| Return to Index |

|

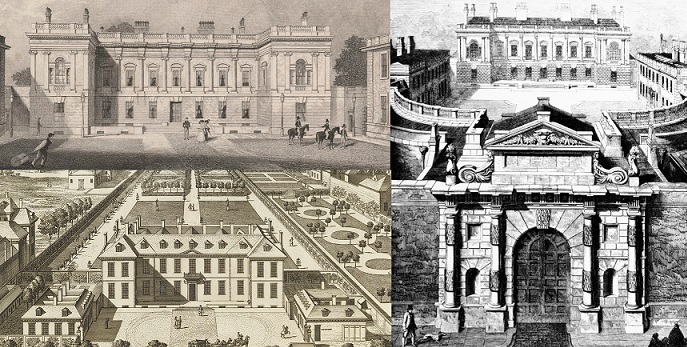

Paper 48 Burlington House (and other) Balls of 1814Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 24th January 2021, Last Changed - 12th February 2024] Figure 1. Three views of Burlington House. 1831 (above, courtesy of the Royal Academy of Arts); c.1698 (below, courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust); and 1854 (right, courtesy of British History Online).

Figure 1. Three views of Burlington House. 1831 (above, courtesy of the Royal Academy of Arts); c.1698 (below, courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust); and 1854 (right, courtesy of British History Online).

Burlington House in central London (see Figure 1) hosted several significant social events in the summer of 1814, most notably the White's Club ball at which the Tsar of Russia famously waltzed with the British aristocracy. In this paper we'll consider several social events hosted at Burlington House that same year, together with other events of 1814 that may offer insight into the nature of the dancing at the Burlington events. In addition to studying the various Burlington House Balls of 1814 we will also study the following tunes and dances in this paper:

Burlington House and the Dukes of DevonshireBurlington House, Piccadilly (see Figure 1 and Figure 2), is one of London's great mansion houses. It was built by the Earls of Burlington, the third of whom was Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington (1694-1753); Richard died with no male heir and so the property was inherited by his son-in-law William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire (1720-1764). Cavendish received the title Duke of Devonshire when his own father died in 1755, this resulted in Cavendish owning two massive mansion houses in close proximity in Piccadilly, Burlington House and Devonshire House. Devonshire House would remain the Duke's London home, Burlington House was instead made available to other members of his family.  Figure 2. William Spencer Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire (1790-1858), the owner of Burlington House c.1816 (left), and the location of Burlington House in Piccadilly from the Horwood Map of 1792-9.

Figure 2. William Spencer Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire (1790-1858), the owner of Burlington House c.1816 (left), and the location of Burlington House in Piccadilly from the Horwood Map of 1792-9.

Cavendish had several children. The oldest was William Cavendish (1748-1811), later the 5th Duke of Devonshire. It was William who would inherit both properties in 1764. Next was Lady Dorothy Cavendish (1750-1794), she married William Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland (1738-1809) in 1766, they would occupy Burlington House together for many years (Portland was the Prime Minister between 1807 and 1809). The younger of the 4th Duke's sons was George Cavendish (1754-1834), later the 1st Earl of Burlington (2nd Creation). George Cavendish would purchase Burlington House from his nephew William Cavendish (1790-1858) (the 6th Duke of Devonshire, son of the 5th Duke, see Figure 2) in 1815. The property was largely unoccupied at our key date of 1814, though it had been considered as a temporary home for the Prince Regent while Carlton House was undergoing refurbishment (Morning Chronicle, 5th February 1814). The various occupants of Burlington House must have hosted many social events there, a few were sufficiently notable to be discussed in the press.

The Hull Packet newspaper for the 16th July 1811 described one such event. The Duke of Portland had died back in 1809 and Burlington House was owned by the 5th Duke of Devonshire; the Duke's son (the Marquis of Hartington, who shortly thereafter would become the 6th Duke of Devonshire, see Figure 2), was hosting a grand fete probably in celebration of his 21st Birthday; the Hull Packet reported:

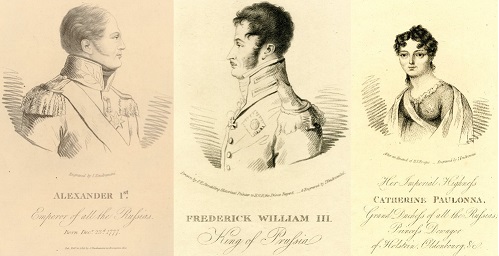

The Celebrations of 1814 Figure 3. Images from the 1815 A Series of Sixteen Portraits of the most Illustrious Persons who visited London in the month of June 1814, courtesy of the British Museum. The images are: Alexander 1st of Russia (left), Frederick William III of Prussia (centre), and Catherine Paulonna Duchess of Oldenburg (right).

Figure 3. Images from the 1815 A Series of Sixteen Portraits of the most Illustrious Persons who visited London in the month of June 1814, courtesy of the British Museum. The images are: Alexander 1st of Russia (left), Frederick William III of Prussia (centre), and Catherine Paulonna Duchess of Oldenburg (right).

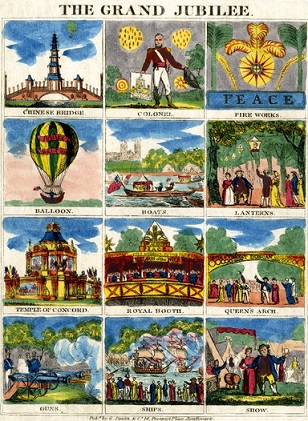

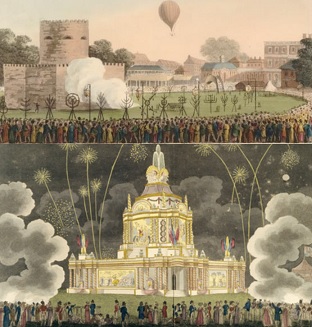

1814 was a celebratory year in Britain. The year opened with the expectation that the wars in Europe were finally ending, the allies being victorious over the Napoleonic French. The Prince of Orange had returned to the Netherlands to set up a new and independent government at the end of 1813 and the allies under Tsar Alexander won the Battle of Paris in late March 1814. This was followed by the Marquess of Wellington claiming victory at the Battle of Toulouse in April. The fighting, at least in Europe, was over and Napoleon was forced to abdicate. Wellington was appointed the Duke of Wellington in early May of 1814 amidst general celebrations of Britain gained new territories, at least initially, as part of the peace settlements. The May 1814 Treaty of Paris saw Britain officially take the islands of Tobago, St Lucia, the Seychelles and Mauritius; King George III had been restored to the Hanoverian territories in 1813, October 1814 saw him officially named the King of Hanover in addition to being King of the United Kingdom. August of 1814 also marked the celebration of the Brunswick Centenary, the 100th anniversary of the accession of the Hanoverian dynasty in Britain; this was marked by nationwide celebrations of a Grand National Jubilee. The celebrations of August encompassed both the General Peace and the Brunswick Centenary; a Naumachia (recreation of naval battles, see Figure 9) was fought on the Serpentine and both a Chinese Pagoda and a revolving Temple of Concord were opened - August marked the peak of the celebratory mood, great crowds of Londoners attended the public events (many of which can be seen in Figure 8).

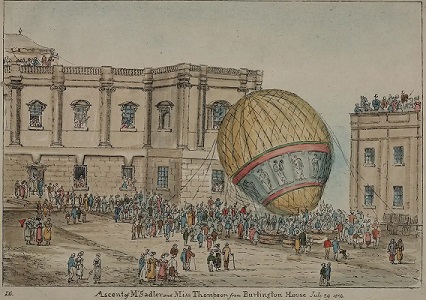

A delegation of allied sovereigns visited London in June 1814, they included both Tsar Alexander I (1777-1825) of Russia, his sister the Duchess of Oldenburg (1788-1819), and King Frederick III (1770-1840) of Prussia (see Figure 3). Numerous state events were held in their honour, their visit marked the start of the summer of celebrations. Burlington House was to feature heavily in these society events; the activities there would include a grand ball, a masquerade, and the gardens would be used to launch what was thought to be the largest hot-air balloon ever made (Hampshire Chronicle, 27th June 1814). It would later be reported of the balloon in the Windsor and Eton Express for the 10th July 1814 that A further consideration in 1814 involved the now 18 year old Princess Charlotte (1796-1817). She was expected (hopefully many years later in life) to become the Queen of England, she would require a suitable prince consort. Speculation was rife over who would be selected. She was officially betrothed to the Hereditary Prince of Orange (1792-1849) in June of 1814; the engagement didn't last long but her future and that of Britain itself were thought to be inextricably linked. The man she eventually married in 1816 was Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (1790-1865), he was a Lieutenant-General in the Russian cavalry and is understood to have been part of the Tsar's delegation of 1814. Their meeting must have been of some significance.

The White's Club Ball, Burlington House, 20th June 1814The influential gentleman's club White's hosted a fete at Burlington House during the visit of the foreign sovereigns. White's had a reputation as a gambling and gaming venue, it was also a bastion of Tory politics (the Whigs tended to congregate at the nearby Brook's club). This fete would be one of the principal events of the visit, at least from the point of view of the 2400 or more guests who were present; the cost to White's of hosting it was recorded to have been just short of £10,000. The principal guests spent the day of the 20th at a military review held in Hyde Park (see Figure 5).  Figure 4. Ascent of Mr Sadler and Miss Thompson from Burlington House, July 29 1814, image courtesy of the London Metropolitan Archives.

Figure 4. Ascent of Mr Sadler and Miss Thompson from Burlington House, July 29 1814, image courtesy of the London Metropolitan Archives.

Preparations were being made well in advance of the evening's ball. Several newspapers carried instructions for attendees; for example the Courier for the 15th of June 1814 reported that: Organising this event would involve significant effort. Most of the newspapers carried coverage of the event, several offered detailed accounts (most of which reused essentially the same text). What follows is an edited description of the event as recorded in Bell's Weekly Messenger for the 26th June 1814 (dance references have been highlighted in bold): This festival, which took place on Monday from its length of preparation, from its costliness, and from the distinguished rank of the personages for whom it was chiefly destined, might have been expected to exhibit a magnificent display of what could be done by British hospitality; nor was this expectation disappointed. The company began to assemble at nine....  Figure 5. Review in Hyde Park attended by Allied Sovereigns, 20 June 1814 (this military review was held on the same day as the White's Club Ball); image courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust. The horsemen in the foreground are understood to be: Field Marshall Blucher, the Duke of Wellington, the King of Prussia, the Prince Regent, the Emperor Alexander and the Hetman Platoff.

Figure 5. Review in Hyde Park attended by Allied Sovereigns, 20 June 1814 (this military review was held on the same day as the White's Club Ball); image courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust. The horsemen in the foreground are understood to be: Field Marshall Blucher, the Duke of Wellington, the King of Prussia, the Prince Regent, the Emperor Alexander and the Hetman Platoff.

The Emperor Alexander waltzed with at least ten young ladies, selecting his partners for their shape and beauty, regardless of their rank or distinction. The company began to dance at half past twelve o'clock, led off with waltzes by the Emperor and the beautiful Countess of Jersey. The young Prussian Princes were likewise among the first who danced. There were waltzing parties at the upper end of the ball-room, and country dances below. In the centre sat the Prince Regent, in a chair of state, to which he was conducted, with all the usual etiquette, by the Dukes of Richmond, Beaufort, and Grafton. On the right and left were six other state chairs, covered with crimson velvet, and ornamented with burnished gold; the one on the right was empty, that on the left was occupied by the King of Prussia. The Emperor is not an epicure; he did not do much honour to the banquet; in less than ten minutes he arose and returned to the ball room, wherein his Majesty singled out a very young lady, and went down two country dances. Of the taste and judgement displayed in the dancing, it is impossible to speak in adequate terms of praise. The Emperor is an excellent dancer; French cotillions and figures, English and Scotch country-dances, waltzes, minuets or reels; none came amiss to him. Almost the whole of the fashionable world were there, mustering 2500 persons. Lord Viscount Sydney and Mr Freemantle presided at the management of the supper (which was most admirably set out), and they likewise had the whole of the interior arrangements under their control. Behind the Emperor of Russia's chair stood the Duke of Grafton; the Prince Regent's, the Duke of Richmond; and the King of Prussia's, the Duke of Devonshire. The Grand Duchess of Oldenburgh was a massy illumination of transcendent brilliancy, appearing one blaze of diamonds!

The dancing at this event consisted of the couple Waltz and Country Dances. The reference to

The society hostess Mrs Frances Calvert (1767-1859) wrote her personal recollections of attending this ball in her diary:

As a brief aside, this event is also of some interest to Jane Austen enthusiasts as her brother Henry is understood to have been one of the many guests who were present. Jane wrote to her sister Cassandra on the 23rd of June 1814

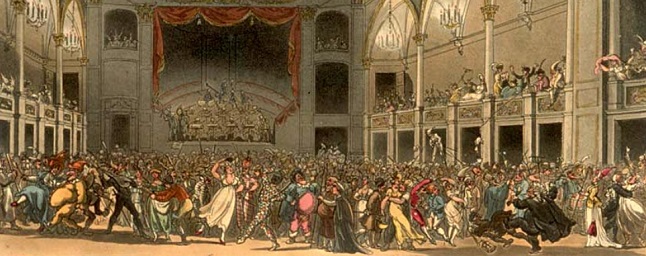

The Watier's Club Masquerade, Burlington House, 1st July 1814A second gentleman's club held a Masquerade Ball at Burlington House at the start of July 1814, this time under the auspice's of Watier's Club. The Masquerade was a Ball-like event in which the attendees disguised their appearance through use of costumes and masks; the event was held in honour of the Duke of Wellington (the visiting sovereigns having returned to Europe by this date). The Morning Post newspaper for the 8th July 1814 recorded of the masquerade (dance references are highlighted in bold):  Figure 6. An 1809 Masquerade Ball at the Pantheon, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 6. An 1809 Masquerade Ball at the Pantheon, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Although it is impossible to give any adequate description of the Masqued Ball which took place at Burlington House, on Friday night, in honour of the Duke of Wellington, and in commemoration of the glorious victories which this hero has gained, the following sketch may not prove unacceptable. Since the brilliant fete given at Carlton House two years ago by the Prince, no entertainment has been conducted with so much splendour and magnificence, as that which forms the subject of these remarks; for although the Ball given by the Members of White's Club last Monday week, was peculiarly interesting, from the presence of the Allied Sovereigns, in point of grandeur and sublimity, perhaps might be even added,...interest(which we consider the object for which it was given, namely, the celebration of the arrival of the greatest warrior which this or any other country has produced), this Fete certainly eclipsed it! As early as half past nine o'clock the company began to assemble at the scene of action, and from the same excellent regulations which were made by the Conductors of White's Fete, with regard to the carriages, no confusion whatever took place in the line of carriages, which, observing strictly the printed rules pointed out to them, drove up to the grand entrance of Burlington House with the most surprising facility.  Figure 7. Russian Condescension or The Blessings of Universal Peace, 1814. Tsar Alexander and his sister the Duchess of Oldenburg are accosted by British peasants while out walking. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 7. Russian Condescension or The Blessings of Universal Peace, 1814. Tsar Alexander and his sister the Duchess of Oldenburg are accosted by British peasants while out walking. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

When we consider the occasion which gave rise to the superb entertainment, and the circumstances connected with it, it must be considered as equal if not superior to any thing of the kind ever before given in this country. Who will not rejoice at some future period at having been present at thisfete, given expressly to celebrate the return of an Officer, who, by his brilliant succession of victories unparalleled in history, has immortalised his name as long as the world shall exist, and brought his country to a pitch of military glory and renown hitherto unexampled. The company left Burlington House at seven o'clock, and even at that late hour with regret. The Blues and Foot Guards were stationed without and within Burlington-House coach-yard, and conducted themselves with their usual propriety and forbearance.

Once again we read that Waltzes and Country Dances were the entertainments of the evening, on this occasion the Waltzing was apparently preferred. The Bury and Norwich Post for the 6th July 1814 offered further insight into some of the costumes worn:

The Grand Military Fete, Burlington House, 18th July 1814A further major event was held at Burlington House just a couple of weeks later, this event resulted in such verbose coverage from the Post that they had to split it across two editions. It was hosted by the General Officers of the Army and dedicated once again to the Duke of Wellington. The Morning Post for the 19th July 1814 reported (with dance references emphasised in bold):  Figure 8. The Grand Jubilee. A selection of images depicting the entertainments of August 1814. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 8. The Grand Jubilee. A selection of images depicting the entertainments of August 1814. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

This grand entertainment and splendid spectacle took place last night in the gardens of Burlington. Since the celebrated Fete given by White's Club, alterations and improvements have been made at every subsequent one. It was supposed, that the arrangements at Watier's could not be excelled; but, from the changes produced here, they were found to be far short of the...ne plus ultraof perfection. An Admirable revolution has been produced in the whole of thetout ensemble. They continued the following day: About eleven o'clock, the line of carriages extended from Davies-street, Berkeley-square, to Picadilly. The company began to enter Burlington-house soon after. To describe the sensation produced is impossible - it was...electric!all stood in mute astonishment, confounded with the glare and glitter around them.We mean by the introduction of the prominent feature, i.e....The Bust of Wellington.This theme of panegyric was placed in the Temple, dedicated to Peace. Once again we read that waltzing was the primary entertainment of the evening. One Country Dancing tune was named on this occasion, it was the White Cockade, a tune that was associated (by name alone) with the Bourbon ascendancy in France; we've studied this tune before, you might like to follow the link to read more.

Figure 9. The Naumacia to Commemorate a Peace, 23rd July 1814. The Naumachia was held on the 1st of August 1814, this image predates the event. Image courtesy of The MET.

Figure 9. The Naumacia to Commemorate a Peace, 23rd July 1814. The Naumachia was held on the 1st of August 1814, this image predates the event. Image courtesy of The MET.

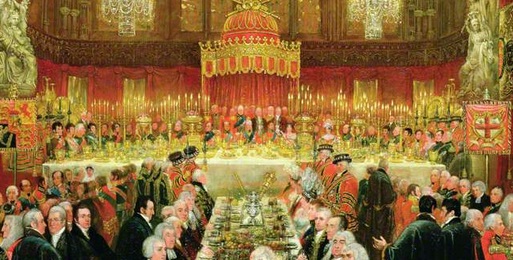

Other events held at Burlington HouseThe unoccupied Burlington House was found to be an ideal venue for large events throughout the summer of 1814, especially after the preparatory work had already been carried out by White's. Other major events included a Dinner held by White's Club celebrating Wellington's victories on the 7th July and a similar meal on the 11th hosted by the East India Company. An earlier formal Banquet held at the Guildhall is depicted in Figure 10. It was reported in August of 1814 that the Duke of Devonshire wished to sell Burlington House (eg Morning Post, 11th August 1814); rumours circulated and the property was eventually sold in early 1815 to the Duke's uncle Lord George Cavendish (he would go on to receive the title of 1st Earl of Burlington in 1831). With this sale the house was once again occupied, Lord George would begin hosting private events shortly thereafter. For example, a ball to mark his daughter's coming of age was reported in the Morning Chronicle for the 4th May 1815, they wrote (with dance references highlighted in bold): On Monday night Lord and Lady G.H. Cavendish opened Burlington House to their fashionable friends with a most magnificent ball and supper. The grand colonnade round the Court-yard was illuminated; on each side of the entrance were two crowns of variegated lamps. The superb suite of five drawing rooms were brilliantly illuminated, as was also the ball-room, which was hung with festoons of artificial flowers. The suite of rooms and library, were appropriated for the supper tables, where four hundred and fifty covers were laid. At half-past eleven dancing commenced with the following couples to the tune of Calder Fair:-  Figure 10. The Allied Sovereigns' Banquet at the Guildhall on the 18th June 1814, image courtesy of the City of London Corporation.

Figure 10. The Allied Sovereigns' Banquet at the Guildhall on the 18th June 1814, image courtesy of the City of London Corporation.

After 1814 Burlington ceased to be the centre of the fashionable world's attention, it would instead revert to being a private (albeit palatial) dwelling place. It's at this point that we'll leave our investigations into the events at Burlington House itself. We have now encountered the names of two popular Country Dancing tunes that were genuinely danced at Burlington, one danced at the house in 1814 (White Cockade) and another in 1815 (Calder Fair). We've studied both of these tunes in previous papers, you might like to follow the links to read more). Many other tunes were popular at around this same date and could perhaps have been danced there, we've encountered a few examples in our previous papers. We have previously studied a ball held at Carlton House on the 21st of July 1814 that included the tunes Miss Johnson, General Kutusoff and Voulez vous danser, Mademoiselle?; we also studied an event of January 1814 that included the tunes Orange Boven and the Sicilian Dance. If you wanted to recreate a Burlington event then any of these tunes would be suitable for use, it's quite likely that one or more of them would have featured at the Burlington events. We will now review three further descriptions of balls held around the country in 1814. In so doing we'll encounter the names of a few more popular tunes that could potentially have been danced at Burlington during that busy summer. These three events have been selected as they are rare examples for which the names of the tunes were printed in the press (most such reports do not offer this useful detail); it's purely by chance that they also represent a diverse range of events: a formal ball held in Dublin, a celebratory ball held in a small provincial town and a military ball held at a fashionable resort.

Celebration of the Queen's Birth Day, Dublin Castle, 24th February 1814The first of the extra events we'll consider was hosted in Ireland. The Morning Post newspaper for the 4th March 1814 reported (with dance references emphasised in bold):  Figure 11. The Allied Sovereigns at Petworth, 24 June, 1814. Image courtesy of the National Trust.

Figure 11. The Allied Sovereigns at Petworth, 24 June, 1814. Image courtesy of the National Trust.

Her Majesty's Birth Night was celebrated in a style of magnificence and grandeur at Dublin Castle, on Thursday (Feb 24), that has seldom been witnessed in this country. The company began to assemble soon after nine o'clock, and upon the entrance of his Excellency the Lord Lieutenant and her Grace the Duchess of Dorset, and their suite, shortly after ten o'clock, St Patrick's Hall presented a grand assemblage of all the rank and fashion of this country. The room was so crowded, that the Chamberlain found it necessary to order the velvet benches to be brought into the ball-room from the Presence Chamber, for the accommodation of the company, notwithstanding upwards of thirty Ladies were obliged to remain without seats. Upon the entrance of the Lord Lieutenant and her Grace, the company rose, and the band at the same time playedGod save the King,which had the most sublime effect. This event was conducted in the style of a formal court ball, it began with the increasingly anachronistic Minuet couple dances and concluded with country dances. It would appear that there were so few men capable of dancing the Minuet that a single gent was required to dance all four of them! The minuet had been falling from favour since the end of the 18th century, even formal events were increasingly likely to forego them, this event is unusual in retaining the Minuet to such a relatively late date. We've written more of the minuet elsewhere, you might like to follow the link to read more. One of the dances from this event was named Lady Montgomery, we've studied it in a previous paper, you might like to follow the link to read more.

Ball at Stratton, 30th June 1814The Royal Cornwall Gazette for the 9th July 1814 reported on a ball held in the small Cornish town of Stratton (dance references are emphasised in bold):  Figure 12. The Tower & Preparation of the Fire Works, with the Balloon (above, courtesy of the British Museum); A Perspective of the Revolving Temple of Concord (below, courtesy of the Museum of London). The tower facade was removed to reveal the revolving temple.

Figure 12. The Tower & Preparation of the Fire Works, with the Balloon (above, courtesy of the British Museum); A Perspective of the Revolving Temple of Concord (below, courtesy of the Museum of London). The tower facade was removed to reveal the revolving temple.

The ball at Stratton, on Thursday the 30th of June, in celebration of the late glorious events, and their termination in a Peace, was very respectably attended. The principal inhabitants of the neighbourhood, with their friends and visitors, assembled at the ball-room about eight o'clock, soon after which dancing commenced and continued until about midnight, when the numerous company partook of an elegantpetite soupe, consisting principally of meats and desert dishes, preserved and dried fruits, and all the fresh fruits of the season, together with a copious supply of choice wines. It's quite interesting to read of a ball that was hosted on a less majestic scale than those of the big Burlington events. It's perhaps of note that there were no hints of waltzing being enjoyed at this provincial event, unlike the London balls of a similar date. The dancing tunes that were employed at Stratton were generally popular, we've studied several of them before: White Cockade, The Tank, and Voulez vous dancer Ma'mselle?. You might like to follow the links to read more of these tunes.

Ball at Weymouth, 6th October 1814 Figure 13. The Jubilee Fair 1814, the subtitle reads This fair and naumachy or sham sea fight in Hyde Park was in honour of peace. This jubilee on Augt. 1, 1814, was to celebrate the return of peace and the centenary of the reign of the illustrious House of Brunswick and to commemorate the glorious Battle of the Nile. Image courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library.

Figure 13. The Jubilee Fair 1814, the subtitle reads This fair and naumachy or sham sea fight in Hyde Park was in honour of peace. This jubilee on Augt. 1, 1814, was to celebrate the return of peace and the centenary of the reign of the illustrious House of Brunswick and to commemorate the glorious Battle of the Nile. Image courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library.

The Morning Post newspaper for the 12th October 1814 reported of a Ball at Weymouth (with dance references highlighted in bold): On Thursday, Colonel Doherty and the Officers of the 13th Light Dragoons, also gave a most superb Military Ball and Supper, at the Royal Hotel Assembly Rooms, to every person of rank and fashion in this town and neighbourhood, and in that style of elegance for which the Gentlemen of the Army on these occasions appear so conspicuous. The dancing commenced precisely at ten o'clock, by Colonel Doherty, leading off with the accomplished Mrs Schuyler, to the air of Mrs McCloud; next the tune ofVoulez vous Danser,Enrico,The Cameronian Rant&c. were kept up with the utmost cheerfulness till half-past one, when Russel announced that the supper tables were arranged; and although we have had frequent opportunities of noticing his creditable exertions on these public occasions, still we cannot omit saying, that in the luxurious display of every wine and delicacy that could gratify the taste, and the season affords, no assemblage appeared to be more fully satisfied. Weymouth was a popular resort, fashionables from across the country would travel there for the season. We read that waltzing was enjoyed at Weymouth, so too were country dances; we've studied two of the named tunes in previous papers: Voulez vous Danser and Enrico, you might like to follow the links to read more.

The Couple Waltz Figure 14. Waltzing, 1825. Image courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library.

Figure 14. Waltzing, 1825. Image courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library.

The Emperor Alexander waltzed with at least ten young ladies...There were waltzing parties at the upper end of the ball-room, and country dances below(White's Club Ball, 1814) In the middle of the room were Waltzes, and in another part Country Dances....Among the Waltzers we noticed the Duke of Devonshire, Argyle, and Leinster; Waltzes seemed to be the order of the evening, for till the sun beamed, no Country Dances were performed.(Watier's Club Masquerade, 1814) The chalking of the floor was truly admirable....At the upper end were two divisions for waltzing, forming two grand squares.(Grand Military Fete, 1814) The waltz couple dance is a phenomena we've investigated in previous papers, you might like to read our paper on The Regency Waltz and our investigation of The Waltz Medley dance for more information. The couple waltz was a dance that had arrived in Britain c.1800, it involved couples rotating clockwise together while progressing anti-clockwise around a circle (orAfter supper waltzing commenced, and continued with great spirit till seven in the morning(Ball at Weymouth, 1814) Grand Squareas per the floor chalking at the Military Fete). The dance form is described in British sources from around the year 1800, usually with an acknowledgement of controversy; 1814 seems to have been the tipping point after which it was increasingly considered to be acceptable within polite society. The celebratory mood of the year, coupled with the visit of the allied sovereigns, seems to have resulted in a more permissive attitude entering into the mainstream of the nation's dancing. The Waltz would continue to grow in popularity across the decade, the Burlington House balls of 1814 may have been the most important individual events with respect to the acceptance of the Waltz, they helped to shape the social dancing of the rest of the 19th century!

Three of the named waltzers at the Watier's club event were the 45 year old Duke of Argyll (1768-1839), the 22 year old Duke of Leinster (1791-1874) and the 24 year old Duke of Devonshire (1790-1858) (who was the owner of Burlington House). It was the 29 year old Countess of Jersey (1785-1867) who most most closely associated with the waltz however, we're informed that the dancing at the White's Club Ball was

The MinuetAfter his Excellency and her Grace had taken their seats, Minuets commenced(Queen's Birth Day Ball, Dublin, 1814) The fashionable dancers at the Burlington House events of 1814 danced the new and risque waltz, whereas the dancers at the Queen's Birth Day Ball in Dublin commenced their event with formal Minuet dancing - these two events represent the extremes of the social dancing spectrum. The minuet was an old fashioned dance, it was still danced at court but would rarely feature at the events of the nobility and gentry. Minuet dancers were expected to have perfected the graceful art of dance, they would have practised for much of their lives in order to cut a fine figure at a court ball. We've discussed the Minuet dance in a previous paper, you might like to follow the link to read more. Four ladies were to dance minuets at Dublin, each of them would be partnered by Sir Charles Vernon, the chamberlain to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. The implication seems to be that no other man could be found who was willing and able to dance the minuet at this date!

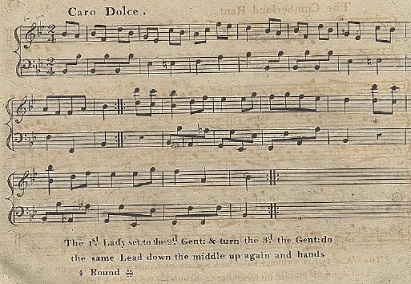

Caro Dolce Figure 15. Caro Dolce from William Campbell's 1806 21st Book. Image courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

Figure 15. Caro Dolce from William Campbell's 1806 21st Book. Image courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

... country dances commenced. The first was led off by Lady Emily Latouche and the Duke of Dorset, followed by about sixteen couple. The first dance was Caro Dolce ...(Queen's Birth Day Ball, Dublin, 1814)

Caro Dolce was a tune that was widely published in London between about 1806 and 1809. The origins of the tune are a little uncertain; the earliest reference I know of involves the publication of

The origins of the tune are uncertain though one clue does emerge; Kelly's Opera Saloon advertised (Morning Chronicle, 2nd July 1805) the music for O Dolce e Caro Istante, a song from Cimarosa's 1796 Gli Orazi e i Curiazi that was being performed at the King's Theatre opera house. It's possible that our tune was derived (at least by implication) from that song. The 1807 Maltese Melodies by Edward Jones described our tune as being a The tune was widely published c.1806. The precise chronology of publication is uncertain but the publications include: Campbell's 1806 21st Book, the Thompson collection of 24 for 1806, Skillern & Challoner's c.1806 1st Number, Goulding's c.1806 8th Number, Davie's c.1806 15th Number, Dale's c.1806 9th Number, Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 1st Book, Button & Whitaker's c.1806 2nd Number and Hodsoll's A Collection of the Most Fashionable Country Dances for the Year 1806. Later publications include John Paine's collection of 24 for 1807, Walker's c.1807 13th Number, James Platts' c.1808 7th Number, Monzani's c.1808 5th Number and Goulding's collection of 24 for 1809. The tune would also be referenced in both Edward Payne's 1814 Companion to the Ball Room and Thomas Wilson's 1816 Companion to the Ball Room. The tune was arranged in differing time and key signatures but it was the same tune throughout. The tune must have been somewhat popular but it didn't chance to be mentioned amongst the play lists of many society balls; it was danced at a Ramsgate ball of 1807 (Morning Post, 26th September 1807) and again at our ball of 1814. We've animated a suggested arrangement of Campbell's 1806 version (see Figure 15), of Hodsoll's 1806 version and of Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 version. For futher references to the tune, see also: Caro Dolce at The Traditional Tune Archive

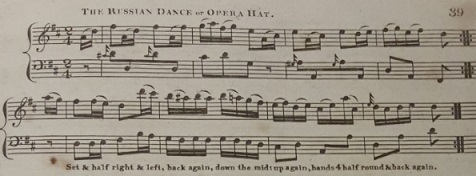

The Russian Dance / The Opera HatAmong the Country Dances were(Ball at Stratton, 1814)the White Cockade,the Russian Dance...  Figure 16. The Russian Dance or Opera Hat from Button & Whitaker's c.1809 13th Number. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.aa ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 16. The Russian Dance or Opera Hat from Button & Whitaker's c.1809 13th Number. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.aa ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Several tunes had been published over the decades up to 1814 under the name The Russian Dance, only one has any real claim to being the tune danced at the Stratton ball. Our tune, unlike the others, was widely published between 1809 and 1811; it was issued as The Russian Dance and also under the alternative title of The Opera Hat. It's not clear why it came to have two such different names. It makes thematic sense that the tune would see a popular revival in 1814 during the Tsar's visit, it was probably quite widely danced in 1814.

It's not possible to discover the precise chronology of publication of the tune, early examples include: Clementi & Co's c.1809 6th Number, Skillern & Challoner's c.1809 9th Number, Dale's c.1809 16th Number, Walker's c.1809 22nd Number, Wheatstone & Voigt's 1809 4th Book, Button & Whitaker's c.1809 13th Number, James Platt's 1809 11th Number and (under the unusual title of

The tune was also used at a medley of society events. It was recorded (Morning Post, 18th September 1810) that

John Parry published a new tune under the name of Opera Hat in the c.1810 4th volume of his Lyrist publication; this tune would go on to be widely published in other collections either as We've animated a suggested arrangement of Button & Whitaker's c.1809 version, of Skillern & Challoner's c.1809 version and of Dale's c.1809 version. For futher references to the tune, see also: Opera Hat (The) at The Traditional Tune Archive

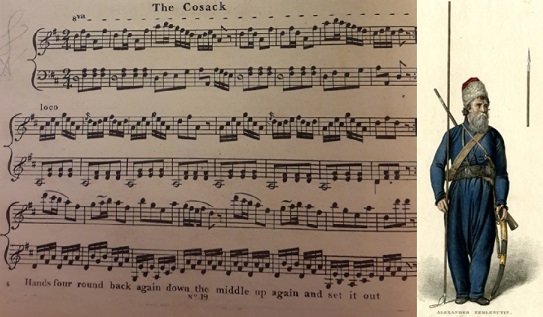

The Cossack...(Ball at Stratton, 1814)the Cossack...  Figure 17. The Cosack from Skillern & Challoner c.1813 19th Number (left) and a portrait of Alexander Zemlenutin (right). Left image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.925.o ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ; right image is courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 17. The Cosack from Skillern & Challoner c.1813 19th Number (left) and a portrait of Alexander Zemlenutin (right). Left image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.925.o ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ; right image is courtesy of the British Museum.

Many Cossack themed dance tunes circulated in London in and around the year 1814, it's difficult to discern which of them would have been danced at our ball. One candidate stands out as slightly more probable, that published by Skillern & Challoner in their c.1813 19th Number (see Figure 17), other candidates remain possible however.

London of 1814 had a fascination with the mysterious Russian warriors. It was claimed of several stage dances (with various degrees of accuracy) that they were

It was in 1813 that the Cossacks came to be especially celebrated in London. In the aftermath of Napoleon's retreat from Moscow in late 1812 the Cossacks (especially the Don Cossacks) were reported in the London press to be inflicting crushing losses on Napoleon's forces. The excitement reached a peak in April of 1813 when a pair of Cossack warriors came to be unwitting London celebrities; The Courier newspaper for the 9th of April 1813 reported

In late 1812 a further anecdote circulated in Britain, to some merriment, pertaining to the Cossacks. It was widely reported that Count Matvei Ivanovich Platov (1753-1818) (the officer who commanded the Cossack regiments) had: The tune at our ball is probably that published by Skillern & Challoner in their c.1813 19th Number as The Cosack (see Figure 17). Their tune is of the correct date and would go on to be republished in two further c.1815 collections as The Don Cossack (in Clementi's 24th Number) and as The New Cossack (in Hodsoll's 24th Number). It seems to have been the one of the few of the candidate tunes to be issued more than once (at least as far as I can discern), it was also the only such tune to be republished for country dancing in the aftermath of the 1815 Battle of Waterloo. We've animated suggested arrangements of Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1813 The Don Cossack Waltz, Falkner & Christmas's c.1813 arrangement of the same tune, Skillern & Challoner's c.1813 The Cosack and Clementi's version of the same tune.

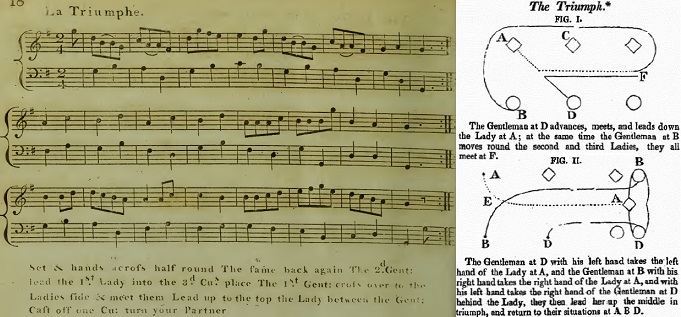

Le Triomphe / The Triumph...(Ball at Stratton, 1814)Le Triomphe,...  Figure 18. La Triumphe from Campbell's c.1794 9th Book (left) and the start of Thomas Wilson's explanations for the Triumph figure from his 1820 Complete System of English Country Dancing (right).

Figure 18. La Triumphe from Campbell's c.1794 9th Book (left) and the start of Thomas Wilson's explanations for the Triumph figure from his 1820 Complete System of English Country Dancing (right).

The Triumph is an example of an uncommon category of country dance, one in which a particular set of dancing figures became strongly associated with the same tune over many decades. For almost any other country dance, if it were published 10 times there would be ten different sets of suggested dancing figures attached to it; whereas The Triumph is associated with a single iconic leading figure in which one dancer is led up

Wilson described the figure in reasonable detail (see Figure 18); he explained that the 1st lady and 2nd man lead down the middle of the set while the 1st man crosses and passes behind the ladies such that all three meet below the third couple facing back up the set; the lst man takes his partner's right hand in his right hand, the 2nd man takes the 1st lady's left hand in his left hand, and the two men join their their remaining hands behind the lady, the three then lead home

The first publication of the tune, at least as far as I can discern, was in the Thompson collection of 24 country dances for 1790 under the name La Triomphe. The origins of the tune are uncertain but I note that several London stage productions of 1789 and 1790 featured the word The iconic leading figure wasn't part of that initial c.1790 publication, it would instead arrive shortly thereafter; publications that feature the figure include: Preston's collection of 24 for 1793, Campbell's c.1794 9th Book (see Figure 18), Preston's collection of 24 for 1799, Preston's collection of 24 for 1805, Dale's c.1805 6th Number, Walker's c.1808 17th Number, Thomas Wilson's 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore, James Platts's c.1809 10th Number and Thomas Wilson's 1816 Companion to the Ball Room. Publications without the special leading figure include Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 1st Book (2nd edition), Button & Whitaker's c.1808 8th Number, Fentum's collection of 24 for 1810 and Goulding's c.1810 17th Number. The tune was also mentioned in Edward Payne's 1814 New Companion to the Ball Room. The tune was also published a few times in Scotland (without figures), notably in Aird's c.1797 5th Volume and in Nathaniel Gow's c.1810 Morgiana publication; Mons Boulogne's 1827 Glaswegian The Ball Room publication also included a variant of the figures with the iconic lead. It's unusual to find a single tune remain popular over such a long period of time and for the same figure to be relatively consistently associated with it. We've animated a suggested arrangement of Campbell's c.1794 version (see Figure 18) and of Button & Whitaker's c.1808 version. For futher references to the tune, see also: Triumph (1) (The) at The Traditional Tune Archive

Mrs McCloudThe dancing commenced precisely at ten o'clock, by Colonel Doherty, leading off with the accomplished Mrs Schuyler, to the air of Mrs McCloud(Ball at Weymouth, 1814) It's very likely that the tune referred to as Mrs McCloud was the tune better known as Mrs McLeod of Rasay's Reel, a tune that we have studied in a previous paper. This tune was first published c.1809 and remained popular (in terms of both publication frequency and social references) through to about 1814, you might like to follow the link to read more. There was however a different tune named Miss McCloud's Fancy that was published in Campbell's 1795 10th Book, it's not impossible that this tune was still being danced 20 years later. The alternative tune is mainly known from Campbell, though it was also published in Longman & Broderip's collection of 24 for 1796 (where it was probably copied from Campbell's publication). It's rather more likely that the popular Mrs McLeod tune was being danced.

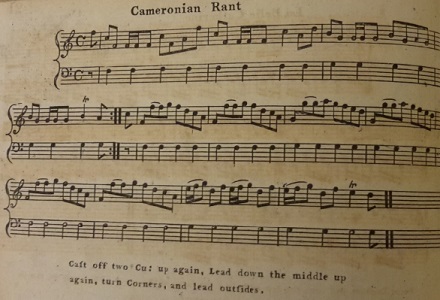

The Cameronian Rant... The Cameronian Rant &c. were kept up with the utmost cheerfulness till half-past one ...(Ball at Weymouth, 1814)  Figure 19. Cameronian Rant from Longman & Broderip's c.1791 Selection of the most favorite Country Dances, Reels &c..

Figure 19. Cameronian Rant from Longman & Broderip's c.1791 Selection of the most favorite Country Dances, Reels &c..

The Cameronian Rant is a veteran tune that had been published in London at least as early as the 1740s, it remained in print over many decades and evidently saw a resurgence of interest in the early 19th century. The earliest publication of the tune that I can confirm is within John Walsh's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1749; it can also be found in the c.1750 5th volume of Walsh's Caledonian Country Dances (which is otherwise known as Walsh's Caledonian Dances Volume 2, Part 1). It would go on to appear in both the c.1757 1st Volume of Thompson's Compleat Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances and in the c.1756 1st Volume of Rutherford's Compleat Collection of the most celebrated Country Dances. Publication of the tune then moved to Scotland where it appears in Neil Stewart's c.1761 A Collection of the Newest and Best Reels or Country Dances under the name The Cameronians Reel and the c.1761 11th volume of Robert Bremner's A Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances; it also appeared in Alexander McGlashan's c.1778 A Collection of Strathspey Reels (with several additional strains of music) and in James Aird's c.1782 1st volume of his Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs. It was then published in Joshua Campbell's 1789 A Collection of New Reels & Highland Strathspeys (with the additional McGlashan strains of music) and in John Anderson's c.1789 A Selection of the most Approved Highland Strathspeys, Country Dances, English & French Dances (as The Cameronian's Strathspey) and in Niel Gow's 1799 Part First of the Complete Repository of Original Scots Slow Strathspeys and Dances. The tune, as far as can be discerned, was first published in London and then went on to become popular in Scotland; it may have been the Gow interest in the tune (and the support of the Gow band in London) that triggered a fresh publishing interest in the early 19th century. Later London publications include: Longman & Broderip's c.1791 Selection of the most favorite Country Dances, Reels &c. (see Figure 19), one of Joseph Dale's c.1800 Selection of the most favorite Country Dances, Reels, &c publications and in Goulding's c.1803 3rd Number. It would then go on to be mentioned in both Edward Payne's 1814 New Companion to the Ball Room and in Thomas Wilson's 1816 Companion to the Ball Room. It was also published in Dublin in Cooke's New Dances for 1797 under the name The Cameronian Reel. The tune was evidently danced at a number of social events; in addition to our 1814 ball it was also danced at: Mrs Knox's 1802 Ball (The Courier, 9th April 1802); the Countess of Balcarras's 1804 Ball (Morning Post, 28th April 1804); an 1808 Masquerade Ball (Morning Post, 25th May 1808); the 1809 Perthshire Hunt Ball (Perthshire Courier, 9th October 1809); the 1810 Perthshire Hunt Ball (Perthshire Courier, 8th October 1810); an 1812 Ramsgate Ball (The Star, 10th October 1812) and also at an 1824 Batchelors' Ball and Supper (The Sun, 10th March 1824). We've animated a suggested arrangement of Longman & Broderip's c.1791 version (see Figure 19). For futher references to the tune, see also: Cameronian Rant (The) at The Traditional Tune Archive

ConclusionWe've investigated some of the major social events of the celebration year of 1814, especially those hosted at the palatial Burlington House; we've noticed in so doing that the Waltz couple dance was a prominent part of those celebrations. The summer of 1814 may have been a pivotal moment in the rise of the Waltz in London, the year from which the new dance form came to be widely adopted amongst the London elite. We've also studied several other events of 1814 from which a playlist of dances and tunes has been collected, if you would like to recreate a ball of 1814 then the tunes and dances we've investigated will be very suitable to use. If you have any additional information to share then do please Contact Us as we'd love to know more.

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved