, Hornpipes, Waltzs &c., Duff added the musical direction

The correspondent from our ball described the tune as being I'm only aware of a pair of society balls that featured this tune; the other, also from 1810, was Lord Sydney's Ball and Supper (Morning Post, 4th May 1810). We've animated suggested arrangements of James Platts's c.1809 version of the dance (see Figure 13), of Dale's c.1809 version and of Skillern & Challoner's 1810 version. For futher references to the tune, see also: Morgiana in Ireland at The Traditional Tune Archive

ConclusionWe've studied several balls in this paper that were held by the same hostess over several years, we'll go on to study more of them in a subsequent paper. We know the names of some of the dances that were enjoyed at these events, most were moderately well known Country Dancing tunes that were in fashion at the date of the events. The programmes included display dances such as the Boleros and French Country Dances such as the Boulanger. The hostess, Mrs Beaumont, often proceeded her events with a juvenile ball for the children. This would be followed by a grand ball for the parents that would continue throughout the night. Mrs Beaumont, as was the case with most hostesses, would usually invite her daughter to lead off the first dance. Her children might also be invited to perform a display dance to the assembled company. One curiosity of the Beaumont balls are the relative shortage of Scottish themed dances. Some tunes and dances of Scottish origin were enjoyed, but the majority were not known to be Scottish (unlike most of the other balls that we've studied in our recent research papers). The tunes would, in most cases, go on to be published in Edinburgh by Nathaniel Gow (and others) but their origins lie elsewhere. Many of the tunes appear to be of English origin, all were popular amongst London's social elites. We'll leave this investigation here but will return to this same subject for Part 2. If you have more information to share, do please Contact Us as we'd love to know more.

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved