| Return to Index |

|

Paper 54 The Perthshire Hunt Balls of 1809 and 1810Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 23rd December 2021, Last Changed - 6th February 2022]

Sporting pursuits were an important element of British social life in the early 19th century. Towns across the country hosted  Figure 1. Ascot Heath Races c.1755-1765, courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust.

Figure 1. Ascot Heath Races c.1755-1765, courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust.

The tunes and dances that we'll encounter and consider further in this paper are:

Going to the Races

The human desire for competition must be as old as civilisation itself. The concept of a

The Jockey Club is understood to have been founded around the year 1750 in London, it would go on to become the body responsible for organising and regulating horse racing in Britain. It began life as a Gentlemen's Club that sponsored racing, the first race known to have been sponsored by them was reported on in The Sporting Kalendar for 1753. Earlier references to the club do exist however (or perhaps to different clubs with the same name), e.g. Ipswich Journal for the 2nd August 1729 and the Newcastle Courant for the 27th January 1733. The club's founding date may be unclear but it would eventually go on to regulate England's entire horse racing industry. The process by which the club achieved supremacy isn't obvious, it may (at least initially) have been invited to independently resolve disputes. For example, an incident at the Leeds Races was recorded in 1762 (Newcastle Courant, 12th June 1762) at which a rider fell from his horse and another Jockey remounted that same horse  Figure 2. Rowlandson's 1811 A Two O Clock Ordinary, image courtesy of The Tate.

Figure 2. Rowlandson's 1811 A Two O Clock Ordinary, image courtesy of The Tate.

Two social activities strongly associated with any British race week were the It went on to suggest thatAfter the sports of the day are over...the stewards have now other duties to fulfil. The usual custom is, that they should preside alternately at the table of the Ordinary....It is better, when the meeting lasts long enough, to have the balls and ordinaries on alternate days, for an ordinary should be well kept up, and that to a pretty late hour, and though it is a good old proverb...frigit Venus sine Baccho,still it must be admitted that after such asitas takes place in a merry and congenial party of the kind to which we have alluded, the partakers of it are sometimes more fit for their beds than for female society in a ball room. An ordinary does not need to be select. Any man should be received who pays his ticket, and knows how to behave himself. In some places, ladies are admitted to the ordinaries, and no one can deny that where it is practicable it adds much to the zest of the party. But it can only be done where the neighbourhood is good, parties well known to each other, and station in life so well understood that improper persons cannot think of intruding themselves.The price of tickets should not be too high; and generally speaking, an innkeeper knows that it is his interest that they should not be so. A guinea should cover every expense of dinner, wine, and waiting, especially if venison, game, fruit, &c. are supplied by the neighbouring gentry, as is in most instances the case. loyal and sportingtoasts be made at the Ordinary and that subscriptions be received for the following year. Many race weeks would feature additional entertainments including cock-fighting, boxing, hunting, hack races (involving common hack horsesthat would normally pull hackney carriages) and theatricals; some towns would hold more than one such meeting a year or extend the activities over a fortnight. The experience could be diverse, the concept has even lived on into the modern era with many annual race meetings still tracking their origins back to the 18th Century.

Figure 3. A Horse Race, date unknown. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 3. A Horse Race, date unknown. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

The Perthshire HuntThe balls we'll be studying in this paper were both held by the Perthshire Hunt in Scotland. They have been selected not because the Perthshire races were unusual or special in any way, rather there is surviving text that briefly describe these events and we lack similar information for other race week balls. The Perthshire balls are likely to be representative of what might have been expected elsewhere around the nation. The 1836 Traditions of Perth by George Penny shared the following about the origins of the Perthshire Hunt: Horse racing and archery were formerly much practiced in this quarter. It is a well authenticated fact, that the affair of 1745 was concocted at Perth races, which, prior to that period, were attended by noblemen from all parts of the kingdom. The disastrous events of that year put a stop to these amusements, and scattered the Scottish gentry to different parts of the continent; the effects of which were felt for 30 years. About 1784, the exiled families began to return, and many of the forfeited estates being restored, a new impulse was given to the county. Many of the gentlemen formed themselves into a body, styled the Perthshire Hunt; and a pack of fox hounds was procured, and placed under the management of an experienced huntsman. Their meetings were held in October, and continued for a week, with balls and ordinaries every day. When the Caledonian Hunt held their meetings here, the assemblies continued for a fortnight. The present excellent race course was formed after the enlargement of the North Inch, and for a time the Perth Turf was among the best frequented in Scotland. Although races have continued to be held pretty regularly, they have lately greatly declined in point of attraction; seldom extending beyond two days, where they formerly occupied a week.

It alleges that the Perth Races were used as a front for the planning of the 1745 Jacobite rebellion. In the aftermath of the 1746 Battle of Culloden the club ceased meeting, it was reformed around 1784. The Caledonian Mercury newspaper for the 30th October 1786 reported of the reformed club:  Figure 4. A Horse Race at Newmarket in 1799, image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 4. A Horse Race at Newmarket in 1799, image courtesy of the British Museum.

The Observer newspaper in London reported in 1807 of an unfortunate accident:

The balls were evidently of some importance to the race week festivities. The Perthshire Courier in 1811 (10th October 1811, once again with dance references in Bold) offered the following fascinating detail concerning the race week balls:

The Perthshire Hunt race weeks of 1809 and 1810

Figure 5. An Extensive View of the Oxford Races c.1820 by Charles Turner. Image courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art.

Figure 5. An Extensive View of the Oxford Races c.1820 by Charles Turner. Image courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art.

The Perthshire Hunt met here on Wednesday last. It was attended by a very great assemblage of the Nobility and Gentry of this and other counties; among whom were the Duke and Duchess of Athol, the Earl and Countess of Mansfield, Lord and Lady Gray, Lord Ruthven, Sir Alexander and Lady Mackenzie of Delvin, the Miss Mackenzies, Sir George Clark, Sir George Abercromby, the Hon. P. Drummond Burrel, the Hon. Archibald Macdonald, the Hon. Mr Douglases, General Murray, Col. Murray Stirling, &c. &c. &c. The usual entertainments of Public Breakfasts, Dinners, and Assemblies took place. There was also some racing on Thursday, which afforded little sport. But on Friday, the race, by five Gentlemen, riding their own horses, for a purse of fifty guineas, gave considerable entertainment. It was won by Captain Boyd's grey horse, Dick. The Hunt, according to their benevolent custom, left a donation to the poor. Once again we read that John Bowie led the band for this event. The following year the Perthshire Courier for the 8th of October 1810 wrote of the event (once again with dance references highlighted): The uncommon fineness of the weather was extremely favourable to the late meeting of company at the Hunt, who notwithstanding, were chiefly occupied with indoor amusements. There were some hack races on Thursday, and on Friday the whole company went to breakfast with Lord Kinnoull, at Dupplin Castle. On both days after the public dinners, most of the gentlemen and many of the ladies visited the Theatre, from which they proceeded to the dancing rooms. It appears that the Courier cared more for the dancing than the racing, we're barely informed of the sporting at all. We instead read of the people who attended the races and the tunes that they danced to in the evenings. Some thirteen or so unique dancing tunes are named across the two events, most of which we have written about in previous papers. We'll go on to consider those tunes we've not already studied shortly. The tunes and dances from the 1809 and 1810 seasons that we have already investigated are: Miss Johnston's Reel, The Cameronian Rant, Fight about the Fireside, Lady Mary Ramsay's Strathspey, Morgiana, The Prime of Life, Scotch Medley, Athole House, La Waltz and Mrs McLeod of Rasay's Reel (you might like to follow the links to read more). Each one of these tunes was genuinely popular around the entire nation at around these dates, the same play-list could easily have featured at a Ball in London without being out of place. Two band leaders have also been named, John Bowie and Nathaniel Gow. We're written of Nathaniel Gow (1763-1831) before, he was one of the most celebrated musicians of his generation. The Gow brothers in London and Edinburgh, between them, had significant influence over Britain's entire social dancing industry. Their country dancing bands were the most prestigious performers of their generation, they routinely played for the balls of the aristocracy and even those of the royal family. Let's now spend a moment investigating the life and career of Nathaniel Gow's friend John Bowie.

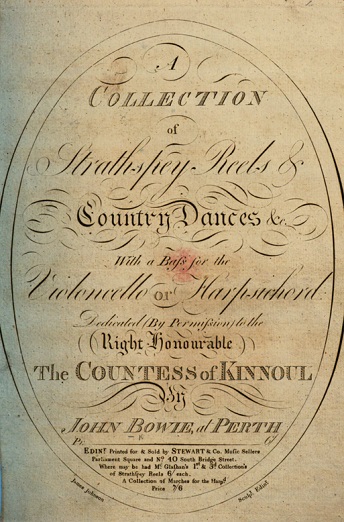

John Bowie (1759-1815)We don't know a great deal about John Bowie. He was born, according to his gravestone at the small village of Tibbermore near Perth, in the year 1759. John (1759-1815) and his brother Peter (1763-1846) both played with the celebrated band of Niel Gow (the father of Nathaniel Gow). The talents of the Gow Band were appreciated in London as well as in Edinburgh, by the 1800s the Gow band was considered to be the best Country Dancing band in the entire nation.  Figure 6. A Collection of Strathspey Reels & Country Dances by John Bowie, c.1789

Figure 6. A Collection of Strathspey Reels & Country Dances by John Bowie, c.1789

Bowie was not just a musician, he was also a composer of dancing tunes. He published his Collection of Strathspey Reels & Country Dances around the year 1789 (see figure 6). This collection of dance tunes was particularly noteworthy as it included suggested dance figures for a few of the tunes, this was the normal practice for tune collections issued in London but was almost unheard of in Edinburgh at the time. Perhaps Bowie saw value in arranging dance figures after the London fashion, he may perhaps have hoped to sell his books into the London market.

One (or perhaps both) of the Bowie brothers also formed the partnership of Bowie & Hill to sell printed music in Perth somewhere around the end of the 18th Century. One of their broadsheet publications was simply named Four New Tunes, it included a copy of Lady Caroline Lee's Waltz that was described as being Niel Gow died in 1807 shortly before the dates of our Perthshire Hunt Balls. It's possible that Niel would have led the band for the Perthshire Hunt Balls in the preceding years, Bowie and Nathaniel Gow may have inherited the responsibility from Niel. The Perthshire Courier (15th February 1816) published the following poem in tribute to Bowie after he in turn died: Ah, Bowie! so lately the life of the Ball, Bowie had evidently been a cherished part of the social life of Perth. John Bowie was survived by his younger brother Peter. When Peter in turn died in 1846 the Perthshire Courier (as quoted in the Glasgow Herald for the 16th March 1846) wrote: Death of one of Niel Gow's Band - Mr Peter Bowie, the only surviving member, with one exception, of Niel Gow's celebratedreel band,died here, on the 1st inst., at he advanced age of 83. The survivor is old Peter Murray, of Inver, now also an octogenarian, and who, with his namesake now deceased, have long outlived all the rest of that corps, without whose exhilarating strains no joyous meeting, from the fashionable assembly to the humblepenny wedding,could be said to be rightly constituted. It has been often a subject of regret that none of this famous coterie had the turn to leave on record any of the multifarious adventures which befell them in the exercise of their calling, which, from want of the facilities for travelling at the time, necessarily partook much of the characteristics of the gaberlunzie. After breaking up of the band, upon the death of its head, John and Peter Bowie, brothers, took up a shop in Perth as music sellers and teachers of the violin and piano forte, and from their talents, as well as their former popular connexion, enjoyed a large share of public support. The elder brother deceased upwards of thirty years ago, unmarried, and the survivor, being a man of frugal habits, and continuing in the exercise of his profession till lately, amassed a considerable fortune, the greater part of which we understand, he has bequeathed to the charities of this place. That eulogy was syndicated in newspapers across the whole of Britain. John Bowie was evidently loved by the people of Perth, his loss remained lamented several decades later.

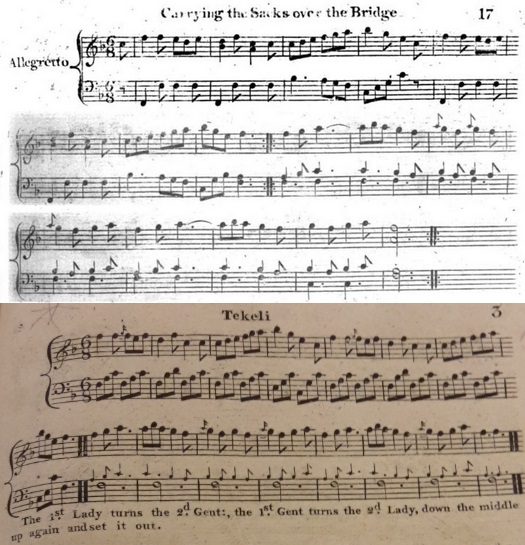

Tekeli Figure 7. Carrying the Sacks over the Bridge from James Hook's 1806 score to Tekeli (above) and Tekeli from Skillern & Challoner's c.1807 4th Number (below).

Figure 7. Carrying the Sacks over the Bridge from James Hook's 1806 score to Tekeli (above) and Tekeli from Skillern & Challoner's c.1807 4th Number (below).

The following were the leading tunes danced: ... Tekeli ...(1809 Perthshire Hunt Balls)

The first tune we'll study was danced at the 1809 race week balls, it is named

The Hampshire Chronicle for the 1st of December 1806 included a summary of the plot and the following review:

Several melodies from the production were adapted into popular Country Dancing tunes and enjoyed in 1807 and 1808. Two in particular were readily available from London's music shops. One of the tunes was named

The tune was also being danced to socially. The Morning Post for the 22nd June 1807 reported of a Ball held by The Countess of Camden at which We've animated suggested arrangements of Skillern & Challoner's c.1807 version (see Figure 7), of Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1807 version and of Button & Whitaker's c.1807 version. For futher references to the tune, see also: Tekely at The Traditional Tune Archive.

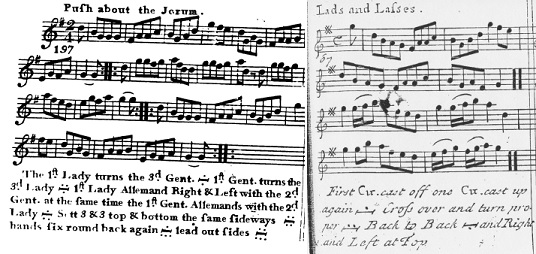

Push about the JorumThe following were the leading tunes danced: ... Push about the Jorum ...(1809 Perthshire Hunt Balls) The next tune to consider from the 1809 Balls is Push about the Jorum. The earliest publication of the tune that I can confirm was in the 1750 5th volume of Johnson's A Choice Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances where it appeared under the name Lads and Lasses (see Figure 8, right). A highly similar tune would resurface in the 1770s in a under the new and better known name of Push about the Jorum.  Figure 8. Push about the Jorum from the c.1780 fourth volume of Thompson's Compleat Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances (left), and Lads and Lasses from the 1750 5th volume of Johnson's A Choice Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances (right).

Figure 8. Push about the Jorum from the c.1780 fourth volume of Thompson's Compleat Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances (left), and Lads and Lasses from the 1750 5th volume of Johnson's A Choice Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances (right).

The new name originated in a song. Miss Catley sang a bawdy song to the modified tune of Lads and Lasses named The tune was also used for Country Dancing in London from around the year 1780. Arrangements can be found in the c.1780 fourth volume of Thompson's Compleat Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances (see Figure 8, left) and in Longman & Broderip's c.1781 200 Favorite Country Dances, Cotillons and Allemands. It can also be found in similar collections issued by Thomas Skillern and Bride at around the same date. It would also be published in Glasgow in the 1782 first volume of Aird's Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs. Thereafter the tune would seemingly disappear from published collections until the early 19th Century when it appeared in William Campbell's c.1803 18th Book and also in the Astor collection of Country Dances for 1804. It would also appear in Newcastle based Abraham Mackintosh's c.1805 Collection of Strathspeys, Reels, Jigs, &c., then, tellingly, in Nathaniel Gow's 1809 A fifth Collection of Strathspeys, Reels &c.. This final publication was issued shortly before the date of the 1809 Perthshire Hunt balls, this might imply that the tune was enjoying a resurgence in Edinburgh at around our date. The inclusion of the tune at our ball is mildly unexpected, it's not often that such an old tune would resurface in this way. I have no evidence of the tune being used at any other society events. This may well have been an obscure tune in 1809, it's only by luck that a reference to it having been danced survives. Perhaps Burns having referenced the tune was sufficient to bring it back to mind. The anomaly might invite us to question whether other old and obscure tunes were also being occasionally reintroduced at fashionable events. We've animated a suggested arrangement of Campbell's c.1803 version. For futher references to the tune, see also: Push about the Jorum (1) at The Traditional Tune Archive.

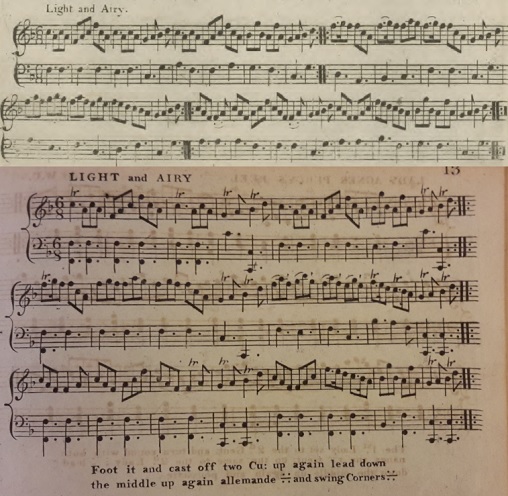

Figure 9. Light and Airy from Robert Ross's c.1780 Choice Collection of Scots Reels (above) and from William Campbell's c.1804 19th Book (below).

Figure 9. Light and Airy from Robert Ross's c.1780 Choice Collection of Scots Reels (above) and from William Campbell's c.1804 19th Book (below).

Light and AiryThe following are a few of the leading tunes which were called by the dancers; ... Light and Airy ...(1810 Perthshire Hunt Balls)

The next tune to consider was danced at the 1810 balls, it's another readily identifiable tune named Light and Airy. The phrase

Several tunes of this name have been published, the Thompson publishing dynasty issued two such tunes in their collections of Country Dances for the years 1766 and 1770. The tune from our ball was neither of these however, it was instead a tune that was republished over about 25 years from around the year 1780. The first publication I can identify of our tune was issued in Edinburgh by Robert Ross in his c.1780 Choice Collection of Scots Reels (see Figure 1, above), it would then reappear in Niel Gow's c.1788 Second Collection of Strathspey Reels &c.. It would next appear in London in Longman & Broderip's 1794 Fourth Selection of the most favorite Country Dances, Reels &c. and also in Thomas Budd's Twenty-fourth Book, For the Year 1794. Back in Edinburgh it would appear in Robert Petrie's c.1796 Second Collection of Strathspey Reels &c (under the name

The tune is also known to have been danced socially at a few other events. It was the opening dance of Mrs Knox's Rout in 1802 (Morning Post, 19th March 1802) and also at The Mansion-House Ball in 1809 (Morning Post, 5th April 1809). It was reported of the 1809 event that: We've animated suggested arrangements of Budd's 1794 version and of Dale's c.1805 version. We've also animated a suggested arrangement of Martin Platts's 1798 version of Bucks of Westmeath. For futher references to the tune, see also: Light and Airy (1) at The Traditional Tune Archive.

La TerzaThe following are a few of the leading tunes which were called by the dancers; ... La Zerza ...(1810 Perthshire Hunt Balls)

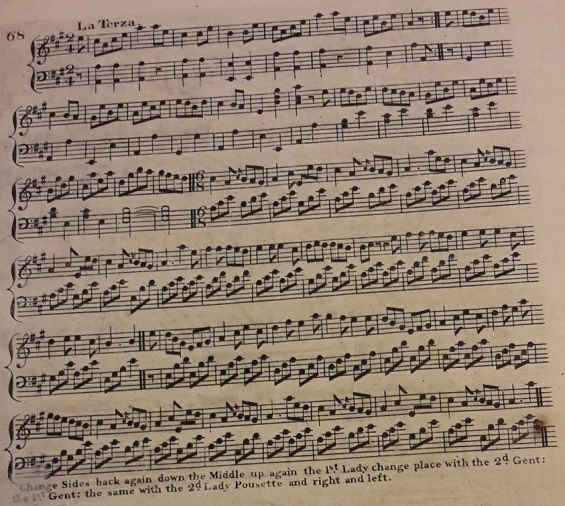

The final tune we'll investigate in this paper was named as  Figure 10. La Terza from Dale's c.1810 17th Number.

Figure 10. La Terza from Dale's c.1810 17th Number.

The first reference I know of to our tune was unexpectedly detailed. A report of Lady Johnstone's Ball in the Morning Post newspaper for the 3rd of July 1809 recorded: The tune was widely published in 1810. The precise sequence of publication is unknowable but examples include: Dale's c.1810 17th Number (see Figure 10), Goulding's c.1810 18th Number, Walker's c.1810 24th Number, James Platts's c.1810 16th Number, Skillern & Challoner's c.1810 10th Number, William Campbell's c.1810 25th Book and it was also named in Thomas Wilson's Treasures of Terpsichore for 1810. It would also appear in Button & Whitaker's c.1811 16th Number, Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1811 5th Book and in Monzani's c.1811 18th Number. Nathaniel Gow published the tune in Edinburgh in his The Favorite Dances of 1810, Edward Payne mentioned it in his 1814 New Companion to the Ballroom and Hime & Son published it in Dublin in their c.1815 22nd Number.

The tune itself is unusual for being composed half in common time and half in waltz time, it's unlike most other tunes of the period. Nathaniel Gow actually split the tune into two parts and described it as being a

Some versions of La Terza are arranged in five parts, others in four parts. The Dale arrangement in Figure 10 is in four parts, we've previously commented on Skillern & Challoner's version in five parts elsewhere. The five part arrangements repeat the

Conclusion

We don't have a great deal of information about the dancing at the Perthshire Hunt Balls, what we do have is tantalising however. We know that the band leaders were amongst some of the most capable in the entire nation and that the tunes danced were a combination of fashionable melodies of both Scottish and English derivation. We know of the 1813 Caledonian Hunt ball (which was also held in Perth) that If you would like to recreate a historical race week ball, or indeed any Ball dated to around 1810, the tunes and dances we've explored in this paper would be an elegant accompaniment to your event. We'll leave the investigation here, if you have anything further to share then do please Contact Us as we'd love to know more.

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved