|

Paper 55

Mrs Walker's Masquerades, 1800-1804

Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor

[Published - 21st February 2022, Last Changed - 2nd September 2024]

Mrs Alethea Walker (1769-1805) was, towards the end of her life, a celebrated society hostess. Her Masked Balls and Masquerades were attended by both Royalty and the Nobility, they were so popular that the Masquerade party saw a return to fashionable popularity in early 19th century London. She was the daughter of one Liverpudlian merchant and the wife of another, with an immense fortune available to spend. She was colloquially referred to as Mrs Walker of Masquerade celebrity (and with other similar epithets) in the newspapers, her fame having been secured. The events that she hosted were celebrated like no others in the opening years of the 19th century. In this paper we'll investigate what is known of her life and masquerades, we'll also pass comment on the murky sources of some of her wealth. We've previously studied the life and balls of another northern hostess, Mrs Beaumont (1762-1831), in two separate papers; both Mrs Walker and Mrs Beaumont were wealthy heiresses who hosted the London elite at their immensely popular events, you might like to follow the links to read more.

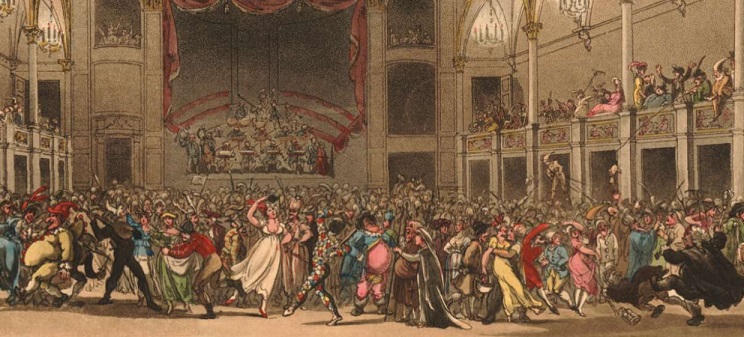

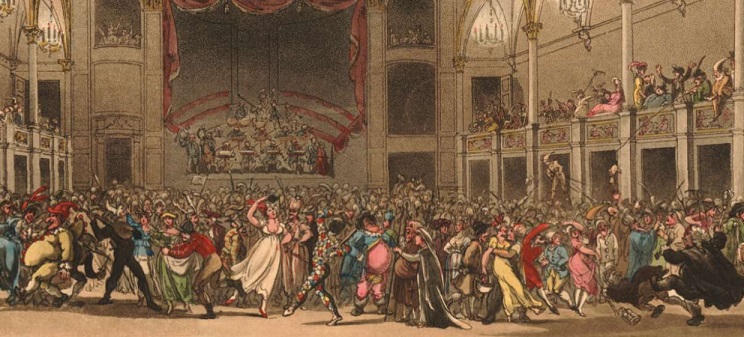

Figure 1. Pantheon Masquerade, 1809, image courtesy of the British Museum.

We'll also investigate a single tune that was named as having been danced at one of the Walker events:

Mrs Alethea Walker (1769-1805)

Mrs Walker (see Figure 2) was born Alethea James, she was the daughter of William James (1735-1798), a successful Liverpool based merchant. Liverpool is a maritime city in the north of England, its early 19th century traders profited from the sugar, tobacco, cotton and slave trades (amongst others). There were times in the 19th century when Liverpool was so successful that it is said to have contributed more to the national exchequer than London itself did. She married Richard Walker (1760-1801) in 1790, another Liverpudlian merchant, they had two sons together. Mrs Walker became a person of interest to the London newspapers from around the year 1800 when her society balls became the talk of the town, we'll read more of them shortly.

Ordinarily I might struggle to share any more of her biography at this point as she was not especially famous, the surname Walker is hardly unique. She was not a member of the old-money aristocratic clique. I'm therefore indebted to the Legacies of British Slave-ownership project at the University College London for much of what follows (we quote the project several times below). It will come as no surprise at this point to learn that the men-folk in Alethea's life had direct links to the international slave trade. Her father William James was the owner of Jamaican plantations, he employed slaves to produce his valuable sugar crops. He had died in 1798 and left most of his wealth to his son and grandson, Alethea only inherited £1000 (which was a considerable sum). His son-in-law Richard Walker was asked to accept responsibility for managing the Jamaican estates.

Addenda: A reader, Angus Graham of Liverpool, has written to share additional information about William James, Alethea's father. To mark the birth of his daughter, William James named a vessel the Alethea. This ship made four slaving voyages between 1773 and 1777 when she was a child. These were (from the Transatlantic Slavery Database) voyages #91726, 91727, 91728, 24781. There are 144 entries in the database giving William James as owner or part owner. Alethea was very much born into the slave trade. I am further grateful to Angus for making me aware of the picture of Mrs Walker in Figure 2.

The Bury and Norwich Post newspaper commented on Alethea's fortune on the 10th of June 1801, it reported that Mrs Walker, the lady who makes such a distinguished figure in fashionable life, is the wife of a Liverpool merchant, and said to be allowed 10,000l per ann. by her husband. . Whether she actually had £10000 per year to spend is unknown, it's a sum that matches the fictional income of Mr Darcy from Austen's Pride and Prejudice, she was clearly wealthy and could afford to entertain in style.

Alethea was Richard Walker's second wife. Richard was a respected member of the mercantile community in Liverpool, he inherited responsibility for his Uncle's business in 1796, as well as his father-in-law's business in 1798. The Legacies of British Slave-ownership project reports that he imported large quantities of sugar and rum and increasing quantities of coffee and logwood. In the three years 1797 to 1799, the firm imported an average of 3100 hogsheads of sugar, 900 puncheons of rum and 85 tons of logwood a year, quantities comparable to the earlier years of the decade. In January 1800 he was offering between 100 and 200 hogsheads of Jamaican sugar for sale by auction and in May of the same year he had 522 bags of Carthagena cotton for sale at his warehouse in Hanover Street. . Richard was also a slave-trader: In 1800, in conjunction with his cousin Richard Watt junior and Caleb Fletcher, he sent the Kenyon on two voyages to Bonny transporting 380 Africans to Montego Bay, Jamaica, and later 279 Africans to Martinique. He was to die before the vessel was shipwrecked on her way back to Liverpool in early 1802. . Richard had first married Martha Wilson in 1788, she was also the daughter of a slave trader, they had a daughter Elizabeth Watt Walker (1789-1804) together, Martha died shortly afterwards. Richard was remarried to Alethea the following year, their two sons were born in 1792 and 1795. He seems to have had interests outside commerce, however, and was an officer and trustee of the Liverpool Infirmary, a governor of the Dispensary and Deputy Lieutenant of Lancashire in 1798. He also lived in some style. One of his obituaries commented, Mr Walker's style of living was equal, in splendor, to that of many noblemen, and exceeded by very few. He was particularly interested in horticulture and was the first President of the Liverpool Botanic Garden. . Richard died in 1801. He had also taken up horse racing and a month after his death, there was a sale of some 10 thoroughbred horses, many with very distinguished pedigrees. His activities and interests extended outside Liverpool too, and he maintained a house in Stanhope Street in Mayfair, London. According to the diarist Hester Thrale, later Mrs Piozzi, his second wife Alethea was a noted society hostess and the fashionable landscape gardener Humphry Repton recalled how he fitted up their London house with flowery garlands and coloured lamps for a masquerade attended by the Prince of Wales. . After Richard's death the Lancaster Gazette (24th of October 1801) printed his brief obituary: On Thursday se'nnight at his seat, at Oak-hill, near Liverpool, universally and deeply regretted, Richard Walker, Esq. who is believed to have united, in as great a degree as any man of this age, the eminent merchant and the accomplished gentleman; distinguished alike in the commercial world, and the world of fashion. .

Mrs Walker hosted major society events in London in both 1800 and 1801, she then disappeared from public view for a couple of years following her husband's death. She would host another grand Ball in 1804, unfortunately her step daughter Elizabeth died later that same year. She was expected to reopen her home as a society hostess once again in May 1805 (Morning Post, 10th of April 1805), she too would die shortly thereafter (London Courier, 14th of June 1805). It seems almost as though her Masquerades were unlucky!

Figure 2. Mrs Walker and her children. Image courtesy of Sotheby's.

The newspapers didn't report her obituary in any detail, they merely wrote that she was the relict of Richard Walker, Esq. and that she had died at her George Street address in Hanover Square. The next year, however, the Morning Post newspaper wistfully recalled her when describing a Masquerade hosted by the Countess of Barrymore (24th of June 1805): The preparations were decidedly superior to any thing of the kind we have witnessed since the days of Mrs Walker, and the tout ensemble much resembled the masquerade given by that Lady in Stanhope-street, May Fair, in the year 1801 . She was still remembered in 1810 when the Morning Post mentioned a ball held by the Persian Ambassador (16th of March, 1810): Since the days of Mrs Walker's fetes we have not heard of such numbers of persons assembling together from curiosity alone . She was even remembered as late as 1813 when the Morning Post reported on Mrs Boehm's Masquerade (23rd of June 1813): The taste and spirit, the splendour and liberality, with which this Lady has given masqued fetes, reminds us of the days of Mrs Walker, who refused an established opinion that the masquerades were not congenial to the taste of the English nation. The charge is now become a libel on the national character. . Mrs Walker evidently made an impact!

Slavery and the British Ballroom

As a historical dance researcher I'd prefer not to have to think about the slave trade, it's a subject into which I have no special insight and one that is difficult to contemplate. The truth is that the entirety of the British nation benefited from the slave economy, either directly or indirectly, those legacies are still felt to this day. Mrs Walker benefited more directly than most but the guests she entertained were no less the beneficiaries of the British system than she herself was. Britain had grown wealthy from the profits of Empire: slavery, asymmetric trading, indentured servitude, plundering of resources... all on an industrialised scale. That wealth filtered through the economy, the British had sufficient disposable income to fund the production of daily newspapers as well as music and dance publications; talented individuals had the time to invent, discover and to write; the industrial revolution, vanity publishing, subscription balls, all were to some extent made possible from the profits of Empire. It therefore makes sense to consider Britain's history of Slavery a little further at this point.

Slavery itself is as old as recorded history, most historical civilisations have relied on slave labour. The 18th century saw this civilised behaviour escalated on an industrial scale as African people were transported en masse to the West Indies, most would experience a life of forced labour on the plantations owned by rich Europeans and Americans. Even referring to the victims as slaves is dehumanising: they were unique individuals with their own lives, family, goals, talents and occupations. The enormity of what happened is difficult to comprehend. The English city of Liverpool, perhaps more so than any other single place, was at the centre of the transportation industry.

Figure 3. Execrable human traffic, or the affectionate slaves, 1790. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

The editors of the modern SlaveVoyages.org database of 36000 slave trading voyages wrote at TheConversation.com that: Between 1696 and 1807 - when Britain abolished its slave trade - Liverpool merchants forcibly transported a phenomenal 1.3 million enslaved Africans across the Atlantic. Of these men, women, and children, 180,000 perished on the deadly Middle Passage - the crossing from Africa to the Americas. ... Focusing on the 5,000 Liverpool voyages shows how that town helped drive the slave trade's phenomenal growth. The first slave ship left Liverpool in 1696, but the business exploded only after 1740, when the town's merchants aggressively searched the African coast for new slaving markets. The number of slave ships leaving Liverpool climbed annually from 1696, interrupted only by periodic wars. By the end of the 18th century, Liverpool accounted for 46% of the entire transatlantic slave trade. ... The money that flowed back into Liverpool from the sale of 1.1 million men, women and children helped to transform the town into a booming metropolis by the end of the 18th century. .

The profits of slavery were immense, one estimate places it as high as 80% of Britain's foreign income in 1783 (a figure I've sourced from Wikipedia). The great surprise is not that Britain, along with many other European nations, was profiting from the slave trade; rather, that Britain had a strong and ultimately effective abolitionist movement which sought to end the institution of slavery. It took many decades to do so and the legacy would never be undone, but abolition was ultimately achieved.

The institution of slavery is one which effectively ended within the home nations of the British Isles under common law in 1772. Lord Mansfield's legal decision involving the case of a runaway slave (known as Somersett's case ) described slavery as odious and unsupportable under law. It effectively became illegal thereafter to keep slaves within the British Isles. The institution remained in force in the colonies however, British merchants continued to gain wealth from the international trade, they merely kept their slaves away from Britain's domestic shores. Slaves, for the purposes of international shipping and insurance, were considered to be little more than livestock.

Public opinion slowly changed in Britain. One of the first groups to actively seek an end to slavery was The Society of Friends, that is the Quakers movement; nine of the twelve founding members of the 1787 Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade were practising Quakers. To their voices were added those of William Wilberforce MP (1759-1833), John Wesley (1703-1891) (founder of the Methodist religious movement) and many others. Campaigners including Olaudah Equiano (c.1745-1797) helped to shape popular opinion with their first hand experiences. The Society experienced some successes; they encouraged sugar boycotts in the 1790s, women in particular were encouraged not to buy goods produced by slave labour. It is estimated that 300000 Britons may have participated in the boycotts. Abolitionist petitions were regularly delivered to parliament, this enabled Wilberforce and others to argue in parliament from a position of strength. They had to overcome the vested interests of the political classes in making their arguments however. A Foreign Slave Trade Abolition Bill in 1806 effectively ended much of the overseas British slave trade, it prevented British merchants from transporting slaves to foreign territories; it had been passed into law as an anti-Napoleonic measure (to weaken French trading interests in the Caribbean), the Bill had the hidden side-effect of preventing much of the existing British slave trade. This, once passed, cleared the path in parliament for a more complete abolition of legalised human trafficking. Wilberforce eventually saw his Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade pass in 1807. This act made it illegal for British merchants to trade slaves, the institution itself remained legal in the British colonies however. The slave trade didn't immediately end, Wikipedia reports that The Royal Navy, which then controlled the world's seas, established the West Africa Squadron in 1808 to patrol the coast of West Africa, and between 1808 and 1860 they seized approximately 1,600 slave ships and freed 150,000 Africans who were aboard. . The 1807 act was followed up in 1811 with the Slave Trade Felony Act which made slave trading a criminal offence, slave ownership however remained legal. British led diplomacy would encourage the continental European powers to also denounce slavery, the 1815 treaty signed at the Congress of Vienna by eight leading powers condemned the slave trade as repugnant to the principles of humanity and universal morality , the signatories committed themselves to begin the process of a general abolition. Back in Britain, the Anti-Slavery Society was formed in 1823 to progress the abolitionist cause, first-hand slave narratives such as that of Mary Prince (1788-after 1833) helped to shape public opinion. It was the aftermath of the Baptist War of 1832 (a slave revolt in Jamaica) that urgently shifted the British political stance, the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 was passed to fully eradicate the institution within British controlled domains shortly thereafter. The story doesn't end there of course and this review is necessarily short. You might like to follow the links to read more.

Before we leave this topic we must take a moment to consider the life of one further person of great interest, Ignatius Sancho (c.1729-1780) (see Figure 4). Sancho is understood to have been born a slave, he eventually found freedom and was employed by the Duke of Montague. Sancho created at least four collections of social dances in the 1760s and 1770s, they included Minuets, Country Dances and Cotillions, amongst which are several of my personal favourites. I've contributed to a book about Sancho's life and works that is available through the Early Dance Circle, it's named Dances for a Princess and was written by Sally Petchey. I've also appeared in a video about his life and work that is available through YouTube. The extent to which Sancho influenced the British ballroom of the late 18th century is unclear, that he did so in some capacity is certain. He was a staunch abolitionist and a man of genuine talent, he's well worth discovering more about.

Mrs Walker's Masquerade, 1800

We shall now return to Mrs Walker and her masquerades. It's likely that she hosted events prior to the year 1800, it's only in 1800 that they achieved sufficient public attention to be recorded in the newspapers. Several publications commented upon her 1800 event.

Some reports were brief, including the following from the Hampshire Chronicle for the 2nd of June 1800: Monday night Mrs Walker, of Stanhope street, gave a grand masked entertainment, which is said to have surpassed every thing of the kind ever given in London. Mrs Fitzherbert was of the party, as was also the Prince of Wales; and as a proof how much his Royal Highness was delighted with the entertainment, he did not retire till six o'clock in the morning: he accompanied Mrs F. during the whole of the evening. . We're informed, with the usual degree of superlatives, that a grand event had been hosted. We have the additional detail that the Prince was present with his chosen companion of Mrs Fitzherbert (1756-1837) for the whole of the night. The event was masked which may have added a veneer of legitimacy to their attendance together, if so then the masks fooled nobody. This was presumably the event at which (as we read above) landscape gardener Humphry Repton (1752-1818) fitted up the house with flowery garlands and coloured lamps .

The Staffordshire Advertiser for the 31st of May 1800 offered slightly more: About 700 persons of fashion were present on Monday night at Mrs Walker's Masquerade in Stanhope-street, London. Amongst the best supported characters were Mr Thos. Sheridan, who cut some neat capers as a morris dancer ; and Sir Robert Lawley as a savage ; he was however very tame. Lady Levison Gower was a primrose girl , simple, innocent, and delicate, as the little vernal flowers in her basket. The Marchioness of Donnegal as a Circassian slave in chains, was one of the most beautiful women present . There's no mention this time of the Prince and his companion, we instead learn that there were around 700 guests present and that the costumes included those of a romantic savage and a female slave.

The Ipswich Journal for the 31st of May 1800 wrote more: Near 700 persons of fashion were assembled at Mrs Walker's masquerade in Stanhope-street, on Monday night. About 11 o'clock the company began to assemble, and were received at the entrance by a band of musicians, dressed in the costume of the night, who played several charming airs. The masks were conducted up stairs, the balustrades of which were concealed by foliage and flowers, into a suite of apartments decorated with every ornament that the most exquisite fancy could imagine. The floors, both above and below, were all chalked in various devices, and from the cornices were suspended wreaths of flowers, interspersed with variegated lamps. The characters were most without exception, admirably well dressed, and many were supported with great ability and success. The fancy dresses of the ladies were distinguished for their elegance as well as a profusion of pearls and jewels: and when they unmasked, towards 3 in the morning, there was a display of beauty never exceeded in any assembly. Mrs Walker wore a black lace cloak over her habit, and her hair covered with an elegant netting of gold. The supper was sumptuous. The desert consisted of cherries, strawberries, and other delicious fruits. The Prince of Wales, Prince William of Gloucester, Prince of Orange, Duchess of Cumberland, and Duchess of Devonshire, were of the party. The company departed about 6 in the morning . This time we learn that many members of the Royal family were present, along with the upper echelons of the nobility, and that the property was richly decorated and that the supper was superb. We're beginning to get the impression that this event was more than the regular fare for the London season.

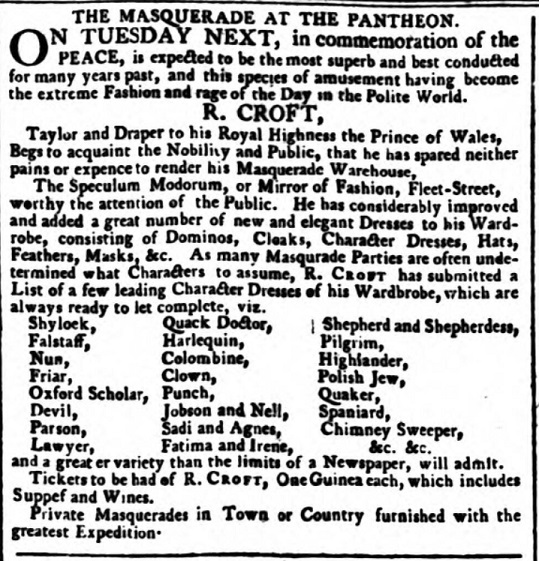

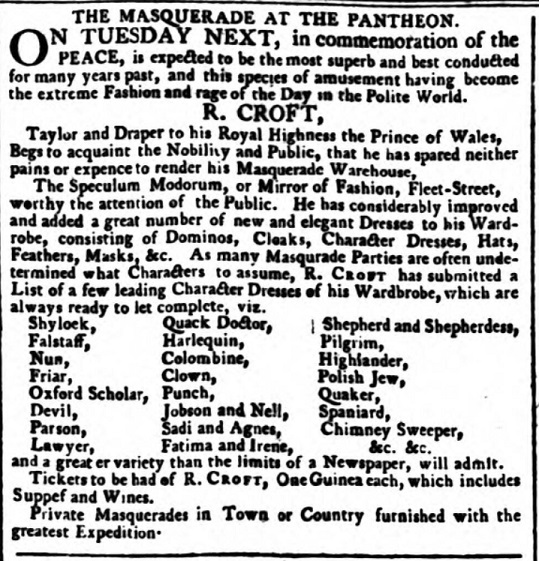

Figure 5. An advertisement for Croft's Masquerade Warehouse, the Weekly Dispatch, 25th of April 1802. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive ( www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

It is however to the pages of the Sporting Magazine that we must turn for the most complete description of the event (with dance references highlighted in bold):

The humour and naivete, with which these characters are traced out, is our principal motive for preserving an account of Mrs Walker's Masqued Ball in the Sporting Magazine. As we are by no means servile imitators of the newspapers, we have the more aversion against copying their columns, lately crowded with accounts of a Rout at Mrs Such-a-one's, Mrs What-d'ye-call-her's Gala, and Madam Thing-a-my's Ball: a practice, which giving a false consequence to many, instead of innocent mirth, may tend to promote that baneful luxury, which must end in sorrow: yet, as there is an exception in the present instance, our readers are informed, that on the evening of Monday, May 26, Mrs Walker opened her house, the corner of Stanhope-street, for the reception of masks.

About eleven o'clock the company began to assemble, and were received at the entrance by a band of musicians, dressed in the costume of the night, who played several charming airs. After a strict and necessarily minute examination of the tickets, the masks were conducted up stairs, the balustrades of which were concealed by foliage and flowers, into a suite of apartments decorated with every ornament that the most exquisite fancy could imagine. The floors, both above and below were all chalked in various devices, and from the cornices were suspended wreaths of flowers, interspersed with variegated lamps.

The characters were almost, without exception, admirably well dressed, and many were supported with great ability and success. The fancy-dresses of the ladies were distinguished for their elegance as well as a profusion of pearls and jewels, which was doubtless intended as a compliment to their amiable hostess; and when they unmasked towards three o'clock in the morning, there was a display of beauty never exceeded in any assembly.

The Prince of Wales wore a grey silk domino, with a deep lace fringed cape, and accompanied during the whole of the evening Mrs Fitzherbert, who was in a blue dress of the same kind. Mrs Walker wore a black lace cloak over her habit, and her hair covered with an elegant netting of gold. Her pleasantry and good humour easily discovered her, as well as her attentions to her company, and her inquisitiveness to discover them. Six hundred visitors attended.

The Dancing began at eleven, and was opened by Lord Milsington and the Countess of Mexborough; Mr Shirley and Lady Georgina Gordon; Lord Brook and Miss Maxwell.

The first dance was the favourite De'll among the Taylor's! and the ball concluded about five with the medley of Cameron's got his Wife again. The band, which consisted of twenty-five musical instruments, was under the able direction of Gow, and emitted the most exhilarating strains.

About four o'clock a cold collation was served in four different supper-rooms below stairs, from which the company did not retire till six. The Masqueraders exerted themselves with the happiest effect; and characteristic repartee kept the company in a flow of good-humour till the late hour of departure.

Colonel O'Kelly represented an Old Soldier as a candidate for Chelsea Hospital. His dress was quite in character, and he shouldered his crutch, and shewed how fields were won, with much effect; he also mounted guard at one of the supper-rooms, and stood sentinel till every straggler had departed.

Lady Shuldam personated a Spinning Girl , dressed with much taste and simplicity.

Lady E. Palk and the Countess of Besborough characterized Nuns , and appeared lovely enough to warm the breast of an Anchoret. Lady Palk was dressed in the robes, beads, cross &c. of the Princess Elizabeth of France.

Lady Robert Fitzgerald did great justice to the part of a Gretcian Girl .

Lord R. Fitzgerald, though a Jew , paid his respects to the ham with a very good grace.

Lady L. Manners entered into the pertness of a Fille de Chambre very happily.

Mrs Drummond Smith looked so very lovely as a Quaker , that we fear the emotions she excited were not purely spiritual .

Lord Milsington, as Jemmy Jumps, took measure of the ladies with much apparent satisfaction.

Mr Newbolt and Mr Morse, though they wished to be Clowns could not shake off the appearance of Gentlemen .

Lady Campbell, as the chaste Diana , shone with the most fascinating radiance.

Mrs Arthur Stanhope sported a character, which we believed forgot in the tonish circles, an Old Woman .

General Tarleton, as a Fisherman , angled for the Gudgeons most patiently, and met with a bite several times in the course of the evening.

Several other characters were admirably personated, though a Bond-street lounger acquitted himself rather poorly as a Sailor ; and a Watchman made so much noise with his tongue, that his rattle was useless. Mr Walker, as a HouseMaid , appeared by no means to brush off .

A Jean Debry was admirably stuffed, quilted, and puckered about the collar and sleeves, while the skirts of his coat were cut away with great economy and taste. We heard it was Mr Sk-ff-gt-n, but think it was a mistake .

The Marquis of Lorne wore a Highland dress, and Lord Holland a Spanish hat. A Bad Poet was very satirical upon one of his fraternity, whose portrait he had converted into a caricature mask, and whose verses he recited with great deal of humour. He said he was writing Odes to Boetes , and a panegyric upon the Great Bear .

We were not able to discover the owner of a large cocked-hat and two faces. This Janus gave the company no peace.

There were regiments of Jews , with their old cloaths-bags and pedlar-boxes. One might have thought one's self in Duke's-place, from their dialect and their pertinacity. Catawba-Indians , Peruvians , Virgins of the Sun , Widows of Malabar , Lucretias , and Cleopatras , were the mob of the night. The Duchess of G----n, with her daughters and Miss F-rd-e, formed a groupe of Pilgrims , but were scarcely distinguishable among the Caravans performing the same pious journey.

Mr Sheridan, jun. and another gentleman, were very happy as a couple of Country Bumpkins out of place. They offered their services to Jews, Friars, and Vestals ; and, we believe, found employment at LAST.

To conclude -- to the frequency , the publicity and effect of these private amusements, a standing objection presented in the too strong contrast, obtruded by the absolute famine among the lower orders. This is the more to be lamented since even the Quaker-made soup, though as poor and meagre as their own souls, is no longer to be had in the metropolis. -- In fine, the upper ranks seem to have changed the ancient and solid hospitality of Old England, for the frivolity and dissipation of France, which preceded the late Revolution.

Figure 6. Tom & Jerry larking at the masquerade supper, at the opera house, 1820. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

For all their aversion to copying content from the newspapers, it appears that the Magazine did so (at least in part) as some of the text precisely matches that from the Ipswich Journal. We do however learn that a 25 part band played for the evening under one of the Gow brothers, presumably John Gow, and that they danced to both Devil among the Taylors and to Cameron has got his Wife again. We've studied the first of those tunes before, we'll go on to study the other below. We also learned much more of the costumes that were worn. It's this event that raised Mrs Walker's profile so significantly; she was evidently known before the event as she persuaded much of the nobility to attend, it's this masked ball that secured her reputation as a first class hostess.

Mrs Walker didn't invent the Masquerade Ball of course, such events had been a common form of entertainment throughout the 18th Century, they would however be advertised with greater frequency after her 1800 event. One historical newspaper archive that I use currently lists 11 instances of the word masquerade in the London newspapers for the year 1799, 10 for 1800, 186 for 1801 and then 200 or more for each year thereafter for the remainder of the decade. Regular Masquerade balls would be advertised at both Ranelagh Gardens and at The Pantheon. At least four Masquerade Warehouses opened to provide costumes for such balls from around the start of the 19th Century. Figure 5 is an 1802 advert for Mr Croft's Masquerade Warehouse (in Fleet Street), including a list of the types of costume that could readily be supplied. Similar services were available from Mrs Richman's Masquerade Warehouse (Oxford Street), from Mr Bealby's Masquerade Warehouse (Coventry Street), from Mr Wayte's Masquerade Warehouse (Panton Street) and from Mr Timewell's Masquerade Warehouse (Cockspur Street) in 1801.

Mrs Walker's Ball, 1801

Mrs Walker had left London before the start of 1801, The Times newspaper for the 12th of January 1801 reported Mrs Walker, of masquerade memory, does not return to town before March next. The family are now at Liverpool. . The Morning Post newspaper for the 23rd of March 1801 echoed this sentiment by reporting that Mrs Walker, of Masquerade memory, returned to town a few days ago from Liverpool. .

Shortly thereafter she hosted a ball. The Morning Post for the 12th of May 1801 forewarned that Mrs Walker's ball, tomorrow, will be for a small party of friends only . They then published the following account on the 15th of May concerning that small gathering of friends (with dance references in bold):

The first assembly this season, was, on Wednesday evening, attended by a small party of two hundred fashionables, among whom were---

The Prince of Wales, Prince William of Gloucester, Dukes of Cumberland and Orleans, Duchesses Devonshire, Bolton and Gordon, Marquis of Lorne, Marchioness Dowager of Donegal

... [a long list of other names appeared here] ...

The Ball was opened at a quarter after eleven o'clock with Master Sitwell by The Duke of Orleans and Lady Mary Bentinck; next followed,

Mr Thomas Sheridan - Miss Manners

Captain Churchill - Miss Cornewall

Captain Pierrepoint - Lady C. Harris

Mr John Mannors - Miss Crofton

Lord Forbes - Miss Eden

Mr Fawkener - Miss Godfrey

Mr Greville - Miss Fordyce.

Thirty couple led down to the second time, Mrs Gardner a troop and at two o'clock the company adjourned to the supper rooms.

The supper had to boast of all the well known taste and elegance in which the lovely hostess excels many of her fair contemporaries. It was arranged on eight tables; three long tables were placed in the chapel for 120; at the upper end a round table for six persons; in the vestibule and parlour were placed the other four, for the rest of the company. About 200 sat down to table. The novelties of the season were cherries and strawberries.

A very superb service of new plate was made for the Prince's table -- the dishes, plates, &c. were of frosted silver, richly chased, except in the concave, where they were gilt. The Prince of Wales did not stop supper. At three o'clock the ball recommenced with Lady Mary Ramsey, and at half after five the company departed.

The Ladies dresses were more than usually rich and splendid; gold and silver muslins were much worn; ostrich feathers, tiaras, aigrette, cameo bracelets, &c. White muslins, with silver rings or circles of silver, formed into different devices, appear to be perfectly novel.

They then added in a supplement on the 23rd of May 1801 At Mrs Walker's late ball and supper pines and grapes were introduced in profusion, for the first time this season. They were uncommonly fine, and were brought from Mr Walker's pinery in Lancashire. The liberality with which the above Lady's entertainments are conducted has long been the topic of conversation in the circles of rank and fashion. .

Three tunes are specifically mentioned as having been danced at this party, we've investigated them all before: Master Sitwell, Mrs Gardner a troop and Lady Mary Ramsey. This relatively small gathering of just 200 socialites would be followed by another Masquerade Ball later in the year.

Mrs Walker's Masquerade, 1801

Mrs Walker held another Masquerade Ball at the start of June 1801. The Morning Chronicle newspaper for the 4th of June 1801 commented on how few people, in consequence, attended the scheduled Masquerade event held at Ranelagh Park: The Masquerade at Ranelagh, on Monday evening, was but thinly attended. There were no characters deserving of notice. The managers had prepared an entertainment which merited better encouragement . It seems that everyone was preparing for Mrs Walker's event instead, they continued: Mrs Walker's Masquerade on Monday evening, excelled every thing of the kind which has occurred in the fashionable world this season, in variety and well supported character. No plain Dominos were admitted. The company consisted of above 700, and the supper and wines were of the first quality . The Bury and Norwich Post (10th of June 1801) commented that From 25 to 30 guineas are said to have been given for procuring a ticket, at those shops where private invitations are bartered. The supper was voluptuous in the extreme, little according with the present loudly clamoured ideas of scarcity! . It was evidently another major event in the fashionable world.

The Morning Post for the 3rd of June 1801 printed an extensive list of the guests at the event; they listed 3 Princes, 4 Dukes, 4 Duchesses, 4 Marquisses, 5 Marchionesses, 13 Earls, 22 Countesses, 7 viscounts, 8 Viscountesses, 21 Lords, 65 Ladies, 1 Baron, 18 Sirs, 2 Generals... and so the list continued. On the 5th of June 1801 they added: The beauty of the Ladies at Mrs Walker's Masquerade is still the theme of wonder. Amongst those most remarkable for elegance of form and beauty we distinguished Ladies Conyngham, Lawley, Donegal, Throgmorton, Mrs Gardiner, and the two lovely daughters of the Marquis of Abercorn. Amongst the characters who deserved particular notice were Mr James, as a Cottager's Wife , who supported the character with much spirit, with the true provincial dialect. Mr H. Repton, in a fancy dress of white muslin, with scraps of poetry on different parts of his robe. On his head was written Folly in the cloak of wisdom . Captain Heard, a Sailor , quizzed the land-lubbers who assumed the character of British tars .

It is however to the pages of the Courier newspaper that we turn for a full description of the event, they printed an extensive account on the 3rd of June 1801 (with dance references in bold):

Figure 9. The Return from a Masquerade, 1784. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

The taste and spirit, the splendour and liberality, with which this Lady has given Masquerades, have brought them into fashion in the higher circles, and refuted an established opinion, that the amusement is not congenial to the English character. The general expectation was so much excited respecting her masquerade of Monday night, that many persons of distinction came from distant parts of the country to it; and others, who never frequent our circles of fashion (the Duke of Gordon, for instance), thronged to this scene of mirth and novelty, in Stanhope-street, May-fair. Upwards of 700 persons were present; a list of whom we shall present to-morrow, not having room for it this day. It includes the Whole circle of the fashionable world.

The entrance of Mrs. Walker's house, the inner hall, was brilliantly lighted by circles, stars and festoons of variegated lamps. The stair-case was made into an alcove by oak and laurel leaves, among which small globular lamps were placed, producing at once a light and cool effect. Under the stair-case was placed a band of music in fancy dresses.

The windows of the rooms were ornamented with boughs, in which were entwined roses and honey-suckles. Five six-light lustres were placed on the mantle-piece of the principal anti-chamber, into which the company retired from the heat of the other apartments. In a room adjacent a band of soft music played the whole night. The ball room was chalked to resemble flowers, and was lighted up with superb chandeliers and lustres. In this enchanted palace, apparently on fairy ground, the company began to assemble about eleven o'clock.

Of the taste and judgment displayed in the choice of characters, it is impossible to speak in adequate terms of praise. The whole fashionable world, it will be said, formed one immense masquerade, at Mrs. Walker's. There hundreds of performers played each a particular part; nine-tenths of our brightest belles and beaux were in disguise. No such thing. With very few exceptions, every one chuses the costume and character most conformable with the spirit, nature, and disposition of the individual. Such was the opinion of the wisest and most ancient philosophers, for what was the Metempsychosis of Pythagoras, what all his doctrine of transmigration, but a Masquerade in a state of permanence, where Misers were transformed into Ants, Dunces into Asses, and Praters into Parrots! Need we then wonder to find Miss Rose a Flower Girl , Mrs. Lushington a Witch , for who more witching? the pretty innocent Miss Irby a Primrose Girl , and Monk Lewis the Devil ? Ever since Madame D'Arblay wrote her Cecilia , his Infernal Majesty has been a standing dish at every Masquerade, but we doubt whether it wanted the benefit of precedent to recommend the present character as an example for imitation. --- The parallel and sympathy must not, however, be pursued too far. Spanish dresses, Donnas, locks and chains, are as congenial with jealous husbands as Turkish dresses impart all the sensuality of the Seraglio. Yet as extremes always run into each other, the Spanish and Turkish ladies, such as Lady Castlereagh, Viscountess Hampden, the Marchioness of Hertford, the Marchioness of Donnegal, Miss May, Mrs Rose, and Lady Charlotte Greville, were models of connubial candour, confidence, and innocence, while a Queen Elizabeth , a Quaker , a Diana Old boy , and a Pilgrim , might, as being supported by Gentlemen of fashion and frolic, prove less congenial with their assumed characters. --- Amidst this tumultuous and revolutionary variety, what eager inquiry and pursuit? Here a groupe of tars advances, there a groupe of coxcombs retires. They are the English in pursuit of the French fleet. Interrogatories are put, the shape is critically examined, the voice is disguised. Oh! how great the pleasure of deceiving! The accomplished Lord Lovaine thinks himself secure from discovery in the character of a Waggoner ; Mr. Dent, as Falstaff ; Mr. Gregg as his double in every respect, both in size and perfection. Lady Charlotte Lindsey, as a Kitchen Maid ; Mrs Champneys, as a Milkmaid ; Lady Ashburnham, as a Country Girl ; Lady Susan Hamilton, as a Dutch Housemaid ; Mr. Champneys, as Judge Ashurst ; the elegant Mr Lumley and Col. Byng, as Clowns ; Capt. Churchill, as a Rustic ; and Lord Mansfield, as a Poor Soldier . Yet all this studious concealment only led to notoriety, and the better the character was supported the more likely it was to excite curiosity, and consequent discovery.

Among those that excited the greatest interest, and were best supported, are to be reckoned the following: â the Hon. Mrs. Walpole, in the character of Goody Notable , displayed a great deal of wit and good humour; she gave a deal of good advice to the London fine Ladies, recommending notable employments, works of all kinds instead of cards and idleness. Her daughter Patty supported her character very well, was her mother's own child: both contributed much to the amusement of the company.

Mrs. Musters, an Indian Queen . -- The dress uncommonly beautiful and appropriate: the robe of Indian grass; the vest of silk; a profusion of jewels, particularly pearls, as ear-rings, necklaces, &c. the hat made of grass, the crown running up to a spire, from which issued forth a plume of Indian feathers; around the rim gilt bells.

Captain Herne, a sailor ; Mr. Janes, a farmer's wife ; Lord Villiers, a Highland chief ; Mrs. Harcourt, a Welch lady ; Mr. Boehm, a Dutch Burgomaster's wife ; the Marquis of Lorne, and Mr. T. Sheridan, as Highlanders ; and Mr. Paul Methuen, a dragon , with wings, tail, and all complete. The dragon was horribly fine, and terrific enough to pass for him that watched the golden fruit in the garden of the Hesperides; -- as such he was addressed by Lord Ashtoun, in the character of Sylvester Horticol , gardener, who presented him with the following bill

[a long and uninteresting passage omitted here]

Mr. Champheys, as Alderman and Mrs. Gobble , formed a couple of one bone and one flesh, that defied all the omnipotence of parliament to divorce till death. Indeed the Alderman, by carrying his wife on his back, appeared to guard pretty well against Crim. Con. and as a further security, the Lady had no corporal existence, unless Mr. Joddrel, who personated Nobody , lent her one. The following Song very truly describes their attachment:

[Another long and uninteresting passage removed]

It is a constitutional defect in the masquerade system, that, while the frame is all in motion, the wit sparkling, and the spirit all on fire, the mask displays no varying features - nothing but this corresponding expression of countenance was wanting to render Mr. Percy's Otaheite Chief , Mr. Williams's Schoolmaster , Mr. Smith's Sylvester Daggerwood , Miss Vaughan's Gleaner , and Lord Milsington's Quack Doctor , so many chefs d'ouvres . Indeed, in acknowledging the merits of the latter character, the epithet of appropriate in stile, spirit, and action, was only common to this, with a variety of other characters, who lashed the prevailing foibles and follies of the day with the happiest strokes of satire.

The lovely hostess of the night wore an elegant fancy dress, and looked divinely. Lady Dashwood King also appeared in one of uncommon splendour. The Prince of Wales wore a slate coloured domino, with a netting of black lace to the middle.

We cannot conclude without adding to the mass of excellence Col. Armstrong, a French Officer , loud in praise of Bonaparte; Mr. H. Greville, the Grand Signior , not throwing the handkerchief, but issuing cards for another Pick Nick . Among a long list of other characters too numerous to mention, were: Lord Courtney, an Antiquated Woman of Fashion ; Miss Brudenell, a Fortune-teller ; Earl Mount-Edgecumbe, an Old Maid , playing on the guitar; the three Mr. Haywoods, Turks ; General Tarleton, an Indian Chief , Mrs. Tarleton, one of his wives; Mr. Cox, a Patent Extinguisher ; Miss Crofton, a Female Tartar ; Lady Cahier, a Pilgrim ; Mr. S. Bouverie, a Coxcomb ; Mr Singleton, a Gypsey ; Miss Marsham, an Indian Queen ; and Mr and Mrs Drax Grosvenor, a Clown and Country Wench .

The dances commenced at one, and the Marquis of Lorn and Mr. T. Sheridan gave the Highland fling in perfection. At two the supper rooms were thrown open, the chapel constituting the chief apartment. The windows were taken out and beautiful transparent sea-pieces substituted. Five chandeliers of extraordinary beauty, and double the number of lustres affixed to the wall, threw over the chapel a refulgence not to be exceeded by the meridian sun.

The supper was cold, and Consisted of every delicacy in profusion, with the most delicate and rare wines. The Prince of Wales and Prince of Orange stopped supper, and for them and their friends a superb set of plate was set out in a private room. Though many of the company did not unmask, it was no difficulty to discover numbers of beautiful women of the most elegant form. The supper of course promoted the mirth and good humour, and it was not till six o'clock that any diminution of the guests was obvious. They all retired, delighted with a most charming night's entertainment.

Figure 10. The Prince of Wales presiding over a Masquerade ball, 1807. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

The only dance mentioned as having been exhibited was the Highland Fling. We've commented on this dance form before in previous papers, for example we've discussed the theory that it was invented (or popularised) by the dancing master George Jenkins. We're informed that it was danced by two men at the Masquerade, it may therefore have been a twasom strathspey or reel of two dance. We've written of the general confusion surrounding Scottish dance terms in English sources elsewhere. You might like to follow the links to read more.

Mrs Walker left London shortly after the Masquerade, the Morning Post for the 9th of June 1801 reported that: Mrs Walker passes part of the summer at her seat near Brighton, where the gay world will be happy to find her giving such entertainments as her Masquerade on Monday . They added on the 23rd of June that Mrs Walker, of Masquerade memory, resides at a beautiful seat about seven miles from Brighton. Mr Walker has found much benefit from the change of air. . Mr Walker did not last long however, the Bury and Norwich Post for the 28th of October 1801 reported that Mr Walker, the rich West India merchant, husband to the Lady of that name, so much celebrated for the splendour of her Masquerades, died last week at his seat near Liverpool .

Mrs Walker's Masqued Ball, 1804

Mrs Walker was absent from the newspapers for a little while until the British Press noted in 1803 (3rd of March) that Mrs Walker, of Masquerade celebrity, has taken a house in Sackville-street. . She seems to have been friends with the Countess of Derby, the British Press for the 18th of April 1803 reported that Mrs Walker, of Masquerade celebrity, returned to town yesterday from the Oakes, where she had been on a visit to the Earl and Countess of Derby. . The Morning Post for the 11th of May 1803 continued: Mrs Walker, celebrated for the splendour and taste of her masquerades, appeared for the first time, in the fashionable circles for two seasons, at the Countess of Derby's Rout, on Friday night. . It wasn't until 1804 that she next hosted a Masquerade.

Several newspapers on the 6th of July 1804 issued the following shared text, we'll quote from the The Star newspaper:

This elegant Lady, long celebrated in the fashionable world for the superior taste of her masqued fetes, opened her house in George-street, Hanover-square, for the first time since her widowhood, on Wednesday evening. The number of tickets issued did not exceed three hundred, and every necessary precaution was taken to prevent the intrusion of improper persons. From eleven until one the company continued to arrive, but feveral masks gained admission as late as two o'clock. The preparations for the occasion were in a very elegant style. A terrace, or platform, was erected at the bottom of the garden, and fitted up with oak and laurel leaves which formed an arched covering; variegated lamps were entwined, and the whole was surmounted by the British Star, composed of purple and yellow lamps. In the centre was stationed a band of Italian Musicians (similar to the Milanese Minstrels), who played there until the dawn. Next the Ottoman or breakfast room a beautiful alcove was formed by the union of several trees, lighted with variegated lamps, feathered among the branches. This bower was intended as a temporary retreat, had the heat proved oppressive: it was fitted up with sofas in the eastern taste. The other parts of the garden were ornamented with branches of oak and laurel, with festoons of lamps, and the perspective from the lower apartments of the house communicating through the medium of folding doors, had the most beautiful effect imaginable. The internal decorations of the mansion were strictly in union. The hall and staircase were ornamented with flowers and Chinese lanthorns, and the suite of apartments on the drawingroom floor were illuminated by chandeliers and lustres, which rivalled the meridian fun. Among the best supported characters were the following:

Mr. Browne was a most excellent Sir Archy McSarcasm; the Hon. William Spencer, as the Devil upon Two Sticks, took an accurate survey of the company, and reported to his friend Asmodeus his opinion respecting them. Lord Hamilton (eldest son of the Marquis of Abercorn) was admirably dressed as a Turk, and made an elegant appearance. The Spaniards were not numerous; among the most splendid were the Marquisses of Abercorn and Hartington, Earl of Besborough, Lord Claude Hamilton, Mr Parry, &c. - Among the religious characters, Mr. Bagot was a Friar, and the beautiful Mrs O'Brien a Nun. Among the devotees were the beautiful Lady Castlereagh and Lady L. Corry, as Pilgrims. -- Jews were very numerous: among the number were, Captain Armstrong, Mr. Jekyl and Mr. G. Upton; the latter as Shylock. The Earl of Lauderdale was an excellent Old Maid. Mr. H. Wrottesley and Mr. Champneys, as Sir Solomon and Lady Simons, with Messrs Armstrong and Maddocks, as two attendant Jews, were excellent. Mr C. Moore, a French Cook; Mr. G. Thellusson, a Dancing Master. One of the best dressed and supported characters was an antiquated Old Maid of the year 1700. She danced a minuet with Mr. Champneys, to the music of Mr. G. Thellisson's fiddle.

Many anxious inquiries were made to ascertain who the old lady was, but the discovery was made by the Prince of Wales, who soon recognised the original in the person of Mr. Mellish. -- The Gypsies were as numerous as usual; among them we noticed the Countesses of Clare and Cork, Lady E. Forster, Mrs. Ariana Egerton. Mr. H. Greville was at the head of the tribe.

Much laughter was excited by the whimsicalities of Mr. T. Sheridan, who arrived about one o'clock post, as the Blacksmith from Gretna Green, in search of business, and accompanied by Mr. C. Calvert, who was dressed as Hymen. Among the foreigners, Mr. Lawrence was most prominently attired in the real costume of a Laplander, and he appeared to possess all the apathy of that frozen climate. Even the numberless beauties present could not thaw his inflexible countenance into a smile. Of Flower Girls, there were only two personified by Lady H. Cavendish and Madame Gramont. The English Clowns were as numerous as usual; among the numbers were Mr. Giles and Mr. Nourse.

As beauty is seldom seen to more advantage than in a Spanish habit, so here we found the Duchess of Devonshire in black and silver; Duchess of Rutland in lilac and Silver; Marchioness of Hertford in crimson and silver; Lady Ramsden, Lady C Hamilton, Lady S. Stewart, were likewise in Spanish Dresses. Viscountess Dungannon looked beautifully in a fancy dress.

About two o'clock the company partook of refreshments, which consisted of every delicacy of the season. About three o'clock dancing commenced in the drawing room, and concluded about five, when the company departed. The Prince of Wales was dressed in green with a Star, and wore the Order of the Garter.

Among the company in dominos and fancy dresses were -- ...

A long list of names followed. We know little of the dancing at this event, though an impromptu Minuet was evidently witnessed. Once again we read far more about the costumes that were worn than about anything else. This was the final Masquerade that Mrs Walker is known to have hosted, she died roughly a year later.

We've now encountered five named tunes that were danced across Mrs Walker's events, we've investigated four of them before: The Devil among the Taylors, Master F. Sitwell's Strathspey, Mrs Garden of Troup's Strathspey and Lady Mary Ramsay's Strathspey. We'll now investigate the final tune.

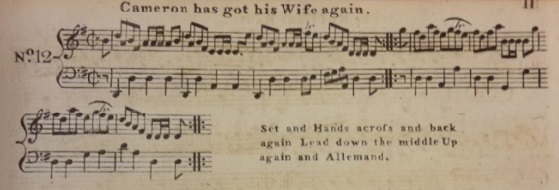

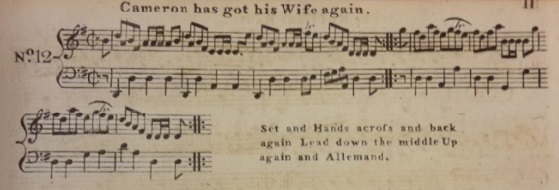

Figure 12. Cameron has got his Wife again from Martin Platts's Book 25 for the Year 1798. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.55.(1.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Cameron has got his Wife again

the ball concluded about five with the medley of Cameron's got his Wife again (Mrs Walker's Masquerade, 1800)

This particular tune had been in print since the 1750s but had seen a return to prominence in the late 1790s. The first publication that I can confirm was in Edinburgh in the 1757 first part of Robert Bremner's A Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances under the name Camron has got his Wife again . It would appear shortly thereafter in London in the c.1764 second volume of Rutherford's Compleat Collection of 200 of the most celebrated Country Dances and also in the c.1789 Caledonian Muse publication from the Thompson publishing dynasty. The eponymous Cameron would sometimes by named as Camron , Cammeron and even Cam'ron across these publications. Niel Gow included the tune in his 1792 A Third Collection of Strathspey Reels &c in Edinburgh, it was also published in Glasgow in the c.1794 4th volume of Aird's Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs. Robert Mackintosh printed it in his c.1796 3rd Book of Sixty Eight New Reels and Strathspeys. Publishing then moved back to London where it appeared in the Thompson collection of 24 Country Dances for 1797 under the new name of Miss Ester Stanhope's Reel ; at around the same date it was published under the original name in William Campbell's 12th Book. Thereafter it appeared in Martin Platts's Book 25 for the Year 1798 (see Figure 12) and in Preston's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1799 under the new name of Capmbel Has Got His Wife Again . It would also appear in Goulding's c.1803 2nd Number, in Davie's c.1802 4th Number and in Astor's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1804. It would go on to appear in Thomas Wilson's 1816 Companion to the Ballroom and in Nathaniel Gow's 1819 2nd Part of The Beauties of Niel Gow. It's likely that the title was understood to imply Cameron has got his Wife pregnant again .

The tune must have been popular to have been reprinted so many times.

We've animated a suggested arrangement of the Platts version from 1798 (see Figure 12).

For futher references to the tune, see also: Cameron has got his Wife again at The Traditional Tune Archive.

Conclusion

Mrs Walker's masquerades were conducted on a lavish scale, so much so that The Courier newspaper reported (3rd of June 1801): The taste and spirit, the splendour and liberality, with which this Lady has given Masquerades, have brought them into fashion in the higher circles, and refuted an established opinion, that the amusement is not congenial to the English character. . She was credited with personally restoring the Masquerade to fashion. Whether it was her liberal spending, the pineapples and other exotic fruits from her personal pinery, the exclusive guest list, or perhaps just her personal charm and conviviality, the mechanisms remain unclear. Her parties were sufficient to drag the most reluctant of guests into attendance, The Courier continued: many persons of distinction came from distant parts of the country to it; and others, who never frequent our circles of fashion (the Duke of Gordon, for instance), thronged to this scene of mirth and novelty . As late as 1813 the Morning Post newspaper (23rd of June 1813) wrote of the days of Mrs Walker, who refused an established opinion that the masquerades were not congenial to the taste of the English nation when referring to a recent Masquerade event. She evidently did something right.

And yet we should not forget that the source of her wealth was tainted, her fortune was (at least in part) derived from human misery. The same may have been true for many of her guests. Some slave owners and traders were applauded at home for their public displays of altruism, their wealth helped to fund charities and good causes, it was all too easy to ignore what happened in the distant realms of empire.

The modern enthusiast who recreates the balls and masquerades of the early 19th century might prefer not to dwell on the injustices of the past. In so far as the modern Regency dancing phenomenon is an escapist hobby, enjoyed by many and open to all, that's not unreasonable. The fantasy of a modern Regency Ball can ignore the awkward realities of the past: poverty, violence, inequality, gender disparities, slavery... we all dance together, role-playing as whoever we want to be. An honesty is required though, and humility too; there is a very real potential for indignation and offence when recreating (even in romantic fantasy) elements of the past.

It's at this point that we'll end this investigation. If you have anything further to share then do please Contact Us as we'd love to know more.

|

Figure 1. Pantheon Masquerade, 1809, image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 1. Pantheon Masquerade, 1809, image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 2. Mrs Walker and her children. Image courtesy of Sotheby's.

Figure 2. Mrs Walker and her children. Image courtesy of Sotheby's.

Figure 3. Execrable human traffic, or the affectionate slaves, 1790. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 3. Execrable human traffic, or the affectionate slaves, 1790. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 4. Ignatius Sancho, 1768. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 4. Ignatius Sancho, 1768. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 5. An advertisement for Croft's Masquerade Warehouse, the Weekly Dispatch, 25th of April 1802. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Figure 5. An advertisement for Croft's Masquerade Warehouse, the Weekly Dispatch, 25th of April 1802. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Figure 6. Tom & Jerry larking at the masquerade supper, at the opera house, 1820. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 6. Tom & Jerry larking at the masquerade supper, at the opera house, 1820. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 7. The Union Club Masquerade, 1802. Image courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art.

Figure 7. The Union Club Masquerade, 1802. Image courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art.

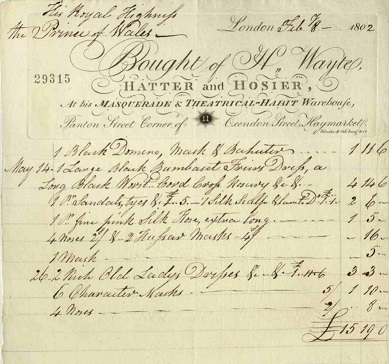

Figure 8. The Prince of Wales's masquerade costume invoice, 1802. Image courtesy of the Georgian Papers Program.

Figure 8. The Prince of Wales's masquerade costume invoice, 1802. Image courtesy of the Georgian Papers Program.

Figure 9. The Return from a Masquerade, 1784. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 9. The Return from a Masquerade, 1784. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 10. The Prince of Wales presiding over a Masquerade ball, 1807. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 10. The Prince of Wales presiding over a Masquerade ball, 1807. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

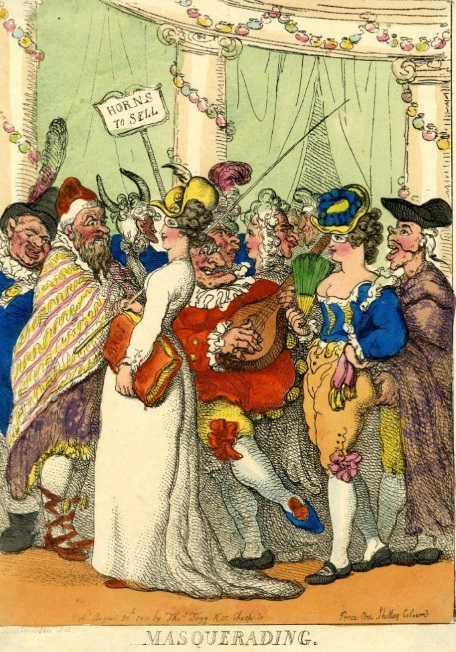

Figure 11. Masquerading, 1811. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 11. Masquerading, 1811. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 12. Cameron has got his Wife again from Martin Platts's Book 25 for the Year 1798. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.55.(1.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 12. Cameron has got his Wife again from Martin Platts's Book 25 for the Year 1798. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.55.(1.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.