|

Paper 63

The Address by Thomas Wilson, 1821

Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor

[Published - 2nd May 2023]

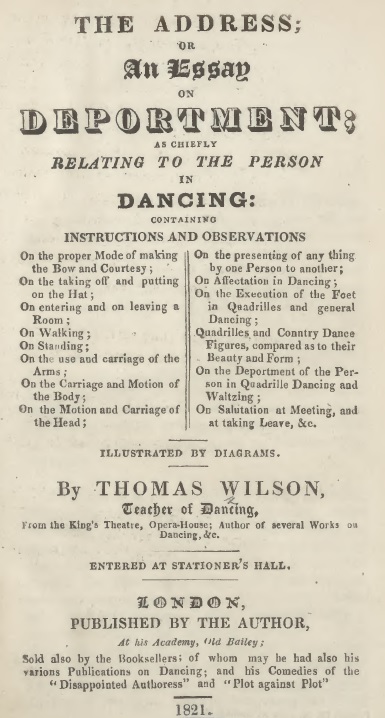

The dancing master Thomas Wilson published a book in 1821 named The Address; or, An Essay on Deportment (see Figure 1). In this paper we provide a transcript of Wilson's book, together with an investigation into the context and background of the work. It's a fascinating text that offers insight into the polite ballroom conventions of the early 19th century, together with advice suitable for the young gentleman or lady entering society.

Wilson didn't provide a table of contents for his book. He did however provide subtitles, the links below can be used to navigate to the parts of Wilson's book that relate to each subject.

Figure 1. Cover of Thomas Wilson's 1821 The Address: Or An Essay on Deportment

Wilson's 1821 book The Address

Thomas Wilson (1774-1854) was the dancing master who, more than any other, documented London's dance practices of the early 19th century. Much of what we know today about Regency era dancing is derived from Wilson's works. We've previously shared a biography of Wilson, you might like to follow the link to read more. Wilson was also a prolific publisher, he issued several major works and numerous minor ones across the 1810s, we've also shared his bibliography of publications in a previous paper. By our date of 1821 Wilson's major works were already published in at least an initial edition, Wilson's attention was beginning to be focussed elsewhere however; he spent much of the early 1820s publishing comic poetry (with little success) and focussing on his dance academies. His 1821 The Address was almost his last significant work from this dance-publishing period of his life; it would only be followed by the second edition of the Quadrille and Cotillion Panorama in 1822 together with a flurry of minor and poetic works including the 1824 second volume of his Danciad (which was both a dance publication and also comic poetry). Two of Wilson's first poetic works were even advertised on the cover of The Address (see Figure 1), they were his 1820 Disappointed Authoress and 1821 Plot against Plot. The Address is therefore interesting as representing one of Wilson's last literary attempts to promote his system of dancing, it was intended to plug one of the remaining gaps in his body of dance literature.

The book's subtitle of An Essay on Deportment as Chiefly Relating to the Person in Dancing reveals the main purpose of the book. Wilson had previously written an Essay on the Deportment of the Person in Country Dancing for his 1820 Complete System of English Country Dancing, this may have been inspired him to undertake a more complete investigation of the subject. Almost every point made in the essay would go on to reappear in The Address, usually in a fuller form with further commentary added. The initial essay was just five pages long, whereas The Address was around thirty pages long with additional supporting matter such as illustrations, a preface and advertisements. The price at which The Address was sold is not entirely clear; an anecdote within the preface suggests that it was priced at less than one twentieth part of the usual charge of the teacher , a sum he'd defined as being three to five guineas , thereby implying that the price tag for The Address was somewhere between three and five shillings (there being 21 shillings in a guinea). The price of his book was therefore, according to Wilson, excellent value compared to paying a tutor to be taught the same things. Whereas purchasing Wilson's Complete System of English Country Dancing would have cost 10 shillings and 6 pence, it was a much longer work.

The book was probably being written in early 1821 and was likely published in either late May or early June of 1821. We can be reasonably confident about this as Wilson explicitly dated his preface to the 9th April 1821, the image plates within the book are also dated to the 15th April 1821. Whereas a review of the book was published in the June 1821 edition of The New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal so it was evidently available for purchase by then. The content of the book would have been relevant to London's ballrooms at the date of publication, so too for most of the preceding twenty or so years. Wilson wasn't documenting a recent change in the prevailing ballroom conventions of 1821, he was instead investigating the general trends of elite ballroom dancing across the early 19th century. Modern readers will find it relevant to most modern discussions relating to Regency dancing (for whatever time-frame of Regency one prefers to use).

Wilson's The Address is largely unknown today, very few copies are known to be extant compared to his more significant works. It's likely that it only saw a single edition and was not subsequently reissued. It is nonetheless fascinating from a modern point of view, it offers insight into the what the mind of a dancing master of the early 1820s thought to be important in social dancing, especially with respect to deportment and elegance.

A full transcript of the work is included below, first we'll investigate a little more about the context of the work, including the vexing question of what precisely the term The Address actually meant.

Defining The Address , as taught by a dancing master

Dancing masters (and other teachers of good manners) had probably used the phrase The Address throughout the 18th century to describe the manner in which a graceful and polite person would courteously interact with their peers. It is somewhat archaic today of course, a modern reader is unlikely to be familiar with the term. Two hundred years ago it implied more than just a knowledge of how to address someone, it rather implied how to move gracefully and politely while addressing someone. Samuel Johnson's dictionary of 1755 offered several different definitions for the word address . In addition to what, for us, would be the common meanings it also implied the Manner of addressing another in the sense of a man of a pleasing address . Jarvis's 1793 Dictionary of the English Language offered a further definition as to prepare one's self for any action and even a mode of behaviour . The phrase The Address is of uncertain antiquity but the associated skills were certainly taught by dancing masters across the 18th century. The Online Etymolgy Dictionary suggests that the word address used in the sense of dutiful or courteous approach goes as far back as the 1530s.

Someone learning The Address would be taught how to enter or leave a room politely, to put on or take off their hat, to make a bow or courtsy, even how to hand an item to another person. The Address was part of how individuals should deport themselves, it was part of the study of deportment . These skills could also be relevant in dancing, especially in Minuet dancing, hence the expectation of learning the skills from a dancing master in preparation for dancing a minuet in the ballroom. Giovanni-Andrea Gallini (later Sir John Gallini) in his 1772 Treatise on the Art of Dancing wrote of the Minuet dance that besides the effect of the moment in pleasing the spectators; the being well versed in this dance especially contributes greatly to form the gait, and address, as well as the manner in which we should present ourselves. It has a sensible influence in the polishing and fashioning the air and deportment in all occasions of appearence in life. It helps to wear off anything of clownishness in the carriage of the person, and breathes itself into otherwise the most indifferent actions, in a genteel and agreeable manner of performing them . The grace of the Minuet dance and the genteel manner of the courtier were linked, an 18th century dancing master would teach both.

By the early 19th century the Minuet dance had fallen from favour and was rarely being performed socially. Dancing Masters continued to find skill in the Minuet to be a useful accomplishment for the dancer however. F. J. Lambert in his 1815 Treatise on Dancing wrote: What is more striking than to see persons walk well, and acquit themselves genteely? Polite manners and good address, shew at once good breeding and the habit of keeping good company, and fail not to command the attention and respect of others. . Lambert's book went on to describe how to dance a minuet. Thomas Wilson, in the introduction to his 1821 The Address explained that many dancing masters, where they were qualified to do so, charged an excessive amount to teach The Address ; he suggested that purchasing his book would be a more cost effective alternative option. Of course he was not the first to have offered such advice in print.

A particularly lengthy guide to genteel behaviour was written by Matthew Towle for his 1770 Young Gentleman and Lady's Private Tutor (see Figure 2). The third part of this work related to Behaviour in the Dancing School, it included rules and directions for Dancing a Minuet, genteel Standing, Walking, Giving, Receiving, Bowing, and to make a Curt'sie, at coming in or going out of a Room . Towle's book aimed to promote a genteel behaviour and polite address , he considered the polite accomplishments to be part of the tuition one might receive for dancing the Minuet. S. J. Gardiner in his 1786 A Definition of Minuet-Dancing also included advice covering social interaction, his book referred to table manners, the passing of objects between people and how to bow or curtsy politely. Once again the advice was considered appropriate to be combined with a guide to dancing the Minuet. Further such examples can be found. Wilson's The Address, published as it was in 1821, did not include any advice for dancing the old-fasioned Minuet dance, it did however cover the polite manners otherwise considered to be part of The Address .

Some commentators likened the disciplines taught as part of The Address to the French concept of Savoir Vivre , a term that implies familiarity with the customs of polite society. For example, John Andrews's 1785 A Comparative View of the French and English Nations opined: To make a bow, enter a room, or offer any thing gracefully; to accost a lady, or run over the alphabet of compliments, with an air of facility, and without the least appearance of bashfulness or inexperience, is savoir vivre . . The list of accomplishments closely matches those of The Address .

What dancing masters would teach as part of The Address could vary, it generally included how to enter or leave a room, bow or curtsy, put on or take off a hat, and hand something to another person; these were genteel accomplishments and manners that would prepare the student for polite society.

Was Wilson qualified to teach The Address ?

Figure 3. Advertisements by Mr Harpham in the Leeds Intelligencer for the 2nd of April 1804 (above) and Mr Simmonds in the Sheffield Independent for the 1st of November 1823 (below). Both reference tuition in deportment. Images © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD and reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive.

The question might be asked of how qualified Wilson himself was to actually teach The Address . He presented himself as being an expert and his observations as being correct; yet from the point of view of a modern commentator, was Wilson correctly documenting the elements of genteel behaviour of his own day?

The Address was associated with the polite behaviour of the aristocracy and court. It was something that the aristocracy of the mid 18th century genuinely did consider to be of importance. For example, a collection of Letters Written by the Late Right Honourable Philip Dormer Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield, to His Son were published in 1774; in a letter dated November 19th 1745 Stanhope wrote: Now that the Christmas breaking up draws near, I have ordered Mr Desnoyers to go to you, during that time, to teach you to dance. I desire you will particularly attend to the graceful motion of your arms; which, with the manner of putting on your hat, and giving your hand, is all that a gentleman need attend to. Dancing is in itself a very trifling, silly thing; but it is one of those established follies to which people of sense are sometimes obliged to conform; and then they should be able to do it well. And, though I would not have you a dancer, yet, when you do dance, I would have you dance well, as I would have you do every thing, you do, well. There is no one thing so trifling, but which (if it is to be done at all) ought to be done well. . If the Earl of Chesterfield thought that dancing was important, and that the method of putting on of a hat and presenting a hand was especially important, it's reasonable to imagine that was also an opinion generally held by his peers. Stanhope had hired George Desnoyer, one of London's most celebrated dancing masters, to teach his son personally. Desnoyer had also been, at around this time, dancing master to the future King George III. A master like George Desnoyer could not only teach The Address, he might even influence it, perhaps encouraging embellishments that he personally considered to be of genteel character. Wilson referenced this letter of Stanhope's within his book as an example of the importance of learning The Address .

An elite dancing master like George Desnoyer or Giovanni Gallini might teach the upper echelons of the aristocracy to dance, an accomplished master such as Matthew Towle or S. J. Gardiner might teach at a slightly lower rung of the social ladder. But what of Thomas Wilson around the start of the 19th century? Wilson was certainly an accomplished dancer and a successful tutor, but who were his clients? Did he directly interact with the aristocracy and nobility? Wilson was a prolific advertiser in the London newspapers, many of his students are likely to have found him through those same newspapers. I suspect that most of his pupils were the children of the professional classes, their parents would aspire for something greater and might respond to advertisements in the press. There can be little doubt that some high-society gentlemen would attend his public balls, I've little evidence of Wilson's actually teaching them to dance though (unlike his contemporaries George Jenkins and Edward Payne who certainly did teach members of the nobility to dance). Given Wilson's clientele, was he in a position to know what he was talking about when it came to genteel behaviour in private parlours and The Address ?

We can only speculate as to an answer. My suspicion is that Wilson's primary source of information was the various etiquette guides published in the 18th century by the likes of Matthew Towle and S. J. Gardiner. My guess is that he absorbed their information and rewrote some of the same ideas in his own words and for his own audience. His customers were not (in general) the aristocracy, rather they were people who hoped to better themselves by learning to behave like the nobility and gentry. That's not to suggest that Wilson was wrong in anything that he wrote, just that he may have cultivated the impression of being better connected than in fact he was. The genteel advice he offered could easily have been acquired from the contents of his own personal library. Wilson's advice may have been a little anachronistic, perhaps focussing on courtly behaviour of the later 18th century rather than that of his own day, it was likely close enough to reality to be useful though.

Wilson wouldn't have been alone in teaching something over which he was not directly informed. Dancing Masters around the country did likewise. Figure 3 shows two advertisements issued by provincial Dancing Masters offering tuition in Deportment , the first from 1804 and the second from 1823. The tuition offered in each case was likely learned either from reading etiquette guides or from the dancing master's own tutor, rather than from a direct knowledge of courtly conventions. Provincial dancing masters often travelled to London to refresh their knowledge of the latest trends in dancing, tuition in deportment might perhaps have been renewed at the same time. It was to masters like Thomas Wilson or G.M.S. Chivers that the provincial dance masters might apply, quite where these London dancing masters received their information is less certain. Chivers and Wilson were rivals, Chivers also advertised tuition in The Address ; an advertisement within his own 1821 Dancer's Guide mentioned that he tenders his services for the Instruction of Youth, of either Sex, in that essential accomplishment - the Polite Art of Dancing . The Address and Deportment is attended to, particularly to form them for the most fashionable circles . It's possible that Wilson was partially inspired to write his book in response to Chivers openly offering tuition in The Address .

It should also be acknowledged that much of the content of Wilson's The Address is not derived from the pages of the 18th century etiquette guides. Some of the text relates to issues that Wilson personally cared about, examples include lists of serpentine (and therefore beautiful) dance figures, deportment of the person within a dance and concerns around affectation in dancing. Although part of the text may have been inspired by Wilson's 18th century predecessors, much of it was very much his own. In so far as Wilson's observations relate to the ballroom of his own day, that was Wilson's specialist subject; his observations were undoubtedly what he himself taught to his own students and encouraged at the Public Balls that he facilitated. The modern day Regency Dancer seeking to recreate the elegance of a Regency era ballroom would do well to consider Wilson's advice.

Observations related to Wilson's Book The Address

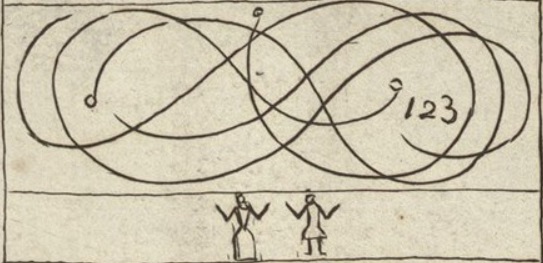

Wilson will have had many sources to draw upon when writing his book. One of them is readily identified: William Hogarth's 1753 work The Analysis of Beauty. Wilson alludes to it indirectly. One of Hogarth's main ideas was that a serpentine or S-shaped curve is fundamental to beauty; he went on to explain how the Minuet dance embodies this natural beauty and offered the Hey figure in Country Dancing as being similarly evocative (see Figure 4). Wilson took this observation regarding the Hey as his starting point for defining that which is beautiful in ballroom dancing. Wilson didn't actually name Hogarth within his work, his familiarity with Hogarth's text is clear however, perhaps most so with this sentence: With persons of taste, and true judges of beauty, the gently flowing Serpentine and Curved Lines, form the acme of grace, and have always been considered most beautiful. , a line that neatly summarises much of Hogarth's work. Wilson wrote very little on the subject of the Minuet dance within his book, the exception being a suggestion that Shakespeare might have had the Minuet in mind when writing a line of dialogue in his Winter's Tale; this suggestion is almost certainly derived from Hogarth's Analysis of Beauty where the same observation is made.

Figure 4. Hogarth's depiction of a Hey figure from Country Dancing in his 1753 The Analysis of Beauty.

Having defined the Hey figure as being fundamentally beautiful, Wilson went on to identify other figures that are similar in nature to the hey . Wilson liked producing lists of country dancing figures. In several of his previous works he produced such lists; he grouped figures based on their attributes, including their length, whether progressive, whether performed from the top of a minor set, whether they terminate proper and so forth. Wilson probably enjoyed creating a new list of figures for The Address based on how curvy or angular they were. The curved figures are said to be the most beautiful, the angular figures the least so. Wilson implied that if one were designing a dance one could deliberately feature only the most beautiful of figures. I'm not aware of any previous writer on etiquette and deportment having listed dance figures in this way, Wilson had taken Hogarth's concept and developed it according to his own unique motivations.

Wilson, in The Address, also modernised his discussion on deportment (compared to the 18th century writers) by referencing the modern dance styles of the later 1810s, specifically the Quadrille and the Waltz dances. The previous writers had focussed on the Minuet dance. And yet the observations that Wilson shared don't offer a great deal of new insight, he instead accused dancers of being inelegant in their movements and lacking the most basic knowledge of figures and steps. He suggested that they should attend his in-person academies or read his other books to learn more. Similarly shallow observations can be found across the work; he repeatedly pointed out common mistakes and invited the reader to buy his other books in order to correct them. Anyone who purchased The Address may have found this frustrating. His reviewers certainly did. A review published in The New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal for June 1821 records: we found our eyes continually wandering from the text to the references in the marginal notes, See my Complete System of English Country Dancing , See my Quadrille Panorama, See my Companion to the Ball-Room, See my Correct Method of German and French Waltzing, &c. &c. informed us of fresh attainments to be made, of graces still more graceful, and figures still more figurative, we laid the performance down in despair, though not with out the profoundest admiration of Mr Wilson's generosity, in thus imparting to the public for a few shillings, those arts and mysteries of address, for teaching which he informs us other professors less disinterested than himself, invariably charge from three to five guineas. Wilson wrote relatively little about the characteristics of a perfect performance in dance, he wrote rather more concerning what to avoid.

A few of Wilson's more practical and stylistic observations may be of particular interest to modern Regency Dance enthusiasts. For example, he commented on how a bow or curtsy might be needed within a Country Dance should the music briefly pause, or how inactive dancers should stand. When an arm is presented in a dance it should form a gentle curve, it should not be raised above the height of the shoulder. When leading down the middle is performed the arms should not bounce up and down. A suitable distance should be kept between dancers so that swinging and turning figures can be performed without bending of the elbows. The palms of the hands should never be turned upwards. When joining hands with a partner one should only use the forefinger and thumb to do so, the entire hand should not be grasped. Wilson's references to steps were more concerned about timing within a figure (so as to avoid dancers colliding) than about the use of specific named steps. These are stylistic comments that aren't entirely obvious to the modern enthusist, they're part of how a regency era dancing master would have wanted his pupils to dance. We've written more about stylistic embellishments for Country Dancing in a previous paper.

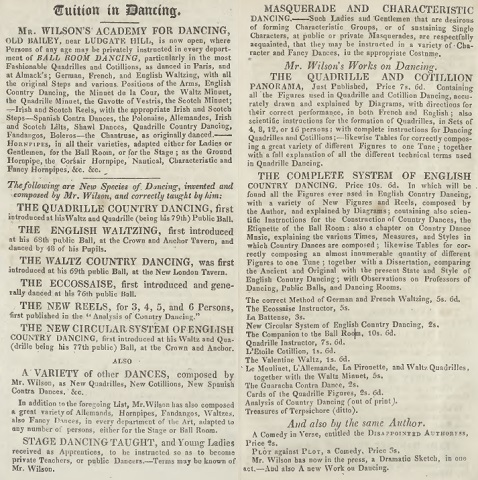

Figure 5. Wilson's advertisement of Tuition in Dancing at the back of The Address.

Much of what I find fascinating about The Address is what isn't said. There are elements of the modern experience of Regency Dancing that we might have expected Wilson to have commented upon, though he did not do so. Subjects like the importance of giving weight in a turn, the direction of movement in a circle, the selection of steps to use for a dance, whether inactive dancers should join hands when progressing up a country dance, who's hand goes above in a Hands Across figure, and so forth. Hundreds of questions might be asked in a modern context about the historical experience, many of them couldn't be answered from reading this book (or from reading Wilson's other books). This implies a fascinating dissonance between the mind of Thomas Wilson two hundred or so years ago (with the issues that he considered to be important), and the mind of a modern enthusiast who expects there to be a universally correct answer for every possible stylistic question. The modern enthusiast expects certainty, whereas Wilson might never have imagined such questions being asked. Part of the problem is that the common experience two hundred years ago was so universal and ubiquitous that nobody felt the need to record it in print, modern assumptions about historical dancing may (or may not) be correct. For example, I have found nothing in Wilson's books to suggest that everybody in a Country Dance would be using the same dancing steps at the same time, whereas the modern dancer will tend to assume that they should. A modern caller might even announce that a dance should be performed in a particular step. Nor have I found anything in Wilson's books to suggest that perfect synchronisation of movement was expected from the dancers; they were expected to end each figure in the right place and at the right time, but little beyond that. The modern experience of treating historical social dance as a performance, perfected for the movie screen, can mislead us in our expectations. Wilson's book addressed many of the real issues that he was concerned about in the early 1820s, both the topics that he wrote about, and the topics he did not write about, are of great interest and offer insight into the genuine experience of social dancers at that time.

Two final pages of particular interest are not technically part of the book at all. They're an advertisement that Wilson had bound into the back of the book (see Figure 5). This text is relatively biographical and offers a hint of insight into Wilson's life and work. He began by alerting the reader to the existence of his academy and the many types of dancing that he could teach there. He also noted six types of dance that he had personally invented. He offered a variety of other new dances, tuition in stage dancing and coaching in masquerade and character dancing. Then he offered a list of his works that were available for sale, including some minor works that are no longer known to be extant. It's a treasure trove of details, you can read more in our papers on Wilson's biography and bibliography.

Of all the advice and warnings that Wilson offered, the statement I like best reads: all persons standing up in a Dance are alike entitled to civil and polite attention. This statement appears in a section on affectation in dancing, it follows the observation that some excellent dancers might look down upon the efforts of others. This is not acceptable, the best dancers are those who dance with the company, not those who consider themselves superior to the company. This is a slogan that all dancers would do well to adopt!

Comments on the Transcription

There is a copy of The Address available to study online courtesy of the National Library of Scotland. They own one of the few extant copies still known to exist. It seems likely that few copies were ever printed and sold, it wasn't one of Wilson's more popular works. The NLS trialled a scheme a few years ago where the public could pay for a digitised scan to be produced of a work from their special collections, they would then make the resultant files publicly available for download from their website. I took the opportunity to commission a scan of this book at that time, they went on to share it as promised. Their scan is of a very high quality, their associated transcript is almost perfect; I've only made modest corrections over their version of the text for the new transcript provided below. Readers may prefer to use their digitised copy in preference to the transcript provided here.

The text provided below is a faithful transcript of the original work. Minor corrections are introduced for formatting purposes such as recombining words that were split across lines in the original. Footnotes are collected at the end of the section to which they apply. References to Wilson's other books have been converted to links where appropriate. Images have been moved from their original place in the book to locations closer to where they are referenced, Wilson's references to them are normalised and updated accordingly. A leading and trailing ellipsis has been added where a paragraph of text is split across two pages, any text in square brackets has been added to demarcate the page numbers and to provide similar typographical commentary.

What follows is a full transcript of Wilson's The Address.

The Transcription

[page 1]

[Cover, see Figure 1]

[page 2]

[blank]

[page 3]

Preface

A professional practice, as teacher of Dancing, for more than twenty years, has given me an intercourse with persons of all ages and classes of society, that has furnished me with the means of knowing the general deficiency in the most essential mode of Address and requisite Deportment, both in and without the Ball Room. Having found that many of my pupils, although they had acquired an excellent scholastic education, were yet wholly unacquainted with these established rules of politeness, I have been induced to publish this little Work, in which will be found such instructions, as with the aid of the accompanying Diagrams, will, it is hoped, enable the student to acquire those qualifications so indispensably requisite.

Although it is the province of every Dancing Master to teach these accomplishments, when required, yet there are to be found many as destitute of these requisites as the generality of their pupils, and who think nothing more is wanted than a few figures and steps; and those teachers who are thoroughly qualified to give instructions, when required to impart them, generally make a separate charge for what is termed, The Address, and that only consists of instructions for making the Bow and the Courtesy, the entering and leaving a Room, the putting on and taking off the Hat, and the presenting any thing...

[page 4]

... by one person to another. This portion of Deportment is all that is included in what is termed The Address, and for this, when taught separately, eminent teachers never charge less than from three to five guineas. Now, as the whole of this is correctly laid down with other necessary information in Deportment, at less than one twentieth part of the usual charge of the teacher, it is obvious that the price of this Work is very low, in proportion to its usefulness; it is presumed also, that it may not be useless even to those who chuse to receive personal instruction from a teacher, as they may be enabled satisfactorily to know to what points such instructions should extend, and whether justice is done to them by their masters.

THOMAS WILSON

Old Bailey, 9th April 1821.

[page 5]

The Address; or, An Essay on Deportment

On the Deportment of the Person

A graceful and easy Deportment, is not only an essential and necessary acquirement, as relative to the ball room, but its attainment will be found requisite and highly useful in the general carriage and movements of the figure. Indeed, the study and practice of a general good deportment, will have the effect of removing even natural deformity, in many instances, and will give that simplicity and ease in the general use of the limbs, that produces a beautiful and strikingly pleasing effect.

That a graceful deportment of the person is useful, may be learnt from the writings of men of polite literature of all countries and ages; all of whom have agreed, that a graceful and easy deportment of the person, added to polite conversation, will prove of more real value to its possessors in their general intercourse with the world, than all the learning studiously acquired without it.

[page 6]

The great Duke of Marlborough (who had not the character of a learned man) was enabled, through the possession of these qualifications, independent of his skill as a general, to become so successful as a negociator; and so well was the governing influence over the minds of others known to the celebrated Earl of Chesterfield, that in his Letters to his Son, he was ever reminding him of the necessity of paying attention to the graces, and of acquiring an easy deportment; and recommended certain masters, to teach what his Lordship considered the most useful accomplishment.

Numerous instances might be quoted, shewing the necessity for its acquirement; but it is generally known, that a genteel address and easy deportment, without any other recommendation, have laid the foundation of the future fortunes of many persons: while others, possessing great mental abilities, perhaps, but for the want of a proper attention to deportment, have contracted rude and clownish habits, and thereby obstructed the road that might otherwise have led to their preferment.

It is generally remarked, that much depends on first impressions, from which the necessity is obvious, that all persons, considering their own interest, should so qualify themselves, as to become acquainted with every possible acquirement, fitted to prevent any evil prejudices that might otherwise arise and be entertained.

In the ball room, or in any other assembly, the visitors generally form new acquaintances, who are chosen from their appearance and deportment; consequently, attention to a refined mode of deportment must form the best means of recommendation.

Many persons of intrinsic worth, possessing great talent and amiable dispositions, are passed...

[page 7]

...unnoticed in the ball room, in consequence of their awkward deportment. The value of such persons acquaintance, and all the benefits arising from their superior knowledge, are thereby lost; but which might otherwise prove of infinite service to those possessing acquirements of less real value, yet, with a more polished and easy exterior, which they are enabled to assume, from proper attention to good instruction in the deportment of their persons. The question naturally arises, how is it to be accounted for, that persons with judgment and genius, and acquirements arising from the application of both, should not see the necessity of learning this essential part of polite education.

The study of Deportment furnishes an ease and grace to every action adapted to its peculiar use and intention. It is not, as is very frequently and most erroneously held out, acquired in the learning of Dancing; (notwithstanding, it cannot be denied to be the province of every teacher of that art, to give to the pupil the necessary instructions for deportment of the person, generally, as in walking, standing, &c.;) but the proper mode of taking off and putting on the hat, presenting any article, as a glove, snuff box, card, &c. &c.; situations in which persons may be placed, and offices that they may have to perform, that may never occur in dancing, or in the ball room, are altogether totally neglected.

The modern ball room is miserably deficient in the display of graceful deportment; so many in the first place having received no instruction in dancing, conceive that a slight knowledge of figures, and a shuffling about of the feet, form the whole of what is required; and, in the next place, most of those who may have received...

[page 8]

...instructions, have been either very insufficiently taught, or have been very inattentive.

Many modern teachers are totally ignorant of the correct rules essentially necessary to the acquirement of a graceful deportment; but the teachers of the old school, having a thorough knowledge of these requisites, invariably teach Deportment, not as exclusively to be observed in the ball room, but to give their pupils such instructions as constitute a certain foundation for their correct and general observance.

A perfect knowledge of Figures and Steps is not alone sufficient to form the dancer; a study of the use of the head, arms, and body, as applying to and accompanying each varied movement, is indispensably necessary to be attained, before the required effect can be produced - even by those capable of the most brilliant execution with the feet.

Those persons, therefore, who are anxious to become possessed of so useful and pleasing an accomplishment as dancing, and to excel in the ball room, will find a close attention to the study of a graceful deportment of the greatest possible advantage. It will, in the study of it, require all the attention that can be paid; not being so mechanically acquired as Figures and Steps, but requiring not only much practice, but nicety of observation, previous to that ease being obtained, which produces the ultimate effect of pleasing simplicity and beauty - never failing to attract the eye of taste, and ever exciting more attention and admiration, than a brilliant execution of the feet alone is capable of.

When the student becomes well grounded in the correct principles, he will find that they consist of but few; and he will be enabled to divide and display the various ornamental parts forming...

[page 9]

...a graceful deportment at pleasure, according to different situations.

The student's first object, however, must be an attainment of the Figures and Steps ; and he must be enabled with ease and precision, to adapt them properly to music, previous to the study of the rules of deportment, required in dancing. The figures, steps, and music, form the structure; and a graceful deportment embellishes, ornaments, and harmonizes the whole.

This article was intended principally for the use of those frequenting the ball room; yet,

several of the remarks and instructions may be properly applied, and of utility out of the ball room. Such others are added as will assist greatly towards the acquirement of an easy deportment, by those persons unacquainted with dancing, who, though not inclined to attain that accomplishment, may be anxious to acquire an easy and genteel deportment; conceiving it indispensably necessary to the attainment of the objects they may have in view, in their commerce with the world. That it is generally necessary is universally admitted, as it draws the distinction between the accomplished and the uncultivated.

By means of the few sketches referred to, and illustrative of this article, the student will be assisted in acquiring a graceful and easy deportment; and, added to the following rules, with the aid of a good teacher, persons of the most ordinary capacity may be enabled to acquire what is necessary for its attainment - the sketches and rules given will no doubt of themselves prove fully sufficient.

In laying down rules for the attainment of a graceful deportment, some idea becomes necessary to be given, of the received opinions concerning beauty and deformity, and the sort...

[page 10]

...of forms and lines that contribute to either, that the student may know in detail the figures, lines, and forms, held as the most beautiful, by persons of taste, and judges of that in which beauty and deformity consist.

It would not be sufficient to declaim against existing errors, and a rude uncultivated manner, without pointing out in what they consist, and shewing the means and necessity for their removal and improvement. The following remarks, observations, and rules, are therefore given; and which it is trusted will tend to realize so desirable and necessary an object.

Country Dance and Quadrille Figures Compared With Each Other, as to their Beauty of Form

To enable the learner, or the dancer, to select such figures in the setting of a dance as will produce the most beautiful and pleasing effects, it will be proper, in the first place, to point out the most elegant, as far as relates to their various movements; and by contrasting them with each other, shew in what consists their beauty.

The Diagrams will shew, that the Figures in Country Dancing and Quadrilles consist, and partake of various forms and directions of lines, traced in their performance; as circular, half circular, curved, serpentine, angular, and straight lines.*

[page 11]

The figures or forms, consisting of serpentine lines, are esteemed the most beautiful.

The figure Hey in Country Dancing, being composed of several of those lines interlacing and intervolving each other, claims the pre-eminence, by reason of the flowing graces and beauty it necessarily displays in its performance.

Whole Figure at Top, assimilates to the beauty of the figure Hey, and resembles in its performance the figure of 8.

Swing Corners is a figure, that, being composed of serpentine and half circular movements, has, when well performed, a very pleasing effect.

Turn Corners, partaking more of half circular and less of serpentine lines, is not so beautiful a figure as the last; but still pleasing. The Quadrille Figure, Chaine des Dames, has a pleasing effect - resembling the Country Dance Figure, Swing Corners, being composed of serpentine lines.

Circular and Half Circular Movements, of which there are many in Country Dancing and Quadrilles, as Hands Round, Hands Across, Moulinet, Tours de Main, Turn your Partner, are agreeable; though not so pleasing as the Serpentine Movement. The last figures have a very good effect when well performed, and the couples stand at a proper distance, and partners immediately opposite to each other, in Country Dancing, and in their proper situations in Quadrilles; yet it has not the advantage, in...

[page 12]

...its performance, of interlacing three serpentine lines within each other, and traced in different directions, as in the Hey.

The Country Dance Figures, Swing with the Right Hands, top and bottom, and Swing with the Right Hand round the Second Couple, and then with the Left, and the Quadrille Figure, La Grande Chaine, partly composed of the serpentine form, have always a good effect, and accord pleasingly with true taste, when correctly performed.

The foregoing are the principal Figures, considered the most beautiful in form and construction.

All Figures composed of straight and angular forms, of which there are several in Country

Dancing and Quadrilles, have a different effect, and serve to vary the form of the dance, by setting off to greater advantage those before mentioned.

* The whole of the various forms and evolutions of all the Country Dance Figures, are correctly drawn and explained by means of Diagrams in my Complete System of English Country Dancing. For a correct idea of the form and construction of Quadrille Figures, see my Quadrille Panorama, in which all the various forms are also described by Diagrams.

In Country Dances

Lead down the Middle, and up again, though it is a Figure frequently performed, excites but little attention.

Lead Outsides, or what ought more properly to be called Lead to Outsides, is also composed of straight lines; and a variety of other figures, although very useful in assisting to form the dance, and almost constantly introduced, produce nothing pleasing either to the performer or spectator.

Angular Movements, by a single person, are not calculated to please either in Country Dancing, or in any other case, being the very reverse of graceful and beautiful forms.

[page 13]

The Figure of Right Angles, Top and Bottom *, affords a specimen.

* See the form of this Figure in System of English Country Dancing, page 122.

Quadrille Figures

The Quadrille Figures, En avant, En arriere, Chassez a droite, & A gauche, being likewise composed of straight lines, have a similar effect.

Also the Quadrille Figure L'Eté *, which is a rectangular form.

But the Grand Quarrée, in Quadrille Dancing, though composed of Angular Movements; yet (as they intersect each other) when well performed, has an interesting effect.

From the preceding remarks, the dancer will be enabled to judge of the effect capable of being produced by the combination of different Figures, according to their forms, and have, in the selection of them, in forming or setting Country Dances, or composing Quadrilles, an opportunity of suiting taste in various forms.

* See Quadrille Panorama, for the correct form of these Figures.

The Effect of Straight Lines

Straight Lines are useful, but not elegant; and, when applied to the Human Figure, are productive of an extremely ungraceful effect.

[page 14]

Straight and Angular Lines applied to and produced in laborious and violent motion, are more mechanical, and consequently more easily imitated, by the means of mechanism. Puppets may be made to move with an agility the Human Figure is incapable of; yet the means cannot be given them of displaying those graceful, easy, and pleasing movements, of which animated nature is exclusively in possession.

The uninteresting sameness produced by straight lines is exemplified in the marching of soldiers, which, from being so truly mechanical, becomes so easy of imitation, that a fac simile is capable of being represented on the top of a clock, &c.

The Effect of Serpentine or Curved Lines

With persons of taste, and true judges of beauty, the gently flowing Serpentine and Curved Lines, form the acme of grace, and have always been considered most beautiful.

It is in animated nature that these lines and forms predominate, and insure to themselves, in the judgment of all, that pre-eminence, which from their beauty and grace they justly claim.

That part of the Creation which is the most beautiful in form, is capable of displaying the most beautiful motions. For instance, the swan has been ever accounted one of the most beautiful birds in the Creation; and, when seen gently gliding along the chrystal stream, the elegant serpentine and gracefully varied movement of its neck, never fails to excite admiration.

[page 15]

It is not the form alone that strikes us as being beautiful; but the idea coupled with it, that that form is capable of producing so many varied and equally beautiful gestures.

In the species of horses, that is said to be the most beautiful, the neck from its length is capable of the greatest variety of graceful movements.

The Minuet

The Minuet, from its gentle and gracefully rising and sinking movements, may be deemed a model of graceful beauty in Dancing, when well performed; it is probable that the Minuet was alluded to by Shakespeare, in his Winter's Tale, when Perdita says, When you dance, I wish you a wave of the sea.

The Effect of Circular Lines and Movements

Circular Lines, Forms, or Movements, though not so beautiful and elegant in their formation or effect, as serpentine lines, yet are of such a pleasing nature, as to claim the attention, and attract the particular notice of the spectators.

The dancers, in performing these Movements, have ample opportunity afforded them of displaying their personal accomplishments. The figures of Hands Six Round, Hands Across, in Country Dancing; also Le Grand Rond, in Quadrilles, requiring several persons in their performance, the circular display of the figures...

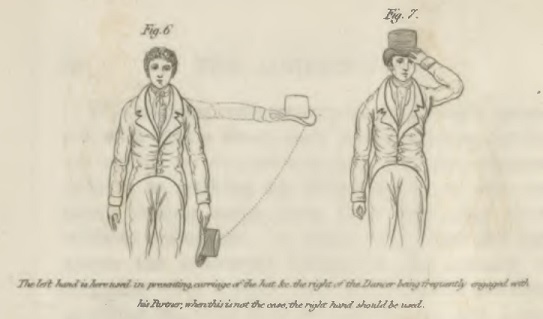

Figure 6. The Address Plate 1 Figures 1 & 2

[page 16]

...and forms of the different Dancers, produces much pleasing variety and effect. A proportionate effect is produced in the performance of half circular movements, according to the extent, situation, and number of persons employed in their performance.

The foregoing remarks being deemed sufficient to enable the dancer to form an idea of those figures and forms esteemed the most beautiful, and to assist him in the composition and performance of such dances, as cannot fail to attract and merit admiration; an attention will, in the next place, be necessary to the following observations and instructions, which not only relate to such particulars as are absolutely requisite to be descanted on, to point out the bad habits contracted and continued to be practised, in defiance of the rules of grace, both within and without the ball room; but also to afford a stimulus and facility to improvement.

Figure 7. The Address Plate 1 Figure 3

Bows and Courtesies

Form the grand feature of deportment - they are material requisites in polite life; and it is indispensably necessary that they should be made in a graceful, easy manner, that the lady and gentleman may be distinguished from the rude, uneducated, and vulgar.

The system on which the graceful acquirement of Bows and Courtesies is formed, ought thoroughly to be understood; and must be incessantly practised before the necessary ease required to be displayed can be attained.

Notwithstanding that Bows and Courtesies are generally deemed necessary to be observed even...

[page 17]

...in common intercourse with society, the neglect altogether in some, and the awkward attempts by others, in the use of so prominent a feature of deportment in the ball room, is truly shameful; so few are there out of the many, in the constant habit of frequenting the ball room to be found, making a bow, or courtesy, better than those never having entered one, from total disqualification.

The Bow and Courtesy require more ability in the teacher, and much more attention from the learner in their proper acquirement, than is generally understood, or believed to be necessary; and it is too common a case that many persons who have had every opportunity from superior situations in life of acquiring a knowledge of them, and their proper use, have still paid so little attention to the correct acquirement of the true principles, and have been so indolent in the practice of them, as to be no better than those in humble life, who, perhaps never received any other instructions, than those afforded at a day school. An instance decidedly conclusive as to the truth of this is deducible from the manner in which the Bow and Courtesy are made in such Country Dances as require a pause to answer to the time of the music, as in La Belle Catharine, The Haunted Tower, &c.; also at the commencement of Quadrilles, in which the capability of making the Bow and Courtesy properly, is easily to be discovered. Some persons will make the Bow, by suddenly jerking the head; others, by bending the head, and at the same time scraping the foot on the floor, in a manner peculiar to a country school boy; others, by bending the head nearly to the ground, are consequently prevented from resuming their situation, and performing the next figure in time for the music. ...

[page 18]

...It may frequently be observed, that persons, in bending, suffer their arms to hang in a manner seemingly void of animation; and others, aware of their own ignorance of the correct manner of Bowing, attempt to pass it off by a nod of the head.

Some ladies are equally reprehensible in their manner of making the Courtesy; who, instead of passing the foot into its proper position, and gently sinking, make a sort of motion that has acquired from the nature of it, the appropriate though perhaps not the most refined appellation of a sudden Bob; others, on the contrary, will make the Courtesy in a stiff, crude, and formal manner, equally disgusting.

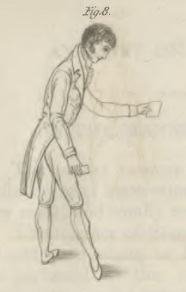

Figure 8. The Address Plate 1 Figure 4

To enumerate the different situations in which Bows and Courtesies are requisite to be observed and used in a graceful and becoming manner, would not accord with the limits of this work; however, it is necessary, that a description should be given of the manner of making them, as most frequently used, and in most general request.

The description will be confined merely to the shewing of what a Bow and Courtesy in principle consist, without any consideration as to the situations in which they are required; though it is necessary to mention, that there exists a difference in the making of them, according to different situations, whether in dancing or otherwise.

The gentleman, in making the Bow, will observe that his right or left foot, according to the situation in which he may become placed, should be passed from the first position shewn by Plate 1, Figure 1 [See Figure 6] into the second, shewn by Plate 1, Figure 2 [See Figure 6], the first position, should be then resumed; the knees preserved perfectly straight, and the head and shoulders gently inclined, tracing forwardly an...

[page 19]

...imaginary curved or bowed line, and returning to an upright posture in the same gradual and easy manner; making no rest during the inclination

of the head (see Plate 1, Figure 3 [See Figure 7]).

The lady in making the Courtesy, should pass her foot from the third position, (shewn by Plate 1, Figure 4 [See Figure 8]) into the second position, and bring it to the fourth position in front, gently sinking with the knees turned outwards to the sides; preventing, as much as possible, any forward projection of them (see Plate 1, Figure 5 [See Figure 9]); an attention to which will afford an easy equilibrium of the figure, so necessary to the graceful effect, capable of being produced, and most properly required. The more easy the performance of the Bow and Courtesy to the persons making them, so much more graceful to the spectator.

Figure 9. The Address Plate 1 Figure 5

Putting On and Taking Off the Hat

A graceful manner of putting on and taking off the Hat, requires very particular attention, in the Minuet; but, as the Hat is not now worn in the ball room on any other occasion, the gracefully putting on and taking off the Hat, becomes an embellishment in much more request out of the ball room, than any other article herein treated on, under the head of Deportment. The arm employed in putting on and taking off the Hat should be raised gently; particularly avoiding raising it angularly, but in a circular line, and by all means avoiding a sudden straight direction (see Plate 1, Figure 6 [See Figure 10]). The too common custom of exposing the inside of the Hat is not only exceedingly improper, but highly indelicate. The manner in which it should be held is shewn in...

[page 20]

...Plate 1, Figure 6 [See Figure 10]; and the manner of taking it off, and placing it on the head, in Plate 1, Figure 7 [See Figure 10].

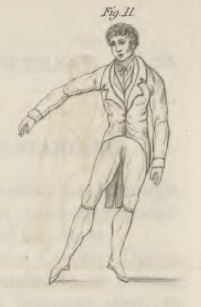

The Presenting of Any Thing by One Person to Another

To do which easily and well, is unquestionably requisite, as frequent occasion requires the presenting of a glove, fan, ticket, card of address, &c.&c. both within and without the ball room. The manner of doing it affords ample means of drawing comparison between the accomplished and the uncultivated - it requires ease and confidence; and, if done at the time of passing the person to whom the article is presented, a knowledge of the passing Bow, and of forming an easy circular movement of the arm, is requisite, (avoiding any angular bend at the elbow). In presenting it properly, the foot should be passed forward into the fourth position, the head a little inclined, and the arm raised in an easy curved form, by an attention paid to the movement of the elbow (see Plate 2, Figure 8 [See Figure 11]). Should the person be promenading, care must be taken that the Bow be made at a proper distance. Some of our principal Dancers and best Actors afford examples worthy of being copied, from their great practical knowledge of the true principles of beauty and deformity; having acquired confidence by so frequently having occasion to exercise the rules of grace, their consequent easy manner enables them generally to excel persons in private life. The reader is therefore recommended assiduously to practice the presenting any thing in all the different situations in which he may...

Figure 10. The Address Plate 1 Figures 6 & 7. The text reads The left hand is here used in presenting carriage of the hat &c. the right of the Dancer being frequently engaged with his Partner, when this is not the case, the right hand should be used.

[page 21]

...be at all likely to have occasion to perform the office.

The Manner of Entering and Leaving a Room

With ease and propriety, has ever been considered of so much necessary convenience and effect, that very few persons in general life neglect to make it a particular point in request in the education of their children; as teachers of dancing are almost invariably expected to give instructions to their pupils, in this essentially requisite part of the Address. * Numbers of persons frequently apply to teachers of dancing, with a view to the acquirement of this requisite only; as the manner of entering and leaving a room affords the necessary criterion, whereby to judge of good breeding. The graceful Bow and Courtesy are the principal requisites to be attended to, added to an easy graceful manner of introduction to the company present.

* See the Preface, for what is generally called, The Address.

On the Manner of Walking

Nothing perhaps is more varied in its style and manner than Walking, as two persons are rarely to be met with, who walk in the same style. To walk well ought certainly to be acquired, as an easy and genteel manner is so material to a graceful deportment.

Figure 11. The Address Plate 2 Figure 8

[page 22]

It is a habit with some persons to walk quick, and with others slow, each manner being correct according to circumstances; but the obvious defects in walking are shewn by those who use short jerking steps, drag their feet after them without animation, by some who raise the legs above the necessary height in the manner of stepping over a stone, &c. while others are seen shuffling on, with their toes turned in, and knees bent forward; and some persons may be seen skipping on the toes only; others are gliding along on their heels. Independent of any natural deformity, the above defects are exhibited daily; but never in those persons having any regard for the opinions of observers.

To walk well, an attention to an easy carriage of the body, and proper elevation of the head will be required, and all stiffness must be avoided, the steps lengthened proportionately with the height of the person, the tread firm, with the knees straight; avoiding walking wholly on the toes or heels. The hips, knees, and feet corresponding, in being turned outwardly, and the weight of the body alternately resting on the foremost foot, the other becoming raised, prepared to pass forward, &c. The arms preserved in an easy manner by the side, avoiding by all means the ungraceful habit of swinging them backward and forward (see Plate 2, Figure 9 [See Figure 12]). In promenading in the ball room particularly, a graceful manner of walking is most essentially requisite, as therein every opportunity is afforded of displaying the figure to advantage. In the slow promenade, or march, the body must be carried in an easy graceful manner, and the toes pointed in their proper positions.

[The two image plates are bound here in the publication]

[page 23]

On the Manner of Standing

The proper manner of Standing has, through idleness and inattention, been carelessly treated by some, and totally neglected by others.

The manner of Standing in a Country Dance ought particularly to be attended to, as a loose deportment in this respect becomes open to observations, not only of the persons in the dance, but also of the spectators, and only serves to create contempt through the disrespect such carelessness evinces. The first and third positions are the most proper in which to stand easily, as the body may be kept erect with a suitable elevation of the head, without any apparent stiffness. [See Figure 12]

Figure 12. The Address Plate 2 Figures 9 & 10

Should the set be composed of many persons, and a great length of time consequently occupied in standing, the positions may be varied, and will not only suit the commencing movements when called into action, but the habit will be avoided of resting the body on one leg to relieve the other, producing an effect truly inelegant, the person so standing appearing to have a dislocated hip. Standing in the set, with the arms crossed, or with the hands in the pockets, is extremely improper, and ought to be avoided.

On the Motion and Carriage of the Head

In Dancing, an appropriate motion of the head is essential in producing the requisite effect.

[page 24]

According to the turns of the body, and movements of the feet, the Head should be moved in an easy, graceful manner, (see Plate 2, Figure 11 [See Figure 13]); a pleasant countenance contributes greatly to an improved effect, and takes away all appearance of labour, in performance of the several movements.

The head, in some parts of the dance, when held in an elegant and dignified, yet easy and graceful situation, gives to the whole a distinguished effect.

In all motions of the head, and in changing one position to another, all sudden motions must be avoided, and the positions suffered to fall into each other with a graceful inclination.

It must be remarked, that a projection of the chin is a real distortion of grace, as applied to movements of the head. Holding down the head breaks into the rules of Grace, applicable to the Body, &c. is a bad habit, equally prevalent in walking or dancing, and, as it implies bashfulness or inability, ought particularly to be avoided.

On the Use and Carriage of the Arms and the Giving or Presenting of Hands

Figure 13. The Address Plate 2 Figure 11

In the majority of the Movements and Actions of the Figure, the Arms are essentially employed; yet proper attention is rarely paid to the acquisition of an easy manner of using them.

Foreigners have been known to accuse the English of ignorance of properly disposing of the arms, in standing, walking, &c. It is to be hoped, that this accusation is but partially founded.

[page 25]

Amongst Quadrille and Country Dancers, a more graceful carriage and easy command of the arms are much wanted, and their acquirement ought not to be neglected; as there are but few movements where an opportunity is not afforded of shewing and displaying the person to great advantage, in the gracefully giving the hand, either to the partner, or in performing the figure to any other person, particularly in all those figures where turning, swinging, or leading occur, as in Swing Corners - Turn Corners - Hands Across - Hands Four and Six Round - Lead Outside - Down the Middle - Chaine des Dames - Chaine Angloise, - Promenade, &c. &c.

In presenting and joining hands, either with partners or with any other persons, angular or straight lines must be avoided, and the arms raised in an easy manner, so that from the tip of the finger to the shoulder shall be formed a gentle curve; taking especial care, that whether one hand, or both be joined, they be not raised above the level of the shoulder; except the figure of the dance be such as to require it; as in The Triumph - La Pastorelle , &c..

The too frequent practice of moving the arms up and down, in Leading down the Middle is an extravagant impropriety, and disgraceful to those who use it in genteel company.

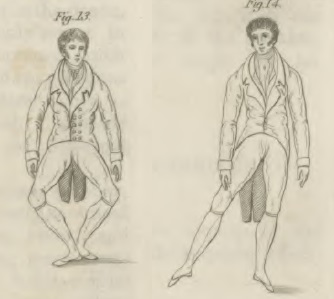

In the performance of the figures where Swinging and Turning are used, a proper distance from each other of the persons joining hands is requisite to prevent the bending of the elbows, which produces the ungraceful attitude of two Angles, instead of one Serpentine line (see Plate 1, Figure 12 [See Figure 14]).

The palms of the hands must not, in any instance, be turned upwards; and in joining of...

[page 26]

...hands, it is quite sufficient to use the fore finger and thumb only. To grasp the whole hand, as some rudely do, is altogether improper, and in good company considered an unpardonable freedom.

Bearing down and improperly confining the hands, complaints of which are repeatedly made in the ball room, call for loud and severe reprehension.

It is a common practice with some gentlemen, constant frequenters of the ball room, instead of gently taking the hands of the ladies, as before mentioned (see Plate 1, Figure 12 [See Figure 14]) to grasp and confine them so closely, as to prevent their being disengaged in proper time; and frequently in Leading down the Middle, to bear down the hands of their partners, and suspend on them nearly their whole weight. Being thus consequently obliged to dance double with bent knees, and prominent elbows, all appearance of grace and elegance is lost, by a display of vulgarity in the extreme.

Figure 14. The Address Plate 1 Figure 12

On the Carriage and Motion of the Body

Notwithstanding that so much depends on the carriage of the Body, generally, in its influence and operation on the other parts of the figure, little attention is paid to it. The effect of its proper use may be witnessed in the performance of some principal dancers, who display a correct deportment of the Body to so much advantage in their execution, by the Legs and Feet, and the use of the Arms, &c.

[page 27]

A proper deportment of the Body is essentially necessary in walking as well as dancing, &c. It should appear neutral on most occasions, by not apparently joining in the rapid movements of the legs and feet, or in forming and changing the attitudes by the arms, &c.

The Body held firm and upright, avoiding stiffness; the shoulders drawn easily back, the movements of the thighs and legs taken from the hip, and the arms used appropriately, without seeming to disturb the proper carriage of the body, will give the general effect of the figure necessary to be produced, by all who wish to excel in graceful deportment. The proper manner is shewn by the figures already referred to.

Affectation in Dancing

Should most particularly be avoided, not only as disgusting, but also as tending to prevent the whole performance of the figure as correctly set. For instance, some persons may be observed in the ball room, who are excellent dancers, and consequently despise the efforts of others; and in going down a Country Dance, or standing in it as neutral, when they are required to Turn or Swing Corners, or take the hands in Leading Across, Setting and Changing Sides, &c. affectedly omit what is correct, and dance round the lady or gentleman, with whom they should turn as the figure requires. Also in Quadrilles, in Chaine Angloise, & Chaines des Dames, the same will apply.

Such conduct betrays an ignorance of that which ought to be remembered, that all persons...

[page 28]

...standing up in a Dance are alike entitled to civil and polite attention.

Execution of the Feet

A proper execution of the Feet necessarily belongs to correct Deportment in Dancing, as it renders the persons observing correct execution distinguishable from those who presume to stand up in a Dance, ignorant of proper steps, and who not only consequently introduce a variety of grotesque movements, to the danger of those who are in the Set; but instead of performing the figure to the same time in music, and in the situation directed by the figure of the dance. In Set and Change Sides, for instance, one person will have crossed the Set, before another has finished the Setting, as adapted to the figure and Music. So far as the proper execution by the Feet, of the Steps necessary in the performance of the figures belongs to Deportment; and where good Dancing, coupled with Deportment, has the ascendancy, is strikingly observable in the correct performance in Quadrilles where Pas Seuls are to be performed, as in La Pastorelle &c. also in the Country Dance Figures of Set and change Sides - Set contrary Corners - Set three Across - Set three in your Places - Set half Right and Left. For, if otherwise than correctly performed, one person will very probably run against another, and destroy the sociability of the Dance, from the consequent confusion.

The Steps are composed for the correct performance of the various figures to the times...

Figure 15. The Address Plate 2 Figures 13 & 14

[page 29]

...and measure or music thereto adapted; it is contrary to correct Deportment when they are not properly applied.

To produce the necessary effect in point of graceful execution, all the movements are properly performed from the hip; and those that require bending, by the knee, preserving the body straight and easy (see Plate 2, Figure 13 [See Figure 15]), and in rising, straightening the knee, turned outwardly in the same direction, the toes pointed downwardly (see Plate 2, Figure 14 [See Figure 15]).

The introduction of Steps composed for and adapted to any other species of Dancing must be avoided; shuffling and rattling of the feet, as used in Hornpipe Steps, and the flat footed movements of Spanish Dancing, are incompatible with those in Quadrilles and Country Dancing; and, when introduced, tend to draw on the performer, the contempt of the more enlightened part of the company.

Looking at the feet, whether in Dancing or Walking, &c. is a bad habit, too frequently practised, and calls for reprehension; independent of the affected appearance produced by its impropriety, it not only bespeaks vanity, and an exclusive opinion of ability, but the better effect to be displayed by the figure is lost.

Snapping the Fingers, &c. in Dancing

The impropriety of snapping the Fingers in Reels, and using the sudden howl or yell, which partakes of the customs of barbarous nations, is directed to be avoided in the Article under...

[page 30]

...the head of The Etiquette of the Ball Room. * It is necessary here to mention that such practices are entirely contrary to correct and genteel Deportment.

* See my Companion to the Ball Room.

On the Deportment of the Person in Quadrille Dancing

Quadrille Dancing has now become so general, that most persons who visit the Ball Room, will now (as they have been used to do in Country Dancing) venture to stand up in a Quadrille, and it is in general observed that two thirds of such persons have either never learnt, or been badly taught; so that their knowledge at furthest consists of an imperfect idea of a few of the most simple figures; and, by way of excusing their inability, they declare that nothing more is wanting.* A proper knowledge of the steps, so requisite in Quadrilles, or any attention to the carriage of the arms or deportment of the person is by them wholly neglected.

Now, as this department of Dancing, from its open form and construction, and requiring only a small number of persons to form the Sets, renders all in those sets conspicuous in their movements, and unlike the English Country Dance, where, by the number and closeness of...

[page 31]

...the sets, want of ability may sometimes pass undiscovered; but in Quadrilles, Dancers not only stand conspicuous to the company, and those in their own set, but there are frequently pas seuls for each person.**

Then let it be imagined how such persons must feel, were they sensible of the ridiculous figure they make, shuffling backwards and forwards, without knowing how or where to place their feet, or paying the least attention to the carriage of the arms and body. As a graceful deportment is more required in this department than any other, the Dancers being more exposed to view, great attention should be paid to the giving the hands gracefully in Chaine Anglaise Chaine des Dames, & Tours de Mains, and in carriage of the arms in Promenade; also in taking the hand of your partner, En Avant, & En Arriere, &c. or in any other movement that requires the gentlemen to lead the ladies. Without a graceful carriage of the arms, and an easy deportment of the whole person, no one can be considered a good Quadrille Dancer.

* This is chiefly to be attributed to certain teachers of Dancing, who propose to complete the learner in this department of the Art, in a few lessons, at low prices; but such completion consists only of a slight knowledge of a trifling step or two, and a few of the most simple figures, and the pupils are induced to believe that nothing more is wanted.

** For a correct idea of the form and construction of the various Quadrille Figures, see my Quadrille Panorama, in which all the various forms are accurately described by Diagrams.

On the Deportment of the Person in Waltzing

It is too frequently observed, that in public assemblies, persons are to be found, who not only Waltz in an awkward and inelegant manner;...

[page 32]

...but by hugging and dancing so close to their partners, stamping with their feet, bending forward at their knees, and poking out their elbows, disgust the spectators, and prove unpleasant to their partners; this method of Waltzing is not only objectionable to the company, but tends to bring this elegant species of Dancing into disrepute, which if well performed according to the * Rules laid down, will be found to be one of the most elegant and interesting departments of the art. It is not alone sufficient to make a good Waltzer, to have a correct knowledge of the steps, or a brilliant execution of the feet; but they must be united with a graceful carriage of the head and arms, and an easy and elegant deportment of the person.

From the foregoing observations it will be obvious to the Reader, that to Dance gracefully every attitude and every movement must be made, so that nothing shall appear studied; for whatever seems studied, seems laboured, and that execution by the feet is not alone sufficient to excite admiration, or accord with true taste, but a graceful Deportment of the whole Figure, and having it thoroughly at command is also requisite; so that each feature will correspond properly with each motion and action of the other.

* See my Correct Method of German and French Waltzing, in which the proper steps are accurately described, and the various positions of the Arms, shewn by full length figures, in the most admired positions in Waltzing.

[page 33]

On Salutation at Meeting and at Taking Leave

These ceremonies are varied in different countries, according to customs peculiar to each. It is here only intended to give the outline of the most proper modes to be observed in this country; the discretion of the Reader will enable him to adapt such occasional variation, as circumstances may require.

The introduction of a lady or gentleman to us, when seated, is a frequent occurrence; if such person, at the time of being introduced, should be standing, politeness requires us to rise and make an obeisance, or present the hand, according to circumstances.

The custom of shaking hands should be confined to those who are on equal terms, or in equal rank in society - to extend the practice further, might sometimes be thought an improper liberty, and give offence; but, if the hand is first presented by a superior, it should be accepted. There seems also to be a kind of caution prevalent with us in this country, similar to that recorded of the Roman General Sylla, who when Mithridates offered him his hand, observed, that before he took it, he wished to know whether he

took the hand of a friend or an enemy.

In the street, or in the open air, on accosting or meeting a friend, or even a stranger, it is unnecessary and improper to take off the hat, as is the practice of some foreigners, in whose native climates that custom prevails; but in this country, in inclement seasons, it would be highly...

[page 34]

...inconvenient, and had much better be avoided altogether, under almost any circumstances, as it carries the appearance of mean servility, and would subject any one to the derision of the vulgar. It is quite sufficient to touch the hat, bowing at the same time in a short, easy, and graceful manner; the custom of drawing back the foot at the time, has an awkward rustic appearance, and must be avoided. On taking leave, the ceremony of touching the hat, and bowing, or of shaking hands, is a proper mark

of attention to be observed.

It is scarcely necessary to remark, that on such occasions, the right hand should invariably be used without the glove.

Holding any person by the button, or any part of the cloaths, looking down at the feet, or taking particular notice of any part of their dress, looking off in another direction, or any other mark of inattention, must by all means be avoided.

FINIS

[The final two unnumbered pages are Wilson's advertisement for Tuition in Dancing, see Figure 5]

Conclusion

Wilson's 1821 The Address was not one of his better known works, either two hundred years ago or today. It is however a fascinating insight into the mind of a dance professional attempting to write about grace and elegance in the ballroom. Both the observations shared and the topics left unaddressed offer the modern reader a glimpse into the historical context in which Wilson operated. It is well worth reading for anyone interested in historical social dance.

Many modern readers may have enjoyed movie and televisual depictions of Regency ballroom scenes. Such performances tend to the fantastical and perfected, a hobbyist might feel obliged to achieve the same degree of perfection in their own dancing. Wilson's work is fascinating, at least in part, as it emphasises what a dancing master of the early 1820s thought to be important in elegant ballroom dancing. He wrote for the benefit of real people of his own day, in so doing, he preserved a unique insight into Regency dance culture for the rest of us too. If Wilson were alive today, he might not recognise the ballroom scenes of many costume dramas as being at all representative of the dancing of his own day!

We'll leave the study at this point, if you have any additional information to share on these subjects then to please Contact Us as we'd love to know more.

|