| Return to Index |

|

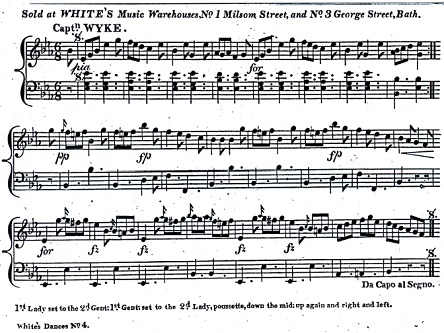

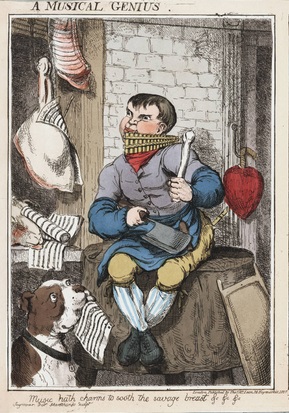

Paper 14 White v. Gerock, 1818(of Country Dances & Copyright)Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 3rd June 2015, Last Changed - 23rd March 2021]In this Paper we'll consider an interesting legal case in the history of English Country Dancing. It helped to establish how the British copyright laws applied to Country Dances, and reveals a number of interesting and otherwise poorly documented aspects of the Country Dancing industry. It's referred to as White v. Gerock and was tried on the 7th of December 1818, it involved an otherwise unexceptional Country Dance called Captain Wyke (see Figure 1).  Figure 1. Captain Wyke, from White's Collection of New and Favorite Dances, volume 4; 1816

Figure 1. Captain Wyke, from White's Collection of New and Favorite Dances, volume 4; 1816Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.54.(13.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Several different newspapers reported on this case, in varying levels of detail:

Note: this paper is part of a series on Country Dancing. The full collection consists of:

The Country Dance Publishing IndustryBefore we investigate the legal action, it's worth reviewing a little about the Country Dance publishing industry during the 18th Century and Regency eras. There are various names associated with Country Dancing that might be familiar to modern folk dancers: Playford, Walsh, Thompson, Preston, Rutherford, Astor, Skillern, Straight, Goulding, Longman, Button, Bland, Dale, Cahusac, Falkner, Power, Fentum, Clementi, Hodsoll, Whitaker, Dalmaine... and so forth. They're all known for publishing Country Dances, often in annual collections of 24 dances (an example of which can be seen in Figure 10). But these people were not Dancing Masters, and in most cases there's no evidence that they ever even danced; they're the proprietors of music shops. The publishing of Country Dances was a very small part of their businesses, they primarily sold and maintained musical instruments. Many music shops would also commission, purchase, print and sell their own music. Some also provided bands for hire.  Figure 2. Private Tuition, 1800.

Figure 2. Private Tuition, 1800. © Trustees of the British Museum. If you're interested in knowing more about businesses of this kind, the best material I know of is in a book called The Music Trade in Georgian England edited by Michael Kassler, 2011. It provides a detailed investigation of the business of Longman and Broderip and their successors. It rarely mentions social dancing however, as dances were such a small part of their business. This book also discusses the development of legal copyright as applied to the music industry in Britain.A further characteristic that these publishers have in common is that they're all based in London. There were music shops elsewhere in the country, but London was the centre of the British publishing industry (with Edinburgh a significant second). This legal case involved the publisher John White who was based in Bath. White had two sons, John Charles White and George White. They were outside the London clique, and the first publishers, as far as I know, to actively use the Copyright laws to protect their Country Dances.

The dancing master Thomas Wilson had a poor opinion of most collections of Country Dances, as will become relevant shortly. He wrote of the Country Dance publishing industry in his dissertation on

The dancing master John Cherry, author of the c.1813 A Treatise on the Art of Dancing also wrote of typical Country Dance compositions: It's difficult to say exactly how many country dance collections were published and sold, or who bought them. They were generally (at least in the Regency era) published at a shilling for 24 dances in an annual octavo publication - a format that had been used throughout the 18th Century but was starting to become obsolete. Some vendors sold premium collections of Country Dances in numbered manuscript form, often featuring a bass accompaniment. A few social dancing publications included a printed list of their subscribers, but unfortunately such lists are absent from the typical Country Dance collections. In some rare examples we can identify individuals who purchased and owned such collections, such as John Williams a shoemaker from Manchester; Williams owned at least two Country Dance collections published in 1803 (or late 1802), he might be representative of the type of person who typically bought them. Figure 2 shows what appears to be a collection of Country Dancing tunes being used in a dancing lesson in 1800, the specific tune is called What A Beau My Granny Was. The pupil is shown suffering from poorly fitting shoes, something John Williams no doubt could have helped with! It's likely that many customers treated these Country Dance collections as tune books, and used them for learning a musical instrument. They weren't solely used for dancing.

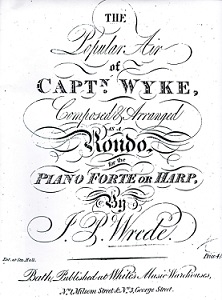

A Country Dance set to Music Figure 3. Captain Wyke arranged as a Rondo by J.P. Wrede, published by White's of Bath, 1817.

Figure 3. Captain Wyke arranged as a Rondo by J.P. Wrede, published by White's of Bath, 1817. Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.125.(41.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED I find the phraseThis was an action by a musician of the city of Bath, against the defendant, a music-seller in Bishopgate-street, for pirating a country dance set to music, called "Captain Wyke," in honour of a Master of Ceremonies of that name, at the Bath Rooms, and composed by the plaintiff.- Morning Chronicle a country dance set to musicquite interesting, it implies that a Country Dancecould exist without music. It's a throw away phrase, so not to be taken too seriously, but it pertains to an issue of interest to modern dance historians.

The curiosity is that most Country Dances published in the greater Regency era include a combination of both a tune and dancing figures. We might naively assume that they're intended to be used together; as indeed they may well have been. But we also know that a different convention existed in the Assembly Halls; the figures could be selected by the lead couple in a Longways Set, without reference to what may have been published. This doesn't imply that the published figures are irrelevant, just that different types of consumer are liable to use published dances in different ways. Indeed, the concept of a The dancing master Edward Payne wrote about the convention for selecting dancing figures in his 1814 A New Companion to the Ball Room. He commented that once a set of figures have been printed alongside a country dancing tune, the dancing public often opted to use them together. He considered this to be a problem, he wrote his book to promote an alternative system in which any figures can be selected for use with any tune. A single country dancing tune may be known by many different names, appear in many different publications, be published with many different sets of dancing figures, over an extended period of time, around the world. A popular tune was often treated as though it were in the Public Domain and was readily republished (publishers might not like their tunes being copied, but they would benefit from copying those of other publishers). This principle of common ownership is particularly relevant to White v. Gerock as, for almost the first time, copyright legislation was being invoked to challenge this convention as applied to social dance music. As we saw in previous papers, the same problems of ownership and copyright were also experienced by the contemporary Quadrille publishers. Both Edward Payne and James Paine complained about unauthorised copying in 1817, they took to signing their official publications by hand to prove their authenticity.

This trial, at least in so far as it has been recorded, didn't directly address what exactly a

Captain Wyke, Master of Ceremonies at Bath Figure 4. A Master of Ceremonies Introducing a Partner, 1795.

Figure 4. A Master of Ceremonies Introducing a Partner, 1795. © Trustees of the British Museum. But the defendant, who is a music-seller in Bishopsgate-street, London, had thought fit to select the particular air called Captain Wyke, so named after the new Master of Ceremonies at Bath- The New Times the composition in question ... meeting with the sanction of Captain Wyke, the Master of Ceremonies, it received his name, and became a great favourite for two seasons with the fair sex who frequented the rooms.- Morning Chronicle It was quite the ruling favourite with all the company at the Bath rooms, and was danced all night, for successive nights together- The New Times Captain George Wyke was voted in as the Master of Ceremonies (or MC) for Bath's Upper Rooms in November 1816. The Upper Assembly Rooms at Bath was one of the most important meeting places and dancing venues outside of London. The MC was an important role, he acted as the figure-head for an Assembly, a promoter and compère; he was also an agent for introductions, a diplomat and regulator. The concept had evolved throughout the 18th Century, and by the time of Captain Wyke there were elaborate rules and expectations for an MC.

As an example of the MCs significance, consider Wyke's predecessor at the Upper Rooms, a man named James King. King was sufficiently famous to appear as a character in Northanger Abbey (Jane Austen, 1803), In addition to the social role, an MC might be required to organise the dancing at an Assembly. Thomas Wilson provided some instructions in his 1816 Companion to the Ball Room, including:

We're told that Captain Wyke accepted the dedication of this tune, and might suspect that he was influential in promoting it. The dancers of the Bath Assembly Rooms probably patronised the tune in honour of the MC himself. It was a danceable tune, and dedicated to a local celebrity; it may (as reported) have been a favourite at Bath for two seasons... until Captain Wyke resigned his position in early 1818.

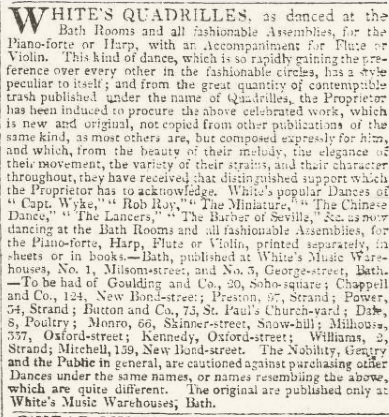

White, the Plaintiff Figure 5. White's Quadrilles Advert, Morning Chronicle, 14th April 1819

Figure 5. White's Quadrilles Advert, Morning Chronicle, 14th April 1819 Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk) The plaintiff was represented to be a young man of great musical genius, whose father kept a music shop at Bath, and played at the rooms and concerts in that city.- Morning Chronicle The plaintiff's father, a performer at the Pump-room at Bath, and a music-seller there, stated that, without partiality, he considered his son a wonderful musician; the air in question was very popular, always played. The sale had diminished wonderfully when the piracy appeared.- Champion and Review The composition became so much a favourite in that fashionable region, and so universally captivated the circles of taste and vivacity there, that it had a rapid run of demand, and from three to four thousand copies were sold in manuscript by the author before it was printed.- The New Times The profits of a successful dance are immense: 3000 copies of this dance were sold in manuscript at Bath for 1s a piece.- Champion and Review Mr. W. giving evidence, said his son's work had acquired great applause, setting aside partiality, it had been danced every night at Bath for a whole season.- Bath Chronicle & Weekly Gazette John White and his sons ran a music shop in Bath. We can estimate from the 1841 census records that John Charles was 23 in 1818 at the time of the case, and George was 18. It's not certain which of the brothers was the plaintiff in this case, but I suspect it was John Charles, for reasons that will become clear shortly. The White business was unremarkable, until around 1814. It was in this year that they began publishing collections of Country Dances with music by John Charles White. Over the following few years they regularly published both music and dances. Their First Set of Quadrilles were registered for copyright in 1817, their 30th Set of Coronation Quadrilles were published in 1821.

White published an advert in 1815 (Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 20th April) in which the business is referred to as White's success as a publisher of social dances increased throughout the Regency period. If we're to believe their testimony, between 3000 and 4000 manuscript copies of Captain Wyke were sold prior to its first printed publication. These manuscript copies were presumably made by hand, so there would be a cost in employing someone to create copies. An income of around 3500 shillings is quite considerable, most country dance tunes couldn't hope for this level of success. John White was a band leader at the Grand Pump-Room in Bath, this role presumably enabled him to promote his own publications, increasing demand for manuscript copies. The anonymous A Gentleman who wrote the Etiquette of the Ball Room (published in Edinburgh in 1823) wrote glowingly of White: Mr White, of Milsom Street, Bath, regularly publishes new Quadrilles in figures and Music; and the principal Music Shops have always in their windows, during the season, tokens of the Quadrilles, as danced at the Rooms, to be had there. Mr White is certainly entitled to great merit for his variety of figures, but to much more, for his music; a great part of which is reckoned superior to any other compositions of the kind; and I am so far justified in this assertion, by White's sets (elegantly bound) being always deemed an useful ornament to the piano.

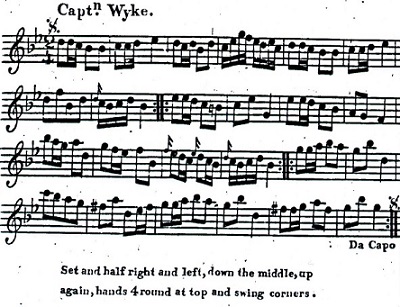

The Composition Process Figure 6. A Musical Genius, 1827. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Figure 6. A Musical Genius, 1827. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

A full band of testimony appeared for the plaintiff, of which the leaders were his brother and his father, the leader of the rooms band at Bath, to prove the extraordinary musical genius of the plaintiff as a composer, that he had composed the first part of this dance in 1814, in the course of five minutes, and the second part in the like space of time, 1816- The New Times His son composed the dance in about 5 minutes, and had composed more than 500 such.- Champion and Review Amongst other efforts of his genius was the composition in question, which was said to have been composed in about five minutes- Morning Chronicle He [White Senior] would not stop at saying he [White Junior] was the quickest composer in England. He had already given 500 pieces of music to the world; and he believed, no man at any age, however advanced, could produce a thousand.- Bath Chronicle & Weekly Gazette The author had first published the dance under a fictitious foreign name, thinking that might be more popular than his own.- Champion and Review The plaintiff's father stated, that his son had composed in his time upwards of 500 country dances, and (allowing for parental partiality) was a prodigy of musical talent. It appeared that the plaintiff had (from modesty), at first, not announced himself as the author of the piece, and had sent it into the world as a production of a gentleman named Reeve, and had entered it at Stationers' Hall in that name, but claimed it to be his property.- Morning Chronicle It was afterwards printed in a collection of the author's, which was sold for 3s6d, and it was afterwards sold as a Rondo.- Champion and Review

Three newspapers emphasise that the tune was composed in around 5 minutes, we're told that this indicates the genius of the young composer. It's unclear whether this claim was intended to be taken literally. It's certainly possible; the German publisher N. Simrock even published tables for constructing English Country Dancing tunes by throwing dice, they were published in the 1790s and were credited to Mozart (not that White would have used this process)! Augustus Voigt (or Voight) published two editions of a similar The copyright laws at this time required works to be registered at Stationers' Hall in order to receive legal protection. Very few musical publications were in fact registered (though many falsely claimed registration on their covers). Even fewer dancing publications were registered. The Whites were unusual, they began registering the publications associated with John Charles from 1814, under his name. From 1816 some registrations begin to appear for Rondos by a J.P. Wrede (not 'Reeve' as reported by the Chronicle), including a new arrangement for Captain Wyke (see Figure 3). It's actually registered twice, first on the 3rd March 1817, and then again on the 25th March 1817. Given that John Charles routinely registered copyrights under his own name, we might infer that Wrede was the pseudonym of George White - but a report of the sister case of White v. Wheatstone indicates that the plaintiff was 23 years old (which identifies him as John Charles), and had a brother called George. Quite why he used a pseudonym after previously registering copyrights using his own name isn't clear.

That 500 Country Dancing tunes had been created by the plaintiff by the end of 1818, and that they may take as little as 5 minutes to produce, indicates the relative disposability of the average such tune. Thomas Wilson tells us in his Companion to the Ball Room that many such tunes were so obscure that professional musicians would not have heard of them. The dancers who requested such tunes often had no idea what they were asking for. This particular title has an interesting history. A tune was first made available through manuscript copies in 1816; it was subsequently included in an 1816 collection of Country Dances printed and sold by White (see Figure 1), this collection was the first formal publication and was registered for copyright purposes in 1816. A Rondo of the same name was then arranged and published separately (see Figure 3), it was registered for copyright protection at Stationers' Hall in 1817. I've reviewed a copy of the Captain Wyke Rondo from the British Library. The publication consists of 7 pages of sheet music and there's nothing in common with the Country Dance other than the name. The Rondo is mentioned in the reports of the trial, but it appears to be an entirely separate work.

Gerock, The Defendant Figure 7. Gerock's Captain Wyke from his Annual Country Dance collection for 1818

Figure 7. Gerock's Captain Wyke from his Annual Country Dance collection for 1818 Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, a.245 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED But the defendant, who is a music-seller in Bishopsgate-street, London, had thought fit to select the particular air called Captain Wyke, ... and piratically published it in London for his own account, at 1s. each copy, whereby the sale of the plaintiff's book, of which that air was the principal attraction, was wholly lost, and this action was brought to recover compensation for the injury sustained by the plaintiff.- The New Times ... the defendant published the alleged piracy in question, of which he printed 125 copies. According to the evidence, it did not appear that he had sold more than two or three copies of it, and had now 116 copies on hand- Morning Chronicle George Peachy, the defendant's shopman, proved that his master had, to his belief, sold no more than two copies of the piracy. There were now 116 copies in his master's possession, but he had not brought them with him.- Morning Chronicle Mr. Frazer proved that he bought the Dance at the Defendant's shop.- Morning Post William Walton stated, that he was employed by Mr Gerock to print the publication in question, he had printed six copies of the rondo, and had been ordered to print 50; but Mr. Gerock finding there was a piece of work about the dance, recalled the order and the plates were sent back.- Champion and Review James Power received a manuscript from the Plaintiff in the early part of 1817, and delivered it to Mr. Bates, to have it engraved. Mr Munroe received a manuscript copy of the set of dances in 1817, from the Plaintiff, to have it engraved. He delivered it to Mr. Bates. Mr. Bates proved having received two copies, and engraved them. The first was the copy of a rondo, the second a set of dances. This was in April 1817. In October last witness received a set from the Defendant in manuscript, and an order to engrave it, which he did.- British Press The Defendant's Shopman proved that his Master stopped the sale, so soon as he was informed of the Plaintiff's claim.- Morning Post Christopher Gerock ran a music shop in London, he's best remembered today as a vendor of Flutes and Barrel Organs. He'd moved to London from Germany around 1795. It seems that he employed an external engraver and printer. He'd only commissioned a small print run of 125 copies, almost none of which were sold, and he'd cancelled a printing of the rondo when legal proceedings began. Several of Gerock's Country Dance collections are still extant, he published annual collections of 24 Country Dances from at least 1812. He was aware of the existence of copyright legislation as his annual collection for 1817 made repeated references to it (unlike his earlier publications). These references didn't reappear in his annual collection for 1818, though curiously, that collection does include a Country Dance called Captain Wyke (see Figure 7). If Gerock's Captain Wyke in Figure 7 is compared to White's version in Figure 1 it can be seen that the two dances, both tunes and dancing figures, have almost nothing in common other than the title. Gerock's version is also entirely different to White's Rondo from Figure 3. I presume that Gerock printed another (now lost) Captain Wyke that more directly duplicated the Whites' dance. Either that, or the title alone was sufficient to invoke Copyright legislation. It seems that Gerock was accused of copying both the Country Dance and the Rondo, and the surviving Gerockean Captain Wyke is unrelated to either. As an aside, it's worth noting that the name Captain Wyke was attached to some other dances that weren't involved in this trial. For example, Astor & Horwood published a tune called Captain Wyke in their 1818 annual collection of 24 Country Dances. Clementi & Co. published a verbatim copy of Captain Wyke in their c.1817 No 12 of Martin Platts' Periodical Collection of Popular Dances. The Preston & Son collection for 1818 published a copy of White's tune, under the name Captain Dyke; it's unclear whether that was a typographical mistake, or a cyncial attempt to avoid prosecution.

Payne, the Middleman Figure 8. Political Whisper, 1779

Figure 8. Political Whisper, 1779 © Trustees of the British Museum. It was also proved ... that the defendant had not printed from the plaintiff's copy, but from a manuscript given him by a musical person, who had scored down the tune from hearing it played at Bath.- The New Times Mr Payne, a musician, proved that about two years since he sold a manuscript copy of "Captain Wyke" to the defendant, which he had composed from having heard it played by other musicians. He never heard that the plaintiff was the author of it. This sale took place before the plaintiff's work appeared in print.- Morning Chronicle Benjamin Payne, a musician, was in the habit of supplying the Defendant with country dances; he furnished him with Captain White (sic) about two years ago; he learnt it by hearing it played; he did not know Mr. White was the author of it; he never heard of Mr. White.- British Press The shopman of the Defendant proved, that his master published the dance in question in October last; he published it from a manuscript copy which he purchased of the last witness. It had been published by other persons in London the year before.- British Press It's here that things start to turn complicated. Gerock didn't outright copy a printed publication, but had the tune from a third party. The musician in question was a Benjamin Payne. Payne himself wasn't accused of having done anything wrong, but it seems his ear for music may have been a bit too perfect... if he'd misremembered the tune then the new work might not have been considered a copy. Perhaps if they'd changed the title of the dance the copyright problems could have been avoided.

The sister case of White v. Wheatstone also involved a third party who passed music along from Bath to a London based publisher, hinting that this might have been a common practice at the time. The report of the sister case in the Morning Chronicle, 9th December 1818, mentions

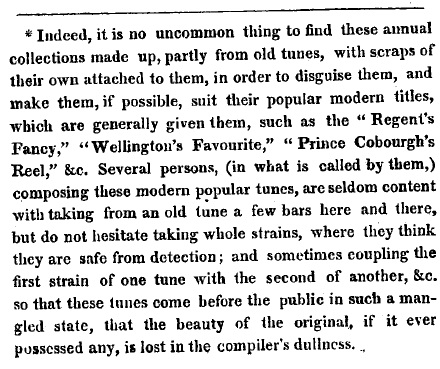

Wilson, and the Case for the Defence Figure 9. A footnote from Thomas Wilson's 1816 Companion to the Ball Room.

Figure 9. A footnote from Thomas Wilson's 1816 Companion to the Ball Room.

[the defence] had undertaken to prove, namely, that this air was not an original composition, but itself a piracy.- The New Times Mr. Wilson was then called, who stated, that the dance was not original, but a selection of passages from old tunes. The whole might have been cut out with a pair of scissors and put together. He did not think there could be an original country-dance: he considered three notes in succession as constituting a passage.- Champion and Review Mr Wilson, a professor of music, gave it as his opinion, that this piece was not original, inasmuch as it was composed of bars of a great many other country dances ... He admitted, however, that so far as the combination of these scraps went the piece was original. But otherwise he would not admit its originality.- Morning Chronicle A Mr. Wilson and a Mr. Richards, two musicians and composers, deposed that the air of Captain Wyke was not original, but throughout a compilation of bars and passages from other compositions of a similar kind, long known ... and that immediately on hearing the piece in question they could recollect many passages long familiar to their ears from other compositions.- The New Times Mr. Campbell then called Mr. Wilson, a Musical Professor. He had seen the dance of Captain White (sic): there was nothing original in it. It was made up of two or three bars of "Off She Goes." There were also notes from "Love in her Eyes," the "Irish Washwoman," and other old tunes.- Morning Post Mr. Wilson stated that it set off with "Love in thine Eyes". The fifth bar was the same. A number of bars were taken from "Braham's Concertante," not in imitation, but the same passages. There were bars from "Off she goes," two half bars put together from "The Irish Washerwoman," some from "Morgan Rattler." The whole might have been cut out with a pair of scissors and put together.- The News Mr. Richards, leader of the band at the Royalty Theatre, said, the air was not original; he could show well-known pieces from which several bars were taken. He thought there was no originality in dances.- Champion and Review

The defence made a strong and important counter-argument. They employed expert testimony to argue that White's Captain Wyke tune was not in fact original, but was made up of fragments from many other tunes. One of these experts was a Mr. Wilson, probably the dance master Thomas Wilson. There is room for doubt in this identification as The British Press identified him as a

Thomas Wilson wrote in his 1816 Companion to the Ball Room about how Country Dancing tunes were often made up of fragments from other tunes. He wasn't writing specifically about Captain Wyke, but more generally: Another expert, Mr. Richards supported Mr. Wilson, and argued that no Country Dance tune could ever be considered copyrightable, as they're all derivative.

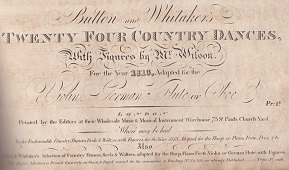

Whitaker, and the Case for the Prosecution Figure 10. Button & Whitaker's 24 Country Dances for the Year 1813, with Figures by Mr. Wilson.

Figure 10. Button & Whitaker's 24 Country Dances for the Year 1813, with Figures by Mr. Wilson.

Mr. Whittaker, a professor of music, was then called for the plaintiff, and he swore distinctly that the plaintiff's work was a perfect original, in its combination of parts of old tunes.- Morning Chronicle Mr Whitaker stated, that Mr. Gerock's publication was a complete piracy without doubt.- Champion and Review Mr Whitaker, the composer, was called, who proved that the publication of the Defendant was precisely the same as that of the Plaintiff. It was a complete piracy. Cross examind - there was one note more in the fourth bar, but the fifth bar was the same. In the fourth bar of the second strain there was a colourable alteration, a 'd' instead of a 'b', but in substance it was the same.- British Press Mr Whitaker being called again, stated, that the circumstances of the possibility of finding the same bar in different pieces of music did not at all affect their originality. He did not think that a single bar formed a musical sentence. The first bar of "Love in thine Eyes," might be found in 5,000 pieces. There was scarcely a single bar in any eminent composer's works, that is, separately.- Champion and Review One of the witnesses admitted, on cross-examination, that even the great Masters in their first rule of compositions, took in bars and passages from the performance of other composers; that Mozart himself was a close copyist of Haydn; and that it was highly natural for a composer, who was but a combiner of sounds, to adopt passages dwelling on his recollection from the performances of others, without adverting to their printed works.- The New Times The main independent witness for the prosecution was Mr. Whitaker, presumably John Whitaker of Button & Whitaker. If this identification is correct, he regularly worked with Thomas Wilson, and published many of Wilson's books (see, for example, Figure 10). His testimony challenged that of Mr Wilson, he argued that it's impossible to create music without reusing bars from other works.

John Whitaker's business partner, Samuel Button, had issued a strong statement in support of copyright for Country Dances in 1807. The statement was related to a tune called The Fairy Dance (The Star, 3rd July 1807):

As we've seen, Thomas Wilson had a poor opinion of most Country Dance collections. He justified his own involvement with the Country Dances of Button & Whitaker in the following passage from the Companion to the Ball Room:

Legal Arguments, and Summing Up Figure 11. A Counciller, 1801. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Figure 11. A Counciller, 1801. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Mr. Campbell [for the defendant] then proceeded to address the Jury....With respect to the compositions now under consideration, he could he thought prove that they differed most material. The Plaintiff's 'Captain White,' (sic) differed from the Defendant's in figure, and he was informed that gentlemen were in attendance with their instruments, and would with his Lordship's permission, play over the compositions, when their variance would be most apparent....The fact was, that [Captain Wyke] had gone out of fashion; it had ran, according to the Plaintiff's account, twelve months, and the good people of Bath now wanted something new. On this ground he trusted, even if he should not be so fortunate to get a verdict for his client, the question of damage would become merely nominal, and would be limited to the lowest coin in existence.- British Press Mr Campbell, for the defendant, submitted three objections to the plaintiff's right to recover: 1st, He had not proved the declaration, which called this sheet of music a "book", whereas the alleged piracy was only the piracy of a single leaf of the "book" published by the plaintiff, which consisted of a set of country dances. 2nd, That this action could not have reference to the manuscript publication of this piece, of which there had been 3 or 4000 copies sold in that form, because the Copy-right Act did not contemplate any thing but printed works; and 3rd, That the plaintiff could not set himself as the author, having distinctly announced the piece as the production of a person named Reeve, and recorded it as such at Stationers' Hall, by which record he was concluded.- Morning Chronicle Mr Scarlett, in his address to the Jury ... [said] ... He was not ashamed to know as much of music as became a gentleman. But he was confident that no man whose taste was not confined to a "bagpipe", or whose experience never went beyond a "reel", not to know that it was scarcely possible for a musical composer in the range of his compositions, not to include from the recollections dwelling on his mind, some bars or passages he might have heard before, without any design of plagiary upon the works of others. He contended, however, that the composition of the plaintiff in this case was not a plagiarism, but a combination requiring that share of talent and genius which it was the object of the Legislature to protect.- The New Times The report in The New Times contained some additional witty reposts between the opposing lawyers that I've not included. The points raised here are actually quite interesting, as they question the interpretation of the 1710 Statute of Anne copyright legislation. Some of the issues raised required further consideration by The Court of the King's Bench, so the Jury were only required to decide whether this specific country dance demonstrated sufficient skill and originality to qualify for legal protection. Some of the issues had already been investigated in previous trials. For example, Bach v. Longman in 1777 concluded that music was subject to Copyright; Hime v. Dale in 1803 determined that a single sheet of song lyrics could be protected; and Clementi v. Goulding in 1809 made a similar decision for a single sheet of music. At least three other complaints involving Country Dances had been registered in 1815, each involving the London based publisher James Platts; the complaints, together with the official responses, are available from the National Records archives. It's not clear how those trials ended, they may have been dismissed. The injunction of Platts v. Button & Whitaker is readily referenced, it appears to have been dismissed; we've investigated it further here. Other trials had investigated the link between copyright law and common law, between English and Scottish legal systems, of foreign publication and publication by foreigners, royal privilege, and the extent to which intellectual property can be owned. Justice John Bayley decided that the concerns regarding the scope of the existing copyright legislation should be decided elsewhere, even though the existing case law was almost conclusive; the jury was allowed to make a decision, but it would be subject to a legal review.

The Verdict Figure 12. Criminal Court, 1796. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Figure 12. Criminal Court, 1796. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

The Jury found for the plaintiff, in consideration of the 125 copies said to be printed by the defendant - Damages 5l.- The New Times It was stated, that the plaintiff sought not for damages, but the security and protection of copyright to his works. After a trial of considerable length, to which much ingenuity and some wit were displayed by the Counsel on either side, the Jury returned for the plaintiff, damages £5. This verdict by the statute subjects the defendant to "Double costs of suit"- Bath Chronicle & Weekly Gazette The jury decided that this Country Dance was worthy of legal protection, and the defendent was charged £5 plus double costs. This hardly seems much of a fine given the quantities of money the plaintiff alleged had been lost... perhaps the Judge had accepted that there were other explanations for why the Country Dance was no longer selling in Bath. One reason might be that the local market was already saturated, but perhaps a more probable explanation can be found in Captain Wyke himself having resigned as the Master of Ceremonies in Bath. The new MC at Bath, James Heaviside, was elected in February 1818. It's likely that local support for the dance would have decreased significantly at that time, and the piracy of the tune in London was entirely coincidental. Aside: just for scale (and because I think it's amusing), a dance master called Robert Le Mercier was fined £1000 in 1814 forholding criminal conversation with the wife of Mr. Plowes, a respectable London merchant. Gerock's £5 fine seems tiny in comparrison. In the words of the Leeds Mercury (20th August 1814)Le Mercier rightly punish'd is, By Britain's equal law; He should teach Ladies proper steps, And not a grand faux pas. In addition to the finding itself, an observation that modern Dance Historians might find interesting is that Thomas Wilson (on whom we rely for much of our knowledge of Regency era dancing) wasn't always right! He, if his identification as the defence witness is correct, asserted that the tune was not original, and that it couldn't be protected in law; this personal opinion was not upheld by the Court.

The King's Bench ReviewThe remaining legal questions were reviewed on the 25th January in the following month, and the results were reported in The New Times on the 26th January 1819. There were two issues up for review; first, whether a page of a Country Dance collection qualified as a book for copyright purposes; second, whether the manuscript documents were subject to copyright protection, whether they voided the copyright of the subsequent publication, and at what date the 28 years of copyright protection began.The New Times reported: The verdict stood.The Court was of opinion, on the first point, that the term book was in law quite appropriate to the musical composition in question; and upon the second, that whether the plaintiff in this case published in manuscript or in print, he was fully entitled to protection under the Statute of Anne, and therefore the Rule was refused.

A more complete description of the review can be found in the 1820 Reports of Cases Principally on Practice and Pleading, determined in The Court of King's Bench. It includes Lord Chief Justice Abbott's conclusions: Curiously, the review seems not to have directly addressed the question of when the Copyright protection began, and therefore at what date it would expire. It's implied to start with the sale of the manuscript copies, even though the copyright wasn't registered with Stationers' Hall until the dance became available in print. It's possible that the subtleties of that issue were lost in transmission between the two courts.

White v. Wheatstone, 1818On the 9th December 1818 the Morning Chronicle reported on an almost identical case, this time involving dance tunes called Lady Caroline Morrison and Rob Roy. The defendant was different, but it involved the same plaintiff; many of the lawyers, witnesses and evidence were also shared; and the result was the same for the same reasons. Wheatstone was also fined 5 pounds and double costs (the costs were 40 shillings).Interesting details include that: the tunes were originally sold in manuscript form at 1s a piece - 4000 copies of one were sold, and 800 of the other; they were then sold in a printed collection; Misters Piele, Jansen, Wilson, Dale and Bolton all argued that the Country Dances were not original and not subject to copyright; the jury, with prompting from the judge, decided otherwise. This, and other similar disputes, are discussed in another of our papers.

Just for the record, some sources refer to this case as White v. Geroch, and some refer to the tune as either Captain White or Captain Wake. These are errors, but they are early errors. If you'd like to know more about social dancing in Bath during the Regency era, I can recommend Ian Perkins' As Danced at Bath blog. And finally, if you'd like to dance Captain Wyke using the figures published by John Charles White, we've animated an interpretation of it here. As with all such research, new information can become available at any time; if you can shed light on any further aspects of this case, we'd love to hear about it, so please do get in touch.

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved