|

Paper 57

S. J. Gardiner's A Definition of Minuet-Dancing , 1786

Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor

[Published - 5th May 2022, Last Changed - 14th July 2022]

Notice: Undefined offset: 3 in /hermes/bosnacweb09/bosnacweb09ak/b1453/ipw.mgnotley/public_html/712/711header.php on line 720

Notice: Undefined offset: 4 in /hermes/bosnacweb09/bosnacweb09ak/b1453/ipw.mgnotley/public_html/712/711header.php on line 720

Notice: Undefined offset: 5 in /hermes/bosnacweb09/bosnacweb09ak/b1453/ipw.mgnotley/public_html/712/711header.php on line 720

S. J. Gardiner was a Shropshire based dancing master who published a book on Minuet dancing in the 1780s (see Figure 1). This paper contains a full transcript of Gardiner's book, together with a brief commentary on the author's life and work. Gardiner's treatise offers one of the most complete descriptions of the Minuet dance of late 18th Century Britain, it will be of significant interest to anyone seeking to recreate courtly dance styles of the Georgian period. It also included extensive notes on behaviour in polite society, it evidently aimed to make a Gentleman or Lady of the reader.

We've previously shared a transcript of F.J. Lambert's 1815 Treatise on Dancing in another paper, it continues the story of the Minuet dance into the 19th century, you might like to follow the link to read more.

Index to the Book

Gardiner's A Definition of Minuet-Dancing did not contain an index or table of contents; the following index is provided as an aid to locating sections of particular interest within the work, the names of the sub-sections are as provided within the work itself.

S. J. Gardiner

Our author was named S. J. Gardiner, relatively few details of the author's life are known. Gardiner refers to themselves as a Dancing-Master on the cover of the book, from this we might assume that Gardiner was male. We'll use the pronoun he hereafter on that assumption. Gardiner claimed within the work to have been a principal dancer for several years at a theatre in Venice, he had also performed at the Court of Parma and at Florence. He also reported having worked in Paris. These claims can be found within his book in the section on Stage-Dancing. If they are believed then he must have been a talented performer and dance choreographer at an earlier stage of his career. He claimed to have taught several prominent British noblemen to dance, notably Lord Cowper (1738-1789), Lord Northampton (1737-1763) , Lord Downe (1728-1780) and Sir Brook Bridges (1733-1791). These biographical details are unverifiable but entirely plausible. He presumably retired from the stage and then took up private dance tuition.

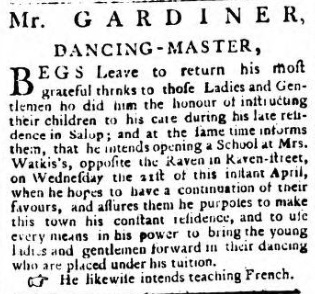

Figure 2. Mr Gardiner's advert in the Shrewsbury Chronicle, 3rd of April 1773. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive ( www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

By 1786, at the date of publication, he was resident in the town of Madeley near Shrewsbury in Shropshire. He had probably lived in the area for at least 13 years by that date, based on an advertisement for his services published in the Shrewsbury Chronicle in 1773 (3rd of April, see Figure 2); that advertisement reads: Mr Gardiner, Dancing-Master, begs leave to return his most grateful thanks to those Ladies and Gentlemen who did him the honour of instructing their children to his care during his late residence in Salop; and at the same time informs them, that he intends opening a School at Mrs. Watkis's, opposite the Raven in Raven-street, on Wednesday the 21st of this instant April, when he hopes to have a continuation of their favours, and assures them he purposes to make this town his constant residence, and to use every means in his power to bring the young ladies and gentlemen forward in their dancing who are placed under his tuition. He likewise intends teaching French. . We can only assume that this Mr Gardiner was our S. J. Gardiner and not some other dancing master with a similar name. Moving to Shrewsbury after performing in London is a career path previously associated with the celebrated John Weaver (1673-1760); Weaver was one of Britain's more important dance writers of the early 18th century, it's possible that Gardiner was knowingly and deliberately following in Weaver's footsteps.

Gardiner evidently offered tuition at a local school. He included an anecdote within the preface of his book complaining of a school governess who had rejected his offer of tuition, perhaps even the same Mrs Watkis at whose school he intended to teach in 1773. He was evidently unhappy about the rejection. Most further details of his life and work remain conjecture at this point however. It was not unusual for stage performers to retire into dance tuition when they left the stage, or to move away from London to settle somewhere else; how he came to Shropshire is unknown, so too is his age at that date. He might have been an older man by 1786; the tuition he offered to the English nobility probably occurred in Italy back in the late 1750s or early 1760s, he might have been in his twenties or thirties at the time - he was probably in his 50s or 60s (or perhaps older) by the date of publication. The book will represent reflections on his career over several decades.

Since beginning to write this paper I have become aware of an existing book investigating Gardiner's life and work, it is Madeleine Inglehearn's excellent 1997 The Minuet in the Late Eighteenth Century. Inglehearne offers several further insights into Gardiner's life that I shall not reproduce here, suffice to say that anyone wanting to know more would be well advised to read her wonderful book.

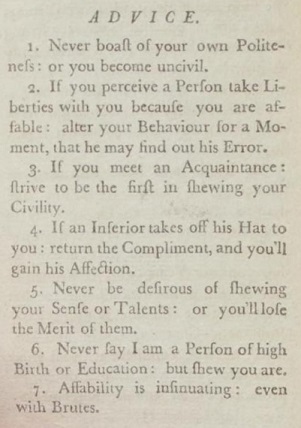

Figure 3. The first page of Gardiner's general Advice.

Gardiner's A Definition of Minuet-Dancing

Gardiner's book takes the format of a dialogue between a Dancing Master and a Lady. The Lady asks questions that the Dancing Master answers over the course of some 61 pages. Until relatively recently it was a difficult work for enthusiasts to access, that is no longer the case thanks to the ongoing digitization work of the British Library and their partnership with Google Books (see Figure 1). The British Library's copy was scanned in 2019 and is now available on the web for anyone to read who cares to do so. The reader might wonder why, given that the book is readily accessible, we have decided to provide a transcript here. The Google digitization process is imperfect and at time of writing their scanned text (as used by their search engine) is largely unusable. Providing a clean and correct transcription here will hopefully aid researchers and enthusiasts in finding and reading Gardiner's book for themselves.

The book begins with a preface in which Gardiner acknowledged that some dancing masters taught incorrect variants of the Minuet, this would lead to confusion in the ball room. His book aimed to correct that situation. He also referred to the importance of teaching dancing in schools. He ended his preface with an apology for his imperfect spelling and grammar within the book; I've attempted to leave his more peculiar use of accented characters, capitalisation and spelling as he himself supplied them. Minor errors have been corrected in the transcript where they were sufficiently obvious and uncontroversial.

The main content of the book begins with a section on the positions of the feet (4 pages), then continues on to walking (2 pages), bending and rising (1 page), beating time (1 page), courtesies and bows (5 pages), the Minuet (22 pages), stage dancing (3 pages), behaviour (8 pages), Cotillions and Quadrilles (4 pages) and ends with a section on general advice (4 pages). The section on the Minuet dance is by far the longest individual section but it makes up less than half of the total book. Most of the content relates to graceful motion and behaviour, whether in the dance or elsewhere. The Minuet is thereby placed in context as one of many skills that the young gentleman or lady should practice. An 18th century dancing master would be employed to teach more than just dancing.

As far as I can discern Gardiner's book was a product of his own mind and not copied from elsewhere. He was evidently influenced by the Minuet guides of the early 18th century but his words and ideas were his own. His closing advice on polite behaviour is of particular merit, it consists of a set of maxims that any reader ought to take to heart, many would still be considered appropriate for a modern audience. The first page of Gardiner's advice to the reader can be seen in Figure 3.

Minuet Dancing in the 1780s

The Minuet dance had been a part of the courtly dance tradition in Britain across the 18th century, it's immediate origins can be traced back to France. Many generations of Georgian nobility had received tuition in dancing the Minuet, dancing masters taught the movements along with those graceful accomplishments that were considered of necessity to a professional courtier. Most of the surviving books that describe how to dance the Minuet date from the early 18th century (at least those written in English), Gardiner's text is unusual as it offers a late 18th century insight into the British tradition.

Figure 4. A view of the ball at St James's on her Majesty's birth night, 1782 (left), a Minuet dancing couple from a 1782 fan (right). Left image is courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, right image is courtesy of the British Museum.

Before going further I must acknowledge that I myself am not a Minuet dancer, I've relied upon the observations of others in order to write about this dance. I am particularly indebted to Barbara Segal for her assistance in investigating the forms and historical context of the Minuet dance (any errors do of course remain my own).

The Minuet was the ceremonial dance that opened Britain's formal balls of the later 18th century. Pairs of dancers would perform their Minuet under the observation of their peers; the dance involved a sequence of specific steps, the dancers would demonstrate their grace, elegance and general deportment to the admiring audience. An example image of a Minuet dance at the Queen's Birthday Ball of 1782 can be seen in Figure 4. The dance was unforgiving, a poor performance in the Minuet would have been very obvious. It was, in a sense, the antithesis of the Country Dance: where the Country Dance promoted enthusiasm and tolerated a lack of preparation, the Minuet required the perfection achieved through perseverance. If a dancer couldn't perform the Minuet with perfection then they wouldn't risk a public performance at all, whereas a talented Minuet dancer might become a favourite at court. The form of the Minuet was standardised but dancers could inject a degree of improvisation into their routines (within the accepted framework), the length of the dance could be varied by repeating the main figures and grace steps might be introduced. The Minuet was typically performed as a slow and deliberate dance, it could however be danced quickly in some contexts. Back when the Minuet first emerged in France it had been a lively dance, it was performed much faster than the Courante (the ceremonial dance of the time); by the 1780s the Court Minuet was performed slowly, though stage dancers were likely to have danced it at faster speeds. The Minuet is a dance associated with the baroque splendour of the courts of Louis XIV of France (1638-1715) and of Charles II of England (1630-1685), dancers of the 1780s would likely have thought of it as an old fashioned and formal dance.

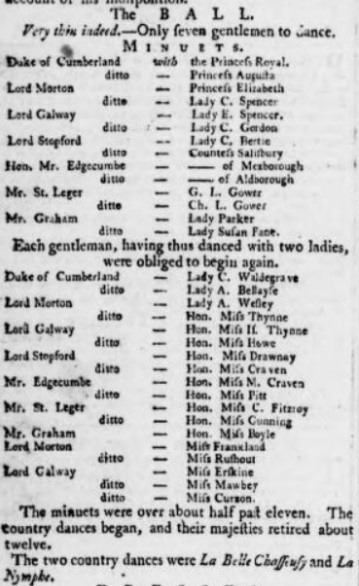

A challenge for the court Minuet Balls of the 1780s was in finding sufficient gentlemen willing and able to dance the duets. The supply of willing gents was sufficiently limited that most gentlemen were expected to dance the Minuet twice in a row with different partners, at some events even this was insufficient. The Stamford Mercury newspaper for the 8th of June 1787 printed the list of Minuet dancers at the King's Birthday Ball in London that year, only seven men were willing to dance and so most of them partnered with four ladies over the course of the evening (see Figure 5); whereas, Lord Morton (1761-1827) was required to dance Minuets with six different partners and Lord Galway (1752-1810) with seven! Not all balls were quite so constrained, the Stamford Mercury (25th of January 1788) reported on another court ball in which eleven gentlemen danced (including the Prince of Wales himself), it was only Lord Burford (1765-1815) who was required to dance with four different Ladies on that occasion. These performances would involve a single couple dancing at a time, perhaps for three or more minutes, before the assembled company. It was only when the entirety of the Minuet dancing was complete that the Country Dances could start, there may only be time for one or two such dances towards the end of these formal events.

Figure 5. The King's Birthday Ball programme from the Stamford Mercury, 8th of June 1787. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive ( www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

G. Yates in his 1829 The Ball; Or, A Glance at Almack's wrote (based on personal experience) of his memories of the Court Minuet of our period:

On the evening of the ball, the Lord Chamberlain, with his wand of office, stood within the railing that encompassed the space for dancing, with the list of dancers in his hand. When the ball-room was as full as was thought convenient, the door of entrance for the company was closed till the ball was over; and when their Majesties some little time after entered by another door, the yeomen and gentlemen pensioners quitted the room, having previously stood at the barrier that enclosed the space reserved for dancing. On their Majesties entrance the court band, stationed in the music gallery at the opposite end of the room, commenced playing the march in Judas Maccabeus, which by the king's command was always performed on this occasion.

After their Majesties had walked round the inside of the space set apart as before mentioned, and had spoken a few words with those of the nobility that were near enough, they retired to their chairs, (for there was no throne) and this was the signal for the band to cease. Then the Lord Chamberlain advanced to the Prince of Wales and his royal sister, making his obeisance before them, on which they arose and performed the same ceremony before their Majesties, retiring backwards until they arrived at the opposite end of the open space, when the band immediately commenced playing a minuet.

The court dancing-master (Monsieur Desnoyer) spread the lady's train, which was exceedingly long and heavy with gold or silver, and which, during the respectful preliminary, had been supported on the hoop. Having concluded a minuet, the obeisance was repeated to their Majesties; and in the same manner proceeded the other members of the royal family and nobility according to precedence, going through the same ceremonies.

The gentleman did not go up a second time to make obeisance if he was again required to dance another minuet (as was generally the case); but waited for another lady, who was under the necessity of going through the awful ceremony alone.

The formal court Minuet followed a carefully proscribed ceremonial procedure when danced at St. James's Palace. The experience of Minuet dancing at private balls might have been a little less formal, it would still echo the court traditions with polite deference being shown to the host.

Several variations of the Minuet were performed at the Theatres of the 1780s. The Norfolk Chronicle newspaper for the 31st of March 1781 reported of a Ball at the King's Theatre where Messrs Vestris, sen. and junior, Madam Simonet, et. al. made their appearance at one o'clock, and performed several dances, besides the new minuet composed by Signor Vestris, sen. in honour of the amiable Duchess of Devonshire, and called the Devonshire Minuet, which was received with astonishing marks of applause . This performance by the professional dancers of the theatre was probably a theatrical divertissement to entertain the ball guests. The Devonshire Minuet immediately entered the repertoires of the Dancing Masters after this debut, it would be taught until at least the 1820s. G. Yates in his 1829 The Ball; Or, A Glance at Almack's wrote of Vestris' performance of the Devonshire Minuet: Of this minuet, though very plain and simple, he made most profitable account by receiving ten guineas from every professor who desired to acquire it, which was almost universally the case from the fashionable and extensive repute of the dance. The author's father was amongst the company on the above occasion, and attended Vestris the next morning in order to obtain the earliest professional advantage of his minuet, and be the first to introduce it in his various schools, where it was then the usage to pay extra for all that was new. . One particularly successful Minuet variant was the Minuet de la Cour, it was a Parisian dance that swept the nation from around 1777, it would be routinely mentioned in the advertisements of dancing masters thereafter; Gardiner explained that it is a well composed graceful Dance but didn't discuss it any further. There were a huge range of steps available from which the professional performers could draw when performing a Minuet, they might even perform whole turns in the air. These theatrical Minuets were unlikely to have been danced by the nobility at the Court Balls, they were intended to demonstrate the skill of the stage performers. Other Minuet-like dances that Gardiner acknowledged to exist in his book include The Louvre, the Courente la marriéz, Bretagnie le paspied, Minuet Danjou, Charment, Vainceur, and several others: but none of these graceful Dances are in vogue in England at present . Gardiner recommended the study of Corégrafie (choreography) in order to learn such dances from their published sources.

The Minuet fell from favour as the 18th century progressed, by the start of the 19th century it was not widely danced. The King's annual Birthday ball, the Lord Mayor's annual Ball and other particularly formal events might continue to include them, but the Assembly Rooms had largely abandoned them. We've shared a transcript of F.J. Lambert's 1815 Treatise on Dancing in a previous paper, to some extent it continued the story of the Minuet; Lambert wrote that the minuet is not now danced in public, except at court . Another commentator of interest is Frances Maria Elliston Wilson; Wilson was the daughter of the celebrated dance mistress Mrs Elliston (d.1821), Elliston was was in turn a student of Miss Flemming (c.1745-1823) and Flemming the daughter of Madame Roland (c.1714-1759) (all three of whom were celebrated teachers of dancing in Bath). Wilson published her Fashionable Court Minuets in 1845 and wrote of the Court Minuet that: This Minuet, so much in fashion at the Court of George the Third, was danced at that period with rather sudden bends of the body, and risings on the toes, owing to the peculiarity of the prevailing costume, which consisted of the hoop petticoat and high-heeled shoes: ... During the reign of George the Fourth, the Minuet was not performed at Court; but the practice of it being found of such importance in giving elegance and dignity to the carriage, the late Mrs Elliston continued to teach it to her pupils, many of whom are now moving in the higher circles, and remember the graceful style in which it was danced by her, in full Court dress, at her annual public balls . The Minuet may have fallen from favour in the early 19th century but it wasn't forgotten.

Many assembly rooms still permitted ladies of precedence who wished to dance a formal minuet to do so, at least up until the end of the 18th century. A report in the Courier newspaper alluding to the Balls held at the Bath Assembly Rooms in 1804 (20th December 1804) noted that It was formerly the practice for the opening of the Dress Balls here to be distinguished by minuets; but this custom seems now totally exploded; and the more merry notes of a Scotch or an Irish jig generally begins and ends the graceful diversion . The final court Minuet Ball to be held at St James's Palace was announced in the Gazette by the Lord Chamberlain in 1802. Some 23 years later, The Courier newspaper for the 25th of July 1825 wrote: Yesterday the first Grand Entertainment was given by his Majesty at St James's, ... [it] is the first of the kind which has taken place in that Palace for twenty-three years past, when the late King and Queen had their last Ball there, at the celebration of the late King's birth, when Minuets were in fashion, and when Public Balls were given by their Majesties at the celebration of both Birth-days after the Drawing Rooms, at which all those who were in the habit of attending Courts were admitted. These Assemblies were discontinued owing to the declining years of their late Majesties, and other circumstances. No public or state use has been made of this venerable pile for a number of years. [I'm indebted to Cassiane Mobley for the discovery of that statement]. The Minuet had declined in use by the start of the 19th Century, a question remains about the role of the Minuet in the Assembly Rooms in the 1780s however; a new and mysterious phenomenon had emerged named the Long Minuet , we'll investigate this dance in just a moment.

If you'd like to read more of the Court Minuet Balls of the 18th Century then I can recommend Hillary Burlock's essay Tumbling into the lap of Majesty : Minuets at the Court of George III which is available on-line courtesy of the Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, you might like to follow the link to read more.

The Long Minuet of the 1780s and 1790s

References to the long minuet surface at the end of the 1770s. It's not entirely clear what this dance was, only that it was associated (at least at first) with the Assembly Rooms at Bath. One early reference can be found in the Bath Chronicle newspaper for the 18th of March 1779, the column was reporting on an elegant and sumptuous breakfast ... given in compliment to Admiral Keppel, by twenty-five Ladies of the first distinction in this city ; the entertainment was given at the New Assembly Rooms and The youthful part of the company continued dancing cotillons and country dances till after three o'clock, when the entertainment finished with a long-minuet, composed and presented on the occasion by a young Lady of distinguished worth and musical abilities . This initial reference to a long-minuet might hint at either a musical interlude or an especially long (in duration) minuet dance. Readers were expected to understand what the term implied, it was presumably a concept that was already current amongst the Bath faithful. The challenge we have in discussing the Long Minuet is that we only have fragments of information from which to reconstruct the nature of the dance. One possibility is that the Long Minuet was danced by several couples at the same time (perhaps performing in a long line); a letter dated December 29th 1778 written by John Wilkes (1725-1797) to his daughter offers some credence to this idea; Wilkes wrote of the dancing at Bath that: We had a most superb ball at the upper rooms last night, my dear Polly, and the minuets are now danced three deep, so that they are finished in an hour and a half. The concept of multiple minuet dancing couples performing at the same time could have received the name long minuet .

Figure 6. Bunbury's 1787 A Long Minuet As Danced At Bath.

A passing reference to the long minuet can be found in the August 1788 edition of the Gentleman's and London Magazine where we read in a satirical passage that compared ministers of the church to dancers: in our annexed plate we have to be sure only given a long minuet - such as is generally danced at Bath, and other watering places . This passage seems to confirm that the long minuet was associated with Bath, though it was also known at other spa towns (we'll return to discuss the associated plate in just a moment). A notice printed in the Bath Chronicle for the 6th of December 1792 reported that the Fancy Balls at Bath would: commence with a Country Dance, after which there will be one Cotillon only and then Tea. After Tea, a Country Dance, One Cotillon, and the evening to conclude with Country Dances, and the Long Minuet . As with Admiral Keppel's breakfast over a decade earlier, the Long Minuet of 1792 appears to have been intended for the end of the evening. It might perhaps have been a finishing dance, something to allow many participants to dance together one final time before leaving to go home. But what was the dance? It could have been a long piece of music in which as many couples as desired could dance a Minuet either concurrently or in immediate succession, it could have been a Country Dance arranged in Minuet time and danced with Minuet steps, it might have been a courtly Minuet danced by the most important couple in the room in order to close the Ball. Other possibilities can also be imagined, sadly Gardiner didn't comment on this subject.

The most famous reference to the Long Minuet involves a caricature image that was published in 1787. Henry Bunbury (1750-1811) published his A Long Minuet As Danced At Bath to immediate success (see Figure 6); it was well over two meters in length and depicted ten couples in various stages of dancing. Many copies were sold and the print became one of his most popular works (the annexed plate of 1788 referenced above was a reprint of part of Bunbury's image). The image was intended to be amusing, many of the characters depicted look awkward or foolish. As an example of how the image was received we can consider the 1791 Eccentricities of J. Edwin where we read: I presented him with Mr Bunbury's excellent caricature of the long minuet , and he was so pleased with the ludicrous variations of adopted grace in the different characters, that he pinned it in his study, and frequently marshalled his scenic demeanour from the graphic example . The comic actor evidently used Bunbury's image as inspiration for his own performances. The 1811 Literary Panorama described Bunbury's Long Minuet as a piece of incomparable humour ; a footnote in the 1805 European Magazine noted that Bunbury's dance was rendered remarkable by the monstrous strides and contortions of its members, and by the many false steps which they were continually taking . Bunbury's image doesn't depict a successful performance of the Minuet, it instead shows couples failing in their attempts to be graceful.

But what does Bunbury's image reveal of the Long Minuet dance? It could imply that several couples would perform the long minuet together (note how a gentleman from one couple is stood on the dress of the Lady from the next). It might imply that the performers were not from the upper echelons of the British Aristocracy, rather they're made up of the myriad subscribers to the Bath Assembly Rooms. An interesting text from 1799 perhaps offers some insight. Blundell's 1799 Dancing Masteriana includes a comic account of an Alderman being coerced into dancing a series of dances, it then continues: I have thought to aid the exhibition, by a caricature in the style of Bunbury's long minuet: the two minuets will fill the first half sheet, the hornpipe and cotillion the second, and the third will be left for the concluding figure . This adds credence to the idea that the ten couples in Bunbury's image would have danced in succession rather than concurrently.

Bunbury's caricature was so popular that many later references to the Long Minuet refer to his image rather than to the original dance. The Long Minuet, whatever it was, may have hastened the decline of Minuet dancing in general. The poet Catherine Fanshawe (1765-1834) in her 1820 The Death of the Minuet wrote of the final days of the Minuet dance:

...

What cause untimely urg'd the Minuet's fate?

Did wars subvert the manners of the state?

...

While Fancy sketch'd, and Humour group'd,

Then it sicken'd, then it droop'd;

Sadden'd with laughter, wasted by a sneer,

And the long Minuet shorten'd its career!

...

No ball to night! Lord Chamberlain proclaims,

No ball to-night, shall grace thy roof, St James,

...

So Power completes, but Satire sketch'd the Plan,

And Cecil ends what Bunbury began.

The Long Minuet (whether Bunbury's image or the dance itself) made a joke of the Minuet dance. Fanshawe suggests that once people began laughing at the Minuet, and at the figurants who danced the Minuet, the dance fell from favour. It was ultimately dropped from the formal Court Balls by the Lord Chamberlain (James Cecil, 1748-1823) in 1802. The Minuet had been unable to survive open ridicule. Power, according to Fanshawe in the closing couplet of her poem, ended the Minuet though satire had sketched the plan, the Lord Chamberlain completed what Henry Bunbury began. The decline of the Minuet may have started around the date that Bunbury published his image in the late 1780s, it accelerated into the 1790s and the Minuet was rarely danced by the start of the 19th century.

It's unfortunate that the details of the Long Minuet as a dance remain so vague, if you have any additional information to share on the subject then do please Contact Us as we would love to know more.

One final thought, before leaving this subject, involves a word of caution offered by William Hogarth in his 1753 The Analysis of Beauty; Hogarth (referring more of a Country Dance than to a Minuet) pointed out that even the most elegant of dancers are liable to look a mess if a picture of them were to be captured mid-dance. He wrote: The best representation in a picture, of even the most elegant dancing, as every figure is rather a suspended action in it than an attitude, must be always somewhat unnatural and ridiculous; for were it possible in a real dance to fix every person at one instant of time, as in a picture, not one in twenty would appear to be graceful, tho' each were ever so much so in their movements; nor could the figure of the dance itself be at all understood. . Perhaps Hogarth was imagining a future where a photo of a dance could be captured mid performance!

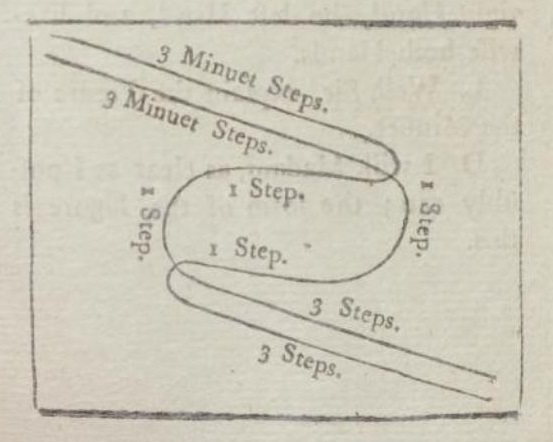

Observations from Gardiner's Book

Gardiner published his book towards the end of the 18th century, the style of dancing described is mostly consistent with the equivalent books published in the early 18th century. He describes the main Minuet figure as involving nine steps but offered a variant in only eight; he suggests that it is the Lady who decides when to change the figure and to present hands, a subtle contradiction to earlier conventions. Gardiner describes the traditional letter Z track of the Minuet and also a Modern track in the form of a reversed letter S . These subtleties may be of some interest to modern Minuet dancers.

Writing as someone who prefers Cotillion dancing to the Minuet, I personally find Gardiner's observations on the Cotillion to be fascinating. It is disappointing to me that he didn't have more to write on the subject. The observation I quote most frequently from Gardiner relates to the Quadrille dance of the 1780s, Gardiner explained: They are Danced the same as the Cotillions, only with this difference, that instead of four Couple in the Cotillions, there are but two in the Quadrilles. . A detailed discussion of the early Quadrille would be out of place here, it's something we have written about elsewhere however, you might like to follow the link to read more.

One minor observation I find curious is Gardener's opinion on choreographic notation: a Number of the capital Masters don't trouble their Heads about it, but I think it proper a Country-Master should know it lest he should be at the Trouble and Expense of going to London to learn every new Dance that comes out . The choreographic notation used for Minuet dances was something, according to Gardiner, that rural dancing masters had a greater need for than those in the city. He may of course have been pointing out that his own education was more complete in this matter than that of some of his local competition.

Let us now proceed to the book itself. What follows is a complete transcription of the work. There are minor edits for formatting reasons, such as moving the images to the side of the text, or combining partial words that were split across lines. It is otherwise a faithful transcription.

Transcript of the Book

A DEFINITION

OF

Minuet Dancing,

RULES FOR

BEHAVIOUR in COMPANY &c.

A DIALOGUE

Between a LADY, and a

Dancing-Master

By S. J. Gardiner.

MADELEY

Printed by J. Edmunds

The Preface

The Art of Dancing is so fashionable an Accomplishment in this Kingdom, and in all civilized parts of the habitable Globe; that it is almost impossible for a Gentleman or Lady to appear with a proper grace without it.

And indeed the Advantages that arise from it are many. A Gentleman or Lady cannot even enter a Room, make a genteel Bow or Courtesy, or walk graceful and polite, without being instructed in this essential part of Education.

The Minuet is an antient and universal Composition, and is approved of in all parts of Europe, and danced in the same Manner (some few Graces excepted) by the polite Inhabitants of every part of the World, as it is in London or Paris; yet we frequently hear young Ladies and Gentlemen say one to the another Your Master does not teach the same Minuet as ours. By what I have said before it will appear that there cannot be a greater Absurdity: but I rather suppose if there is an Alteration, it proceeds from Ignorance, for there are numbers of pretended Dancing Masters in this Kingdom who send out Bills and inform you that they can teach the Minuet, Minuet de la Cour, Gavots, Cotillions, Quadrilles, Country Dances &c &c . They know the Names of these things, can scrape a little upon the Violin, get a fine Coat, and commence Dancing Masters. These kind of Gentlemen sadly impose upon the Public; but I have endeavoured in this little Work to explain the Minuet in as easy and clear a Manner as I possibly could, that Parents may know such Gentlemen and save their Children from being spoiled by them

Young Gentlemen or Ladies who have learned their Positions, may easily, with studying this Book and practising, attain to a perfect Knowledge of the Minuet.

I have endeavoured likewise, to explain the true Method of making a Bow or Courtesy, and to enter a Room properly; and have laid down Rules for Behaviour, in almost all sorts of Company: which will (I hope) be found beneficial to those who have not had the Advantage of a good Education, or neglected embracing the Opportunity of improving themselves when it offered.

Masters and Governesses of Schools, that have not an Opportunity of having a Dancing Master (or perhaps don't approve of having one) will certainly reap great Advantages from it: for though the Art of Dancing (as I have said before) is allowed to be quite requisite by most sensible and judicious People, yet I have known some Master and Governesses of Schools so bigotted, as not to permit a Dancing Master to attend their Pupils; an Instance of this I had lately myself, which I'll beg leave to insert. I sent some Hand Bills some small Time since to a Governess of a School in Shropshire, which inform'd her that I was come to reside in the Neighbourhood, and should be glad to take a Part in the Education of her Pupils; she readily receiv'd the Bills, but upon second Thoughts sent them back the next Morning, with a Note, wherein she sent her Respects to me, and hoped I would not take it amiss; for it was contrary to her Principles to promote that Accomplishment. She acknowledges it an Accomplishment, but at the same time she says it's contrary to her Principles to promote it! I did not know it was proper for a Governess, to deny her Pupils any Accomplishment that would be beneficial to them, especially if their Parents approved of it. But in my Opinion those Principles must be very extraordinary, that forbid being Humble, Meek, Polite, Genteel, Affable and Modest; and I should think very unfit for a Governess of a School, if she has any Intention of doing Good for her Pupils.

If it is not necessary, why do so many Noblemen and Gentlemen in this Kingdom, as well as abroad encourage it? and why do the most capital Masters and Governesses in this Kingdom permit it to be taught in their Schools? The Answer is, because they think it very requisite for the Accomplishment of a Lady or Gentleman; with that Intent I wrote this little Book, and I hope it will be found to answer the Purpose.

A great Number of Faults, I am afraid, are committed in it, but the Critic will do well to remember, that I am a Dancing Master and not a Grammarian. I hope he will therefore generously look over some trifling Errors; and if there is any part of it commendable, he will notice it, as my chief Design was to explain what I have written upon as clearly as possible.

Madeley 1786

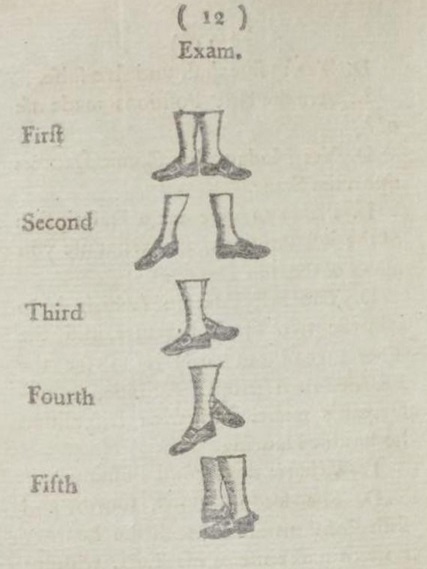

Figure 8. The five just positions in dancing. Page 12.

A Definition of Minuet Dancing

Of the Positions &c.

Lady: Are you a Dancing Master?

D: I am; nor do I well conceive Madam, why you question it.

L: I question it because many have been deceived by Gentlemen of your Profession.

D: I grant it Madam, but not if they were Judges.

L: Why so?

D: Because a Judge will know a good or bad Master by the performance of his Pupils, or by inquiring into his Abilities.

L: Suppose he is found deficient, and has no other Way of getting a Livelihood; is this poor Man to perish?

D: My endeavouring to give so plain a Demonstration of the Art of Dancing, is an infallible Proof, that I am desirous of his Prosperity.

L: Pray how can you make that appear?

D: This little Book well studied, will make him leave off being any longer an Impostor.

L: Please to explain what is necessary to be known, for a Man to be a complete Master of this Art?

D: He should know from the Positions, to the greatest Difficulties performed by any Master, if he cannot execute them himself he ought (at least) to give a Definition of every Movement performed in that Composition; be it Stage-Dancing or Civil-Dancing.

L: How many Positions are there?

D: Ten: five just and five false.

L: Are the false Positions made use of?

D: Yes Madam, by Comic-Dancers upon the Stage.

L: Please to give me a Description of the just Positions, and what use you make of them in Dancing.

D: The first Position (which is to join the two Heels together, and the Toes turned outward) is to see the Learner in a proper Attitude, to observe his make, and what Disposition he has for Dancing.

L: What is the second Position?

D: The second, third, fourth, and fifth Positions are to teach the Learner how to make use of his Legs, without disturbing the Attitudes of his Body.

[Figure 8 depicting the five just positions is inserted here]

L: Pray Sir, when the Positions are properly understood, what is to be learned next?

Of Walking

D: The Pupil must learn next to walk in a genteel Manner.

L: What do you call a genteel Manner?

D: The Head must be straight, the Chin drawn back without Stiffness, the Shoulders a proper fall, the Body perpendicular, and the Knees and Toes turned outwards from the Body.

L: Well, but Sir this is not walking.

D: No Madam, but it is preparing for it.

L: Is there so much Preparation necessary for walking only?

D: Yes Madam, and if a Person does not walk well, he can never pretend to be graceful or easy in Dancing.

L: Very well, Sir, please to proceed.

D: The Learner standing in the first Position, must lift up his right Foot, with his Toe pointed towards the Ground; then put it down in the fourth Position, and in a soft easy Manner let his Body come upon it: the Foot that remains behind should be lifted up soft, and easy, and not extended till he's going to put it down in the fourth Position, as he did with the right Foot; the Body carried upon it as before mentioned; let the Pupil proceed so, and he walks properly.

L: Well, Sir, I understand that walking is difficult.

D: Yes Madam, and unavoidably necessary for Dancing well.

Of Bending and Rising

L: Well, when the Pupil has learned to walk straight, graceful, easy and proper; what is to be done next, pray?

D: He must be returned to his first Position, and learned to bend and rise in a supple, soft manner; thus, He must stand in the first Position, and keep his Body straight, then bend in a soft Manner, rise the same, and when the Knees are extended, he must rise upon his Toes, keep his Knees stiff, then let his Heels go softly to the Ground; and so do the same over again, till the knees become supple.

L: Pray, Sir, what is the Use of bending and rising so much?

D: By bending and rising, the Learner comes to dance supple, and besides, it is an Advantage to a Lady for making a Courtesy in a genteel Manner.

Of Beating Time

L: Pray, Sir, do you make them beat time?

D: I do, Madam but in a different Manner to what is commonly taught.

L: In what Manner do you teach them?

D: I teach them to beat to every Note that is in a Bar of Minuet-Time, next to every Bar; and lastly to every two Bars of the Music.

L: What Advantage is it to beat to every Note?

D: It opens the Ear to the Music, and sometimes of a bad Ear makes a good one; at least through constant Practice it improves a bad Ear greatly.

Of Courtesies and Bows

L: Will you be pleased to explain the Courtesies and Bows, Sir.

D: Yes, Madam. When a Gentleman or Lady goes in, or comes out of a Room to avoid Aukwardness or Affectation, they must absolutely be acquainted with the following Rules. At a Gentleman or Lady's first Appearance in Company, they must avoid Bashfulness, and put on a modest smiling Countenance; the Lady should walk two Steps forward, to get from the Door, and the Foot that is behind after the second Step, should be brought softly to the third Position behind; then the Lady must courtesy, bending her Knees outside, and casting a modest Look with a little Turn of her Head round the whole Company.

L: Pray Sir, is one Courtesy sufficient for a whole Company?

D: If the Lady fees Acquaintances placed in any Part of the Room, she must make Passing-Courtesies to them.

L: How is the Passing-Courtesy made?

D: If the Person the Lady means to Courtesy to, is placed on her right side; the Lady that enters the Room must place her left Foot in the fourth Position forward as she walks; then turning her Face towards the Person, draw her right Foot to the third Position forward, and bend her Knees; but not much in a Passing-Courtesy. If there should chance to be another acquaintance on the left side, she must walk one Step only with her right Foot to the fourth Position forward, turn her Face on the left side, and draw the left Foot to the third Position forward, and then make the Courtesy; it must be observed that the Lady should always walk the first Step after the Passing-Courtesy, with the Foot that she draws to perform the Courtesy; and must endeavour to avoid Affectation, Stiffness, and Aukwardness.

L: Well Sir, please to inform the Lady how she is to place herself in the Room.

D: I design it Madam; the Lady should walk in an easy Manner to the Place that is intended for her; then sit down without bending her body too much, and yet must take care to avoid Stiffness.

L: How is the Lady to go out of the Room, Sir?

D: In the same Manner she comes in, except when she has finished her last Courtesy towards the Door, she is to walk one Step backward, before she turns to go out.

L: Very well, Sir, now I should be glad if you would please to inform me how a Gentleman is to enter a Room.

D: When a Gentleman goes into a Room, he must stand in a straight Posture, and turn his Head to view the whole Company, at the same time he must carry his right Foot to the second Position, then lift up the Heel of his left Foot, and draw it almost to the first Position, bow his Body at the same time, with his Head down, and when his Body is risen again to the first Attitude, the Foot that he drew must go to the fourth Position behind, and then walk on with the right Foot.

L: Suppose the Gentleman has an Acquaintance sitting at his right for left Side; how is he to behave then?

D: He must make Passing-Bows to him.

L: But, pray, how are the Passing-Bows made?

D: The Gentleman, the same as the Lady, except that he bends his Body to Bow, and she bends her Knees to Courtesy.

L: I should be glad to have a clearer Explanation of these Passing-Bows, if you please, Sir.

D: I will explain them as clear as I can, Madam. After the Bow to come in to the Room, if the Gentleman sees an Acquaintance placed at his left Side, after his first step in finishing the Bow to come in, the right Foot being in the fourth Position forward, he must turn his Head to the left Side, and look at the Person be is going to Bow to; then make a little Inclination of his Body towards the Person, with his Head downwards, he must at the same time draw his left foot betwixt the third and fourth Positions forward, and walk on to his Place with the same Foot that he draws, and then sit down in an unaffected way. The right side is done in the same Manner.

Of the Minuet

L: Now, Sir, will you be pleased to explain the Minuet?

D: I will, Madam. In an Assembly, if a Gentleman chuses to dance a Minuet, he should get up from his Place in an easy graceful Manner, with his Hat in his left Hand, and approach the Lady he intends to dance with; he must then make his Obedience to her, and ask her if she pleases to dance a Minuet with him; if she refuses, the Rule is, that she cannot with Propriety dance with any other Gentleman for that Assembly.

L: Well, but suppose the Lady does not refuse?

D: If she does , the Gentleman must then take the Lady's left Hand with his right, and lead her to the Place where they are to begin.

L: Very well, Sir, now please to inform me how they are to begin the Minuet.

D: The Lady must place her left Foot in the third Position forward, her Hands placed one upon the top of the other across the Waist; she must then open her Arms sideways, and rather slow, then lay hold of her Gown on each Side with her first Finger and Thumb of each Hand, the other Fingers must be bent a little (except the little ones, for they must be quite straight.) The Gentleman must place himself in the third Position, with his right Foot forward, his Hat in his left Hand, and about a yard distant from the Lady; before he begins to Dance he must put his Hat on, then the Lady and he must Step out to the second Position towards one another; the Lady must make her Courtesy the same as when the enters a Room, and the Gentleman likewise his Bow, except at the ending of the Courtesy the Lady must put her right Foot to the fourth Position behind, then point her left Foot in the fourth Position before, with her Body turned towards the right, and her Face towards her Partner. The Gentleman must put his left Foot to the fourth Position behind, then point his right Foot in the fourth Position before, his Body towards the left, and his Face towards his Partner.

L: But pray, Sir, what is the Gentleman to do with his Arms all this time?

D: In the Bowing he must let his Arms hang loose, as if he had no Use of them, and when his Body is straight, his Arms must hang loose upon his Sides, and his Hands must be turned a little outwards.

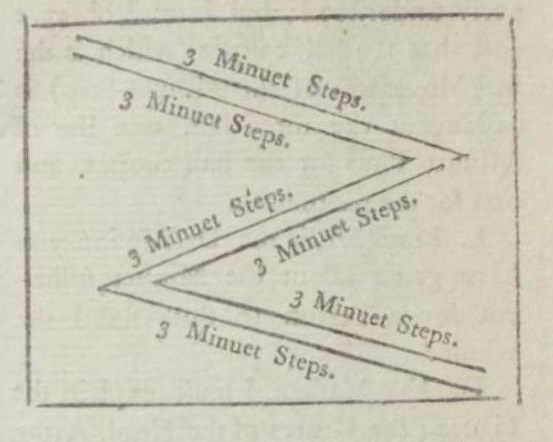

Figure 9. The 'Z' form of the Minuet figure, danced with 9 Minuet steps. Page 30.

L: Very well, Sir, please to go on.

D: We have left our Dancers at the End of the first Courtesy and Bow, and now, Madam, we will proceed to the second. The Lady who stands with her left Foot in the fourth Position forward, is to slide it about two Inches beyond the fourth Position, the Gentleman must do the same with his right Foot; they are then to turn upon that same foot, and bring the foot that is behind to the first Position, and face one another; the Lady must then Step out with her right Foot to the second Position, and the Gentleman the same with his left; the lady must draw her left Foot to the first or third Position behind, and make a Courtesy to her partner, and at the same time the Gentleman must draw his right Foot almost to the first Position with his Toe pointed, and make his Bow: please to observe that the Courtesies and Bows must rise again very slow.

L: Well, but you are very long explaining the Courtesies and Bows.

D: If I don't explain myself a little intelligibly, Madam, I shall not be understood. But to proceed, the second Courtesy and Bow are to be finished in the same Attitude as the first, except that the Lady is to have her right Foot forward, and the Gentleman his left.

L: Now please to proceed to the Dancing part.

D: The Lady then is to make a Demiecoupéz forward with her right Foot, and the Gentleman is to make a Demiecoupéz sideways with his right Foot, the Lady must then make a pá tombéz with her left Foot, and the Gentleman a pá de bouréz with his left Foot.

L: But pray Sir, what is the meaning of this Demiecoupéz pá tombéz, and Demiecoupéz pà de bourèz.

D: A Demiecoupéz forward is to bend your knees in a Position to slide your right Foot to the fourth Position, and bring your left Foot to the first. A pà tombéz is to put your left Foot in the second Position, then mark the second Position with your right foot, let it go behind the left to the fifth Position, bend your Knees a little, and put your left Foot to the second Position. A pà de bouréz is to stand in first Position, and bend; then slide the left Foot to the fifth Position behind, and rise upon your Toes; then walk with the right Foot in the second Position, and the left to the fifth behind; and that finishes the pà de bouréz.

L: Pray give me a Definition of the Minuet-Step forward.

D: The Minuet-Step forward is composed of a Demiecoupéz and pà de bouréz forward.

L: Very well Sir, but those French Terms are not to be understood by everybody.

D: I'll make them clear Madam, to any Persons that have learnt their Positions.

L: Pray let me hear you, Sir.

D: The Learner standing in the first Position must bend his Knees, and slide his right Foot to the fourth Position, then bring his left Foot to the first Position, and that finishes the Demiecoupéz.

L: How is the pà de bouréz performed?

D: In the Minuet-Step it is done with the left Foot, which is thus, the Learner must bend his Knees in the first Position, and side his left Foot to the fourth Position forward; then he must rise and walk two Steps upon his Toes, with his Knees extended, to the fourth Position with the right Foot, and to the fourth with the left, which ends the Minuet-Step forward.

L: I should be glad, Sir, if you'd give a clearer Demonstration of the right and left Side-Steps in the Minuet,

D: I will, Madam. The right Side-Step is a half coupéz Sideways, and a pà de bouréz Sideways; the half coupéz is for the Learner to bend his Knees with his right Foot in the fifth Position behind, then slide his right Foot to the second Position, and draw his left Foot with his Heel up to the first Position, and that finishes the half coupéz.

The pá de bouréz Sideways is performed in this manner: The Pupil must bend his knees in the first Position, and slide his left Foot to the fifth Position behind; then he must rise upon his Toes with his Knees extended, and walk one Step with his right Foot to the second Position, and another with his left to the fifth Position, and that concludes the right Side-Step.

L: How is the left Side-Step performed?

D: The left Side-Step is composed of a Demiecoupéz forward, and a pà tombéz.

L: Please to explain as intelligibly as you can in what Manner the pà tombéz is performed.

D: As there are four Movements in the two steps that form the Minuet Step, I must join the Demiecoupéz to the pá tombéz, lest I should not be properly understood; but I must observe first that the half coupéz (which is the first Movement of the Minuet-Step) is as long as the three last, one Bar of Minuet-Time for the hall coupéz, and one for the pà tombéz.

L: Pray, Sir, is the Description you have given about the Minuet sufficient for a person to understand the whole?

D: No, Madam, I must explain the Figure; the Graces of the Head, Arms and Body, the manner of giving the right Hand, the left Hand, and likewise both Hands.

L: Well, Sir, explain the figure of the Minuet.

D: I will, Madam, as clear as I possibly can; the form of the figure is this.

[Figure 9 depicting the form of the Minuet figure is inserted here]

And the modern Figure as follows.

Figure 10. The 'Reversed S' form of the Minuet figure, danced with 8 Minuet steps. Page 30.

[Figure 10 depicting the modern form of the Minuet figure is inserted here]

L: But pray, Sir, how do they come to that Figure?

D: After the second Courtesy and Bow in the beginning of the Minuet, the Lady is to do a half coupéz with her right Foot and, pà tombéz; the Gentleman is to do a half coupéz Sideways with his right Foot, and pà de bouréz behind with his left Foot; the Lady must lift up her left Arm in a graceful Manner, the Gentleman must lift up his right Arm: then he must take the Lady's left Hand, and both do a Minuet-Step; then the Gentleman must do right Side-Steps to lead the Lady round, and the Lady forward-steps to go round.

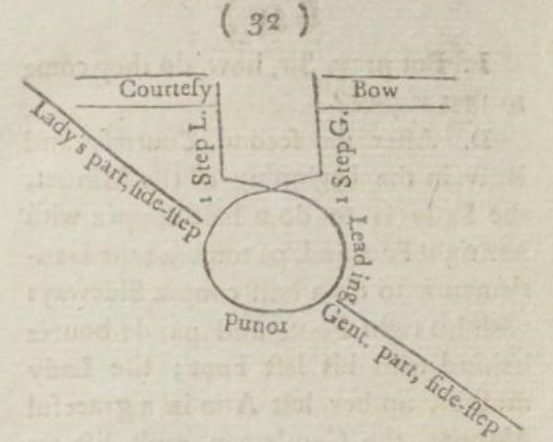

[Figure 11 depicting the parting element is inserted here]

L: Pray, Sir, what do you mean by parting?

D: When the Gentleman looses the Lady's Hand, they part with doing the right Side-Minuet-Step both of them, then they proceed as in the Figure before described.

L: What are the Graces necessary in a Minuet?

D: When the Gentleman leads the Lady round in the beginning of the Minuet, he should have his Face entirely turned towards her, his right Arm must form a Semicircle with his Elbow parallel to his Hand; he must avoid squeezing upon the Lady's Hand with his Thumb, and must lead her round so soft and easy, that she can scarcely perceive he is dancing, though he must perform his right Side-Step, and at the same Time must have an agreeable Smile in his Face, modestly looking at his Partner.

L: Well, Sir, you'll inform me what the Lady is to do I hope.

D: Yes, Madam. The Lady is to lift up her left Arm almost extended, keeping her Elbow up parallel to her Wrist, she must then open her Hand, and let the Gentleman take hold of it, with her Face modestly turned towards him; both the Gentleman and Lady's Arms must be forward, and their Elbows a little bent, the Gentleman's Hand must be under the Lady's.

L: Well, Sir, what follows next, pray?

D: They are to loose Hands, and both perform their right Side-Steps, then they must extend their Arms Side-ways, keeping their Faces towards one another, with their right Shoulders turned contrary to their Faces, and must let their Arms down very slow.

L: What are they to do with their Arms when they have let them down?

D: The Lady is to take her Gown in the same manner as already described, the Gentleman must let his Arms hang by his Sides, and now I will inform you what Use he is to make of them in Dancing. In the first half coupéz of the Minuet-Step, he is to bring his Arms extended but not Stiff, one upon each of his Thighs, he is then to bend his Elbows, inclining them forward; but his Hands must still be kept close to his Thighs, then draw his Arms Sideways, and not turn them back till they are extended; he must count three Crotches of the Music in bringing this Arms forward, and three to bend them, extend them, and let them back; which makes two Bars of Minuet-Time in Music, and one Minuet-Step. When his Arms go back, his Hands must be turned out.

L: Pray, Sir, how many Minuet-Steps must they perform to reach the Corner of the Figure?

D: The Minuet was first composed of two right Side-Steps, two left Side-Steps, and two to cross, but it is frequently danced now with three Steps in each place, if the Room permits it.

L: Well, now for the left Side-Step if you please, Sir.

D: I have already given a Description of the left Side-Step, but I will endeavour to explain the Attitudes of the Head and Arms. In the first half coupéz at the Corner of the Minuet-Figure, the Learners must keep their Faces towards each other in the same manner as the right Side-Step was finished, the half coupéz is to be done forward, and when they bring their left Feet to the second Position (which is called in French dègagé) they must begin to turn their left Shoulders towards the Corner of the Minuet-Figure, and in the pà tombéz (in English the Falling-Step) the Shoulders should be quite turned, their faces towards each other.

L: When are they to give the right Hands?

D: After the Gentleman has led the Lady round, and loos'd her Hand in the beginning of the Minuet, he must dance till it pleases the Lady to offer her right Hand.

L: But suppose the Lady should not be acquainted with this Rule, and should Dance too long.

D: A very long Minuet being tedious to a Company be it danced ever so well, in such a Case the Gentleman must offer his Hand first.

L: Please to inform me the proper Manner the Hands are to be given.

D: At the left Corner of the Minuet-Figure, or a little before they come there, the Lady should begin to lift up her right Arm, but in a very slow Manner, the Arm almost extended, and her Hand opposite her Chin, the Gentleman must do the same, and both do the Minuet Step forward.

L: But I have known Masters who taught a different Step in the places where they give Hands.

D: Yes Madam, it is called a pà grave.

L: And how is that performed?

Figure 11. The parting part of the Minuet figure. Page 32.

D: The Learners must be placed in the third Position, with their right Feet before, then they must bend, rise, and point the right Foot, with the Toe towards the Ground, and slide it to the fourth Position forward, then directly in a supple manner, they must bring their left Feet to the fourth Position forward, and so begin the Minuet-Step forward with their right Feet: but now, if you please, Madam, I'll return to explain the Position of the Arms.

L: Very well, Sir, do so if you please.

D: We left our Dancers with their Arms up, and almost extended doing the Minuet-Step forward; now Madam we must suppose them either to do the pà grave or the plain Minuet-Step, and so proceed to give their right Hands.

L: Well, Sir, please to proceed.

D: When the Dancers approach one another, the Gentleman must bend his Elbow, but at the same Time keep in parallel with his Wrist; then almost extend it to receive the Lady's Hand. The Lady must do the same to give her Hand, the Gentleman must receive it gracefully their Arms forming each of them a Semicircle, they are then to do the Minuet-Step forward, and quite round til they come to the same Place where they took Hands, then they must loose Hands, stretch out their Arms and let them down very slowly, at the same time doing the right Side-Step.

L: Now, Sir, I hope you'll inform me when the left Hand is to be given.

D: Directly when they have reached the right-side Corner of the Minuet-Figure, then with a pà grave (if in Fashion, if not with) a plain Minuet-Step, and the left Hand given in the same manner as already described by the right; they must observe to keep their Faces constantly towards each other.

L: Pray, Sir, when are both Hands to be given?

D: That, Madam, depends upon the Lady the same as giving the right Hand.

L: But please to inform me how they are to be given.

D: In the Beginning of the third left Side-Step at the latter End of the Minuet, the Lady should lift up her Arms in a slow, graceful Manner, the Gentleman perceiving it should do the same, their left Arms being rather more bent than the right. Then each of them must do the Minuet-Step forward, and meet one another in the Form of a Semicircle, and the Side-Steps, Courtesies, and Bows, must be done in the same Manner, as at the beginning of the Minuet.

L: Pray Sir, when the second Courtesy and Bow are ended, what is to be done next?

D: The Gentleman should take the Lady's left Hand with his right, and accompany her to her Place, then make her a Bow, she answers him with a Courtesy, then he retires, and she fits down.

L: What other Dances are there besides the Minuet?

D: The Louvre, the Courente la marriéz, Bretagnie le paspied, Minuet Danjou, Charment, Vainceur, and several others: but none of these graceful Dances are in vogue in England at present, the fashionable Dances chiefly are now the Minuet, le Minuet de la Cour, Cottillions, Quadrilles, and Country-Dances. I must allow the Minuet de la Cour to be a well composed graceful Dance.

L: Can you give me a Description of all the Steps that are made Use of in these Dances.

D: I can, Madam, and if I could not, I should very improperly be called a Dancing-Master.

L: Will you please to satisfy me in this particular?

D: By knowing Corégrafie a good Master can Dance any of these Dances by reading the Paper that contains them.

L: Pray Sir, what do you mean by Corégrafie?

D: It is a method of Writing the Steps for Dancing, something similar to the Notes in Music.

L: Is every Dancing-Master obliged to know Corégrafie?

D: No, Madam, a Number of the capital Masters don't trouble their Heads about it, but I think it proper a Country-Master should know it lest he should be at the Trouble and Expense of going to London to learn every new Dance that comes out.

L: Is Corégrafie easily learnt?

D: Not without a Man is very perfect in the Grounds of Dancing.

Of Stage-Dancing

L: What is Stage-Dancing?

D: Serious-Dancing is the compleatest of all Dancing when well performed.

L: Pray how do you make that appear?

D: This sort of Dancing shews all the Attitudes the human Body is capable of; it discovers the Suppleness, Agility, and Graces of it; it is a Pattern for Princes to go by in Ease and noble Gestures. To see the late Monsieur Dupré unfold his Arms to begin a Dance it was so astonishingly graceful, that a real judge of Dancing would be struck with Admiration. Even the present Monsieur Vestris is admired by all Judges, and he deserves it, for he is certainly an excellent Dancer.

L: But, Sir, you speak so much in favour of this kind of Dancing, and likewise of the Performers, that you make me desirous of having a Description of it?

D: If I was to give a Description of Stage-Dancing it would be tedious, especially as I want to speak of something more useful and necessary for the Advantage of young People in general.

L: What you say, Sir, may be very just, but at the same time some People will be apt to think you are not capable of it.

D: To clear myself from any Suspicion of that Kind, I'll beg Leave to inform you where I've had the Honour of teaching this Kind of Dancing, and likewise some Personages that I have taught. I was first Serious Dancer and Composer of the Stage-Dances at Venice, Mr Murray our English ambassador honoured me with his protection at that Time. From thence I was called to the Duke of Parma's Court where I was three Years in the same Employment: Sir Brooke Bridges Honoured me with his protection at that Time. From thence I was called to Florence where I was three Years first Serious-Dancer, and Composer of Dances, in which town I had the Honour of teaching a number of Noblemen and Ladies (viz): Lord Cowper, Late Lord Northampton, Lord Downe, Sir Brooke Bridges, Mr *Boothby, *Bombry, *Rucher, John White Esq, *Huscher. [*These Gentlemen's Titles I am not acquainted with.] Her Ladyship the Countess Atchaoli, and several others of the first Distinction in that Town; I had the Honour of being protected by Sir Horatio Mann, our Ambassador.

L: Did you ever perform in any other Places?

D: Yes Madam, in other Places of Italy, and at Vienna, the Emperor of Germany's Court, and the last Place I was in abroad was being one of the Dancing Masters of the Royal Academy at Paris.

Of Behaviour

L: Well, enough of this, pray inform me what it is that you think so necessary for young People to know?

D: I mean Behaviour at Table, at Tea, how to meet a Person, and how to part from the Person they meet; the genteel humble Manner of behaving to a Superior, the affable good-natured Manner of behaving to an Inferior, and the observing a polite modest Gesture in all their Actions.

L: Will, in the first place then please to inform them how to behave at Table.

D: When Dinner is upon the Table, the Gentleman (which suppose l am going to instruct) should avoid being in a Hurry to approach it, but rise from his Seat in a calm, modest Manner, and advance towards the Table; the Master or Mistress of the House is to distribute the Places according to the Company, and with Politeness strive to please every Body to their Satisfaction.

L: Suppose an inferior Person should presume to take a Seat before a Person of greater Distinction, and at the same Time place himself above him?

D: The Fault so committed lies entirely in the Pride of the inferior Person, the superior Person will take no Notice of it, it being a breach of Behaviour, but the Company (if polite) will remedy it, by taking a great deal of Notice of the one, and little or none of the other.

L: Should the Mistress of the House always sit at the top of the Table?

D: Being in her own House she has an undoubted Right to it, but if a Person of a much higher Rank should be in Company, it is Politeness in her to offer it, and Politeness in the other to refuse it.

L: Well, Sir, when they are sate down, in what particular Manner are they to behave themselves in regard to Eating and Drinking? for I have seen at some genteel Tables, People that behav'd very vulgarly, such as sitting a great Way from the Table, and it eating Soup holding the Spoon full Handed, and the Hand almost at the Part that goes into the Mouth; others with their Knives and Forks with the Handles upon the Table, and the Blades upright; others taking Meat upon their Plates and putting it in the Dish again; such Behaviour as this is very aukward, and, I hope, you'll explain the true Manner.

D: You may depend upon it Madam, I'll give the best Instruction in my Power, that this vulgar Aukwardness should be avoided.

L: Pray do, Sir.

D: The Person should endeavour to be seated with the Body about three or four Inches from the Table, great Care taken not to touch with his Elbow the Person that sits next him, and at the same Time he must avoid keeping his Elbows too close to his Body. If he is helped to a Plate of Soup, he must let the Servant that brings it put it down before him; then he must avoid spilling, or daubing himself, and take his Spoon up almost at the End with the two fore Fingers and the Thumb of his right Hand, and must mind that he keep the Elbow of his right Arm rather upward, and make as little Noise as he can in sipping up the Soup.

L: Very well, Sir, please to inform them how to make use of their Knives and Forks.

D: The Knife should be made use of with the End of the Handle in the palm of the Hand, and the Fork in the same Manner.

L: How are they to behave when they Drink?

D: Drinking Healths in general is out of Fashion at most genteel Tables, so that the Person that wants Drink must ask the Servant for some, and make Use of it in a graceful Manner without disturbing any one at the Table if he can avoid it.

L: How are they to rise from Table, pray?

D: At a Sovereign's Table, nobody should stir without a great Necessity till the Prince rises himself; then when he goes forward, all his Court follow according to their Ranks.

L: How is it at another Table, pray?

D: A very inferior Person should rise first, and if not desired to sit down again, should make his Obedience, and retire.

L: How should they behave at Tea?

D: By knowing well how to behave at Dinner, a Person cannot misbehave, either at Tea or Supper.

L: Very well, Sir, the next thing I should wish you to speak of, is what Ceremony one Person should use when he meets another.

D: If the Person is just meeting him, he should give the person the Wall if he can, and make a Passing-Bow; if Ladies, Passing-Courtesies.

L: Suppose he has something to say to the Person he meets?

D: Then he must meet him with a straight Bow, and in an affable Manner, address himself.

L: How must he part from the Person when he has finished his Discourse?

D: He must step to the Side he means to go away at, and make a straight Bow.

L: Suppose he lends that Person a Snuff-Box, pray, in what Manner is it to be done with a proper Grace?

D: The Person that gives it must lift up his right Arm, the Elbow level with the Wrist, then draw his Hand towards him a little, and deliver the Box. The Person that receives it, must lift up his Arm (and after he has receiv'd the Box) draw his Hand towards him, in the same Manner as before described.

L: Suppose I present a Fan to a Lady, in what manner am I to do it?

D: The Fan must be held betwixt the two first Fingers and Thumb, the Fingers and Thumb rather bent, the Arm lifted up, and almost extended; you must then bend your Elbow, drawing the Fan towards you, stretch it out again in a soft Manner, and deliver your Fan; the Person that receives it, must take Care not to bend her Elbow till she has the Fan in her Hand, and after she has bent her Elbow, in drawing the Fan towards her, she must drop the Hand that holds the Fan in a graceful Manner upon the other Hand, which should be at the Bottom of her Waist: it must be observed, that in giving or receiving, the Elbow should be kept almost of an equal Height with the Wrist.

L: Suppose a Gentleman meets a very great Person, and has been a Friend of his?

D: He must make an humble Bow, and say nothing.

L: I'm afraid that great Person will think him unmannerly, will he not?

D: No, Madam, it is Manners to avoid being troublesome to any one.

L: Well, but suppose this great Person speaks to him?

D: He must make respectful Answers, and not offer to depart till his Superior goes from him.

L: In what Manner should this Superior behave to him?

D: A real Lady or Gentleman, will always behave with Gentility and Affability.

L: I am very much obliged to you, Sir, for these Instructions, but there is one Thing which I forgot to mention.

D: What's that, Madam?

Of Cotillions, Quadrilles, &c.

L: Please to inform me something concerning the Cotillions, Quadrilles, and Country-Dances?

D: The chief Difficulty in Cotillions is to know the Steps; as to the Figures, they are soon learnt.

L: What are the names of the Steps?

D: The names of the Steps generally made use of in Cotillions are Balancé, Rigodon, Chacéz, Chacézan tournen, Contertamp, Assembléz, Brizéz, Sisolle, Bouréz, Bouréz en boite, &c. &c.

L: Will you please to explain these Steps, Sir?

D: It would be tedious and tiresome to you, Madam for me to explain them all, and swell my Book to too large a Size.

L: What do you mean by Quadrilles?

D: They are Danced the same as the Cotillions, only with this difference, that instead of four Couple in the Cotillions, there are but two in the Quadrilles.

L: What have you to say concerning Country-Dances?

D: Country-Dances are so common with all Ranks of People, that I should think it tedious to you, Madam, to say any Thing concerning them.

L: Pray, Sir, do you teach Country-Dances and Hornpipes?

D: Yes, Madam, when requir'd.

L: Pray, Sir, are the English Country-Dances danced abroad?

D: Yes, Madam, even more than the French Cotillions are danced in England.

L: Pray, Sir, are not the French in general fond of Dancing?

D: No, Madam, some Families do not let their Children dance at all, and I saw a very sorrowful Example of it in Paris. A young lady of Fortune lost both her Parents at Twenty-two years of Age, and finding herself her own Mistress, embraced all Opportunities of introducing herself into all genteel Companies, but in so aukward and pitiful a Manner, that she was generally remarked by the whole Company. One Evening at an Assembly, she was asked to Dance, and not knowing the Consequence of what she was going to do, she was prevailed upon to get up, the Result of which was, she was pushed about in such a Manner in a Cotillion, that she was obliged to sit down again before it was near finished. A petit Maitre and Fortune-seeker perceiving her Confusion, immediately made for the Place where she was sitting, and artfully introducing himself to her as an Admirer, got Leave to see her Home, made her believe he was a Man of great Estate, and offer'd her his Hand in Marriage; the poor innocent Thing swallowed the Bait, and in a short time they were Married, she soon found out to her Sorrow his mean Extraction, and he soon made away with her Fortune, and I am afraid, and have very strong Reasons to think the poor young Lady is now in want of Bread.

L: I am sorry, Sir, for the young Lady's ill Fortune, but this might have happen'd if she had understood Dancing.

D: If she had been instructed in Dancing, this Sharper would not have had so favourable an Opportunity of deceiving her, and the Lady would have been more used to Company in her younger Years, and consequently not so easily imposed upon; so that improving the human Body in Ease, Politeness, Gentility, Grace and Modesty, must be consistent with all good Principles, and will, without doubt, be promoted by all sensible, just and reasonable People; and that encourages me to finish my little Work with this Advice to the Reader.

Advice

- Never boast of your own Politeness: or you become uncivil.

- If you perceive a Person take Liberties with you because you are affable: alter your Behaviour for a Moment, that he may find out his Error.

- If you meet an Acquaintance: strive to be the first in shewing your Civility.

- If an Inferior takes off his Hat to you: return the Compliment, and you'll gain his Affection.

- Never be desirous of shewing your Sense or Talents: or you'll lose the Merit of them.

- Never say I am a Person of high Birth or Education: but shew you are.

- Affability is insinuating: even with Brutes.

- Never be rash in judging others impertinent: it is Ignorance, and their Misfortune.

- Avoid speaking Ill of others: or you'll be suspected yourself.

- Never scorn a Person for his Poverty: it shews Inhumanity and Vulgarity.

- Never be too positive in your own Opinion: it is ungenteel, and seems obstinate.

- Avoid speaking before another Person has finished his Discourse: or you'll be reckon'd unpolite.

- Never praise yourself: for it is weakness.

- Avoid ill Company: if you wish to be well thought of.

- Never neglect a real Friend: it is Ingratitude

- Be not quarrelsome: or you'll be despised

- It is unpolite to make Remarks on another Person's Dress: but observe this Rule,

Do as you'd be done by.

- Never snatch any Thing out of a Person's Hand: it shews ill Breeding.

- The more Modesty you shew: the more you'll be respected and admired, when your Merit is discovered.

- Always speak well of others: and never boast of yourself.

- Be careful in chusing a Friend: the World is deceitful.

- If you find one, be sincere with him, or you'll soon lose him.

- Never give bad Advice intentionally: it is unpardonable.

- Be complaisant: and it will be returned.

- Good Actions are well looked upon: even by ungrateful People, when they reflect upon them.

- Do not be over hasty in believing some great Men's Promises: lest you be deceived.

- Be of no particular Party: and you'll be Friends with all.

- Avoid being desirous of hearing yourself continually Talk: for it is disagreeable to the rest of the Company.

- Remember to be humble and polite to your Superior, meek and affable to your Inferior, think humbly upon what you are, reflect on what you may be, and think charitably of all Mankind.

FINIS.

Conclusion

The Minuet dance of the later 18th century was an important element of the aristocratic dance tradition. Generations of noble born youths had been drilled by their dancing masters in the skills required to cut a fine figure at court. Gardiner's book was likely aimed at a less elite audience, his customers are likely to have been the relatively ordinary people who wanted to better themselves (or their children) for genteel company, perhaps in order to dance the Long Minuet at Bath. At one point he described his work as being to the Advantage of young People in general , the introduction suggests that it might also have been of use to other dancing masters. The Book includes a detailed description of how to dance the Minuet, it's a unique insight into courtly conventions of the period. And yet Gardiner's book was published at a date when the Minuet was losing its prominence, a new generation of young nobility were shunning the Minuet; the corrosive influence of Bunbury's Long Minuet caricature image would go on to be experienced from the following year, it would hasten the decline. The grand balls held in the private homes of the London elite increasingly favoured the simplicity of the Country Dance, the Minuet was relegated almost entirely to the formal Court Balls, it even ceased to be danced there from around the turn of the 19th century.

What we find in Gardiner's text is perhaps the last great insight into the British Minuet dancing tradition before it almost entirely disappeared. It's a fascinating read. We'll end the investigation there, if you have anything further to share about Gardiner or the Minuet traditions of the late 18th Century, do please Contact Us as we'd love to know more.

It seems appropriate to end this paper with Gardiner's 29th and final maxim for the reader from his book: Remember to be humble and polite to your Superior, meek and affable to your Inferior, think humbly upon what you are, reflect on what you may be, and think charitably of all Mankind .

|