|

Paper 67

Mons. Boulogne's Gymnastic Morris Dance , 1827

Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor

[Published - 17th December 2023]

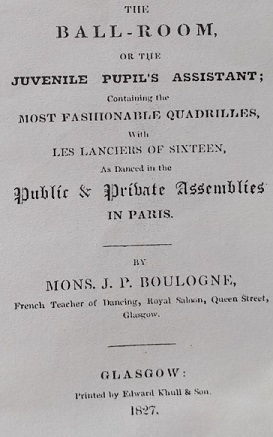

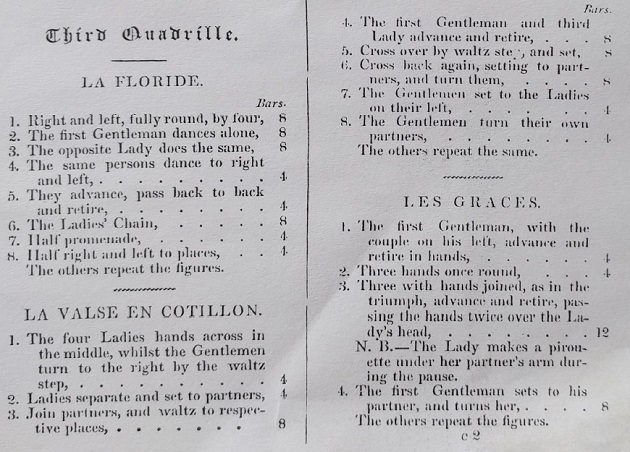

Figure 1. The Ball-Room, or the Juvenile Pupil's Assistant, 1827, by Mons J.P. Boulogne

A curious little book was published in Glasgow back in 1827 by Monsieur J. P. Boulogne under the name The Ball-Room (see Figure 1). This book contained notation for a variety of different dances, one of which stands out as being particularly unusual - it was described as being a Gymnastic Morris Dance, with sticks . This is particularly interesting as, if we are to believe the title given to it, this may be the first choreographed Morris dance to ever have been published. In this paper we'll investigate what is known of the author, the book itself and the phenomenon of Morris Dancing in the early 19th century; finally we'll consider the dance itself.

I must stress at the outset that I am not an authority of Morris Dancing, neither modern nor historical. I will attempt to write about the material based on its own merits and in comparison to other similar works of around the same date; I hope to avoid any significant blunders in my appreciation of Morris, if you spot any errors do please get in touch and I'll correct them. I'd also like to acknowledge a significant debt of gratitude to Michael Heaney who has helped me to navigate the maze of 19th century Morris references, I can very much recommend his book The Ancient English Morris Dance to anyone who's interested to read more.

John Peter Bologna (1775-1846) / J.P. Boulogne

The author of our mysterious book gave his name as Mons. J. P. Boulogne on the cover of the publication. There are precious few biographical details of the author to be found within the book. He claimed to be familiar with what was being danced at the public & private Assemblies in Paris , he described himself as being a French Teacher of Dancing at the Royal Saloon, Queen Street, Glasgow . Neither of these statements is particularly informative. There is slightly more to be gleaned from the brief introductory text on the first page of the book: As Mons. B. is a native of France, and has frequent communications with Paris, he will regularly be made acquainted with any variation of style in his profession; and he trusts, by his steadiness and unremitting attention, to merit the patronage and support which he hopes to receive . We are informed that Boulogne was a Frenchman, had frequent news of new dance styles from France, and was also a tutor of dancing. Thereafter the biographical details from the book itself run dry.

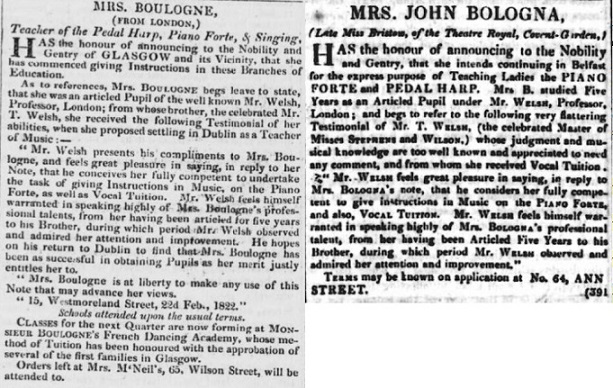

A little further information can be found printed in the pages of Glasgow's newspapers. Several advertisements were issued between 1826 and 1828 on behalf of either Monsieur Boulogne or his wife Mrs Boulogne . The first was issued by Mrs Boulogne in the Glasgow Herald newspaper for the 6th of January 1826 (see Figure 2, left); she described herself as being from London and as being a Teacher of the Pedal Harp, Piano Forte, & Singing . She wrote that she Has the honour of announcing to the Nobility and Gentry of Glasgow and its Vicinity, that she has commenced giving Instructions in these Branches of Education. As to references, Mrs Boulogne begs leave to state that she was an articled Pupil of the well known Mr Welsh, Professor, London; from whose brother, the celebrated Mr T. Welsh, she received the following Testimonial of her abilities, when she proposed setting in Dublin as a Teacher of Music:- Mr Welsh presents his compliments to Mrs Boulogne, and feels great pleasure in saying, in reply to her Note, that he conceives her fully competent to undertake the task of giving Instructions in Music, on the Piano Forte, as well as Vocal Tuition. Mr Welsh feels himself warranted in speaking highly of Mrs Boulogne's professional talents from her having been articled for five years to his Brother, during which period Mr Welsh observed and admired her attention and improvement. He hopes on his return to Dublin to find that Mrs Boulogne has been as successful in obtaining Pupils as her merit justly entitles her to. Mrs Boulogne is at liberty to make any use of this Note that may advance her views. 13. Westmorland Street, 22nd Feb, 1822. . The advertisement ends: Schools attended upon the usual terms. Classes for the next Quarter are now forming at Monsieur Boulogne's French Dancing Academy, whose method of Tuition has been honoured with the approbation of several of the first families in Glasgow. Orders left at Mrs McNeil's, 65 Wilson Street, will be attended to . We learn several things from this. Mons and Mrs Boulogne are implied to have been married at some date prior to February 1822 when the testimonial was issued; Mrs Boulogne had been an articled apprentice for five years prior to that (perhaps commencing in late 1816 or early 1817). She had intended to move to Dublin in 1822, and perhaps she had in fact done so; by early 1826 she had moved to Glasgow and was available at her husband's Dancing Academy. The dancing academy itself had existed in Glasgow for a sufficient period of time to already have pupils from among the first families of Glasgow. We might therefore suspect that it had opened at least three months previously in late 1825.

Figure 2. An advertisement for Mrs Boulogne's services, Glasgow Herald, 6th of January 1826 (left); a similar advertisement for Mrs Bologna's services, Belfast Commercial Chronicle, 16th of October 1822 (right). Images © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Images reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive.

The next such advertisement was issued by Mons Boulogne, once again in the Glasgow Herald newspaper, this time for the 15th of September 1826. Boulogne wrote that his French Dancing Assembly will re-open for the Season, on Wednesday next, the 20th September, 1826 . He continued Mons Boulogne begs leave to return his grateful acknowledgements to the Nobility and Gentry of Glasgow and its Vicinity, for the very liberal patronage bestowed on him last Season, when he opened his French Dancing Academy in this City. He was very sorry that, owing to the late period of his arrival here, he was unable to provide suitable accommodation for his Pupils; but he has now the honour to intimate, that he has got the Royal Saloon, Queen Street, which, from its commodiousness, will enable him to bring forward several novelties this season, which the want of room prevented him doing last Winter. Mr B. has procured from Paris the Original and Proper Set of the much admired Sixdrilles, as danced by the Noblese in that Capital, and which is so convenient in parties when the number of Ladies predominates. He will also bring forward the Italian Carnival Quadrilles, the original set of which he has obtained from Italy. M. B. when in London this Summer procured from the French Lady who gave so much satisfaction in the Argyle Rooms a Set of the necessary apparatus for training his Pupils in the Gymnastic Exercises, in so far as applicable to Dancing, and improvement in Carriage. This is the first attempt of the kind in Scotland, as it is perfectly different from the system at present introduced for the benefit of young Gentlemen. Mrs Boulogne respectfully intimates that she has this Season got convenient apartments for her Academy at No 69 Glassford Street, where she Teaches the Pedal Harp, Piano Forte and Singing; and as she was an articled Pupil of the celebrated Mr Welsh of London, she hopes to give satisfaction to those who honour her with their patronage. . From all this we learn a bit more. The Boulogne's were fresh arrivals in Glasgow in late 1825, thus they had lacked proper accommodation for their pupils for the previous winter season. That had since been corrected and both now had suitable studios for their respective academies. Mons Boulogne had evidently returned from a trip to London shortly before issuing this advertisement, he had studied in (amongst other things) Gymnastic exercises while there and would offer such tuition in Glasgow. His tutor in London may have been Miss Marian Mason, she certainly offered tuition in Gymnastic and Callisthenic exercises at the Argyll Rooms in early 1826 (Morning Post, 11th of April 1826).

We also learn something from the above advertisement that gives me cause to question whether Mons Boulogne was being entirely honest with his readers. He mentioned that he had procured from Paris the Original and Proper Set of the much admired Sixdrilles, as danced by the Noblese in that Capital ; this may be a true statement, there are however reasons to be suspicious. The Sixdrilles were a form of dancing that emerged in mid 1825 and were, as best as I can discern, first invented and taught in the English city of Manchester by a dancing master who gave his name as Monsieur Paris (Manchester Guardian, 25th of June 1825). In the months thereafter the Sixdrilles would be referenced in newspapers issued across the north of England and the South of Scotland, invariably implying that they were derived from the city of Paris itself. And yet I know of no evidence of their actually having been danced in Paris; I suspect instead that dancing masters taught them on the assumption that they were from Paris, doing so on the basis that other dancing masters were also claiming that they were from Paris. Thus I have my doubts about our Mons Boulogne having procured them from Paris; I suspect instead that he'd received the dances from a professional colleague who had in turn procured them from another professional colleague, and that they ultimately derived from Mons Paris of Manchester. This is however a matter of speculation, further evidence may yet emerge of a genuine Parisian origin for this dance. If our Mons Boulogne was being disingenuous, the same was true of a good number of other dancing masters at around the same date.

Figure 3. Mr J Bologna (left) and Mr J Grimaldi (right) in The Comic Dance from The Favourite Pantomime of Mother Goose. Image courtesy of the Wikimedia Foundation.

Moving on to 1827, a further advertisement was issued once again in the Glasgow Herald for the 28th of September 1827. Mons Boulogne promised that his academy at the Royal Saloon would reopen on the 1st of October. He continued: Mons. Boulogne, Who was the first to introduce the Gymnastic Exercises into Scotland, begs leave to intimate to the Nobility, Gentry, and Inhabitants of Glasgow and its vicinity, that his style of teaching is founded on the true principles of the Art, embracing the most recent improvements introduced in the first circles, and in all Academies in Paris and London. Mons B. made it his study, this Summer, to collect all the newest, most admired, and Fashionable Dances, as practised at present in Paris by the Noblesse. He has also acquired the recent improvements in Gymnastics. The room is fitted up with the necessary Apparatus for training his pupils in the Gymnastic and Callisthenic Exercises, as performed at the Academy Royal, Paris, for giving gracefulness to the carriage, manner, and deportment. Those Exercises are allowed to be the very best practice for Young Ladies and Gentlemen, and Mons B. intends to devote to them his most particular attention. . He went on to advertise two levels of tuition; his Academy for First Circle on Monday, Wednesday and Saturdays; and a Second Class Academy on Tuesday, Thursday and Fridays. He continued: The Academy is open, every other Evening, at 8 o'clock, for the instruction of grown Ladies and Gentlemen in the fashionable mode of dancing Quadrilles, Waltzes, Spanish, Scotch and English Country Dances, and Sixdrilles, the latter of which are so convenient in parties where the number of ladies predominates. He concluded: Mons Boulogne's Books of all the new Dances are published, and to be had, with Cards of Terms, at all the Music Warehouses and Libraries . We learn that Boulogne had once again visited London over the summer and that he was particularly proud of his Gymnastic tuition. We also learn that his books of all the new Dances was published, this is presumably a reference to the very same The Ball-Room book that we are studying.

Moving forward to 1828, a final advertisement was published in the Glasgow Herald for the 26th of September 1828. Boulogne wrote: Monsieur Boulogne's Royal Saloon French Dancing Academy is moved to the large Hall in Hutcheson's Hospital, Ingram Street, Which is fitted up in a most tasteful style of elegance, after the Parisian manner, D'Academie de Dance. Mr Boulogne begs to intimate, that having returned from his native home, Paris, he will Re-open on Wednesday first October, with all the graceful and elegant improvements now so justly admired in Paris and London. Mons B having been established as a Ballet and Dancing Master in London, and having for the period of 14 years served in L'Academie Royale, Paris, and the King's Theatre, London, he presumes that, without incurring the charge of presumption, he is entitled to claim the reputation of a finished Teacher . In this final advertisement we learn that Boulogne had once again travelled, had moved his academy to a new address, and that he claimed to have been a professional dancer for some 14 or more years (dating at least back to 1814).

And yet the story does not end there. We may recall that Mrs Boulogne implied that she had been in Dublin prior to moving to Glasgow (see Figure 2, left). It transpires that she had indeed been in Ireland, both Dublin and Belfast, only she performed under the name Mrs Bologna. For example, she published an advertisement in the Belfast Commercial Courier for the 16th of October 1822 in which she quoted from the exact same letter of approbation from Mr Welsh as we found quoted in Glasgow in January of 1826, only this time she gave her name as Mrs John Bologna (Late Miss Bristow, of the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden) (see Figure 2, right). This was not the only such advertisement, the letter was referenced in several newspapers over several years and there can be little doubt that it's the same lady in each case. We now know both her maiden name and her husbands first name! She had evidently been a performer for the London stage. It's unclear why they changed their name but it may have only been a temporary phenomenon, she would revert to using her prior name of Mrs Bologna professionally in Glasgow from 1831 (eg The Scotsman, 8th of October 1831).

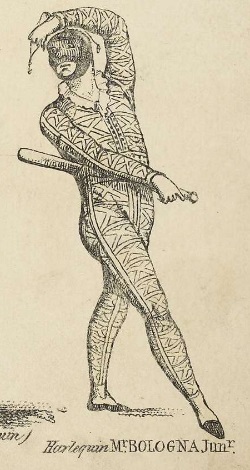

Once we know that they operated under the name Mr and Mrs Bologna a wealth of new biographical references emerge (not least of which is his Wikipedia page!). His full name was John Peter Bologna, he was born in 1775 and died in 1846. His family were of Italian extraction, his father and siblings had all enjoyed significant success on the London stage. They may have been related to the Signor Bologna who was credited as having performed the first marionette Mr Punch Show in London back in the 17th century (the forerunner to the modern Punch and Judy show). Our John Bologna was often credited as Bologna Junr in playbills (see for example Figure 4), this was to disambiguate him from his father, they often appeared on stage together with his father sometimes performing in the role of a clown.

There's a brief biography of the family in the 1838 Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi (1778-1837, also a celebrated clown); it reveals that John Bologna, who was also known as Jack , married Louisa Maria Bristow, the sister of Grimaldi's second wife. Jack and Louisa were married in Westminster in May 1818 (I'm indebted to Michael Heaney for finding their marriage certificate). He was described by Grimaldi as being a well-known harlequin (see for example Figure 4). Bologna was a regular performer on the London stage throughout the first two decades of the 19th century. He was highly talented, an advertisement from 1825 (Belfast Commercial Chronicle, 7th of February 1825) even announced a series of ventriloquism performances that he would offer. He was also known for crafting clever stage machinery; for example, an 1822 advert (Saunders's News-Letter, 29th of January 1822) described in detail his Original Pictoreal Theatre of Arts and Dominion of Fancy , it was said to be a mechanical marvel opening in Dublin. Our mysterious J.P. Boulogne was one of the most famous comic performers, and perhaps also stage innovators, of his generation!

Figure 4. Mr Bologna in the role of Harlequin from Harlequin and the Red Dwarf, 1813. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

We can only speculate as to why he chose not to make his past better known in his Glasgow advertisements of the later 1820s. One possibility is that he had hoped to leave comic theatre behind and to present himself as a serious and successful ballet master, which he undoubtedly was; tuition in social dance had always offered an honourable retirement career for former stage performers, perhaps that's what he wanted for himself. Perhaps he changed his professional name to distance himself from whatever presuppositions his prospective students may have had of him. However it came to be, our J.P. Boulogne and London's Jack Bologna were indeed the same person. He somewhat obfuscated his past; he may (perhaps) have genuinely been born in France though his family were of Italian extraction; he may (as he claimed) have performed in the theatre in Paris, yet it was in London that he became a celebrated household name. He had largely retired from the London stage by around 1820, he and Louisa evidently spent a few years in Ireland before moving to Glasgow. It's likely that his identity had become known in Glasgow by 1828, his final known advertisement of 1828 went to some effort to defend his balletic credentials; by 1831 his wife was actively using their London name. Thereafter he appears to have suffered a slow decline. It was in Glasgow that he is understood to have died in 1846, apparently at that time a penniless man.

Boulogne's The Ball-Room publication, 1827

Having investigated the mysterious author of The Ball-Room, or the Juvenile Pupil's Assistant, let us now consider the book itself (see also Figure 1).

It was published in Glasgow in 1827 and (according to the cover) offered the Most Fashionable Quadrilles, With Les Lanciers of Sixteen, As Danced in the Public & Private Assemblies in Paris . The book spans 48 pages and contains the figures, but no music, for a selection of mostly ballroom dances (see, for example, Figures 5 and 6). The author explained the purpose of the book in an opening address: I have been induced to publish the following Selection of Dances, even at the hazard of encountering the criticism of the Public, by the earnest solicitation of my Pupils, for whose benefit principally it is intended. To all of them, especially those of more tender years, I hope it will be found a valuable assistant, enabling them to recall at pleasure these Figures, which, though they may have been delightful in practice, and committed to memory with great care, may yet, amidst the variety of studies to which they must necessarily attend, have been forgotten. I have been careful to select those Dances that are just now the most admired in these great Circles of Fashion and Taste, London and Paris, especially Quadrilles and Sixdrilles, as danced by the Noblesse in these Capitals, and which is so convenient in parties where the number of Ladies predominate. He will also bring forward the Italian Carnival Quadrilles, the original set of which he has obtained from Italy . And so we read that Boulogne/Bologna expected the book to sell primarily to his own students.

Figure 5. Example pages from The Ball-Room, or the Juvenile Pupil's Assistant, 1827.

The author claimed to have been careful to select only the most admired dances from the circles of fashion in London and Paris. I can't say with any certainty whether he succeeded; my impression is that the book contains dances that he would be expected to teach, believing them to be from London and Paris, regardless of whether that were actually true or not. That is, they're dances that the author might genuinely believe to have been popular in London and Paris, without the first-hand knowledge to know whether they truly were popular; other authorities claimed Parisian origin for some of them so he might do so too.

It's a book that would, to some extent at least, have been in competition with the Lowe Brothers' Ball Conductor and Assembly Guide that was published in Edinburgh in 1822; we've written about it in a previous paper. It might also have been in competition with Bolton's Ball Conductor which was advertised to have seen it's 4th edition printed in 1829 (Glasgow Herald, 18th of September 1829). I've only studied the 1831 third edition of the Lowe Brothers' book, I know of no surviving copies of the Bolton book, it's therefore difficult to know to what extent the three books overlapped in content. It seems possible that the Bolton text of 1829 might have been heavily influenced by the Boulogne text of 1827. We've shared some wild speculation on this subject in a previous paper, you might like to follow the link to read more.

Let us now consider the individual dances within the Book.

- Les Lanciers Quadrille, as Danced in Paris (for 16 dancers). The Les Lanciers quadrille was the finale dance to the popular set of Lancers quadrilles that emerged from Dublin in 1817. We've written of The Lancers elsewhere if you'd like to read more. The Boulogne arrangement was interesting as it was arranged for sixteen dancers rather than the more usual eight. This is achieved by having two couples standing side-by-side on each of the four sides of a square; there would thereby be four head couples and four side couples. The normal figures of the Quadrille are adapted slightly to make this pattern work. It's rare to find a choreography printed for sixteen but it's not that uncommon to find references to Cotillions and Quadrilles having been danced by sixteen people; I suspect therefore that this arrangement was not new, it's likely that it had been enjoyed socially, perhaps even in London and Paris as the foreword promised.

- Italian Carnival Quadrilles, consisting of Le Caprice, Aladin Dance, La Tabatiere, She Bothers Me So, La Finale (Marche D'Aladin). I'm not familiar with these Quadrilles from elsewhere, except in so far as they also appear within the advertisements of the Bolton family in Glasgow in 1826. They were evidently believed to be of Italian origin; their content is nothing particularly remarkable, they don't stike me as especially different to any other quadrille sets that circulated in Britain from the late 1810s. We know from other sources that different localities around Britain often had local favourite Quadrille sets that would be unknown in other areas of the country, perhaps this Set of Quadrilles was simply popular in Glasgow in the mid 1820s. Local dancers were perhaps expected to know how to dance them.

- Figures of the Lanciers' Quadrilles consisting of La Dorset, New Lodoiska, La Native. These Quadrilles are fairly standard arrangements of the remainder of The Lancers, omitting only Les Graces and Les Lanciers. They're arranged for the normal eight dancers.

- Le Minuet Quadrille (Performed with the Minuet Step). This dance is a reasonably normal arrangement of the Le Pantalon quadrille, just with the specific instruction to dance it with a

Minuet Step . There's no particular reason why this would be difficult to achieve, assuming the music were suitable, it's a little unusual to actually find it in print however. The main difference compared to the more normal arrangement is that where we might have expected a Balance et tour de deux mains figure, this Quadrille instead has Turn right hands, The same with the left hands . We've written of Le Pantalon elsewhere, you might like to follow the link to read more.

- Gymnastic Morris Dance, with Sticks. This is the most unusual dance in the collection, we'll discuss it further below.

- Cotillon De La Sabotiere. This appears to be a fairly normal Quadrille or Cotillion dance, except in so far as all eight dancers are involved in each iteration of the figures. This was normal for Cotillion dances, less so for Quadrilles; it might perhaps be suitable as the finale of a typical Quadrille Set of the late 1810s. I'm not familiar with this particular dance from elsewhere.

- La Cotillon Du Roi. This appears to be another Cotillion or Quadrille dance, though a little more unusual. I've not familiar with it from anywhere else.

- Persian Quadrille. This is a fairly ordinary Quadrille figure, I'm not familiar with it from anywhere else.

- French Assembly Reel. This is a fairly ordinary Quadrille figure, I'm not familiar with it from anywhere else.

Figure 6. More example pages from The Ball-Room, or the Juvenile Pupil's Assistant, 1827.

- Second Set of New Quadrilles consisting of La Garde Royale, La Belle Parisienne, L'Aimable, Le Tableau, Le Champ De Mars. This is a fairly ordinary set of Quadrille dances that I'm not familiar with from anywhere else. They've been arrange to be compatible with the First Set of Quadrilles.

- Les Cuirassiers. This Quadrille is prefixed with the title

New Figure and terminated with This dance may be used as a finale, or danced by itself . Despite the similarity in names this Quadrille seems unrelated to the Les Cuirassier set of Quadrilles published in London by G.M.S. Chivers in 1821.

- The Sixdrilles consisting of Figure Des Pantalons, Figure De L'Ete, Figure De La Poule, Figure De La Trenise, Figure La Finale, La Garcon Volage. The sixdrilles are a fascinating dance format that we're likely to study more closely in a subsequent paper. They reimagine the figures of the First Set of Quadrilles so that 12 dancers (three per side of a square) can dance them. The final dance in the collection, La Garcon Volage has taken the name of the first Quadrille of Edward Payne's c.1816 5th Set, presumably as it was intended to be danced to that same music.

- First Quadrille consisting of Le Pantalon, L'Ete, La Poule, La Trenise, La Finale. These are the iconic First Set of Quadrilles that became popular across Britain from around 1816.

- Le Garcon Volage. This Quadrille shares a name with one of the Sixdrilles, it is evidently the dance from which the Sixdrille arrangement is derived. It's a relatively ordinary Quadrille dance seemingly unrelated (except by title) with the c.1816 dance of the same name by Edward Payne.

- Lodoiska. This Quadrille is essentially the same as the Finale Quadrille of the same name from Edward Payne's 1816 3rd Set of Quadrilles. This arrangement differs only in having the ladies act first in one of the figures, followed by the men, whereas Payne had the men act first followed by the ladies.

- Les Lanciers. This Quadrille is the Finale to The Lancers, the figures to most of which appeared earlier in the book. It's not exactly as originally published by Duval in Dublin in 1817, but a fairly close derivation.

- Second Quadrille consisting of La Portugaise, La Bonne Amie, La Paris, Le Wellington, La Pastourelle, La Finale. These are the figures to the c.1817 Second Set, A New Selection of Quadrilles, Waltzes and Spanish Country Dances published in Edinburgh by Robert Purdie and Performed by Mr Gow and his Band, and taught by all the Academys of Messrs Dun's, Smart, Ritchie & Strathy. That is to say, this set of Quadrilles were routinely played in Edinburgh in the late 1810s by Nathaniel Gow and his band, they were taught in the most prominent of Edinburgh's dance academys.

- Third Quadrille consisting of La Floride, La Valse En Cotillon, Les Graces, D'Egville Finale. These are the figures to the c.1817 Third Set, A New Selection of Quadrilles, Waltzes and Spanish Country Dances published in Edinburgh by Robert Purdie and Performed by Mr Gow and his Band, and taught by all the Academys of Messrs Dun's, Smart, & Ritchie. That is to say, this set of Quadrilles were routinely played in Edinburgh in the late 1810s by Nathaniel Gow and his band, they were taught in the most prominent of Edinburgh's dance academys (excluding, this time, that of Alexander Strathy).

- Fourth Quadrille consisting of La Nouvelle Paris, Le Carre, La Polonaise, La Vivacite, La Poulette - Finale. These are the figures to the c.1817 Fourth Set, A New Selection of Quadrilles, Waltzes and Spanish Country Dances published in Edinburgh by Robert Purdie and Performed by Mr Gow and his Band, and taught by all the Academys of Messrs Dun's, Smart, & Ritchie. That is to say, this set of Quadrilles were routinely played in Edinburgh in the late 1810s by Nathaniel Gow and his band, they were taught in the most prominent of Edinburgh's dance academys.

- English Quadrilles consisting of Petronelle, Italian Monfrina and Assembly Reel. These are reasonably ordinary Quadrille dances of unclear provenance.

- Spanish Dances consisting of The Guaracha and Petronelle. We've written about the Guaracha in a previous paper, the arrangement here is a little tricky to interpret.

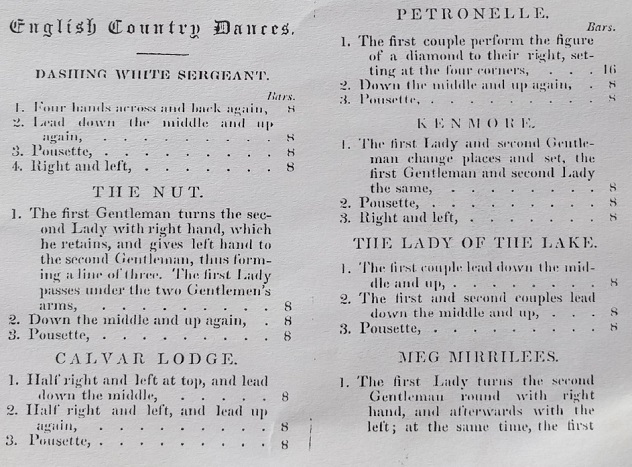

- English Country Dances consisting of Dashing White Sergeant, The Nut, Calvar Lodge, Petronelle, Kenore, The Lady of the Lake, Meg Mirrilees, Tom Thumb, John of Paris, Persian Dance, Jessie's Hornpipe, The Triumph. Most of these are reasonably well known, it curious that a specific choreography has been attached to them.

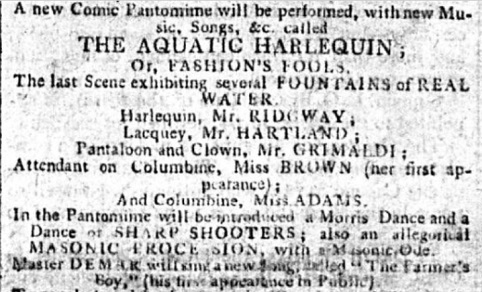

Figure 7. A Morris Dance was featured in the 1809 Aquatic Harlequin at Covent Garden ( The Sun, 1st of April 1809). Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive ( www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk).

- Scotch Country Dances consisting of Duke of Perth, or Keep the Country, Bonnie Lassie, Merry Lads of Ayr, Clyde Side Lasses, Lord McDonald's Reel, I'll Make You Be Fain to Follow Me, Mrs McLeod, I'll Gang Nae Mair to Yon Town, The Merry Dancers, Cammeronian Rant. Most of these are reasonably well known, it curious that a specific choreography has been attached to them.

Most of the dances within the book are relatively commonplace. The Les Lanciers Quadrille arranged for 12 dancers is unusual; the Sixdrilles were a little exotic though not unknown, the other dances in general are relatively unexciting. It's the Gymnastic Morris Dance, with Sticks which is highly unusual, I know of nothing similar published anywhere else in the world across the 1820s... or indeed at any other date within the entire 19th century! The collection as a whole is interesting from a modern perspective, it offers significant insight into what a Glasgow based dancing master of the late 1820s might teach to his pupils. It's the Morris dance that is especially exciting though. Sadly I know of no copies available to study on the internet at time of writing; there's a copy that's understood to be held in the archives of the RSCDS, and potentially a few others in private collections around the world, it's definitely a rare text! If you're lucky enough to own a copy, and you're willing to have it digitised and shared with the world, do please get in touch!

Morris Dancing in the Early 19th Century

Early 19th century Morris Dancing is a complicated subject to write about as there is little definitive information to work with, what is known with certainty reduces the further back in time we project. Something that was referred to as Morris Dancing had certainly become an active tradition in England by the early 19th century; to what extent that tradition was consistent across the nation, or consistent with that of earlier dates (or even of later dates) is difficult to discern. Little was written down. That which was written is often fragmentary, contradictory, or of unreliable provenance. The dancing masters of the period rarely even alluded to Morris Dancing, let alone wrote about it; Morris wasn't a discipline that the public expected their dancing masters to teach them. Some antiquarians of the later 19th Century, notably Cecil Sharp (1859-1924), interviewed older Morris Dancers about their memories of Morris dating back beyond the 1850s, those records do offer important clues. I myself am no expert on Morris, ancient or modern; the best source of information I've found is an excellent 2023 book by Michael Heaney titled The Ancient English Morris Dance (available from all good bookshops!), I can very much recommend that book if you'd like to read more. Indeed, I'm very much indebted to Michael for reading through this paper and helping me to avoid some mistakes (any that remain are of course my own!).

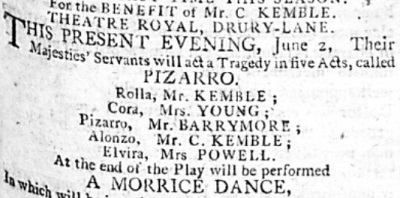

Figure 8. A Morrice Dance was featured in the 1802 Pizarro at the Theatre Royal ( The True Briton, 2nd of June 1802). Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive ( www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk).

One thing we do know of the early 19th century is that the concept of a Morris Dancer was sufficiently well established that attendees at Masquerade Balls might dress as one. For example, we've previously written of a Masquerade Ball held in 1800 by Mrs Walker at which Mr Thos. Sheridan cut some neat capers as a morris dancer (Staffordshire Advertiser, 31st of May 1800). Mrs Thellusson hosted another Masquerade in 1804 at which Mr and Mrs Shaftoe attended as Morrice Dancers (General Evening Post, 2nd of June 1804), Mrs Dupre hosted a similar event in 1805 at which Mr James attended as a Morrice Dancer (Morning Post, 17th of May 1805), Mrs Richards hosted a Masqued Ball in 1809 at which Mr Hornby attended as a Morrice Dancer (Morning Post, 14th of June 1809). The Morris Dancer seems to have been one of the stock characters that were considered suitable for this type of event. As a side note, you can read of these same references in Mike Heaney's excellent book, along with many other references to Morris from the period.

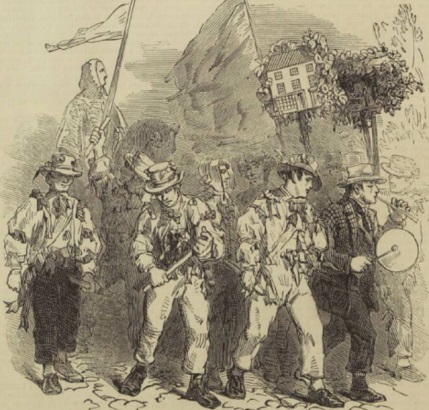

Some of the early 19th century dictionaries offer clues as to what the expected costume of a Morris Dancer would have been. The 1810 edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica offered of the Morrice Dance that it is a dance of young men in their shirts, with bells at their feet, and ribands of various colours tied round their arms and slung across their shoulders . It added: There are few country places in England where the morrice-dance is not known . The 1823 Dictionary of the Turf claimed that it differs from the contra-dance, reel, and waltz &c. inasmuch as men only perform the morrice-dance, having bells attached to the arms, knees, &c. . Whilst on the subject of dictionaries, the 1842 Universal Dictionary of Musical Terms offered that Morris is an old military dance, accompanied by the gingling of bells and the clashing of swords . Morris performers no doubt wore whatever they wanted to wear, the public expectation was that this would involve bells and ribbons, perhaps even handkerchieves tied about the person. The dictionaries affirm that most morris dancers were male, that morris was common to rural communities, and that some performers used swords (presumably wooden sticks) in their dances, perhaps lending the dance a martial air.

Figure 9. Morris Dancers at Lichfield, from the Illustrated London News for the 25 of May 1850. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive ( www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk).

Pinning down exactly what a Morris Dance was is a challenge. The newspapers and magazines offer a sampling of random references across numerous different contexts (and decades). For example, the Morning Chronicle newspaper for the 21st of August 1805 wrote of an entertainment given at Stowe involving several parties of Young Ladies from the boarding schools in the vicinity, who were dressed as morrice dancers, with tambourines and castanets. Their performances were inimitable, and the dancing was uncommonly graceful and elegant . The Day newspaper for the 16th of June 1809 wrote of a Masquerade at which Of the characters most deserving of praise for having contributed to the general stock of pleasantry were a groupe of Morrice Dancers, who went through a variety of most pleasing and difficult figures with great correctness and spirit. . Both of these examples involved polished performances, we also find references to village celebrations. For example, at Harleston's 1814 peace celebrations the return of the procession, was welcomed by Morris-dancers and children strewing flowers before them, the simplicity of which had an imposing effect . Village dance references often make reference to May Poles , May Games , Whitsun-Ales , Rush Carts , Hobby Horses and refer to Morris as The Ancient Dance . Morris was widely associated with pastoral fantasies of Merrie Olde England . Many dozens more such references could be offered but they tend to add little technical detail. Most such references are fleeting and unspecific. Readers were expected to know what Morris was, or at least to imagine that they knew what Morris was; they didn't need to be informed, Morris could simply be mentioned in passing to evoke thoughts of ancient English pastoral traditions.

There was another important context in which Morris Dancing could be experienced, that being the theatrical stage. There were many pantomimes and harlequinades that might feature a Morris dance as part of the entertainment (see for example Figures 7 and 8 for two such playbills). One such performance was the 1806 production of Harlequin and Mother Goose at the Theatre Royal in London, it featured (according to an 1862 description of the production in The Saturday Review) a Morris Dance in the seventh scene; this is of direct relevance as our Mons Bologna not only performed in this production, he was credited in the playbills as having been the choreographer (The Sun, 27th of December 1806). Likewise, the 1816 production of Harlequin and the Sylph of the Oak; or, the Blind Beggar of Bethnal Green featured a character named Tom Wilford who was played by our Mr Bologna and who was described as being one of the Morrice dancers to the Queen (Morning Chronicle, 27th of December 1816); it's no great stretch of the imagination to think that this production would also involve theatrical morris dancing. There were many other examples, these two are of particular interest as our Jack Bologna was personally involved with them both. It's possible that the 1827 Morris Dance that we have found published in Glasgow by Mons Boulogne was originally used in one of these productions, or some other of a similar nature. That observation leads us to an inevitable question however: to what extent was a stage performance of a Morris Dance the same as a genuine vernacular Morris Dance? Would such a dance be recognisable as the real thing ? Ultimately it's not possible to answer this question; they may have been perfected caricatures, they may have been entirely genuine, they may have been fantastical inventions of the choreographer. Whatever the case, it's likely that such stage performances of Morris would have affected the public perception of the art, sufficiently so that other performers might go on to adopt new conventions from the stage. Morris was an evolving tradition, it was revived several times over the centuries, each generation had the opportunity to help reinvent it. People have always used technical words to mean whatever they wanted them to mean; if a stage production featured something that was referred to as a Morris Dance , then that's what it was. Or at least, that's what enough people would have thought that it was that the difference becomes difficult to discern retrospectively.

In all probability our Morris Dance from Mons Boulogne's book was a theatrical Morris Dance collected from the London stage. It may have been choreographed by Jack Bologna himself for a London production, perhaps even the iconic and celebrated Mother Goose production of 1806. If so, it was employed in a rural scene of village life. To what extent it adopted genuine Morris technique of the period is impossible to know; in so far as it self referentially refers to itself as a Morris Dance , that's what we must consider it to be. And therefore, to the best of my knowledge, it is the very first published choreography that is explicitly of a Morris dance (rather than a regular Country Dance with a title that merely alludes to Morris in some way). It is a peculiar irony that such an important English dance survives in a book that was only published in Scotland!

Boulogne's Gymnastic Morris Dance with Sticks , 1827

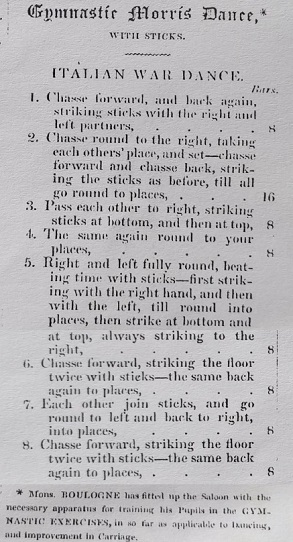

The Gymnastic Morris Dance, with Sticks (see Figure 12) was subtitled as Italian War Dance (which could have been the name of the tune associated with the dance). It was also accompanied by a footnote reading: Mons. Boulogne has fitted up the Saloon with the necessary apparatus for training his Pupils in the Gymnastic Exercises, in so far as applicable to Dancing, and improvement in Carriage . Several observations immediately come to mind from this. Firstly, the dance involves use of sticks ; secondly, it is in some sense a gymnastic dance, and thirdly it has some connection to the phrase Italian War Dance . We'll consider these points in turn.

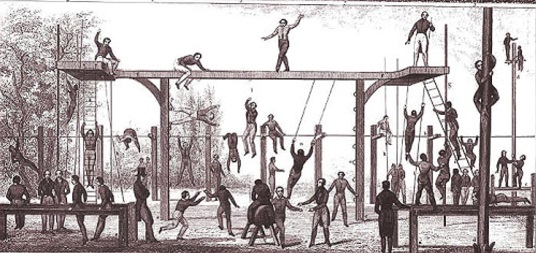

Figure 10. Friedrich Ludwig Jahn's original 1811 gymnastic Turnplatz in Hasenheide, near Berlin. Image courtesy of the Sokol Museum.

Let us first consider the issue of the sticks . Sticks in Morris Dancing were one of the pieces of equipment sometimes, though not universally, associated with the dance. The 1814 British Bibliographer by Brydges & Haslewood wrote of some c.1774 Morris Dancing near Oxford that: There were also the dancers of the Bedlam Morris. They did not wear bells, and were distinguished by high peaked caps (such as are worn by clowns in pantomimes) adorned with ribbons. Each carried a stick about two feet long, which they used with various gestulation during the dance, and at intervals struck them against each other. A clown and piper attended them. . The batons could evidently have been about two feet long. This particular performance described the dancers as being dressing in a similar fashion to pantomime clowns, also as being accompanied by a clown. It's perhaps notable that as a professional Harlequin Jack Bologna would often have performed on stage alongside a clown, in many cases played by his friend Joseph Grimaldi (1778-1837) (see for example Figure 3). It's possible that a Morris performance involving clown iconography may have been of particular interest to him, sticks may have been an important part of the associated performance. It seems likely that the performers in our dance each carried a single such baton, though this isn't entirely clear from the instructions (which we'll come to shortly), a case could be made for each dancer wielding two such sticks.

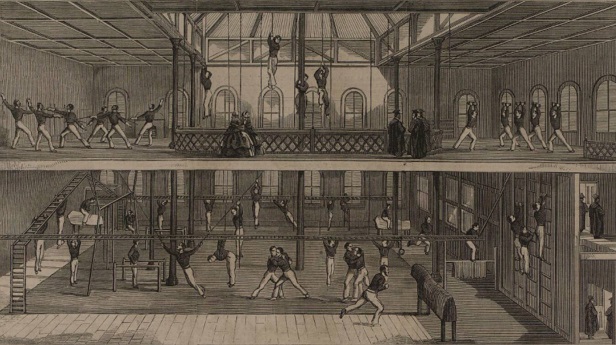

The 1820s saw significant interest in organised Gymnastic Exercises in Britain. An essay on the subject was published in the Morning Post newspaper for the 27th of May 1824; it commented that while the English had always enjoyed sports, there had been little interest in gymnastics prior to 1822. But since then large schools, together with both the army and navy, had begun adopting gymnastic exercises under a pattern promoted by Captain Phokion Heinrich Clias (1782-1854) (who in turn had learned the techniques in Switzerland, based on ideas promoted in Germany by Johann GutsMuths (1759-1839) & Friedrich Jahn (1778-1852), see also Figure 10). The Duke of Wellington was impressed with the concept and promoted it further, an organised programme of public exercise was found to be a healthy activity. Newspaper references to Gymnastics , and thereafter to Callisthenics , abound in the subsequent years. Our J.P. Boulogne evidently considered himself to be one of the first people to bring Gymnastic exercise to Scotland, along with some specialised equipment associated with it (perhaps similar to that seen in Figure 11); he thought it could help dancers by offering them an improvement in carriage . It's not clear why our Morris Dance was described as being a Gymnastic dance; in so far as it offered what may have been a healthy cardio-vascular workout to a group of men, perhaps it was seen as an intermediary discipline somewhere between ballroom dancing and pure Gymnastic exercise. Something that hinted at the military exercises that Captain Clias had introduced in his role as Superintendent of Gymnastics at the Royal Military College from 1823, yet that a dancing master could finesse. The use of sticks may have offered a hint of masculine activity to the dance, while also hinting at the patriotic Merrie Olde England associations of the Morris Dance.

Figure 11. The Oxford Gymnasium from the Illustrated London News, 5th November 1859. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive ( www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk).

The phrase Italian War Dance appears below the title of Gymnastic Morris Dance within the publication. The typesetting, as compared to other pages within the book, hints that it's the name of the specific tune or dance within the general category of Morris Dances (eg as La Floride is a specific Quadrille within the Third Quadrille of Figure 6). But as there is only one Morris dance presented, this isn't certain to be the case. Moreover, I'm not aware of any published tunes under the name Italian War Dance that the name may allude to. The subtitle could instead imply that all Morris Dances were considered to be Italian War Dances . This theory is plausible; the nineteenth century antiquarians who wrote about Morris tended to consider it a militant Dance, for example the 1842 dictionary quoted above defined it as an old military dance . In so far as it was usually danced by men, and could involve the use of sticks, an ancient military context was a reasonable assumption. Dance writers of the early 19th century imagined a continuous progression of dance innovation from the Greco-Latin classical sources through to the modern era, with modern civilisation derived from that of the Romans. Defining Morris as being derived from primitive Italian sources would lend itself to such an interpretation. Indeed, modern scholarship does link the origins of Morris to Italian precursors, the name could indeed have been intended as an explanatory subtitle.

We should also consider the question of whether this Morris Dance, printed in 1827 in a Ballroom manual, was actually being danced by the public. I know of no evidence of it having been danced, though it might well have been. Presumably our Mons Boulogne was teaching it in his academy, and as he'd purchased equipment for tuition in Gymnastics, there must have been some interest in a Gymnastic dance. As best as I can discern, this particular dance was simply an oddity that he decided to include in his book because he could do so, it probably wasn't danced outside of his academy and didn't trigger a new localised tradition in the Glasgow area. It's just one of those curious anomalies that make life interesting!

Choreographed Figures for the Gymnastic Morris Dance with Sticks , 1827

Returning to the subject of the dance itself, several further observations need to be made before we can consider how to perform it. Firstly, the figures for the dance do not employ modern Morris Dancing terminology. They are instead written using the vocabulary of ballroom dancing of the time. Secondly, the starting formation of the dancers isn't given; an argument could be made for two parallel lines, or for two concentric circles, or for a single circle or square. My best guess is that a square of eight dancers is intended, much like that of a Quadrille dance, two dancers per side of the square. It's an important point as the interpretation of the dance can vary wildly depending on how we visualise the dancers starting. In so far as this dance was published alongside a group of other square dances, the square formation seems likely. The dancers themselves would presumably have been male, or at least same-gender, each carrying a baton or stick. It occurs to me as possible that the dance could be performed around a maypole; I'm not suggesting that actually happened, just that the figures do allow for that possibility.

It's also worth noting that the instructions are confusing. At times they seem to be written for couples, as in a ballroom social dance (for example by referring to partners ); at times they seem aimed at lead individuals (an instruction might involve turning to the right, yet the implication is that someone else must turn to the left). This makes visualising the dance that much more complicated. This problem isn't unique to this dance, anyone who interprets historical social dance will be familiar with the issue; but not knowing the starting formation of the dance adds complexity, we have to guess a little more than would otherwise be the case. The dance itself is 72 bars in duration as written, though our interpretation of it suggests 80 bars. There's no hint as to a tune to use, or the tempo to dance to. Presumably the dance could be repeated as many times as is felt appropriate for sufficient gymnastic exercise to be achieved.

What follows is a suggested arrangement of the dance that I've come up with, other arrangements are also conceivable. This arrangement is for 8 Dancers in the form of a square, 2 dancers per side of the square; each dancer holds one stick each. The dance begins with everyone stood as though forming up for a Quadrille dance. We've described the Chasse step on our steps page, along with a video of it being performed. The text in bold is as given by Mons. Boulogne (see also Figure 12), the explanatory notes below are our suggested arrangement of the figures. Once again I'd like to thank Michael Heaney for his contributions to this arrangement; any errors are once again my own, our fruitful discussions over it have helped to shape my own thoughts on the dance however.

Figure 12. Mons. Boulogne's 1827 Gymnastic Morris Dance, with Sticks.

Number

of

Bars | Boulogne's Notation

(with explanatory notes) |

|---|

| 8 |

Chasse forward, and back again, striking sticks with the right and left partners.

All eight dancers dance forward (2 bars) and back (2 bars). Partners (the dancers on the same side of the square) then turn to face each other, some turning right and some turning left as the case may be, and strike sticks (2 bars); everyone then turns to face the opposite direction, meeting someone else on the corner and strike sticks with them (2 bars).

|

| 16 |

Chasse round to the right, taking each others' place, and set; chasse forward and chasse back, striking the sticks as before, till all go round to places.

All eight dancers face right and dance around a circle into opposite places from where they started (2 bars), all eight dancers Set on the spot (2 bars). All eight dancers repeat the first 8 bars of activity (8 bars). All eight dancers turn again to the right and dance around a circle to return home (2 bars) and Set on the spot (2 bars).

|

| 8 |

Pass each other to right, striking sticks at bottom, and then at top.

Partners on each side of the square turn to face each other, then chain their way half way around a circle to opposite places; this involves passing four people, strike sticks while passing each of those people, first with a low strike and then with a high strike (2 bars per transition, 8 in total).

|

| 8 |

The same again round to your places.

Repeat the preceding 8 bars so that everyone returns to their home position.

|

8

(or 16?) |

Right and left fully round, beating time with sticks; first striking with the right hand, and then with the left, till round into places, then strike at bottom and at top, always striking to the right.

This instruction is particularly confusing. It appears to involve a similar movement to that of the previous 16 bars, but in half the time. The term Right and Left might be interpreted as a Chaine Anglaise in Quadrille dancing, where the head couples exchange places, followed by the side couples. Whereas our arrangement suggests a rapid chaining of the set, as in the preceding 16 bars, but with only 1 bar per transition (8 total). Dancers should strike sticks with each person they meet, first on the right and then on the left, ending back where they started (this should be a gymnastic exercise after all). Then repeat the chaining a second time, for a further 8 bars (16 total), this time striking at bottom and top with each person they meet.

|

| 8 |

Chasse forward, striking the floor twice with sticks; the same back again to places.

All eight dancers dance forward (2 bars) and strike the floor twice with sticks (2 bars). Then return (2 bars) and strike the floor twice with sticks (2 bars).

|

| 8 |

Each other join sticks, and go round to left and back to right, into places.

All eight dancers hold their stick out to the right, and with their left hand grasp the stick of the person to their left; all eight slip the circle round to the left (4 bars) then back again to the right (4 bars).

|

| 8 |

Chasse forward, striking the floor twice with sticks; the same back again to places.

All eight dancers dance forward (2 bars) and strike the floor twice with sticks (2 bars). Then return (2 bars) and strike the floor twice with sticks (2 bars).

|

The instructions may be difficult to visualise, we've animated our suggested arrangement of the dance here. Finding a tune to suit the dance may be a little interesting; it would ideally begin with a repeated 12 bar opening phrase; then an 8 bar repeated phrase, then another 8 bar repeated phrase, then three more 8 bar phrases. Other arrangements of the music are also possible, a single 8 bar phrase used throughout might be made to work. Music selection is left as an exercise for the reader!

I know of no recreations of this dance to-date in the modern era; if you attempt to recreate it, do please capture a video and let us know about it!

Conclusion

Morris Dancing was an active tradition in England across the late 18th and early 19th centuries, unfortunately there are few concrete clues as to how such dances were actually performed. It's likely that many different traditions existed concurrently. Mons. Boulogne's Gymnastic Morris Dance is a rare (and probably unique) example of a choreographed Morris dance to have been published, it offers an exciting glimpse into one such Morris tradition of the early 19th century. It was likely a stage dance rather than something performed in the villages, yet it could be representative of the type of Morris dancing that was genuinely being performed around the country. It is a fascinating relic of the past!

And it's at this point that we'll leave the investigation. If you have any further information to share, do please Contact Us as we'd love to know more.

|