| Return to Index |

|

Paper 20 Regency Era Country Dances - EmbellishmentsContributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 22nd January 2016, Last Changed - 21st June 2025]If you're reading this paper it's likely that you've read our previous research papers on the Regency era Country Dancing Industry, the Figures, the Music, and the Form of the Country Dance. If not, you might like to do so. In this paper we'll consider those graceful embellishments to a Country Dance that marked the difference between a regular Country Dancer, and an elite dancer. Many social dancers 200 years ago did not reach this level of accomplishment, they were happy just to dance and to enjoy themselves; but the best dancers mastered the etiquette, steps and courteous attentions taught by the dancing masters themselves.  Figure 1. Wilson's 1821 The Address, Payne's 1814 A New Companion to the Ball Room, and Cherry's c.1813 A Treatise on the Art of Dancing

Figure 1. Wilson's 1821 The Address, Payne's 1814 A New Companion to the Ball Room, and Cherry's c.1813 A Treatise on the Art of Dancing

Any investigation into style and technique will necessarily be limited; these ornaments to social dancing did not conform to strict rules, conventions could vary over time or by context; the advice that follows is suitable for London in the Regency period, but it shouldn't be seen as definitive or exhaustive. If you're investigating the topics for yourself, you're likely to find advice elsewhere that doesn't precisely match what's written about here - the conventions varied. This paper will concentrate on advise for Country Dancing, but in many cases it will apply equally to other social dancing forms of the same era, such as Quadrille dancing. In this paper the references to John Cherry refer to his c.1813 A Treatise on the Art of Dancing in the Ball Room, a reference to Thomas Wilson refers to his 1821 The Address, unless otherwise noted, and a reference to Edward Payne is to his 1814 A New Companion to the Ball Room (see Figure 1).

Note: this paper is part of a series on Country Dancing. The full collection consists of:

Honours, Bows, Curtseys and Salutes

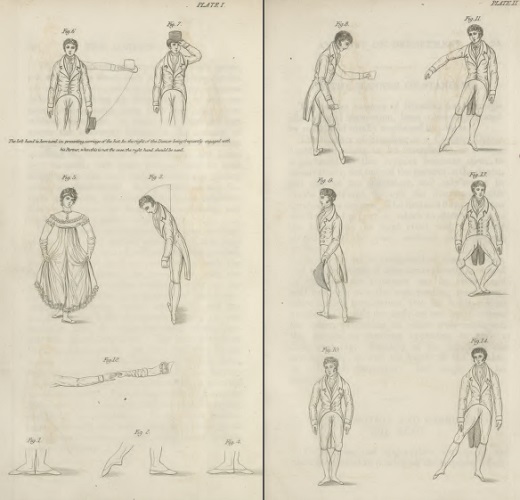

We've previously written about the Courteous Start that was generally used in Country Dancing of the Regency era, where the dancers in a longways set progressively enter the dancing as the first couple reach them. That convention is quite different to how historical Country Dances tend to be danced today; a modern recreation of a historical Country Dance will usually begin with four or eight bars of music in which the couples  Figure 2. Image plates from Wilson's 1821 The Address

Figure 2. Image plates from Wilson's 1821 The Address

Several Country Dancing guides of the 1810s refer to the first strain of a tune being played once through before the dancing begins. For example, Payne wrote in 1814:

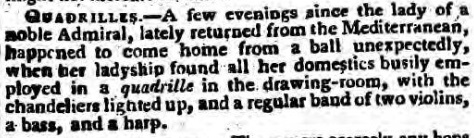

The Quadrille dance became enormously successful in London from around 1816. It emphasised the need for honours - the first eight bars of music were explicitly used for honouring one's partner, the dancing began with the second eight bars. Most of the Quadrille guides refer to this convention. In so doing they hint that this was a novelty, not something widely known from the other social dances of the era. One social commentator (published in Knights Quarterly Magazine Volume 1, 1823) wrote of the quadrille that

The earlier Cotillion dance form, at least when first introduced to England in the 1760s, also featured the convention of

The Regency era Country Dance, as practised at the Assembly Rooms, was arranged so as to honour the lead couple as they danced down the set. Each new couple that was drawn into the dance might acknowledge the lead couple with a small bow or curtsey before joining in. Bows and Curtseys were also used elsewhere in a Country Dance. Cherry (page 73) records that:

It's not clear whether the custom of honouring one's partner was a standard commencement to the English Country Dance in the 18th Century. Some 17th century Country Dance choreographies did include an explicit honouring figure at the commencement, and potentially also on each iteration of the Country Dance. An interesting essay by Kate Van Winkle Keller investigates such calls as

Performing the Honours

Wilson (page 16) described the The gentleman, in making the Bow, will observe that his right or left foot, according to the situation in which he may become placed, should be passed from the first position shewn by Fig.1 Pl.1 into the second, shewn by Fig.2, the first position, should then be resumed; the knees preserved straight, and the head and shoulders gently inclined, tracing forwardly an imaginary curved or bowed line, and returning to an upright posture in the same gradual and easy manner; making no rest during the inclination of the head (see Fig.3. Plate 1.)

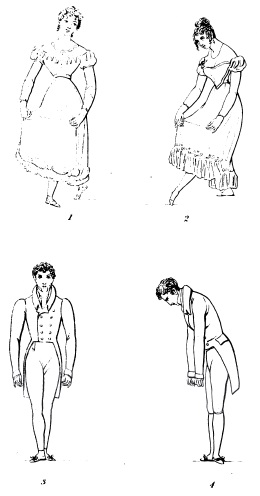

Wilson also described the curtsey. He first described bad curtseys (page 18); some ladies  Figure 3. How to Curtsey and Bow, Carlo Blasis, 1829

Figure 3. How to Curtsey and Bow, Carlo Blasis, 1829

The lady in making the Courtesy, should pass her foot from the third position, (shewn by Fig. 4.) into the second position, and bring it to the fourth position in front, gently sinking with the knees turned outwards to the sides; preventing, as much as possible, any forward projection of them (see Fig. 5.); an attention to which will afford an easy equilibrium of the figure, so necessary to the graceful effect, capable of being produced, and most properly required.

Cherry (page 72) emphasised that

Standing with Style, and Polite Attentiveness

The dancers in a Country Dance may spend quite a long time The manner of Standing in a Country Dance ought particularly to be attended to, as a loose deportment in this respect becomes open to observations, not only of the persons in the dance, but also of the spectators, and only serves to create contempt through the disrespect such carelessness evinces. The first and third positions are the most proper in which to stand easily, as the body may be kept erect with a suitable elevation of the head, without any apparent stiffness.

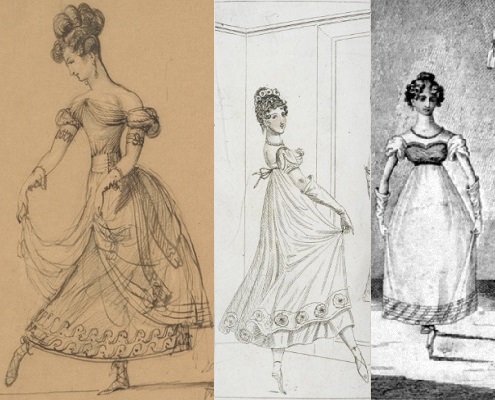

Cherry (page 72) wrote:  Figure 4. Examples of elegance, from Sir George Hayter's 1824 A Minuet (left), the anonymous 1818 Le Maitre A Danser (centre), and Alexander Strathy's 1822 Elements of the Art of Dancing (right).

Figure 4. Examples of elegance, from Sir George Hayter's 1824 A Minuet (left), the anonymous 1818 Le Maitre A Danser (centre), and Alexander Strathy's 1822 Elements of the Art of Dancing (right).

The embellishments bestowed on the performance of figures, must be drawn from those acquirements in due proportion, particularly that of bowing, which while standing in or coming down a country dance, is much required by ladies and gentleman; as an inclination of the head should always accompany the giving a hand to another person, - an inclination certainly not ammounting to a bow, but bearing a graceful resemblance of one, and should be varied in its extent to various occasions. Great care should likewise be bestowed on the position in which a person stands in a country dance, while not engaged in a figure, and the position should be varied at different intervals, though in general it should be elegantly upright.

The need to acknowledge other dancers within a Country Dance is something Barclay Dun mentioned in his 1818 A Translation of Nine of the Most Fashionable Quadrilles: Edward Payne (page 19) wrote a passage in his book that described some particularly impolite activities that can occur in a Country Dance; one example involved those who were stood out talking to each other, rather than remaining politely attentive to the dancing. The passage reads: The impolite manner of the couple going down the dance, gaining the bottom, and then abruptly leaving the room is too frequently practised; but, seldom or ever by persons of good breeding. ... I must likewise inform such Gentlemen, who are continually in conversation with each other, or with their partners, they should observe their ill manners and carelessness, as it is the means of greatly annoying the couples going down the dance, and others in not being ready to join in the figure therefore, they cannot but suppose they are remarked by the company, as not being the most agreeable persons to dance with.

W. Smyth, writing in his 1830 Pocket Companion for Young Ladies and Gentlemen (second edition), continued to promote a polite awareness when standing. He wrote:

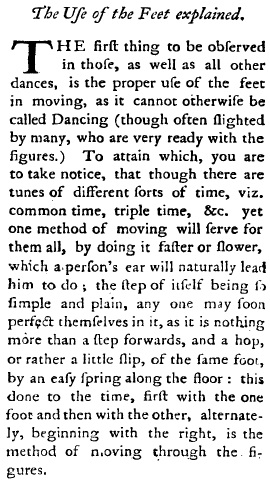

Country Dancing StepsCountry Dancers two hundred years ago did dance, they didn't walk through the dances as sometimes happens today. The anonymous A.D. dancing master wrote in the 1764 Country Dancing Made Plain and Easy that a simple step-hop sequence was appropriate in all Country Dances of his period (page 13, see Figure 5): The first thing to be observed in those, as well as all other dances, is the proper use of the feet in moving, as it cannot otherwise be called Dancing (though often slighted by many, who are very ready with the figures.) To attain which, you are to take notice, that though there are tunes of different sorts of time, viz. common time, triple time, &c. yet one method of moving will serve them all, by doing it faster or slower, which a person's ear will naturally lead him to do; the step of itself being so simple and plain, and one may soon perfect themselves in it, as it is nothing more than a step forwards, and a hop, or rather a little slip, of the same foot, by an easy spring along the floor: this done to the time, first with the one foot and then with the other, alternately, beginning with the right, is the method of moving through the figures.  Figure 5. The Use of the Feet explained, from the 1764 Country Dancing Made Plain and Easy by A.D.

Figure 5. The Use of the Feet explained, from the 1764 Country Dancing Made Plain and Easy by A.D.

He also went on to describe a

This basic It's clear that a vocabulary for Country Dancing steps had emerged by the start of the 19th Century, a vocabulary that seems not to have been widely known just 20 or 30 years earlier. A challenge in rediscovering these steps is that not many writers described them. Cherry didn't attempt to do so individually, he wrote that (page 9): The steps in country dancing should be appropriate to the figure - side steps for side figures, forward steps for forward figures, and so on, of which there are great variety; and further, it is better to know many steps besides what are made use of in country dancing, in order that those used may be executed with superior judgement; and it will always be observed, that those who are acquainted with hornpipes, minuets, and other fancy dances, considerably surpass, in gracefulness of style, those who have not such advantages. He did offer some practical advice (page 75): Shuffling, or other noisy steps, are improper for country dancing, as they look vulgar, and destroy the effect of the music. Payne promoted simplicity. He wrote (page 19):  Figure 6. The five positions, from S.J. Gardiner's 1786 A Definition of Minuet-Dancing

Figure 6. The five positions, from S.J. Gardiner's 1786 A Definition of Minuet-Dancing

The more simple the steps used in a country dance, the more beautiful and pleasing they appear; a free, easy, graceful bending of the instep combines an elegant air with the execution of the steps, which should be performed with a certain pliancy in the limbs, devoid of all design or study - many persons attempt to make use of difficult steps, without having a correct notion of their proper form; others again, depend on their agility, such as in cutting capers; brilliant cutting and surprising steps, may do to shew off some dancing master &c. at certain times, but rest assured, never characterises the Gentleman. Wilson provided further advice (page 28, image references are to Figure 2): The Steps are composed for the correct performance of the various figures to the times and measure or music thereto adapted; it is contrary to correct Deportment when they are not properly applied.

Wilson's reference to Hornpipe steps being unsuitable is particularly interesting as, around 85 years earlier, a dancing master called Benjamin Towle (author of the 1759 Universal Dancing Master) explicitly wrote that

Wilson's most complete information regarding steps can be found in his 1820 Complete System of English Country Dancing, he didn't write much about performing them but he did suggest the steps to use with each of his figures. For example, his Foot in the centre was described as involving an:

A Scottish influence in country dancing was fashionable amongst elite dancers of the early 19th century. A commentator in the Dublin Evening Packet and Correspondent newspaper for the 3rd April 1834 (in turn quoting from the Court Journal of a slightly earlier date) complained of Princess Charlotte's Scottish dancing master of the late 1800s that:

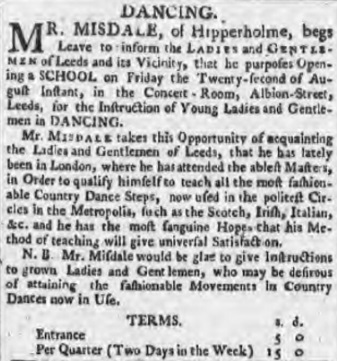

Two early 19th century books offer particularly significant advice for dance steps. One of these documents was F.J. Lambert's 1815 Treatise on Dancing, the other is Francis Peacock's 1805 Sketches on the Practice of Dancing. We've written more of Lambert elsewhere, you might like to follow the link. Peacock wrote of the popular Scottish steps including the Minor Kemkóssy There was, however, a backlash. The author of the 1811 Mirror of the Graces, an etiquette guide for young ladies, advised against the use of fancy balletic steps in social dances (foreshadowing the similar advice from Edward Payne quoted above):  Figure 7. Advertisement for Mr Misdale, from the Leeds Intelligencer, 18th August 1800. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Figure 7. Advertisement for Mr Misdale, from the Leeds Intelligencer, 18th August 1800. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Theseballetdances are, we now see, generally attempted. I sayattempted, for not one young woman in five hundred can, from the very nature of the thing, after all her study, perform them better than could be done any day by the commonestfiguranteon the stage. We all know, that, to be a fine opera-dancer, requires unremitting practice, and a certain disciplining of the limbs, which hardly any private gentlewoman would consent to undergo. Hence, ladies can never hope to arrive at any comparison with even the poorest public professor of the art; and therefore, to attempt the extravagancies of it, is as absurd as it is indelicate.

But conversely, the anonymous A Gentleman who wrote the 1823 Etiquette of the Ball-Room thought adapting fancy Quadrille steps to Country Dancing was entirely appropriate:

There was clearly a disparity amongst the Regency era dancing community. Some promoted naive simplicity in Country Dancing, some promoted a range of balletic and baroque inspired steps, others were somewhere between the extremes. An observation I'll add is that none of the sources suggest that the entire assembly would dance using the same steps within a single dance. The advice of the dancing masters was aimed at the individual and their responsibility to the rest of the assembly; each dancer within a longways set might conceivably have been dancing with different steps, even though the figures were shared. Country Dances weren't performance pieces, ordinary dancers weren't trained to If you're interested in the steps for other social dances of the period, various writers discuss them. S.J. Gardiner described the Minuet steps in his 1786 A Definition of Minuet Dancing. Wilson described the principle Waltz steps in his 1816 Correct Method of Waltzing. Payne described the principle steps for French Quadrille dancing in his 1818 Quadrille Dancer, and went on to describe the Waltz and Promenade steps in the same work as applied to Spanish Country Dances. Peacock described numerous Scottish steps in his 1805 Sketches on the Practice of Dancing, Alexander Strathy described the steps for Quadrille dancing in his 1822 Elements of the Art of Dancing and F.J. Lambert's 1815 Treatise on Dancing described the French steps in some detail. Readers might also enjoy the videos of Steps hosted here at RegencyDances.org, these videos focus on the principal steps used within the modern Regency dancing movement.

Grace and Elegance in Country Dancing

Knowing the basics of Country Dancing wasn't sufficient to be considered a finished dancer, one must also dance gracefully. Wilson (page 8) wrote:

An important aspect of graceful dancing involved an awareness of smooth motion. The dancing masters encouraged  Figure 8. Hogarth's engraving of a Country Dance 1753. Plate 2 from The Analysis of Beauty. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 8. Hogarth's engraving of a Country Dance 1753. Plate 2 from The Analysis of Beauty. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

When the hand or hands are to be presented to another person, straight lines and angles in the presentation must be carefully avoided; it should likewise be done in the most gentle and attentive manner, touching or bearing as lightly on such person as possible, and never holding a hand fast or in the least resembling it. After the hands are joined, if one from each person, the two hands so joined together, with the arms, should form a serpentine line, for which reason the two persons should stand or dance at a convenient distance. If both hands of two persons are joined together, they, with the arms, should form an oval ... If the hands of four or more persons are joined ... [they] should form part of the ring alluded to by such figure, whereby all resemblance of a straight line or angle would be avoided. Payne (page 15) also wrote of the elegant use of the arms in Country Dancing: A graceful management of the arms and hands in Country Dancing cannot be dispensed with, to form a complete dancer, therefore, they should be strictly attended to. F.J. Lambert in his 1815 Treatise on Dancing wrote of the importance of elegant arm movements, rather than steps, when dancing Country Dances. He wrote: In the country dance the attention should be given more to the management of the arms than to the feet, because the ear will naturally adapt easy movements suitable to the tune; the only attention that is necessary with respect to the feet is, to have them well turned out and pointed, that they may not incommode those who are dancing, and to move them exactly in time with the music. It is not the feet that are looked at, it is the whole carriage; persons are distinguished by this for their genteel and elegant style. The hands across, which is a singular figure in itself, shews the management of the arms and head to great advantage. When you present the right hands, turn the head and look at the person to whom the hand is given, and observe the opposition of the arm to the head; the left arm is raised much higher than the right, and in giving the left hand raise the right in opposition to it. The effect is striking, but if the hand is carelessly given, without looking at the person, and the contrary arm is hanging down, the figure has no expression or effect, and the dancing is inelegant. Wilson (page 25, image references are to Figure 2) made similar suggestions, and added that one should take care that: ... whether one hand, or both be joined, they be not raised above the level of the shoulder; except the figure of the dance be such as to require it; ... The too frequent practice of moving the arms up and down, inLeading down the Middleis an extravagant impropriety, and disgraceful to those who use it in genteel company. Wilson also wrote about the motion of the head in dancing (page 24, image references are to Figure 2): According to the turns of the body, and movements of the feet, the Head should be moved in an easy, graceful manner, (see Fig. 11. Pl. 2.); a pleasant countenance contributes greatly to an improved effect, and takes away all appearance of labour, in performance of the several movements. The anonymous author of the 1811 The Mirror of the Graces offered the following general advice to ladies who dance: The body should always be poised with such ease, as to command a power of graceful undulation, in harmony with the motion of the limbs in the dance. Nothing is more ugly than a stiff body and neck, during this lively exercise. The general carriage should be elevated and light; the chest thrown out, the head easily erect, but flexible to move with every turn of the figure; and the limbs should be all braced and animated with the spirit of motion, which seems ready to bound through the very air. By this elasticity pervading the whole person, when the dancer moves off, her flexile shape will gracefully sway with the varied steps of her feet; and her arms, instead of hanging loosely by her side, or rising abruptly and squarely up, to take hands with her partner, will be raised in beautiful and harmonious unison and time with the music and the figure; and her whole person will thus exhibit, to the delighted eye, perfection in beauty, grace, and motion.

The deportment of the dancer, the elegance in motion and the graceful acknowledgement of other dancers were amongst the techniques the dancing masters would teach to their students, once the basics of Country Dancing were mastered. But as always, the style of the dancing had to be compatible with the music; Country Dances were often played at a rapid tempo, in which case there would be little opportunity to Formerly, before the introduction of Steps, it was customary to play every Air, whatever might be its character, in one time: namely, with the utmost rapidity, because the Dancers were at a loss what to do, either with their feet or themselves, if they were not in perpetual motion. But, since Dancing has become a Science, various Steps have been introduced, with a view to display the skill of the Dancer; and as these require more Time to perform them with elegance, it follows of course, that the Time in which they ought to be played will be considerably slower than before their invention. Talented dancers could display their skill with slower music. Wilson introduced his Waltz Country Dances to London in 1815, they were probably adapted to encourage a graceful display of elegant waltzing prowess, they may have been the perfected pinnacle of the English Country Dance in Regency London. Unfortunately the popularity of the Country Dance waned from this date; the choreographed Quadrille and risqué Waltz dances supplanted them in England's Assembly halls. An 1825 phrase book printed in Bruges captured some typical conversational fragments that might be heard in a Dancing Lesson, examples (pertaining to the need for elegance) include: Such phrases were presumably to be expected of a Dancing Master, and offer a brief glimpse into their tuition.Good morning Gentlemen, come put on your pumps.

Impolite Behaviour in a Country DanceThere are many records of inappropriate behaviour in dancing, contrary to the rules of etiquette, that were to be avoided. For example, most Assemblies had dropped the rules of strict precedence by social rank, but some dancers could still be rude to those they felt were inferior. The following text is from the 1824 Repository of the Arts, it describes a ball at aCountry Town: In that example the socially superior dancers showed their contempt through tossing their heads, averting their eyes, and through some blocking of the way... subtle irregularities that are horribly impolite, but still allow the dancing to continue. A similar example involving Royalty was reported on in 1827 by La Belle Assemblé:Next to the quadrille came the English country-dance, in modern language ycleped kitchen-dance, still kept up in country-towns for the accommodation of those who cannot dance quadrilles. A bride led down. She was in all the bloom of youth and beauty. It was evident that a deeper tint than usual suffused her cheek, and this was rendered still more apparent by the contrast of her dress. Yet no eyes but mine followed her as she sought her way modestly but gracefully down the scarce open ranks. On the contrary, I observed envious tosses of the head, aversion of the eyes, &c among the females, and even some unpoliteness on the part of the males in blocking up the way. I endeavoured to ascertain the cause of this. She was the apothecary's daughter, or in other words she wasnobody. The couple that followed were not so treated; they weresomebodies. Said I to myself, Was it so twenty years ago? At the ball in the evening, Colonel Lennox stood up, in a country dance, with Lady Catherine Barnard. The Prince of Wales, when he came to the Colonel's place in the dance, took the hand of his partner, the Princess Royal, just as she was about to be turned by the Colonel, and led her to the bottom of the dance. This snub was reported to be at a Ball in 1789, the result of a sense of righteous indignation following a duel. The Prince was part of the way through dancing down a Country Dance, but rather than dance with the Colonel when his turn came, the Prince led his partner directly to the bottom of the set. It was a very public rebuke. Edward Payne (page 16) wrote of a type of hop room dancer who could spoil the pleasure of an elegant dance: Such persons who have the manner of confining down the hands of their partners, their body bent forward, and elbows turned outwards, are termed hop room dancers; which vulgar method, is so different from the true Polite manner of Country-Dancing, that they are instantly distinguished; nothing can be more unpleasant in my opinion, to a Lady of Genteel carriage and manners, than to get a partner of such a description; and those who have practised this inelegant style of dancing, will take nearly the time they have been at it, to erase the habits from them. Mr Jenkins in his 1822 The Art of Dancing expanded on this behaviour, he wrote of several errors that frequently occur in Country Dancing: It is a common error with gentlemen, instead of lightly touching the hands of ladies, to hold them so fast, that they can scarcely disengage themselves, which is vulgar in the extreme, and destroys all appearence of ease in the performance. Payne also wrote of affectation in dancing, a most unpleasant vice (page 18): Looking at the feet while dancing, I know to be in some a bad habit only; but is chiefly practised by those possessed of the worse of vices in dancing, affectation, which I cannot pass over without cautioning the pupils, and every one, to be carefully guarded against; it is sure to deceive a person in the judgement of his own abilities; it is impossible to please by affectation, though in general he is misled by that erroneous Idea. Nothing defeats more that intention, than a vice that is incompatible with the graces, which dissapear at the least assumption of affectation. Such persons who are possessed of that false, finical, affected air, are always eager to display it; but they may rest assured that wherever it is seen, it is sure to offend and excite contempt.

Wilson (page 27) provided further examples of For instance, some persons may be observed in the ball room, who are excellent dancers, and consequently despise the efforts of others; and in going down a Country Dance, or standing in it as neutral, when they are required to Turn or Swing Corners, or take the hands inLeading Across,Setting and Changing Sides, &c. affectedly omit what is correct, and dance round the lady or gentleman, with whom they should turn as the figure requires. Also in Quadrilles, inChaine Angloise,&Chaines des Dames,the same will apply.  Figure 11. Domestic Antics, Salisbury and Winchester Journal, 16th June 1817. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Figure 11. Domestic Antics, Salisbury and Winchester Journal, 16th June 1817. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Francis Peacock in his 1805 Sketches on the Practice of Dancing made a similar statement: Cherry's advice was a little more oblique (page 71): Cherry went on to comment (page 77) that dancers should remain aware of their position in the dance at all times, and pay attention:Therefore, those persons who would dance in superior style, should attentively observe the line which is drawn between the manners of cultivated and genteel persons, and those of the untaught and vulgar part of society; and take care, that they always imitate the former, as well in trifling circumstances as in important ones, till their judgement is sufficiently matured, to enable them to exercise it at their own discretion, and be an example to others; but the most extreme caution is necessary in displaying the judgement in a ball room, for the errors of one evening may call forth such severity of criticism as may ever give place to painful reflection. Wilson had a particular distaste for indelicate activity within a dance (page 29):If all persons in a dance would pay this attention, dancing would look much more like an elegant and polite amusement than it frequently does; for what with calling out to some persons to mind the figure, pulling or pushing others into it, explaining it to others, and perhaps but few doing it correctly, a country dance too often appears like a confused assemblage of dancers, or an undefined maze, without beginning or end. The impropriety of snapping the Fingers in Reels, and using the sudden howl or yell, which partakes of the customs of barbarous nations, is directed to be avoided... such practices are entirely contrary to correct and genteel Deportment. The etiquette guides also provided lists of unacceptable behaviours to be avoided, in addition to the above, as did the bye-laws of the Assembly Rooms; but that's a subject we'll save for a future article. What is clear is that the accomplished dancer could be recognised as much by their polite attentions to the company as from their personal skill.

When one thinks of Regency era dancing, it's often this elite form of social dancing that comes to mind: careful steps, polite attentions, fluid grace, and furtive conversations away from the chaperone! But the Twelve Penny Hop, Lady Mayoress's Rout, Public Ball, Kitchen Dance and Country Ball were also part of the social dancing experience (see also Figure 11), and also part of Regency era dancing. Not everyone danced like the elite. So don't worry if as a reenactor of historic dances you struggle with the ornaments and embellishments of the advanced dancers, many people 200 years ago did so too. The Dancing-Masters wrote about the importance of deportment, but their livelihood came from convincing ordinary people that they weren't good enough! They also recorded that many dancers failed to achieve perfection. Even the most elite of dancing establishments would ring with laughter. The author of the anonymous Recollections of Almacks (Almack's being the most elite of Regency era Assembly Halls) wrote of Country Dancing:

Graceful politeness and deportment are important when recreating a Regency era Country Dance, but dancers aren't expected to perform with the precision of a military drill. Social dances are for ordinary people, and even the most elite of dancers will infuse a dance with their own personality and charm. It's clear that the dancing masters 200 years ago didn't share the same opinions on the minutiae of dance practice, the rigorous application of any single piece of historical advice is therefore problematic... so please, have fun with your dancing. The most important thing is to ensure that your partner, and the company in general, enjoy dancing with you. In the words of an 1828 commentator in The Companion: We'll leave this investigation here. If you know of further information regarding the finishing of the accomplished Regency era dancer, do please contact us, as we'd love to know more. You can also learn more about the dancing steps through our steps page.

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved