| Return to Index |

|

Paper 43 The Carlton House Balls, 1811-1816Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 10th April 2020, Last Changed - 12th February 2024]

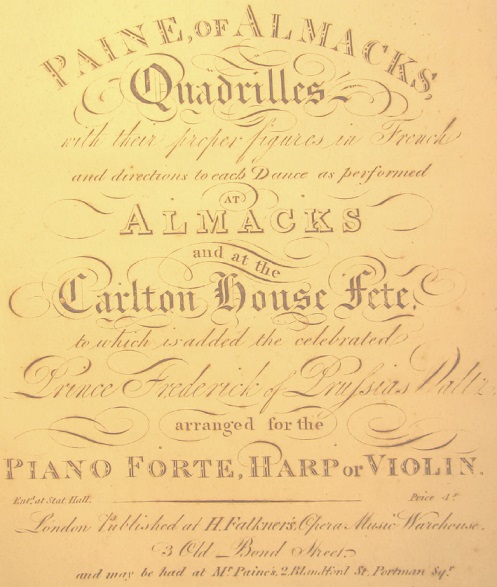

Carlton House in London was the home of the Prince of Wales throughout the period at which he was the Prince Regent. It hosted numerous Balls, Galas and Fetes during the Regency, events attended by the fashionable elite. This paper will consider the dancing across a number of those events, in so doing we will attempt to solve a little mystery that has puzzled me up until now, a mystery that involves the introduction of the Quadrille dance in London. The core of the mystery involves the 1816 publication of James Paine's First Set of Quadrilles; the cover of his publication indicated that they were danced In addition to studying the various Carlton House Balls, we will also study the following tunes and dances in this paper:  Figure 1. James Paine

Figure 1. James Paine of Almacks's1816 Quadrilles, as danced at the Carlton House Fete.

The Early Quadrille in London

We've written about the introduction of the Quadrille to London before, we will therefore only offer a brief summary here. It has often been suggested that the Quadrille was introduced to London by the military officers returning home from Waterloo who would have danced them in Brussels and Paris in 1815; there's certainly some truth to this theory but social history is rarely that linear. The term

The Quadrille dance was of course of French origin, at least in style, but that doesn't mean that every individual choreography and tune was known in Paris before it reached London. For example, one of the early Quadrilles that became popular in London was named Les Graces, it probably had a complicated trans-national origin. It was published several times in London in both 1816 and 1817. It is thought to have been of French origin as the music was published in Paris by Edmé Collinet in his c.1816 Premiere Recueil de Nouvelles Contre-Danses Francaises, et Walses; Collinet gave composition credit for the tune to Monsieur Rubner, another Frenchman. Rubner however was a leader of the orchestra at London's Vauxhall Gardens from around 1814 (he described himself as such on the cover of some of his 1819 publications, he also published contredances from the

The most important of the early Quadrille sets, at least in London, was named The First Set; the word

From a modern point of view identifying The Carlton House Fete might seem easy, it must have been a reference to the 1811 event at Carlton House that celebrated the start of the Regency, that's what most modern writers would mean by the phrase; but this might not have been so obvious back in 1816. For example, an 1818 publication named The Tablet of Memory; Showing Every Memorable Event in History from the Earliest Period to the Year 1817 offered brief descriptions of two historically significant events under the same name, one from 1811 and one from 1814: Let's consider what can be known about the dancing at the various Carlton House Balls across the period in which we're interested.

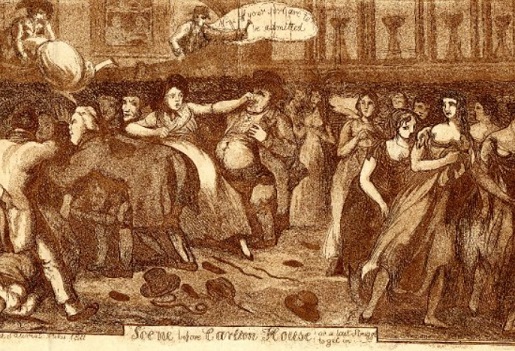

The Carlton House Fete, Wednesday 19th June 1811The Prince of Wales was appointed Prince Regent in February 1811 when his father (the King) was considered unfit to continue to rule. He held a grand ball in June 1811 in order to celebrate his ascension; officially the ball was held to celebrate his father's birthday but the guests were under no illusion, this ball marked the commencement of The Regency. The ball was well attended; some reports reference 2000 guests, some say 3000 others suggest 5000. Carlton House was a grand palace but it struggled to cope with such numbers (see Figure 2), even with giant marquees erected in the gardens behind the house. As the 1818 Tablet of Memory explained above, the numbers were so significant that many were hurt in the crush. This in turn implied that there was very little space for dancing in.  Figure 2. Scene before Carlton House, or a last struggle to get in, 1811. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 2. Scene before Carlton House, or a last struggle to get in, 1811. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

There are several surviving descriptions of the Fete; for example, The Morning Post newspaper shared an extended editorial about the Fete over three consecutive issues, the other newspapers offered only slightly less complete descriptions. La Belle Assemblée magazine published a similar report of the Fete that's available to read, courtesy of Google Books, their text was derived from that printed in The Examiner and The Herald (and probably elsewhere). We'll not repeat these extensive descriptions here as they have little to say about the dancing; a particularly good description of the Ball is also available from the Regency Redingote website that you might like to read. Two rooms had been set aside for dancing in; The Times newspaper for the 21st June 1811 recorded that: The ball-room floors were chalked in beautiful arabesque devices. In the centre of the largest were the initials G.III.R. It was divided for two sets of dancers by a crimson silk cord. One of the windows being taken out, had in the recess an orchestra, which diffused its melodies throughout the apartments. The anti-room adjoining was also set apart for dancing, the doors of which being kept open, one band in the drawing-room was sufficient for both. The floor of this room was very neatly ornamented; in the centre was the Prince Regent's crest (the feathers) in various colours, surrounded by musical notes, musical instruments, particularly those used in dancing, and various other devices; but owing to the great number of persons, and the excessive heat of the weather, no dancing took place in this room, nor were the dancers numerous in the ball-room. The Morning Post newspaper for the 22nd June 1811 explained further: About ten o'clock, dancing commenced in the Council Chamber; Mr Gow's excellent Band attended for the purpose. From the crowded state of the room, however, dancing was shortly discontinued, contrary to the wishes of the Prince, who used every exertion to set it on foot again; there was only one dance more during the remainder of the evening; the company appearing to prefer the promenading from one room to another, and gazing on the dazzling brilliancy which shone throughout this superb palace. A day earlier the Morning Post for the 21st June 1811 had listed the entire programme of dances, it also identified the dancers. The description below is from the Post, we've annotated additional details about the dancers in square brackets and identified the dance names in bold. The first couple who[1785-1847, 26, unmarried]tripped on the light fantastic toewere Earl Percy, and the accomplished, and deservedly celebrated beauty, Lady Jane Montague, the daughter of the Duchess of Manchester[1794-1815, 17, unmarried]; they led off with the dance calledMiss Johnstone, next followed:- The crowding and heat resulted in only two dances being performed all evening, contrary to the hopes of the Prince. We've studied these two dances in previous papers, you might like to follow the links to read more, they were Miss Johnstone and I'll gang nae mair to yon Town, both favourites of the Prince and well within the repertoire of the celebrated Gow band. There's no suggestion that Quadrilles were danced at this event and the over crowding ensured that they genuinely couldn't have been danced; several independent accounts of the ball combine to leave little doubt, it's highly unlikely that our Quadrilles were danced at the 1811 event, there simply wasn't the space to do so.

Grand Balls of 1813

There must have been many events held at Carlton House after the Fete of 1811, the press didn't comment upon such events in any detail however until the year 1813. There are references to the Regent holding court and levées at Carlton House in 1812 but no hints of a large society event. There were however several society Balls held in Carlton House in 1813, perhaps one of them featured our Quadrille. There's no obvious reason why a Quadrille publication of 1816 would refer to any of the 1813 events as  Figure 3. Carlton House as seen from the garden, 1812. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 3. Carlton House as seen from the garden, 1812. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

The first Grand Ball was held on Friday the 5th of February 1813, we've studied the dancing from that event in another paper. You might like to follow the link to read more. We're lucky to have a fairly complete list of the dances enjoyed, there's no hint of Quadrille dancing being involved. The Ball featured the same two Country Dances that we found being danced in 1811, together with a selection of similar country dancing tunes and a vague hint at a Polonaise March having being introduced. This ball, perhaps informally, introduced Princess Charlotte (1796-1817) into public life. A second event was held on Wednesday 30th June 1813, we've also studied the dancing from this event in a previous paper. It featured the same two tunes from 1811 embellished with a variety of popular tunes from 1813, once again there was no hint at a Quadrille being danced.

July of 1813 saw a variety of entertainments thrown in London in celebration of victory at the Battle of Vitoria, the foremost of which was a Gala held by the Prince outside Carlton House on Tuesday 6th July. This event may have involved Waltz dancing, the Kentish Weekly Post (13th July 1813) commented that The Queen and Princesses entered the grounds at three o'clock, by the Garden gate from St. James's Park; they were received by the Prince; the bands of the First, Coldstream, and 15th. Mr Rivolta, who plays seven instruments at one time, and several Pandeans, struck upGod Save the King. The Prince conducted the Queen to the lower part of the Lawn, attended by his officers of state. They were followed by the Princesses, the Princess Charlotte, the Duchess of York, Princess Sophia of Gloucester, the Dukes of York, Kent, and Cambridge, the Prince of Orange. They met the company who had arrived coming out of the back front of Carlton House into the grounds, who were received by the Prince, the Queen, and the whole of the Royal Family. They continued promenading for a considerable time, the different bands playing alternately, occasionally partaking of ices and other refreshments. The heat of the sun was so intense on the platform laid for dancing, that those who are fond of that fascinating exercise did not venture to commence till half past five o'clock, when a cooling breeze rendered it very refreshing, and between thirty and forty couple stood up. The first dance was led off by Princess Mary and Earl Percy, to the tune of Mrs McLeod of Eyre, which was played in a very superior style by an excellent band, stationed in the front of the Chinese Temple. Those who did not join in the merry dance, continued promenading through the groves, walks, and lawn. The Prince, and nearly the whole of the gentlemen in the full dress Windsor uniform, most of them walked without their hats. The ladies were very elegantly dressed for this princely entertainment. The bands, at distant parts from the dancing, continued playing alternately. The second dance was The Tank, led of by Princess Mary and Earl Percy. The third dance was led off by Princess Mary and the Duke of Devonshire, to the tune of Lord Dalhousie. Princess Charlotte danced with the Duke of Devonshire in the two first dances, and the last dance she led off with Lord Palmerston. No hint of Quadrille dancing can be found from this ball-like event either. We have studied most of the named dances elsewhere, you can follow the links to read more, they were: Mrs McLeod of Eyre, The Tank, Lord Dalhousie, Voulez vous danser Mademoiselle?, Sir David Hunter Blair and Henrico.

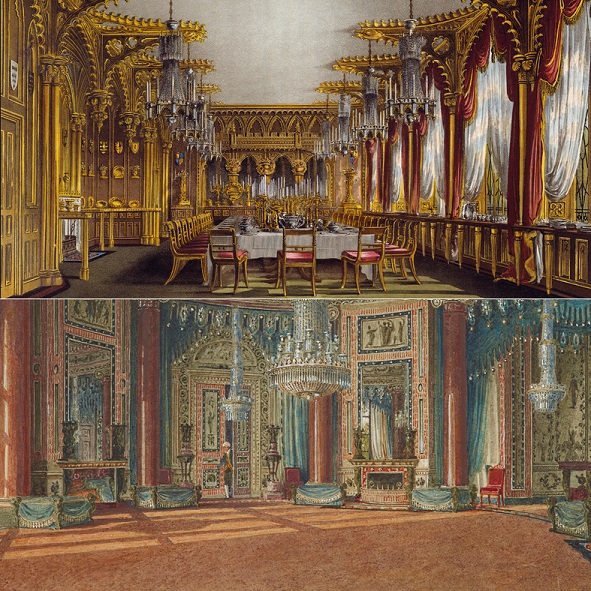

The Carlton House Fete, Thursday 21st July 18141814 was a year of celebration in Britain, it saw peace in Europe, the visit of the Allied Sovereigns and the centenary of the Hanoverian dynasty. A Royal Wedding was even under consideration as Princess Charlotte had been betrothed to the Hereditary Prince of Orange. The Prince Regent held a ball in July 1814, it was intended to celebrate Peace and the military triumphs of the Duke of Wellington (he had been made a Duke in May of 1814 in recognition of victory at the 1813 Battle of Vitoria). Once again the gardens of Carlton House were thrown open and a Ball was held in the evening; lavish Chinese pagodas were erected in the gardens in preparation. The Morning Post for the 23rd July 1814 recorded:  Figure 4. The interior of Carlton House, the Banqueting Hall (above) and the Circular Room (below), c.1819.

Figure 4. The interior of Carlton House, the Banqueting Hall (above) and the Circular Room (below), c.1819.

This was the only grand entertainment upon a large scale, that the Prince has given this season;...The whole of the entertainment was given in a style of elegance, splendour, and princely magnificence, far exceeding any that has ever been given in Carlton House, or in this country, well worthy of the great and gallant warrior, on account of whose unprecedented deeds of arms, which have resounded throughout the world, this princely banquet was prepared by his Sovereign in the person of the Prince Regent....The weather proving favourable, the Gardens at the back of the house were brilliantly illuminated with lamps, variegated lamps, &c. similar to Vauxhall Gardens; a small pyramid of variegated lamps was in constant motion; the Gardens were in consequence used by the elegants as a promenade; a small shower of rain fell about three o'clock, but not sufficient to prevent the Gardens being resorted to. A guard of honour was stationed in the Gardens. A guard of honour was also marched into the Court-yard about nine o'clock, with the band in their state dresses, to salute the Royal Family as they arrived, play martial pieces, &c. The front of the house and courtyard were illuminated with a number of additional lamps.... We don't have the complete list of dances for the event, several of the tunes what were named have been studied in our previous papers, they were: Miss Johnson, a Waltz Medley, General Kutusoff and Voulez vous danser, Mademoiselle?. There's no hint that Quadrilles were danced at the event, nor is there strong evidence that they weren't danced. We could at most conclude that it's possible our Quadrilles were danced at this Ball, though in all probability they weren't. One curiosity involving this ball is that a semi-permanent dancing space was erected in the garden of Carlton House for the dancers to use. That structure is known today as The Rotunda and it still survives at its later home of Woolwich Common. A detailed report on the building is available here courtesy of Historic England. The celebrated floor chalker George Glover was hired to decorate the floor of this Rotunda, there were evidently spaces for twelve Country Dancing sets radiating outwards from the centre of the structure. I am indebted to dance historian Cor Vanistendael for bringing this structure to my attention.

Returning to the newspaper reports of the ball, they were not as fawning as might normally have been predicted. Many of the newspapers barely mention the ball at all; the entire event was upstaged by a much more interesting story... that of the flight of Princess Charlotte, the second in line to the throne. Charlotte had been reluctantly betrothed to the Hereditary Prince of Orange in June 1814, she subsequently changed her mind and called off the engagement. The Regent, foiled in his plans, determined to isolate Charlotte by moving her into the Queen (her Grandmother)'s apartments; she attempted to flee to her mother, the associated stories in the press described what happened as an

One of the principle guests led off several of the dances with Princess Mary, this was the Saxon Prince of Sax Cobourg... we'll hear more of him in a moment. First let's hear how society hostess Mrs Frances Calvert (1767-1859) described her experiences of the event in her diary:

The Regent's Fete, Friday 12th July 1816The Regent seems not to have hosted a grand ball or fete in 1815 (at least not at Carlton House which was temporarily undergoing alterations) but he did once again in 1816. The celebrations of 1814 had proven to be premature: Napoleon not only returned from exile but warfare once again resumed culminating in the 1815 Battle of Waterloo. Princess Charlotte, by the date of the 1816 Ball, had been happily married to the Saxon Prince Leopold; this was the first grand ball hosted by the Regent since the wedding in early May 1816. Leopold was Charlotte's own choice of consort, they were understood to be very happy together. The Observer newspaper for the 14th July 1816 reported:  Figure 5. Two images from Tom Raw, the Griffin, 1828. Tom is seen preparing for a Quadrille (above) and causing a comotion in a ballroom (below).

Figure 5. Two images from Tom Raw, the Griffin, 1828. Tom is seen preparing for a Quadrille (above) and causing a comotion in a ballroom (below).

The Evening Mail newspaper for the 15th July 1816 continues the narrative:On Friday night, the Prince Regent gave a grand Ball and Supper at Carlton House, to a numerous party, which we believe to be the first his Royal Highness has given for these two years; and for the purpose of giving a spur to our national manufactures, a special notice was issued to those invited, that the Prince particularly desired that all would come dressed in British manufactured articles only, which was a very laudable act, and no doubt its influence will spread. A few further details can be found in the Morning Post newspaper for the 15th July 1816:After supper dancing was resumed, which was kept up till a late hour on Saturday morning. The dancing consisted only of waltzing and cotillons, in which none of the Royal Family joined. The Queen sat in her state chair, accompanied by the Prince Regent, who was close in his attendance upon his Royal Mother all the night. The company sat about an hour at supper, when dancing was resumed in the Rotunda, when a new country dance called Waterloo was led off by the Duke of Devonshire and a Lady whose name we did not learn.

A final detail emerges from the Kentish Gazette newspaper for the 16th July 1816 which reported:

We're informed that in 1816 the

1816 was a year for new beginnings; Napoleon had been banished for good in the aftermath of the 1815 Battle of Waterloo, Europe was reinventing itself and the Regent had every expectation of becoming a grandfather. A new (one might almost say The Prince was ever the leader of fashion. Once Quadrilles were danced at his fete they would increasingly be danced in ball-rooms around the country.

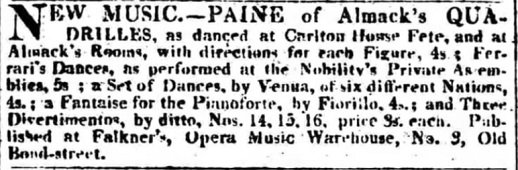

The Chronology of the First Set of Quadrilles Figure 6. Paine's advert for his Quadrilles, Morning Post, 19th July 1816. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Figure 6. Paine's advert for his Quadrilles, Morning Post, 19th July 1816. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

The evidence seems fairly compelling, James Paine's 1816 reference to Quadrilles having been danced at the Carlton House Fete was a reference to the event of 1816, not to the equivalent events of 1811 or 1814 (or indeed of any other year). This shouldn't really come as a surprise; a publication issued in 1816 wouldn't be named to impress an audience two hundred years in the future, it only aimed to impress potential customers in the weeks immediately following the Prince's Fete. The fact that

If we accept this argument then that offers the satisfying result that the story of the Quadrille doesn't change, it simply gains a little nuance. It's reasonable to assume that James Paine must have published his Quadrilles at some point after the 12th July 1816 (the date of the Fete); the earliest references I have to Paine's First Set actually existing is from an advert printed in the Morning Post newspaper for the 19th July 1816 (see Figure 6). It would appear that Paine hurried into print in roughly a week in order to promote his Quadrilles as being

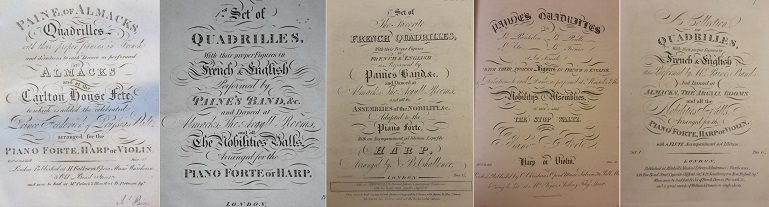

As we mentioned at the start of this paper, the term Paine was evidently correct to rush into print, several rival publishers issued variant editions of the Quadrilles shortly after his own publication. For example, Skillern & Challoner advertised their version in the Morning Post newspaper just four days later on the 23rd July 1816, you can follow the link to read more. Editions by Mitchell, Shade and Chappell also circulated in the months following (see Figure 10); there was clearly a market for the Quadrilles, posterity would consider Paine's arrangement and publication to be the most reliable, though dancers at the Fete may only have known Payne's version. The inevitable confusion between the rival editions of Edward Payne and James Paine would persist into the modern era.

The First Set as published by Payne had existed before the date of the Regent's 1816 Fete. We can infer that it was this event that transformed the First Set from being an ordinary Quadrille set into becoming

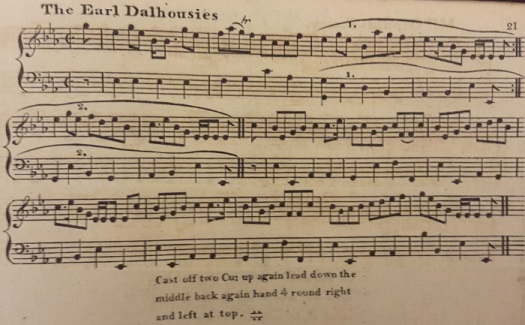

Figure 7. The Earl Dalhousies from Broderip & Wilkinson's c.1806 Selection of the most Admired Dances, Reels, Waltz's, Strathspeys & Cotillons

Figure 7. The Earl Dalhousies from Broderip & Wilkinson's c.1806 Selection of the most Admired Dances, Reels, Waltz's, Strathspeys & Cotillons

Earl of Dalhousies ReelThe third dance was led off by Princess Mary and the Duke of Devonshire, to the tune of Lord Dalhousie.(July 1813)

This tune was composed by Nathaniel Gow and was first published in Edinburgh c.1800 under the name Earl of Dalhousies Reel; it was the companion to another tune named Lady Mary Ramsay's Strathspey, the two tunes being arranged together as a Medley. Gow published them in combination in his 1800 Lady Mary Ramsay's Strathspey publication. The tune was then incorporated within Neil Gow's 1800 A Fourth Collection of Strathspey Reels and entered the regular repertoire of the Gow bands. It was reported of the Queen's Assembly in Edinburgh (Caledonian Mercury, 23rd January 1800) that The tune then appeared in a few London publications; it can be found within the Preston collection of 24 Country Dances for 1802 under the name Lady Dalhousies Reel and in Broderip & Wilkinson's c.1806 Selection of the most Admired Dances, Reels, Waltz's, Strathspeys & Cotillons (see Figure 7). References to the tune then seem to disappear only for it to re-emerge at our ball of 1813. Following the excitement of it once again being danced in Royal circles the tune was published in Cahusac's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1814, this time under the new name of Lord Dalhousie. Several other tunes appeared under similar titles in London at about the same 1814 date, there's unlikely to have been any confusion however, the Gow tune was almost certainly what was featured at our Ball. The similarly named tunes may only have been created in response to the success and relative obscurity of the first tune.

The Earl himself is easily identified, he was George Ramsay (1770-1838), the 9th Earl of Dalhousie; Lady Mary Ramsay was his younger sister (1780-1866). Dalhousie was a career soldier who had fought in many campaigns. The Gows dedicated many dozens of tunes to the various members of the Scottish peerage, including several to the Dalhousie family; in addition to the two tunes already mentioned a report from 1806 (Morning Post, 29th November 1806) mentioned a tune named Lord Ramsay that We've animated a suggested arrangement of the Broderip & Wilkinson c.1806 version. For futher references to the tune, see also: Earl of Dalhousie's Reel (2) at The Traditional Tune Archive

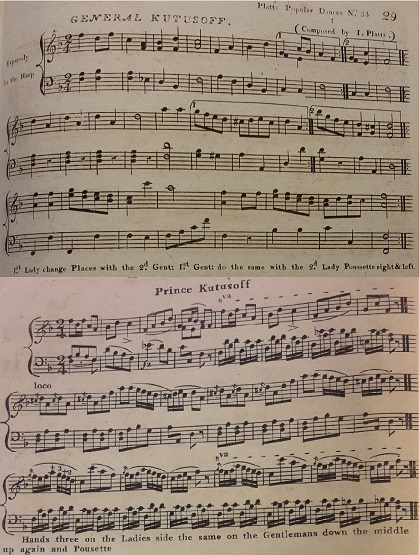

Figure 8. General Kutusoff from James Platts's 1813 34th Number (top) and Prince Kutusoff from Skillern & Challoner's c.1813 19th Number (bottom). Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(10.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, bottom image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.925.o ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 8. General Kutusoff from James Platts's 1813 34th Number (top) and Prince Kutusoff from Skillern & Challoner's c.1813 19th Number (bottom). Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(10.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, bottom image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.925.o ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

General KutusoffThe same parties led off the two following dances, to a Waltz Medley and General Kutusoff.(July 1814) Prince Mikhail Kutuzov (1745-1813) was the senior Russian General who oversaw the defence of Moscow in 1812, together with the subsequent expulsion of the Napoleonic armies thereafter. His name regularly appeared in the British newspapers in both 1812 and 1813, latterly alongside stories of catastrophic French defeats. He died in 1813 before the date of our Ball but his name retained significance in London; he was one of the allied generals who had helped to secure victory in Europe, paving the way for Tsar Alexander's capture of Paris in early 1814. The Tsar himself had visited London in June 1814 and the nation was still celebrating; positive sentiment towards all things Russian remained in the air.

At least four country dancing tunes were printed in London between about 1813 and 1816 named either Our candidate tunes are:

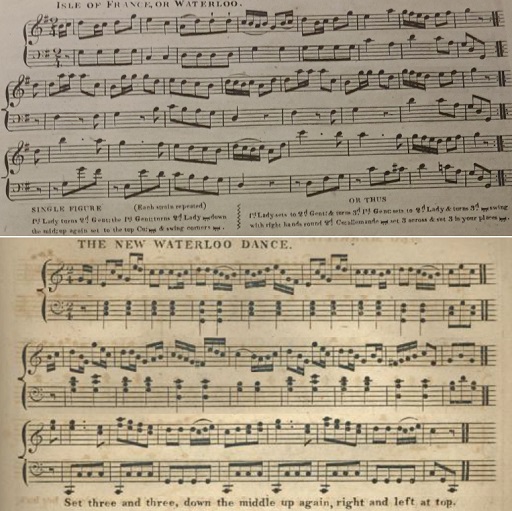

The Waterloo Dance... a new country dance called Waterloo was led off by the Duke of Devonshire and a Lady whose name we did not learn.(July 1816) The peace celebrations of 1814 proved to be premature, Napoleon returned from exile in March 1815 initiating the period known to history as the Hundred Days. Entire regiments flocked to Napoleon's banner and war began anew. The principle engagement of the period was the Battle of Waterloo, it would prove to be the final and decisive battle of the Napoleonic Wars; the victory was absolute and Napoleon was irrevocably defeated. It was perhaps inevitable that a multitude of tunes would be named in the aftermath, the diversity of possibilities means that we can't identify our 1816 tune with any degree of certainty. All that we do know is that the tune must have existed in 1816 (tunes that are only know from 1817 or later are unlikely to have been used), and that the dance was led off by William Cavendish (1790-1858) the 6th Duke of Devonshire.  Figure 9. Isle of France, or Waterloo from Button & Whitaker's c.1816 30th Number (top) and The New Waterloo Dance from Clementi's c.1817 26th Number (below). Upper image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.aa ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 9. Isle of France, or Waterloo from Button & Whitaker's c.1816 30th Number (top) and The New Waterloo Dance from Clementi's c.1817 26th Number (below). Upper image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.aa ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

At least a dozen different tunes named for some variation of

For futher references to one of the tunes, see also: Waterloo Dance (1) at The Traditional Tune Archive

Paine's First Set of QuadrillesThe dancing consisted only of waltzing and cotillons, in which none of the Royal Family joined.(July 1816) Dancing was resumed about three, and concluded at five o'clock with a new French country dance, the figure of which is very graceful and the music charming.(July 1816)  Figure 10. A medley of c.1816 First Set publications; Paine's publication (far left), Chappell's publication (middle left), Skillern & Challoner's publication (middle), Payne's perhaps 1815 publication (middle right) and Mitchell's publication (far right).

Figure 10. A medley of c.1816 First Set publications; Paine's publication (far left), Chappell's publication (middle left), Skillern & Challoner's publication (middle), Payne's perhaps 1815 publication (middle right) and Mitchell's publication (far right).

For the sake of completeness it seems appropriate to take a quick look at Paine's First Set of Quadrilles. The reports of the 1816 ball only referenced Cotillons or French Country Dances as having been danced, but this paper has demonstrated that in all probability the First Set of Quadrilles were indeed part of the repertoire for the Regent's Fete. They were probably danced to the music arranged and published by James Paine using the figures as taught and published by Edward Payne. Each of the tunes in Paine's first set has a name, so too do the sequences of Dancing figures. The figures are known as La Pantalon, L'Ete, La Poule, La Trenise, La Pastorale and Promenade; these same named sequences also appeared in Edward Payne's first set of Quadrilles (with some minor variations), they have a rich provenance in their own right. Paine's tunes also have names, they are La Paysanne, La Flora, Le Cobourg, La Felesia, La Pastorale and La Nouvelle Chasse. If you'd like to know more about dancing the figures then you might like to review our separate paper on that subject. It's not clear whether Paine's music was arranged especially for the 1816 Ball or whether it was already established, it seems likely that Paine's band had been playing these arrangements at Almack's Assembly Rooms in the months prior to the Fete. The Quadrille figures would almost certainly have been known to the dancers already as it's difficult to believe that they would have been taught in-situ mid-ball; the figures may nonetheless have been announced by a director of dancing, it was reported (by G.M.S. Chivers in his 1824 Quadrille Preceptor) that the convention at Almacks Assembly Rooms involved calling (i.e. announcing) the figures in French.

We're informed that at least one French Country Dance was led off by the Figure 10 shows five First Set publications published in London c.1816, four of them specifically refer to the Quadrilles as being played by Paine's band and feature different arrangements of the same musical score. Edward Payne's publication pre-dates the others, it uses different music and could have been published as early as 1815; the James Paine and Skillern & Challoner publications were issued shortly after the Regent's 1816 Fete, the Chappell and Mitchell publications are a little later still, perhaps as late as 1817. Several other publishers issued similar copies of the First Set at around the same date, for example George Shade issued his Collection of Quadrilles no 1 c.1816, it was another variation on the same theme. It seems that Paine rushed to publish his version of the First Set in the immediate aftermath of the 1816 Fete; he advertised it as being ready for sale a mere week later; this urgency may have contributed to the imperfections of his text... the minutiae of his figures have generated confusion over the arrangement of the dances ever since! I find Edward Payne's slightly earlier descriptions of the figures to be rather easier to comprehend (though he did update and evolve his text over several editions of his publications), you might like to follow the link to read more.

ConclusionWe have studied a series of balls held at Carlton House during the Prince's reign as Prince Regent; other balls were of course held prior to 1811, more would be held after 1816 (though Carlton House was demolished in 1826), smaller events must have been enjoyed on a regular basis throughout this period. Our investigation has only considered the most significant of the Royal Fetes, those for which details were published by the press. We have seen once again that the predominant style of dancing varied over time; at the earlier date most of the dancing involved Country Dances, at the later date it was Waltzes and Quadrilles. A selection of the most fashionable tunes were featured at the balls, together with new tunes with politically meaningful names. We've also seen how the personal lives of the Royal Family could intersect with these grand state events; Princess Charlotte in particular seems to have had an important life event coincide with many of the balls and fetes. We have resolved with reasonable certainty the mystery of the date at which Quadrilles were first danced at a Carlton House Fete, and discovered in the process that the iconic 1816 Paine of Almacks Quadrilles by James Paine might have been rushed into print in as little as a week! That final revelation came as a surprise to me.We'll leave this investigation there; if you have further information to share do please Contact Us as we'd love to know more.

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved