|

Paper 53

Exotic English Country Dances of the late 18th Century

Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor

[Published - 3rd November 2021, Last Changed - 21st June 2025]

Notice: Undefined offset: 3 in /hermes/bosnacweb09/bosnacweb09ak/b1453/ipw.mgnotley/public_html/712/711header.php on line 720

Notice: Undefined offset: 4 in /hermes/bosnacweb09/bosnacweb09ak/b1453/ipw.mgnotley/public_html/712/711header.php on line 720

Notice: Undefined offset: 5 in /hermes/bosnacweb09/bosnacweb09ak/b1453/ipw.mgnotley/public_html/712/711header.php on line 720

Most of the English Country Dances published in Britain in the 18th Century followed a reasonably consistent formula, a tiny minority however were genuinely different. In this paper we'll review some of those unusual and exotic Country Dances of the late 18th Century that defied the trends. Together these dances hint at a slightly more diverse social dancing experience having existed in the past than might otherwise be thought, some dancers were evidently willing to experiment.

Figure 1. William Hogarth's c.1745 The Country Dance, part of an unfinished series about a happy marriage.

The dances we'll consider further in this paper are:

- A.D.'s New Country Dances, 1764 (Complex 2 and 3 couple sets)

- Roger of Coverly, c.1764+ (A stretched Country Dance)

- F.P.'s Divertimentos, 1772 (Becket formation Country Dances)

- Southern's Country Dances, 1773 (Country Dances

in the Manner of Cotillons , also 4 couple dances)

- Fishar's British Guards, 1778 (A 10 couple dance)

- Le Boulanger, c.1780+ (A round dance)

- Skillern's Caledonian Medley Dance, 1787 (A medley of tunes for the same figures)

- Platts's La Mêlange, 1791 (A triple progression medley)

- Metralcourt's The Sportsman, 1793 (A quadruple minor)

Typical Country Dances of the late 18th Century

We should first consider what was conventional in the Country Dancing industry of the 18th Century, we can then go on to consider what was atypical and unusual. Most of what we know of Country Dancing prior to the the 18th Century derives from study of the Country Dance publications of John Playford (1623-c.1686). Playford, and his successors, issued some 18 editions of a book named The English Dancing Master (later simply The Dancing Master) between 1651 and around 1728. Each new edition would see new dances added and some of the older dances removed. Early editions included a greater variety of dance forms than the later editions, this included square dances, non-progressive dances and round dances. As time went by the dance form simplified into the ubiquitous longways set. A greater number of publishers became involved in publishing such dances over time. The early and mid 18th Century saw several music sellers issuing annual collections of longways Country Dances, this included the likes of John Walsh, Peter Thompson and David Rutherford. Dances (at least as published) of this era tended to be simpler than those of the Playford era.

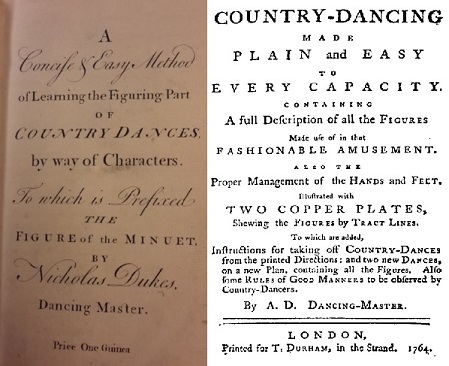

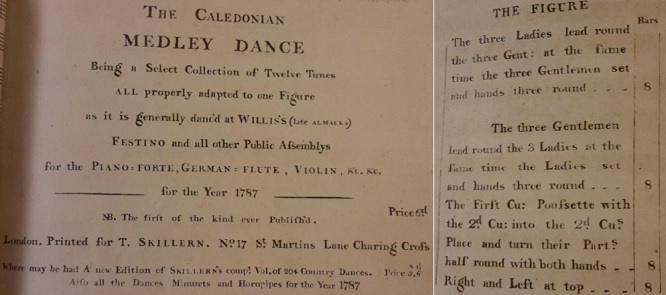

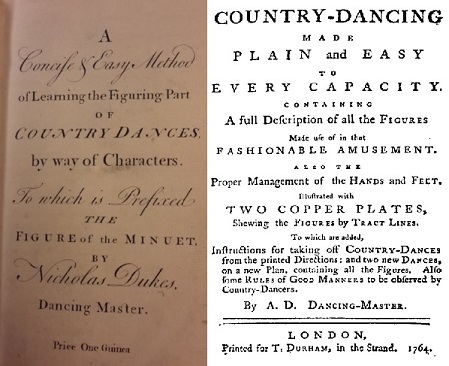

The mid 18th Century also saw the publication of two important books about Country Dancing, these two works are incredibly important to the modern study of Country Dancing, they offer a fascinating wealth of detail beyond what can be gleaned from the published dances themselves. These two important books were the 1752 A Concise & Easy Method of Learning the Figuring Part of Country Dances by Nicholas Dukes (see Figure 2, left) and the 1764 Country Dancing Made Plain and Easy by an anonymous dancing master who published under the initials A.D. (see Figure 2, right). It's unlikely that either work was influential when first published, they probably enjoyed a small and localised readership, their value to modern scholarship is tremendous however. They enable modern readers to analyse dances published in the mid 18th Century and reconstruct them using authoritative supporting information. Both works attempted to document Country Dancing of their respective dates in an encyclopedic level of detail; neither achieved that (as a modern reader significant questions remain unanswered) but if we want to reconstruct historical dances as they'd have been understood when first published then these works help enormously.

Nicholas Dukes was a dancing master based in Pater-noster Row, Cheapside, London between at least 1749 (General Advertiser, 9th October 1749) and 1767 (Public Advertiser, 1st August 1767). He offered to teach Grown Gentlemen country dancing at his Long Rooms there. He issued many advertisements over this period, most after 1752 mentioned his book. For example in 1753 (Public Advertiser, 22nd September 1753) he advertised:

Figure 2. A Concise & Easy Method of Learning the Figuring Part of Country Dances by Nicholas Dukes, 1752 (left) and Country Dancing Made Plain and Easy by A.D., 1764 (right).

Grown Gentlemen or Ladies may be taught a Minuet, or the Method of Country Dances, with the modern Method of Footing, in so private, genteel and expeditious a Manner, as to render them very soon capable of performing in the politest Assemblies. Mondays and Wednesdays being the Nights for practising of Country Dances, there's a compleat Set of Gentlemen only, which assembles for that Purpose.

And for the quicker Improvement of such Gentlemen, who are desirous of learning the figuring Part of Country Dances, in a more expeditious manner than common; I have laid down such a Plan, by a little Book, which I have printed and published by Authority, wherein is explained the most principal Figures of Country Dances, with the Figure of the Minuet annexed thereto. These Figures are so trac'd that by just casting your Eye on them, you'll see them form'd in the manner they're to be done. By this method, with a little Instruction, and Person may improve themselves without the Presence of a Master; and as to Gentlemen that travel, it will be of infinite Use to them, by Reason, if they chance to forget for Want of Practice, by turning to this, they may immediately set themselves to rights; and that every Person who is desirous of being qualified as above, should not be without so useful a Guide, I have reduced the Price to the easy Rate of half a Guinea; as every Person may be assured, that the Book will answer the above Descritpion, I shall leave them to consider and Judge of the Utility of it.

Nicholas Dukes wrote principally of the figures used in Country Dancing, he also advocated that anyone with pretensions to gentility first master the Minuet before learning the Country Dance. The elegance required of the Minuet would serve the dancer well within a Country Dance. He wrote very little on the form of the Country Dance however, most of his effort was invested in describing the figures.

A.D. also wrote of the figures used in Country Dancing but went further and also wrote of the form, style and etiquette of Country Dancing. The Use of the Feet was explained to involve nothing more than a step forwards, and a hop, or rather a little slip, of the same foot, by an easy spring along the floor; this done to the time, first with the one foot and then with the other, alternating, beginning with the right . The Use of the Arms explained the differences between Leading, Drawing and Swinging , together with such variations as the Arm-in-arm and Galloping forms of movement. A.D. then went on to describe the standard longways form of Country Dancing. The top-most or first couple were described as having the full liberty to chuse what dance they think proper, which is called Leading down , and the pattern by which a new minor set forms as the first couple progresses down the dance was also described. The concept of certain figures ending improper was also described though all complete dances must end Proper . A.D. defined the concepts of duple and triple minor dances, albeit with different terminology: dances requiring but two Couple to perform them, are called single dances ... dances, requiring three Couple to perform them, are called double dances . A further gem to be found within A.D.'s book are the rules of good manners to be observed by Country Dancers , we've written of them elsewhere, you might like to follow the link to read more.

What we read in the works of Dukes and A.D. is consistent with what can be found in the typical Country Dance collections of the period. People in general were dancing longways sets (for as many as will ), they danced in minor sets of 2 or 3 couples, dancers began proper with gender based sides to the dance, the leading couple would select the figures to dance and etiquette conventions would dictate what behaviour was acceptable or required at the various assemblies around the country. There was plenty of room for variation but the general experience would be fairly consistent. The subsequent decades of the 18th Century would see the Country Dance evolve (especially under the influence of the Cotillion dance in the 1770s), but the general form remained largely unchanged into the 19th Century. If you would like to read more about the form of the Country Dance in the early 19th Century then that's something we have written about elsewhere.

If we consider the early 19th century then several new variations in Country Dancing would go on to be documented, some more popular than others. Examples include the Waltz Country Dance, the Spanish Country Dance and a range of hybrid dances including Ecossoises, Swedish Country Dances and Circular Country Dances. These 19th Century innovations offer evidence that dancing masters, at that time, were willing to experiment with the general form of the Country Dance. It seems likely that this had always been true and that dancing masters of earlier decades were equally willing to experiment, we simply have more evidence to draw upon at later dates. This paper will consider some of the more peculiar Country Dances from the later 18th Century that were in fact published, thereby offering some supporting evidence in favour of the diversity theory.

We will now consider some examples of convention defying dances.

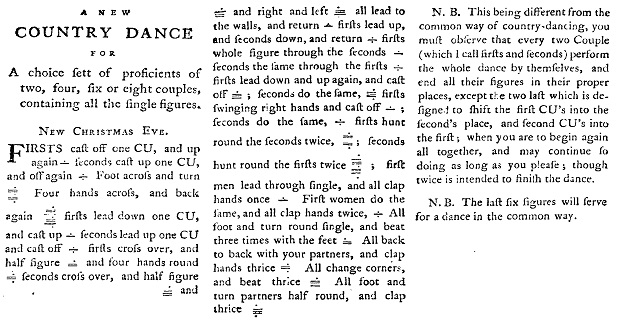

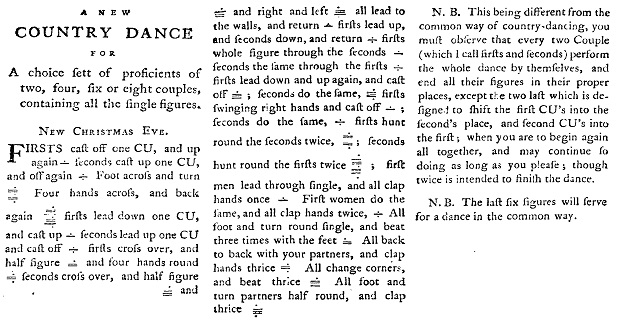

Figure 3. New Christmas Eve from A.D.'s 1764 Country Dancing Made Plain and Easy.

A.D.'s New Country Dances, 1764 (Complex 2 and 3 couple sets)

The first of the Country Dancing novelties that we'll study are actually found towards the back of A.D.'s 1764 Country Dancing Made Plain and Easy. Two Country Dances were published there, together with their music, which are unlike any I've seen published anywhere else. The first was named New Christmas Eve (see Figure 3) and was described as A new Country Dance for A choice sett of proficients of two, four, six or eight couples, containing all the single figures . The second was named New Twelfth Night and was described as being Another for Three, six, nine, or twelve couple, containing all the Double Figures . These dances demonstrated that it would be possible to dance all of the figures described within the book within a single dance, either for two couples or three couples depending on the figure. The result is a pair of very long and improbably complicated dances arranged to simple tunes.

The dances are, to say the least, challenging. They're described as being for a choice sett of proficients thereby indicating that they're not for the general public, it seems unlikely that they'd have been danced anywhere beyond A.D.'s own academy. They do appear in print and thereby demonstrate that dancers somewhere might plausibly have attempted to dance them, it's unlikely that they'd have been danced socially however. These dances don't modify the standard form of the Country Dance, they simply combine so many figures into a single routine that no dancer could reasonably be expected to remember the sequence. We've animated a suggested arrangement of New Christmas Eve, it involves 120 bars of music to a single iteration of the dance; after this marathon iteration the first couple will have progressed one position and the dance will start again.

New Christmas Eve is a dance for two couples, or a multiple thereof. The instructions note that every two Couple (which I call firsts and seconds) perform the whole dance by themselves, and end all their figures in their proper places, except the two last which is designed to shift the first CU's into the second's place, and second CU's into the first; when you are to begin again all together, and may continue so doing as long as you please; though twice is intended to finish the dance . This dance is arranged for multiple groups of two dancers who end the dance having swapped places. If there are more than two couples dancing then they all simultaneously perform the same dance in groups of four. This is deceptively important: the dance does not involve the normal progression for a Country Dance, couples simply swap places and then return in the second iteration so that the dance can end. Two iterations of the dance are intended to be sufficient, it's effectively a two-couple dance.

This concept extends to New Twelfth Night where every three CU perform the whole dance by themselves, and by the last two figures all three change places, viz. seconds are now firsts, and thirds are seconds, and firsts are thirds: this may also be done as often as you please, but by doing it three times, each returns to their proper places, which is intended to finish the dance . A.D. had effectively invented, for this dance, the concept of a Three Couple Set ; or, if not invented , then at least documented as a convention that might plausibly have been employed by other dancing masters of the mid 18th Century. This dance is the only evidence I know of for the use of the 3 couple sets in the 18th Century. Logic suggests that 3-couple sets would have been useful when teaching country dancing in an academy, perhaps also for social use amongst a small group of friends. The historical sources tend only to refer to the longways formation however; such dances involve any number of couples dancing, the first couple will remain a first couple throughout many iterations of the dance (that is, duple or triple minor dances).

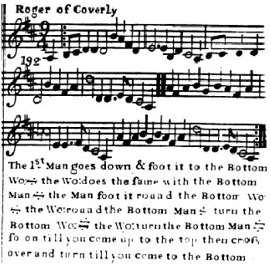

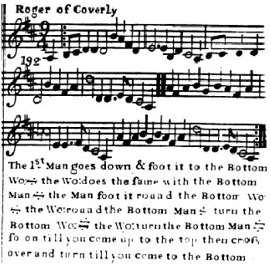

Figure 4. Roger of Coverly from Thompson's c.1764 Compleat Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances, Vol 2

My suspicion is that these dances were used by A.D. when teaching country dancing in person. Perhaps the figures would be announced by a prompter (in the modern sense where figures are called out mid-dance) and the scholars would perform what they heard. It seems improbable that they could be used in any other context. They're a fascinating insight into the liberties that might be taken with the form of the Country Dance by a professional dancing master, especially in the privacy of their own academy.

Roger of Coverly, c.1764+ (A stretched Country Dance)

Sir Roger de Coverly is a unique dance that we've written about before. We'll not repeat most of that information here, you might like to follow the link to read more. The music for Roger dates back to the end of the 17th Century, an important innovation was published c.1764 however, that's what causes the dance to be included within our list here.

At some point during the 18th Century a unique dance came to be associated with the tune, the earliest variant of which (as far as I know) was published in Thompson's c.1764 Compleat Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances, Vol 2 (see Figure 4). The figures for this dance defied the standard conventions for a Country Dance; normal Country Dances restricted the dancing to a minor set of two or three couples, this dance involved the entire longways set in every iteration. The figures begin with the leading man going down the entire length of the dance to meet the bottom most lady, if the distance to travel was great then this might require more music to perform than might otherwise be expected. The subsequent figures were of a similar minor-set defying nature.

The dance went on to be republished many times over in several distinct variations. One early 19th Century publication advised that the strains of music should be played in a loop until the dancers have interacted with everybody in the set (that is, the musicians must watch the dancers and change what they're playing only when the dancers are ready). If that advise were followed then it would make for a unique experience.

The dance would continue to evolve over the late 18th and early 19th centuries, it would become referred to as a finishing dance in Regency Britain (a mixer dance for the end of an event). It was clearly danced, and enjoyed, despite defying the conventions. Indeed, it seems to have been celebrated for defying the conventions of a typical country dance. The abiding mystery is why so few other dances were granted a similar privilege, Sir Roger stands almost alone as a popular Country Dance that actively defied the standard conventions.

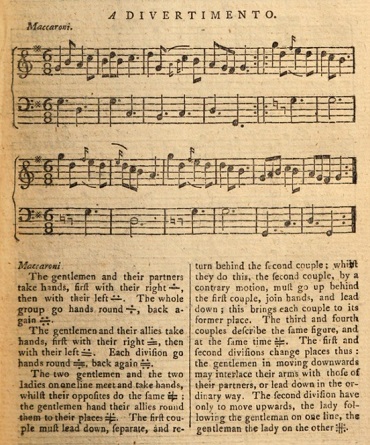

F.P.'s Divertimentos, 1772 (Becket formation Country Dances)

The next dances we'll consider were published in 1772 by another anonymous dancing master, this time under the initials F.P.. It's quite possible that F.P. was in fact the Scottish dancing master Francis Peacock (1723-1807), Peacock would go on to publish an especially important book named Sketches Relative to the History and Theory, but More Especially to the Practice of Dancing in 1805. Any such identification remains speculative however.

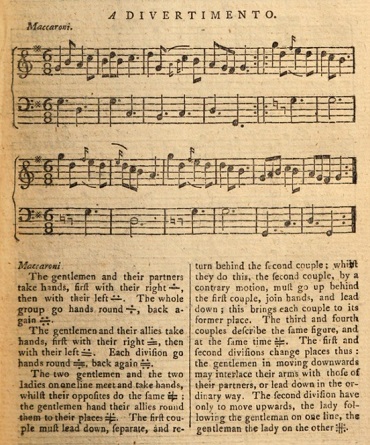

Figure 5. Maccaroni by F.P. in The Lady's Magazine, Vol III for the Year 1772.

F.P.'s dances of 1772 were named Divertimentos and were published in the third volume of The Lady's Magazine under the title A new Kind of Dance over four pages (see Figure 5). The abnormal feature of the dances was that every second couple would stand improper (the man on the ladies' side of the set, the lady on the men's side) such that each dancer would have someone of the other gender on each side and across from them. This arrangement of a longways set would go on to receive the name Becket Formation in the 20th century (though as we'll see in a moment, it's not a Becket formation dance in the normal sense of the term).

F.P. explained in a letter to the editor that I have sent you two new dances, which I shall call Divertimentos , in which I have studied to unite the common country dance with the Cotillon. . It continued: as in cotillons of two lines, the gentlemen at the top must have a lady next to him, the lady a gentleman, and so on alternately on both sides, from the top to the bottom. By this arrangement, each gentleman not only has his partner opposite to him, but in turning to either hand he may have the pleasure of being engaged with a lady. . Next the terminology of the dance was introduced. Every four couples in the longways set, from the top, would be divided into groups and each group into two divisions of two couples each (men diagonally opposite to each other, ladies diagonally opposite on the other corners). The progressive nature of the dance would cause the two divisions within each group to switch places, each would thereby meet a new division from the other direction and form a new group for the next iteration of the dance. Progression was therefore very similar to that of a normal country dance except that two couples would progress together either down or up the set. Upon reaching the bottom of the set the division must wait one revolution of the dance before they can be engaged again. Should there be an odd division at the foot of the dance, it cannot be engaged till after the first revolution of the dance . One final new term was introduced, that of allies . An ally being the person to the side of each dancer within a division .

Readers may have noticed that the dance described does not follow the typical pattern of a modern Becket formation Country Dance. A typical 20th century Becket would have partners stood side by side (in the position F.P. described as being that of the ally ) and progression would tend to be clockwise around the Set (couples move down the ladies' side of the set and up the men's side). The Divertimentos dance has the same starting position as a Becket but the progression is simpler. F.P. described the dance as being influenced by cotillons of two lines ; a typical Cotillion dance was in the form of a square with a pair of dancers on each edge, a Cotillon-of-two-lines was a variant in which two couples stand side by side. The Cotillon-of-two-lines was not widely published in Britain though examples were certainly known, an example being the c.1770 Le Vainqueur by Mr Siret.

F.P. acknowledged that the dance form could be confusing: Should any of my fair country-women find their ideas bewildered by my descriptions of any of the above figures; if they will but take the trouble to cut two or three cards, with black and red spots, into small bits; or get backgammon men, and place those of one colour for gentlemen, and those of the other for the ladies, by making the proper movements with them, they will perfectly comprehend my meaning. Two example Divertimento dances were published named Maccaroni (see Figure 5) and The Pantheon; we've animated a suggested arrangement of these two dances, I hope they will assist the modern reader's comprehension to a greater extent than moving backgammon pieces around will do so! It might be noted that the tune given for Maccaroni is essentially that of Purcell's 1686 Lillibullero.

I've no evidence of these Divertimento dances being enjoyed socially, or even of further examples being published. They seem rather to have been an experiment that F.P. hoped that someone somewhere might enjoy. They do however offer evidence that there were dancing masters prepared to be creative with the form of the country dance in the 1770s.

Southern's Country Dances, 1773 (Country Dances in the Manner of Cotillons , also 4 couple dances)

A dancing master named Vernon Southern of Hull published a collection of dances in 1773 named Twenty Four Country Dances in the manner of Cotillons. His collection is unusual for several reasons: he introduced Cotillion dancing steps into English Country Dancing, arranged his dances so that everyone in a longways set could commence dancing at the same time, he even employed Cotillon figures within his Country Dances. Every one of these novelties is worthy of further consideration.

Of particular note are two dances within his collection arranged for four couple minor sets. After each iteration of the music both the First Couple and Fourth Couple progressed a space. This form of progression is particularly unusual. We've written more of this unusual collection of dances in another paper, you might like to follow the link to read more.

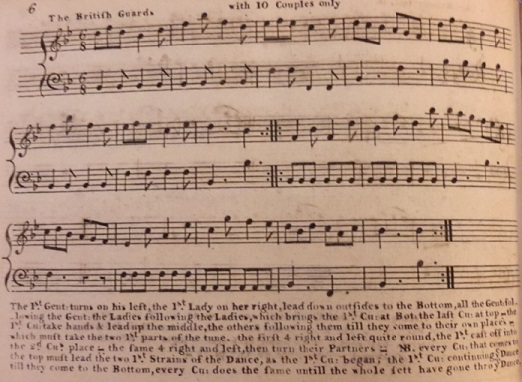

Fishar's British Guards, 1778 (A 10 couple dance)

Our next dance is another oddity, this time published by James Fishar in his 1778 Twelve New Country Dances, Six New Cotillons and Twelve New Minuets. It's a County Dance that was arranged specifically for ten couples and was named The British Guards (see Figure 6). The publication date for the collection wasn't included on the cover of the work, it can however be dated to 1778 as Fishar advertised the collection as being new in The General Advertiser for the 5th of March 1778. That advertisement is rather interesting and so is reproduced here in full, it reads:

Figure 6. The British Guards by James Fishar from his 1778 Twelve New Country Dances, Six New Cotillons and Twelve New Minuets. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, a.9.b.(4.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Now are published, Twelve new Country Dances, with Six Cotillions, calculated on purpose for those ladies and gentlemen who do not understand the steps. The music composed, and the figures adapted by James Fishar, for ten years first dancer, ballet-master, and head teacher of all the dancing at the King's Theatre, London. To which is added, Twelve new Minuets: the whole with a thorough bass for the harpsichord. Mr Fishar, being convinced that many ladies and gentlemen do not like to dance cotillions, on account of being obliged to learn the steps. Mr Fishar thought himself bound in gratitude for the many favours he has always received from the public, both in his capacity of first dancer, ballet-master, and in all his publications, to find out a method for them to dance now those kind of dances, without any steps but the common country dance steps, which nobody has attempted before; and if this meets with their approbation, he will not spare pains nor trouble to furnish them every year with a new set of them, so easy as to be understood at one view. Price two shillings and six-pence. To be had of Mr Rutherford, at his music shop in St. Martin's-lane; and all the music shops in London.

Mr Fishar begs leave to inform the ladies and gentlemen, that he has taken all possible care to make the country dances the most easy ever published.

The collection of dances was issued by one of the most prominent dancers in London, Fishar claimed to have paid great care and attention to their creation and had simplified them to be of use to even the least proficient of dancers. He went so far as to claim that the Country Dances in the collection (which would include The British Guards) were the most easy ever published . It's uncertain whether anyone outside of Fishar's immediate sphere of influence would have danced these dances, presumably Fishar himself would have taught them to the public when opportunities to do so arose. Fishar listed some 111 Subscribers to his book, including amongst them the Duke and Duchess of Richmond, he evidently had some influential patrons who must have enjoyed his dances.

The British Guards is unusual principally because it is arranged to be danced with 10 couples only . We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance for just six couples. The initial figure involves all ten couples leading up to the top of the set, casting off and leading down, then casting up and leading back to their initial starting positions. The remainder of the dance is an ordinary (perhaps even boring) figure for the top two couples which results in them changing places. A single iteration of the dance ends with the original 2nd couple at the top of the set and the original first couple in their place. Fishar explained the progression as follows: NB. every Cu: that come to the top must lead the two 1st Strains of the Dance, as the 1st Cu: began; the 1st Cu: continuing ye Dance till they come to the Bottom, every Cu: does the same untill the whole sett have gone thro ye Dance . Fishar may have attempted to make his dances intelligible to everyone but I myself find this instruction confusing. If the second couple were to lead off the second iteration of the dance then it would end with the top two couples swapping places for a second time and restoring all ten back to their initial positions, that doesn't make sense. I suspect Fishar intended the original second couple to lead off the second iteration of the dance and the final 16 bars to be danced by the original first and third couples. Over nine iterations of the dance the original second couple would lead the first figure each time and the original first couple would progress to the bottom of the set. Then the original second couple would lead off in their own right to be replaced at the top by the original third couple. If I've understood this correctly then the entire dance would require ninety iterations of the music to dance through completely! This may seem a staggeringly large number to a modern audience but it was not uncommon for Country Dances of this period.

The dance is somewhat similar to Sir Roger in that all the couples in the entire Set are involved in each iteration of the dance. This is in stark contrast to the many thousands of other Country Dances that were published and which restricted the dancing to a minor set of either two of three couples. It demonstrates once again that some dancing masters were willing to experiment with the form of the Country Dance. Fishar evidently did so in a collection he aimed at the least sophisticated of dancers.

Le Boulanger, c.1780+ (A round dance)

It's debatable whether our next dance should be considered to be a variation of the English Country Dance at all, it was sufficiently different to almost any other dance that it might be considered a unique dance form in its own right. Its name is Le Boulanger, it's a dance that we've written about elsewhere, you might like to follow the link to read more. The earliest known versions of this dance were published in Paris, perhaps as early as 1740, it is an unusual French Country Dance.

At least two dances named Le Boulanger were published in London c.1780, one by Thomas Budd and the other by Francis Werner. I don't have a copy of Budd's publication to refer to, Werner's dance was really quite interesting though. Werner's directions indicate that any number of couples may dance it, they were to form a circle (standing side-by-side, as in a Cotillion). The dance starts with everyone circling around and back again; this is followed by a sequence of turns in which the first man alternately turns the next lady in the circle, then his parter, all the way around the circle. Everyone then circles again, followed by the first lady alternately turning each man and her partner around the circle. Each couple repeats this sequence around the entire circle.

This is another dance that would go on to be even more successful later in the century, it would go on to be a favourite dance in Regency London. As with Sir Roger de Coverly it's a dance that caused all of the dancers to interact with each other, it also ensured activity for each dancer in every iteration of the dance. We've animated a suggested arrangement of Le Boulanger here.

Before moving on I'll quickly point out that other variations on the standard Cotillion or French Country Dance formations were also being danced in Britain. Examples include Cotillion dances arranged for just two couples (which were referred to as quadrilles at this early date), or for 16 dancers, or arranged in straight lines (as referred to by F.P. above). There was a standard formula for the French Country Dance, just as there was for the English Country Dance, but there was also room for variation.

Figure 7. The Caledonian Medley Dance by Thomas Skillern, 1787. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.49.e.(2.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Skillern's Caledonian Medley Dance, 1787 (A medley of tunes for the same figures)

The next dance we'll consider is a simple Country Dance in an unusual musical arrangement, as published by Thomas Skillern in 1787. Skillern (d.1800) was one of London's music sellers, we've written about his nephew (also named Thomas Skillern) in another paper. He issued a unique publication named The Caledonian Medley Dance for the Year 1787 (see Figure 7) which documented our dance. He described the contents as Being a Select Collection of Twelve Tunes ALL properly adapted to one Figure as it is generally danc'd at Willis's (late Almacks), Festino and all other Public Assemblys . He then added NB. The first of the kind ever Publish'd . The contents are twelve 32 bar tunes, in a variety of time signatures (2/4, 4/4 and 6/8), all arranged to the same dancing figure. Several observations emerge from Skillern's description of the dance.

Skillern's implication was that he had documented the experience of dancing at the fashionable Assembly Rooms of his date. Most dance publications at this date would make a similar claim of course, Skillern's text could be considered hyperbole, it was more detailed than most however. Other publishers might claim that their works were as danced at Almack's or similar, thereafter the contents would follow the conventional formula for Country Dance collections. Skillern asserted that his tunes were adapted to one Figure as it is generally danced at... , he was not only making a claim of accuracy but also publishing something exotic and otherwise unknown (it was the first of its kind in his own words). The music itself was printed in a higher quality format than would be expected of the cheaper publications, a bass accompaniment was included for each tune. The entire work appears to be of a good quality, the dancing figures are explained in better detail than was normal at the date. It's likely that he really was attempting to satisfy (or perhaps create) a demand for a new type of dance publication.

The next thing to note is that the collection was described as being a Medley . The word medley relates to the music in this context, not to the dancing figures. The twelve tunes (each of which were individually named) being quite different from each other. My suspicion is that the tunes were intended to be played in sequence, the dancers would continue dancing the same set of figures as one tune merged into the next mid-dance, altering their steps as required when switching from one rhythm and tempo to the next. There is an element of uncertainty here and other explanations of the dance form are of course possible. Individual Country Dances could be performed for upwards of an hour at this date, some dancers were liable to find them dull. Perhaps the elite assemblies could make the experience more rewarding by encouraging, or at least tolerating, this musical variation. Quite how the music would flow from one tune to the next is unclear. Maybe the musicians would play the first tune for a few iterations and then pause, extending a single note playfully as the dancers hovered, then surprising the company by launching into a quite different tune to resume the dancing. One can almost imagine a playful young Duchess, when asked to call a dance, cheekily asking the leader of the orchestra to surprise her with a medley of tunes; and so a new convention may have been born.

The next thing to note is that the collection of tunes was described as being Caledonian . That is, Scottish. Several were indeed of Scottish origin, others are of uncertain provenance, one is even named The Walse (though this was not a Waltz tune in any normal sense of the word, indeed, it's the first musical reference to the word Waltz that I'm aware of in any British musical publication). The word Caledonian may instead refer to the concept of a medley rather than to the origin of the named tunes. Scottish dance collections routinely issued medleys combining a single Reel with a single Strathspey tune at this date, they were presumably intended to be danced in combination. London's dancers may have taken that concept and extended it to a dozen tunes in a single medley; indeed, our hypothetical young Duchess may have been Scottish herself, perhaps she was in London for the Westminster season.

Medley dances may have been commonplace in late 18th Century London, it's difficult to know. This is the only publication I'm aware of to have attempted to document them (except for our next example below), any such convention may therefore have been isolated and of short duration. The implication that medleys were being danced at Almack's and the Festino gatherings at Hanover Square is fascinating, it hints once again that the social dancing conventions may have been more flexible than we might otherwise have imagined.

Platts's La Mêlange, 1791 (A triple progression medley)

Our next dance is a second example of a medley dance, this time arranged in a very different way to Skillern's example. It was published by James Platts as his 1791 La Mêlange single sheet publication (which was registered for copyright purposes at Stationer's Hall on the 2nd of January 1792, see Figure 8). We've written about James Platts (and this dance) in a previous paper, you might like to follow the link to read more. The work was subtitled Longways for as many as will, or the New Medley .

The Platts dance was once again arranged so that several different tunes would be played in immediate succession. Platts selected four tunes that he named as English (in 2/4 measure), Irish (in 6/8 measure), German (in 3/8 measure) and Scotch (in 4/4 measure). His arrangement placed the four tunes in a single continuous score. A footnote at the bottom of the document explained that This Tune may be danc'd with any single Figure , this suggests that dancers could repeat Skillern's technique and select a basic figure sequence and repeat it through each of the tunes in the medley, if they wished to do so.

Platts went further however. For his medley he choreographed a complicated set of figures that would extend over the entire musical sequence, each iteration of this dance would involve all four tunes in their various different time signatures. The result is somewhat reminiscent of A.D.'s New Twelfth Night above. The Platts arrangement is especially noteworthy for involving a triple progression of the leading couple, at the end of the four tunes they will be in the 4th position such that a new minor set can lead off behind them. It's very unusual to find a published Country Dance with more than a single progression arranged within it, on the rare occasions that they are encountered there's often an assumption of error; Platts leaves us in no doubt, he ended his figure sequence after a triple progression: ... which brings you down 3 Cou: .

This dance is complicated. That it was being sold as a stand-alone publication (rather than within a larger work) is fascinating, Platts must have thought there would be a market for this type of publication. It may have been an experimental work of course. Platts was operating at the leading edge of several new dance trends; for example, at this c.1790 date he was pioneering the use of Waltz rhythms in Country Dances (he published several examples before almost anyone else is known to have done so). His publications may have been popular amongst the more adventurous of London's social dancers. Once again we have found a clue that medley dances may have been danced in London towards the end of the 1780s and start of the 1790s, this time we also have clear evidence of multi-progression dances being experimented with too.

We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance in four parts: Part 1 (English), Part 2 (Irish), Part 3 (German), Part 4 (Scotch).

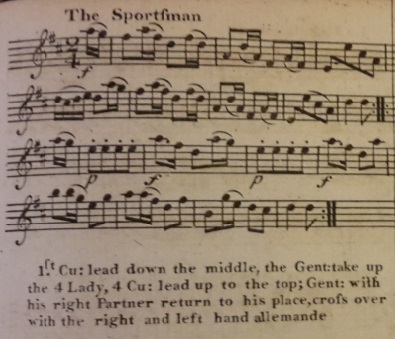

Metralcourt's The Sportsman, 1793 (A quadruple minor)

Figure 9. The Sportsman by Charles Metralcourt from his 1793 Twenty Four Country Dances. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.55.(7.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Our next dance was published by Charles Metralcourt in his 1793 Twenty Four Country Dances, they were (according to the cover) humbly Dedicated by Permission to His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales . The date of publication wasn't recorded on the cover of the work but they can be reliably dated to 1793 by way of the copyright register at Stationer's Hall. Charles Metralcourt (c.1739 to 1814) was a Bath based dancing master for most of his career, he may have enjoyed significant influence amongst the visitors to the Spa. This publication is the only collection of dances that he is known to have produced, they were probably danced at his academy (and potentially elsewhere too). He evidently had sufficient access to the social elite to have dedicated his collection by permission to the Prince of Wales, it's unclear whether the Prince would ever have met him in person, perhaps some intermediary had made the necessary connections. Metralcourt put his name to the collection, he was evidently proud of the dances he had composed and considered them to be of a high quality.

One of the dances in the collection was a little unusual, it is named The Sportsman (see Figure 9). The rest of the collection was made up of a fairly typical set of Country Dances, The Sportsman only differs in so far as the dancing involved an unusual figure and a fourth couple. The thousands of other Country Dances published in our date range invariably involved either two or three couples in a minor set, this dance involved four. It could be argued that this dance was published with a typesetting error present and that it should have involved only three couples, it could certainly be danced with only three; but (as noted above) Metralcourt was an eminent dancing master and he dedicated his collection to the Prince of Wales, mistakes shouldn't have been made. The reference to a fourth couple appears twice within the text, if it was a misprint then the mistake occurred twice. The existence of this dance hints that the social dancers at the Bath Assembly Rooms would not have been concerned or surprised by a quadruple minor dance should it have been encountered, they would perform it just as easily as they would accept a slightly exotic dancing figure.

The exotic figure from this dance involves the leading couple dancing down the set and the man exchanging his partner for the fourth lady, he then returns to the top of the set with that new partner. The new 4 Cu then lead up the set and swap the ladies once again, the original fourth couple return to their original places. It's unusual for involving the fourth couple, for swapping (albeit temporarily) partners, and for requiring activity from an otherwise inactive couple. Presumably a new minor set would be formed at the top of the dance every fourth iteration of the music. We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here. The dance itself is nothing particularly special, it is however evidence that dances might be encountered that played with the standard formula; a leading couple could call a dance with figures such as these and the company would probably have tolerated that.

Conclusion

London's Country Dance collections of the later 18th century tend to be formulaic, the dances were single progression duple or triple minors in a conventional arrangement. Dance historians often summarise this period as one of simplification. Much of the novelty to be experienced in Country Dancing was found in the seasonal cycle of new tunes becoming popular, not in the dance form itself.

This paper has demonstrated that some dancers of the later 18th Century would have experienced novelty in the dance hall. Some dancing masters were willing to experiment with the format of the dance. The experience in the Assembly Rooms and Ballrooms of the nation would not have been universally the same, even though the bulk of the music publishing industry issued formulaic dance collections. That's not to suggest that there was a great degree of variety of course, the dances we've studied in this paper were exceptional, they don't disrupt the broader trends. What remains uncertain is the extent to which variety was encountered, perhaps variety tended not to be recorded?

One of the challenges when investigating an unusual historical Country Dance is the question of quality. If a Country Dance (as published) seems not to work then the modern arranger of the dance may seek an exotic explanation; whereas, the cause may be better explained by the original publisher having paid insufficient care and attention. The dancing master Thomas Wilson wrote of the poor quality that many such collections exhibited in his books of the 1810s. The dances we've reviewed in this paper are especially interesting as there is little doubt about their quality, the dances genuinely were arranged to be unusual. We can't dismiss them as being erroneous at source.

If we were to consider the early 19th century then a greater variety of Country Dance variants would emerge, we've written about many of them before. Examples include Mr West of Derby who mentioned (Derby Mercury, 4th July 1805) his improved method of dancing Country Dances, wherein the inconvenience of waiting for the first couple's coming down is obviated, and the whole company are in motion at once ; Edward Payne's c.1815 Spanish Country Dances or Thomas Wilson's 1818 Circular Country Dances (to name but a few). Novelty wasn't newly invented in the 19th Century of course, it seems likely to me that social dancers in all periods of history enjoyed novelty, this paper has offered some glimpses into what might have been encountered in the second half of the 18th Century.

We'll leave the investigation there; if you have anything further to share then do please Contact Us as we'd love to know more.

|

Figure 1. William Hogarth's c.1745 The Country Dance, part of an unfinished series about a happy marriage.

Figure 1. William Hogarth's c.1745 The Country Dance, part of an unfinished series about a happy marriage.

Figure 2. A Concise & Easy Method of Learning the Figuring Part of Country Dances by Nicholas Dukes, 1752 (left) and Country Dancing Made Plain and Easy by A.D., 1764 (right).

Figure 2. A Concise & Easy Method of Learning the Figuring Part of Country Dances by Nicholas Dukes, 1752 (left) and Country Dancing Made Plain and Easy by A.D., 1764 (right).

Figure 3. New Christmas Eve from A.D.'s 1764 Country Dancing Made Plain and Easy.

Figure 3. New Christmas Eve from A.D.'s 1764 Country Dancing Made Plain and Easy.

Figure 4. Roger of Coverly from Thompson's c.1764 Compleat Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances, Vol 2

Figure 4. Roger of Coverly from Thompson's c.1764 Compleat Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances, Vol 2

Figure 5. Maccaroni by F.P. in The Lady's Magazine, Vol III for the Year 1772.

Figure 5. Maccaroni by F.P. in The Lady's Magazine, Vol III for the Year 1772.