|

Paper 19

Regency Era Country Dances - Form

Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor

[Published - 18th January 2016, Last Changed - 21st June 2025]

Country Dances are a social dance form that have been enjoyed by dancers around the world for many generations, the rules for dancing them are consequently very well understood. In this paper we'll question that understanding, and consider how they were taught by the Dancing Masters of Regency era London. This research paper is complemented by our previous papers on Regency era Country Dancing Figures, Country Dancing Music and the Country Dancing Industry.

These papers generally start with a reminder that the evidence we have from 200 years ago is fragmentary, and open to skewed interpretation. I'm therefore reluctant to place too much significance on the information we have - the Regency was a period of roughly 10 years, the population of London alone has been estimated at 1.4 million people in 1815 - there's a vast scope for variation in dance styles beyond what we have explicit evidence for. The works of the Dancing Masters are a biased source of information (they wanted to sell tuition to patrons who could afford it), but they're the best information we have. If you wish to reproduce historical dances in a form other than how they're described in this paper, that's okay; it's likely that someone 200 years ago preferred your way of enjoying them. But if you're keen to remain as authentic as possible, this paper explores what's known.

In this paper the references to John Cherry refer to his c.1813 A Treatise on the Art of Dancing in the Ball Room, and a reference to Thomas Wilson refers to the 1820 edition of his The Complete System of English Country Dancing, unless otherwise noted.

Note: this paper is part of a series on Country Dancing. The full collection consists of:

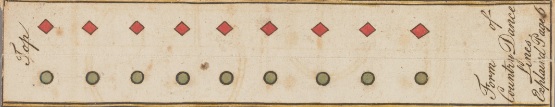

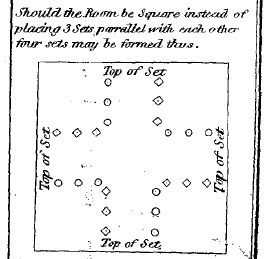

Figure 1. The form of a Country Dance, A Treatise on the Art of Dancing in the Ball Room, John Cherry, c.1813

Longways for as many as will

Country Dances have appeared in print ever since John Playford printed his first edition of The English Dancing Master in 1651. Many of those early Country Dances, and most in the later editions of that same work, feature the term Longways for as many as will , a term that describes the typical Country Dance form that survived into the Regency era. Couples form up in a long line, facing their partners (see Figure 1), and perform a sequence of dancing figures in time to the music, the result of which leaves the couples in a new position within the line, and ready to repeat the dancing figures from their new position. There's no proscribed limit to the number of couples, hence they're for as many as will .

Several Regency era dancing masters published works describing the basic form of the Country Dance. They often emphasised the Scientific and Mathematical nature of the dance. For example, John Cherry writing c.1813 wrote that (page 1) Country dancing is the grand feature of the English ball room amusement, and though frequently executed with elegance and much apparent ease, is nevertheless of very scientific composition, and is founded upon strict mathematical principles . Thomas Wilson writing in 1820 wrote A Country Dance, as it is named, is almost universally known as the national Dance of the English, and as correctly known, is constructed on mathematical and other scientific principles . Both writers went on to define the rules inherent in Country Dancing; rules that Wilson believed to have been perfected within his own life time, and making the Regency era Country Dance superior to earlier incarnations of the same dance form.

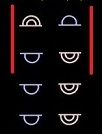

A Country Dance is performed in couples. Couples should ideally be made up of a man and a woman, the male partners in one long line and the ladies in another facing them, but Cherry informs us that (page 5) it sometimes happens, from their being an unequal number of ladies or gentlemen, that ladies are placed on the gentlemen's side, and gentlemen on the ladies side; but this is inelegant, and should be studiously avoided. . Figure 1 shows the form of a Country Dance, as depicted in Cherry's c.1813 A Treatise on the Art of Dancing in the Ball Room, the circles represent the gentlemen and the diamonds represent their partners. He went on to report (page 8) that The distance of the ladies' line, or side of the dance, from that of the gentlemen, is about four feet and a half, and the distance that one couple should stand from another, is two feet and a half. . The lines must remain perfectly straight otherwise, the figure that is performing, and which ought to be seen as plainly and correctly as if drawn upon paper, would seem nothing more than a rude bustle and an unmeaning confusion . If two men were dancing together, the standard etiquette rules (as recorded in numerous sources) required them to start at the bottom of the Country Dance.

A typical Country Dance formation involves the leading couple dancing with the two couples below them, they're sometimes referred to as the first, second, and third couples; each couple will have a distinct role in each dance. The first couple will typically progress one position down the line during the figures, changing places with the second couple; the next iteration of the dance begins with them progressed one place, and dancing with a new second and third couple (the new second couple will have been the third couple in the previous iteration). This arrangement of a Country Dance is referred to as a Triple Minor.

Duple and Triple Minors

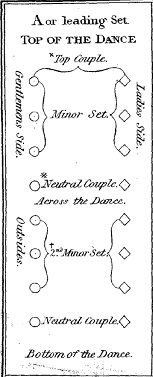

In modern terminology, a duple minor is a country dance involving two couples in each iteration of the figures; a triple minor is a country dance involving three couples. The anonymous A.D. writer of the 1764 Country-Dancing Made Plain and Easy referred to these configurations as Single and Double dances, but that terminology has fallen out of use. A modern caller will typically start a Country Dance by calling hands four or hands six and the dancers will form sub-groups of two or three couples down the length of the lines. Each sub-group (referred to by Thomas Wilson as a Minor Set ) dances the same set of figures. Some sequences of Country Dancing figures are capable of being danced with the active involvement of just two couples, others with three, so it's a useful convention to distinguish between them.

But duple minors aren't something Regency era writers referred to. They expected three couples to form a minor set, even if the figures would only require two. Cherry wrote (page 40) for as three couple can perform any figure which has been composed, three couple are always considered indispensible to form a set for the figures, though, in some dances, two only be made use of . If the third couple had nothing to do, they would wait politely attentive, and would become involved in the following iteration of the dance. Wilson referred to an inactive third couple as a neutral couple .

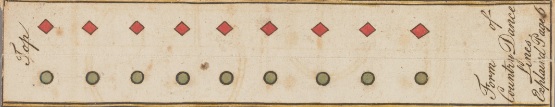

Wilson added an extra layer of complexity. He always encouraged a neutral couple to be present between each minor set; if the figures only required two couples (a duple minor) the neutral couple was the third couple in the minor set (so far this matches what Cherry wrote); but if the figures required three couples (a triple minor) Wilson had a 4th couple allocated as the neutral couple. Figure 2 is an extract from Wilson's Plan of a Country Dance in which the neutral couple between two three-couple minor sets is clearly depicted.

Cherry, however, didn't require a 4th couple to remain neutral in a triple minor. W.H. Woakes in his 1825 Etiquette of the Ball Room recorded It is usual after the leading couple have performed the figures down three couples, for those at the top to begin, and generally it is sufficient, but, if the dance should be composed of more than three figures, to prevent confusion and to give the necessary distinctness to each performance, a wider separation is recommended. (the same quotation can also be found in the anonymously published 1825 Analysis of the London Ball-Room). Woakes first alludes to an important point we've not yet mentioned - that once the lead couple has progressed sufficiently far down the dance, a new lead couple starts dancing at the top of the set and follows the first minor set down the line - but he also hints that Wilson's additional neutral couple would only be injected where the dance particularly needed it. Wilson defended the need for a neutral couple between the minor sets as follows (page 158): A neutral couple ... is constituted ... to prevent confusion in the Dance, too frequently occasioned by the Figures interfering and becoming entangled with each other . Some rare figures existed where the top couple would lead up the set, and the bottom couple would simultaneously lead down - such figures could result in collisions unless a neutral couple was standing between the minor sets and taking up some room. Wilson wrote further on the subject in a footnote in his 1816 A Companion to the Ball Room (4th ed. p243), where he admitted that his convention was unusual.

An important variant of the Country Dance is one which involves more than one progression. That is, the lead couple progresses into second position, and then again into third position, within a single iteration of the dance. Such arrangements are unusual in the published choreographies of the Regency era, but the concept was not unheard of. In modern terminology we might refer to them as double progression triple minors , or even triple progression triple minors . Wilson acknowledged the existence of multiple progressions, he wrote that One Dance may contain but one progressive Figure, or be set with four, and both be equally correct . There are figures that might be interpreted as doubly progressive, such as Lead twice down the middle and up again. If more than one progressive figure is used then neutral couples can be absorbed into a minor set part way through an iteration of the dance; it therefore requires greater attention and skill from the dancers. Choreographies involving multiple progressions are often enjoyed by modern dancers, but are unlikely to have been danced at public assemblies two hundred years ago. Choreographies are occasionally found that might imply a double progression, an example of which can be found in an 1802 dance called Miss Coventry's Strathspey by John Hammond; but other interpretations are usually possible, including an error in the source publication.

Note: duple-minor Country Dance variations did arrive in 1817 in the form of Wilson's Ecossoises dances; we'll explore that further shortly. We'll also explore how the first couple might begin improper (on the wrong side of the set), another innovation of the Regency era not seen in the regular Country Dancing choreographies of the period. Duple Minor dances were danced without neutral couples in the 1760s, the anonymous A.D. writer in 1764 explicitly referred to them. It therefore appears that this practice had gone out of fashion in London by the 1810s, though choreographies that only involved two couples were still being published throughout the Regency period.

Occasionally an exotic choreography can be found that defies the normal conventions. An example of such can be found in a dance called The British Guards in James Fishar's 1778 Twelve New Country Dances, Six New Cotillions and Twelve New Minuets. This dance is arranged for 10 couples, in 32 bars of music, ending with a single progression as usual; the first 16 bars are led by the couple who happens to be at the top of the set in any given iteration, the second 16 by the lead couple as though in a normal country dance. Another anomaly can be found in Charles Metralcourt's 1793 The Sportsman, this country dance was arranged for four couples; the same can be said for John Rutherford's c.1773 Les 4 Frerers. James Platts published his La Mêlange medley country dance in 1791, it involved a triple progression. It's rare for a Country Dance collection to contain a choreography that doesn't follow the standard progression system, but it's not unheard of.

Three-Couple Sets

The three-couple set is a favoured dance for the modern-recreation of historic dance halls, but it wasn't (as far as I can tell) actively taught by the Regency era dancing masters. It's a variation of a longways country dance arranged for just three couples, where the lead couple progresses twice within each iteration of the dance, ending at the bottom of the set; the next iteration begins with a new lead couple. It's a very sensible arrangement which ensures a fair share of dancing to the dancers. But is it historically plausible?

Well yes, it is, though the evidence is thin. Wilson states numerous times in his works that a Country Dance can be performed with a minimum of just six people, and we've already seen that double progression is legitimate in a Regency era Country Dance, albeit unusual. So on that basis it is consistent as a special case variation of the normal rules, but it's a challenge to find any evidence of three couple sets being danced 200 years ago. The best Regency era evidence I know of is shown in Figure 3, another extract from Thomas Wilson's Plan of a Country Dance. It shows a special arrangement of four three-couple sets within a square shaped room. Wilson didn't explain how this arrangement would be used, but progression from one set to another isn't easily arranged without gender swapping, so it presumably required what modern enthusiasts would perceive as a three-couple set. This arrangement could be extended for longer sets than just three couples, but the image happens to depict three couples in each of the sets.

Wilson may not have discussed this format, but he did provide rules for arranging a company into multiple longways sets if there were too many for a single set. He caused several such sets to be arranged in parallel, and required that the same dancing figures be used across them. This involved a negotiation to ensure a consistency of figures across the sets; the same would presumably be true of this exotic arrangement of four three-couple sets.

A few reports of historic Balls do mention a Set of just three or four couples. For example, the 1826 History, Antiquities, and Description of the Town and Parish of Worskop reported on an 18th Century Ball in which the old duchess herself, in the hilarity of the occasion, danced down three or four couples . The anonymous 1828 Lairds of Fife recorded in fiction that the august pair danced down three couples . Some historical Country Dances exist which feature the instruction Play'd 3 times over , presumably implying that only three iterations of the dance were envisaged, two such examples can be found in Thomas Bolton's 1808 New Musical Publication (including the Wybrarian Waltz).

From a practical point of view, logic dictates that the three-couple Set must have been known 200 years ago. It's an obvious variation on the regular Country Dance, and it enables six dancers to enjoy a dance on their own. The anonymous A.D. writer of the 1764 Country-Dancing Made Plain and Easy explicitly arranged a dance named New Twelth Night for three couples (probably as a teaching aid), it involved a double progression. A.D.'s dance might legitimately be described as a three-couple Set. Small gatherings in private parlours might have enjoyed this format even if it wasn't used in the elite Assembly Rooms. By the 1820s the Country Dance was sometimes referred to as a Kitchen Dance; this hints that they were enjoyed by the working classes, perhaps in cramped conditions, where a three-couple Set would be particularly convenient. The dancing masters may not have written much about three-couple Sets but I don't think we can assume they were unknown.

Modern adaptors of Regency era Country Dance choreographies routinely arrange them as three-couple Sets. That's sensible if the goal is for modern dancers to enjoy a historically themed dance in just three iterations of the tune; but it's worth remembering that the original choreography probably implied something else. The Country Dance animations here at RegencyDances.org are usually arranged as longways dances, but please feel free to rearrange them as three-couple Sets for your own enjoyment.

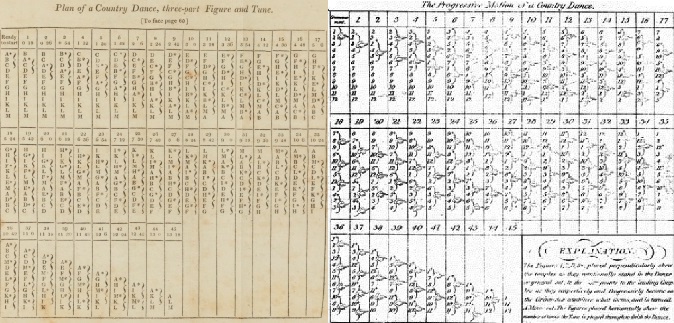

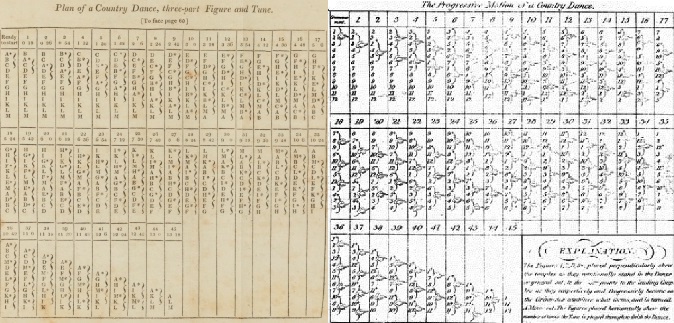

Figure 4. Cherry's c.1813 Plan of a Country Dance, and Wilson's c.1820 The Progressive Motion of a Country Dance

Courteous Starts

I'm not sure how to name this concept, so I've invented the term Courteous Start . It's a concept that didn't need a name 200 years ago, as it was simply the way to start a Country Dance; but it's unusual in modern dance halls. The courteous start involved the participants in a longways set waiting attentively to dance until the lead couple reached them; it's a concept discussed by both Cherry and Wilson. It exists in contrast to the simultaneous-start of multiple minor sets that is used in most modern recreations of historic Country Dances.

Figure 4 shows John Cherry's Plan of a Country Dance, three-part Figure and Tune, it clearly shows the progressions in a Country Dance. It's arranged for 12 couples, and involves 45 iterations of the dance. The first iteration involves the three couples ABC dancing, followed by ACD and ADE ; then a fresh minor set starts and we see BCD, AEF dancing, followed by BEF, AGH ; and so forth. By iteration 12 all of the dancers are moving; the dance ends at iteration 45 when the first couple A reach the end of the longways set for the second time, the second or B couple being left at the top of the set, ready to lead the next Country Dance. The information was sufficiently useful that Wilson included essentially the exact same table in his 1820 Complete System of English Country Dancing (despite its mildly contradicting the progression system that he personally recommended, see also Figure 4). Figure 5 shows an image from Rowlandson's 1817 Miseries of Modern Life series in which the bottom three couples can be seen waiting for their turn to join a Country Dance. This extended period of being stood-out at the start of a dance could be a convenient opportunity to chat with your partner.

The first couple held a position of honour, and the courteous start emphasised that; the waiting couples were supposed to stay quiet and patiently await their turn. The etiquette guides provided detailed instructions for how the lead couple would be selected at an Assembly Room, typically the first lady to arrive was assigned the lead in the first dance, and the second in the second dance, and so forth. In some Assemblies the precedence was allocated by rank; the Morning Post (29th June 1827) carried a humorous and fictional report of a Ball at Bath in which the grand-daughters of a Peer and the daughters of a Baronet were in competition for a privileged position in a Country Dance, they appealed respectively to the Chamberlain and the Herald for a decision: Each of the referees returned an answer, as in gallantry and gratitude bound, in favour of the Lady who had honoured him by her query; but before the formal and necessary steps such a momentous affair required could be gone through with, the Bath Season had elapsed ! Rank based precedence may have been going out of fashion at many Assemblies by the time of the Regency, the Salisbury and Winchester Journal carried an account in 1781 (15th January) protesting how the positions of honour at the top of a Country Dance were regularly being usurped at the Salisbury Assemblies, and suggested that this would lead to a general decay in genteel dancing. Some Assemblies did retain precedence rules however, including the Kingston Assembly until at least as late as 1816, and the Lowe brothers in their Ball Conductor & Assembly Guide promoted precedence rules for Ladies of quality into the 1820s and well beyond.

The time required to dance a Country Dance could vary wildly. In the Figure 4 example, Cherry has each iteration of the dance take 18 seconds, and the full 45 iterations take 13 minutes and 18 seconds (there's a minor error in his calculations, it should take 13 minutes and 30 seconds). A report in The Morning Post (30th April 1803) mentioned a Ball with at least fifty couple in which Sir David Hunter Blair was the only dance for two hours and a half

! A more typical Country Dance might have involved as few as six couples, potentially in multiple columns, and take a relatively modest length of time to dance through. Edward Payne had a rule at his Assemblys that Country Dancing would commence once six couples were ready. Reports from Regency era Balls sometimes mention the number of couples dancing. Examples include: 30 couples (Morning Post, 18th January 1817), 16 couples (Nottingham Gazette, 12th February 1813), 10 couples (Morning Post, 31st March 1807), 30 couples (Saunders's News-Letter, 14th march 1820) and 20 couples (Belfast Commercial Chronicle, 1st March 1809). The reports of a Royal Ball from 1788 reveal that two Country Dances were gone down by the Prince of Wales and his friends in half an hour, there were variously reported as being either 8 or 12 couples in the Set on that occasion (Stamford Mercury, 25th January 1788, and Derby Mercury, 17th January 1788). The Assembly Rooms in Edinburgh in 1787 enforced a rule that Each set to consist of twelve couple, and no more (Caledonian Mercury, 26th March 1787), whereas the Margate Assembly Rooms in 1802 only required a longways Set to split when upwards of twenty couple stand up .

Figure 5. Rowlandson, More Miseries, 1807

Somewhat ironically, the length of time a couple might spend stood-out could, in some assemblies, result in dancers actively avoiding being the first couple to lead down a Country Dance. Wilson and Payne both wrote of this issue in their respective etiquette guides. The convention at the time required the first couple to start at the bottom of the next dance; the concern was that those dancers might spend the rest of the Ball towards the end of the set, with not much to do. Some dancers would rather dance the first Country Dance from second or third position. In some assemblies the Master of Ceremonies would lead down the first dance, thereby avoiding this problem for the other dancers.

The length of time that some dancers might spend in motion (perhaps in the longer of longways sets) could result in a different problem; dancers could become fatigued, and leave a Set early, contrary to the prevailing etiquette rules. The following passage from an 1812 novel called Temper, or Domestic Scenes by Amelia Alderson Opie involves a discussion between a couple in a Country Dance:

Having danced down with only half the couples standing up who had begun, Popkinson told Emma he supposed she would rest herself, and not join the second dance till it was near her turn to begin.

No, sir, replied Emma, let us do as we would be done by. If all dancers did as you recommend me to do, those who are at the bottom of a set would be served as you and I were just now, and would have scarcely couples enough to form a dance.

The character of Emma in Opie's novel is a naive young dancer familiar with the conventions of private Balls, but attending her first public Ball at Kendal (a town in the North of England). She struggled with the discovery that the etiquette rules she'd been taught were routinely ignored at some public gatherings, she was unsettled by the pushing and shoving as dancers competed for a position at the top of the set, and by some dancers abandoning the Set once they'd finished dancing down. It's clear that in some gatherings the etiquette conventions promoted by Wilson et. al. (and enforced at many Assembly Rooms) were stretched, abused and outright ignored.

Many assemblies acknowledged the effort required in dancing Country Dances, and only permitted two of them to be danced in succession, with an explicit rest period between each pair. Edward Payne, writing in 1814, advocated that brief periods of Waltzing be introduced during the resting period. This was also a convenient time to change partners before the next pair of Country Dances.

Calling A Dance

The primary distinction conferred upon the top couple was the right to select the tune and figures that were to be danced by the company. This was referred to as Calling a dance.

It's unclear when the concept of turn based calling was introduced, but it was explained in 1752 in The Manchester Mercury (28th November 1752) as being an innovation from the Twelve Penny Hops attended by Journeymen, Haberdashers, Clerks, Apprentices, Milliners and the like. Their writer described an assembly he'd visited in Manchester: I found the wenches warm in the Pursuit of their Pleasure, and every one panted with Impatience till it should be her Turn to call, which it seems is a Phrase for leading down the Dance, or being for a while the Queen of the Party . The implication is that the concept of taking it in turns to call was new, and needed explaining. If this is correct, the convention from the worker's Hops had infiltrated many of the elite Assembly Rooms by the start of the Regency. As late as 1787 the Assembly Rooms in Edinburgh retained their rules of rank based precedence (Caledonian Mercury, 26th March 1787), but by 1804 the Assembly Rooms at Glasgow required the Ladies to draw Tickets for their places (a phrase that hints that rank based precedence had been abolished, but may not actually mean that).

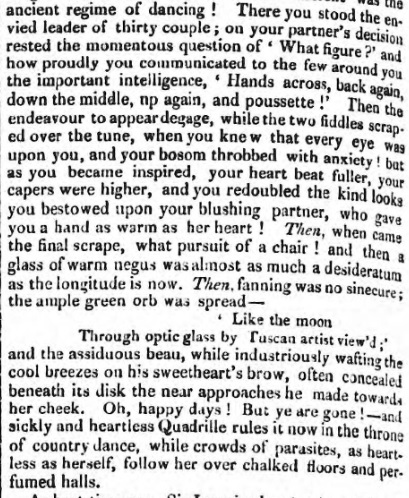

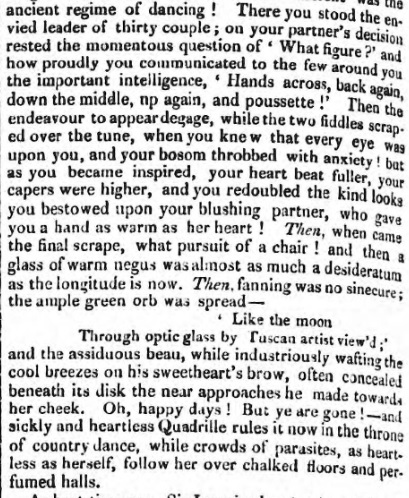

Figure 6. Memories of Calling a Country Dance Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier, 15th February 1827 Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive ( www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

As a minor aside, the Goulding collection of 24 Country Dances for 1788 contains a collection of Twenty-four tunes named to cause amusement when selected; one can imaging the master of ceremonies asking the top couple to name a tune, and the irreverent answer including such Goulding gems as: I'll think of it presently, Something I suppose, I'll tell you by and by or Ask the bottom couple.

The fashionable tunes would vary over time, but dozens were sufficiently popular that they might be confidently requested by the Caller, and any compatible sequence of figures could be selected. Edward Payne noted in 1814 that many dancers struggled to select figures when their turn came to Call, they instead relied on published choreographies; he published his A New Companion to the Ball Room to address that problem, it encouraged dancers to memorise sequences of appropriate figures, and to dance them to any tune with a compatible number of musical strains. The same idea was subsequently championed by G.M.S. Chivers; Thomas Wilson had provided a complex set of tables for similar purposes in 1811.

Wilson, in his 1816 Companion to the Ball Room wrote: It is no uncommon thing to see two or three hundred Persons assemble, for the express purpose of Dancing Country Dances - all of whom are, in their own Opinions, Dancers; and the Majority eagerly contending for the Call, to have the Priviledge of selecting and leading off the Dance, for the purpose of giving the company a Specimen of their Abilities .

This convention of selecting figures was used in many of the Assembly Rooms, but new combinations of tunes and figures weren't necessarily invented. There were a few dances in which the combinations were sufficiently well established that they were almost always danced together. For example, the author of Recollections of Almacks wrote of the complicated figure of Monymusk, and the college hornpipe as though the choreographies for those popular tunes were firmly established amongst the dancers at the fashionable Almack's Assembly Rooms (as they may well have been).

Thomas Wilson mentioned a few Country Dance tunes that were routinely danced with the same well known sequence of figures. A footnote in his 1816 Companion to the Ball Room associated with a tune called Village Maid reports: To this tune, as is likewise the case with Downfall of Paris , Scotch Contention , Rural Felicity or Haste to the Wedding &c. but one particular figure is danced, I have given the original Only as a New figure to these tunes however correct would by dancers in general be considered wrong & never used. . But the clear observation is that most tunes were not danced to a universally acknowledged set of figures; Thomas Wilson in particular often published numerous alternative figures for a single tune. Modern arrangements of those dances might select a specific set of figures for use, or combine several alternative choreographies together to form one longer sequence of figures; but that's a modern approach to Country Dancing, most social dancers 200 years ago didn't memorise long lists of tune-and-choreography combinations - at least until the introduction of the Quadrille (and ignoring a few favourite Cotillions).

Note: a market did exist for books that printed suggested choreographies. Wilson's 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore is the most obvious example, it only contained choreographies, no tunes. If someone bought it, they did so because they wanted Wilson's recommended figures for hundreds of popular tunes. It completely sold-out of its first print run, resulting in a second edition in 1816; we might infer from this that, contrary to the conventions of the Assembly Rooms, many ordinary social dancers did appreciate the security of expertly pre-arranged figures, as danced at Almacks , as the covers of typical Country Dance collections often boasted. If we further consider the number of hand written tune books that include dancing figures (usually produced by musicians for personal use), it becomes clear that the combinations of tunes and figures were important to many people and communities 200 years ago. Even Jane Austen herself is suspected to have made a personal copy of a Country Dance tune called Savage Dance, together with the associated figures.

Wilson included a list of his subscribers in the 1811 Supplement to the Treasures of Terpsichore, their names provide an insight into the type of people who purchased that work; they weren't the Lords and Ladies of Almacks, but a rather more ordinary group, with the occasional Captain or Lieutenant amongst them. We might guess that the confidence to Call a Country Dance was partially associated with social rank, and that Wilson's customers were the type of people who wouldn't have been taught how to Call-like-the-nobility from youth. Presumably they wanted to think that they were dancing like the elite, regardless of whether the typical Country Dance publications were representative of elite dancing or not, and would buy the tune books that purported to tell them how.

Some modern commentators hint that historical Country Dances were rarely danced to pre-selected and published figures. I find that a little improbable considering the many thousands of Country Dances that were published combining both Tune and Figures - I don't believe in an historical conspiracy to confuse modern enthusiasts! It is true, in most cases, that the lead couple at an Assembly couldn't select a tune by name and expect the dancers around them to already know the figures that were about to be Called; but since the purchasers of typical shilling-per-book Country Dance publications were unlikely to have been dancing at the more elite of the Assembly Rooms, there's no reason to think the combinations weren't useful for their intended audiences.

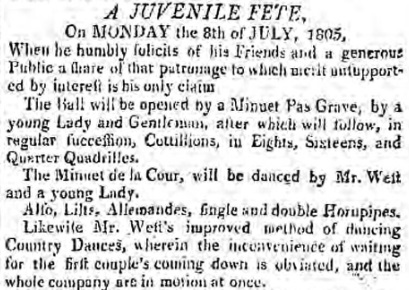

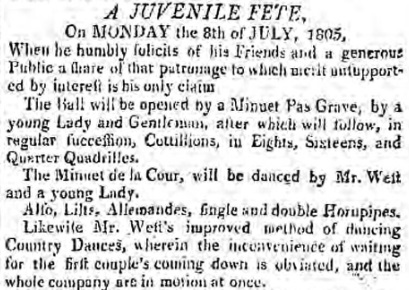

Figure 7. Mr West's innovations for Country Dancing, Derby Mercury, 27th June 1805 Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive ( www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

A nostalgic writer published in the Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier (15th February 1827, see Figure 6) complained of the Quadrille's domination of the Ball Rooms in the mid 1820s, and commented on his fond memories of Calling Country Dances. He wrote: There you stood the envied leader of thirty couple; on your partner's decision rested the momentous question of What figure? and how proudly you communicated to the few around you the important intelligence, Hands across, back again, down the middle, up again, and pousette. Then the endeavour to appear dégagé, while the two fiddles scraped over the tune, and your bosom throbbed with anxiety! But as you became inspired, your heart beat fuller, your capers were higher, and you redoubled the kind looks you bestowed upon your blushing partner, who gave you a hand as warm as her heart! ... Oh, happy days! But ye are gone! - and sickly and heartless Quadrille rules it now in the throne of country dance .

The figures were communicated amongst the dancers at the top of the Country Dancing set, but the dancers lower down the lines had to pay attention and watch the dancers above them, then they would join in when the dancing reached them. There wasn't an amplification system allowing a modern-style caller to announce the figures over the sound of the music and of people talking, nor was there a modern walk-through of the figures prior to the dancing; the dancers at the head of the set would dance the figures that the lead couple had Called, and everyone else would join in when their turn came.

The Simultaneous Start, and Ending a Country Dance

Simultaneously started Country Dances appear to have been a rarity, at least in the elite assembly rooms.

A Dancing Master named Mr West boasted in 1805 (Derby Mercury, 27th June 1805, see Figure 7) that he had invented an improved method of dancing Country Dances, wherein the inconvenience of waiting for the first couple's coming down is obviated, and the whole company are in motion at once . Exactly what he had invented is unclear, what is certain is that he considered it to be valuable. He wanted to keep his new technique secret, his advertisement went on to read: Mr. W desires that no Country Dancing-Master whatever will attempt to come, as he does not wish that any of them should be in possession of more than they already know ! Maybe West was teaching the three-couple set, or a call of hands six to allocate minor sets before the dance began, or perhaps a Circular Country Dance. Whatever his technique was it's probable that many other innovators had independently discovered or invented similar systems for themselves. Indeed, a dancing master from Hull named Mr Southern had published a set of country dances in 1773, the cover of his collection make very similar promises to those of Mr West. West may have unknowingly resurrected the much earlier techniques hinted at by André Lorin in his c.1685 Book of the Contredance, Lorin alluded to several less monotonous and tedious techniques for country dancing (the quoted words are from the Gill Plant translation in the DHDS' journal Historical Dance, Volume 2 Number 2, 1982). However it came to be, West provided one of the first 19th century hints I'm aware of for simultaneously started Country Dances. Mr Southern's similar system from 1773 involved dancing Country Dances in the manner of Cotillons , this seems to have implied memorising the figures for a dance, something that would have been almost unheard of at the time. Perhaps Mr West's system was derived from that of Mr Southern.

We know that simultaneously started country dances were an exotic rarity in the elite ballrooms of the early 19th century. They're ubiquitously danced in the modern world however. If you like to recreate historical Country Dances using the simultaneous start of multiple minor sets, replete with a modern caller announcing the figures as they're danced, you could claim that you're employing an experimental variant of Mr West's (or indeed Mr Southern's) Country Dancing technique!

The courteous way to end the Country Dance varied by date and location, it generally involved the first couple reaching the bottom of the set for the second time, having left the second couple at the top of the set. The chart in Figure 4 demonstrates this. At the end of iteration 37 the second (or B ) couple are at the top of the set for the second time, and no longer take part in the dance. By the end of iteration 45 only couples ALM remain, and the dance ends. It's noteworthy that the dance ends at that point, rather than attempting to have couples L and M progress; this is in contrast to the first time the lead couple reached the bottom of the dance (this early termination was explicitly commented upon by John Cherry, Edward Payne, and by G.M.S. Chivers in their respective ball-room etiquette guides of the 1810s). The end of iteration 10 saw the lead and M couples dancing together without a third couple. In modern terminology we sometimes refer to dancing with a ghost, the ghost being a missing dancer or couple that we pretend is present; if the Figure 4 chart by Cherry is taken literally (and Wilson's equivalent chart from 1820 too) then 200 years ago they danced with ghosts at the bottom of the set on the first pass through the Country Dance, but didn't on the second pass through the Country Dance.

An alternative convention for ending a Country Dance, as promoted by Thomas Wilson in the 1808 first edition of his Analysis of Country Dancing, was for the first couple to dance until they returned to the top of the set, then to dance down a further three places, and for the dance to then end. Wilson continued to promote this ending in his 1816 Companion to the Ball-Room, and in the etiquette guide of his 1820 Complete System of English Country Dancing (despite showing the contrary in the diagram he'd borrowed from Cherry, see Figure 4). G.M.S. Chivers, writing in 1818, wrote that In some Assemblies when the couple who called the Dance, have gone down three the second time, it terminates, which is evidently wrong ; Chivers, in what was probably in reference to Wilson, wrote further on this subject in 1821: some teachers will still persist in their old plan, because they are ashamed to acknowledge their error . Regardless of which of the two conventions were followed, the first couple were expected to start the next dance from the bottom of the set.

Display Dancing for Spectators

I'm lucky to be a member of the Hampshire Regency Dancers, a group who've been blessed with the opportunity to perform Regency era dances at numerous wonderful venues across the South of England. But a question I sometimes ponder is whether display dancing of historical Country Dances is an anachronism.

Most social dancers 200 years ago danced for enjoyment, not to impress an audience. Figure 8 (and Figure 5) shows an image of a typical Regency era Assembly Room, with a suitably disinterested audience. The Country Dancers are enjoying themselves, but the rest of the Assembly go about their business. These dancers are not putting on a performance. The act of display dancing changes a Country Dance; it emphasises synchronicity, steps*, memorised choreographies and graceful embellishments - things a typical Regency era social dancer might not have been especially concerned about. But display dancing isn't a modern phenomenon either, it featured historically in at least two contexts: stage dancing, and at Dancing-Master's balls.

(*) okay, I've added steps into that list to court a little controversy! I'm not convinced that the average social dancer 200 years ago was particularly concerned about precise steps, though the dancing masters certainly were. The dancers were expected to use steps appropriate to the music and dance, but a balletic level of precision wasn't exhibited by most typical dancers.

Professional stage performers often included dancing in their productions, and that could include demonstrations of perfected social dances, along with figure dances and court dances. If a Country Dance was performed on stage, it's likely to have been heavily choreographed. For example, an 1800 advert in the Portsmouth Telegraph (31st March 1800) advertises a new Comedy ... called SPEED THE PLOUGH ... In Act II will be introduced a ploughing match, and Country Dance, by the Characters . An 1816 report in the Chester Courant (20th August 1816) mentions The French have now dramatized the episode of Samson ... Dalilah cuts off his hair in the intervals of a hornpipe, and the Philistines surround and seize their victim during the involutions of a Country Dance . Elite dancers might even perform at a Ball as an entertainment for the guests.

Dancing Masters occasionally produced a ticketed performance event to showcase the talents of their students (and therefore themselves), sometimes referred to as a Juvenile Fete , Pupils' Ball , Dancing Master's Ball or similar. The students, often children, performed for the admiration of their parents and the public. If a Country Dance featured in such a performance, it would probably have been in a choreographed form (see, for example, Figure 7).

Displaying a Regency era Country Dance to an admiring audience is a little anachronistic, but not unreasonable. I imagine that if an important person was dancing 200 years ago (perhaps a member of the Royal Family) a more attentive audience might be expected to politely watch, and the social graces within the dance would be emphasised. Wilson did note in his 1821 The Address that there may be spectators to a Country Dance, and that certain activities would be open to observation and comment. We consider such embellishments to a Country Dance here.

One point that spectators might have noted was the number of dances a particular couple shared together during a Ball. The rules and expectations varied, but many venues required couples to dance no more than two dances together. Edward Payne's 1814 rules at his Assembly were a little more tolerant: It is requested that ... on every second dance a change of partners (except those who bring their partners and wish to continue dancing with them.) . The selection of dancing partners was liable to be noticed. Many venues required the ladies to not refuse an invitation to dance from a legitimate partner, though some were a little more liberal; for example, Kingston Assembly Rooms in 1816 had the rule That it be left at the option of the ladies to dance with whom they please; and their declining any particular partner shall not prevent their dancing with another. The precise rules could vary quite significantly from one Assembly Room to the next, and also over time - the etiquette conventions from the Bath Assemblies of the 1770s might not apply to London's Public Balls in the 1810s. Some Assemblies had very strict rules about which dance individuals were allowed to join; for example, Lord Cockburn in his Memorials of His Time wrote of a convention at the Edinburgh Assemblies of his youth (the late 1780s and 1790s) that partners had to be registered with the Master of Ceremonies prior to the commencement of the Ball:

No couple could dance unless each party was provided with a ticket prescribing the precise place, in the precise dance. If there was no ticket, the gentleman, or the lady, was dealt with as an intruder, and turned out of the dance. If the ticket had marked upon it - say for a country dance, the figures 3.5 - this meant that the holder was to place himself in the 3rd dance, and 5th from the top; and if he was anywhere else, he was set right, or excluded. And the partner's ticket must correspond. Woe on the poor girl who, with ticket 2.7, was found opposite a youth marked 5.9! It was flirting without a license, and looked very ill, and would probably be reported by the ticket director of that dance to the mother.

Country Dancing Variations

London's dancing masters introduced several new variations of the veteran Country Dance, to varying degrees of success, during the Regency era. The table below charts their efforts in so far as the surviving evidence allows. These variants were new, but in most cases they weren't danced by the London public outside of their inventor's Academies and Balls, or those of a few key acolytes (some of these dances only gained recognition in London in the 1830s, they achieved popularity elsewhere amongst dancers who probably thought they were popular in London, and the dances thereby drifted into London over time). The existence of these variants strongly hints that the innovations they promoted weren't being routinely danced prior to the date of first publication; this in turn adds weight to the argument that regular Country Dances weren't danced as duple minors, didn't start improper, and did feature neutral couples.

The idea of experimenting with the form of a dance wasn't new in the 1810s; there had been more variety in the form of the country dance back in the 17th century than in the early 19th century, it's likely that innovators had always played with the conventions too. For example, a writer with the initials F.P. (possibly Francis Peacock) wrote in the 1772 third volume of The Lady's Magazine of a newly invented hybrid dance involving elements of both country dancing and cotillion dancing; this innovation involved what modern dancers might refer to as the Becket formation, two lines of couples standing side by side such that each dancer would have someone of the opposite gender on each side of them and across from them. Two example choreographies were published by F.P., it wasn't a successful format but it demonstrates that individuals were willing to experiment. We've written more about these dances, and other exotic country dancing variants of the late 18th century, in another paper.

Let's consider some of the Regency era variations:

| Country Dancing Variation | Form | Comments |

New Figures, 1811 |

|

Thomas Wilson published a collection of New Figures for Country Dancing in the 1811 third edition of his Analysis of Country Dancing. The first edition of that work had described the old figures in encyclopedic detail, Wilson decided to innovate.

He reported:

As novelty in Dancing as in every other amusement, is the author and promoter of an enlivening vivacity, and invariably affords encouragement to the learners of those sciences, where it may properly be introduced and applied, and knowing full well, that it is equally irksome for good Dancers to be always using the same Figures, as for a professed musician to be continually playing the tune ... and from the repeated suggestions of several good Dancers, and at the particular request of a great number of the author's Friends and Pupils; and in order to answer the purposes of novelty and variety, and to promote and encourage as far as possible the instruction of learners, and the more pleasing amusement of the votaries of Dancing. The author has been induced to compose and arrange a variety of NEW FIGURES, which he submits, as being entirely of his own invention and composition .

His new figures included such examples as The Snake, Round the Corners, The Labyrinth and the True Lovers Knot. Such figures infrequently appeared in Wilson's own published choreographies, and are very rare in non-Wilsonian publications. Their existence does demonstrate an interest in novelty, and that Wilson was considering that need from a relatively early date. The most popular (based on its use in his published choreographies) of Wilson's new figures was his Double Triangle, an example of which can be found in an 1813 dance called The Funny. Other examples include The Maze, as seen in an 1814 dance called The Canterbury Waltz, The Top Couple Cast Off, and Bottom Couple Set and Lead Up, as seen in the 1819 Amateurs and Actors, and Whole Figure Contrary Corners, as seen in The Pigeon. Wilson even choreographed an 1819 dance called La Chasse made up almost entirely of new figures. We've indexed Wilson's new collection of Country Dancing figures here.

|

Spanish Country Dances, c.1815 |

|

The dancing master Edward Payne was promoting this new dance form from about 1815. It's a variation of the regular Country Dance in which the lead couple begin improper (meaning on the wrong side of the set). They're danced in groups of six, much like a regular Country Dance, and use conventional Country Dancing figures renamed in Spanish. They're danced using waltz and promenade steps.

Payne wrote of Spanish Country Dancing in his 1818 Quadrille Dancer:

A Spanish Dance is formed precisely in the same manner as an English Country Dance, except the 1st couple, which commence on the opposite sides, that is the lady begins from the gentlemans side, and the gentleman from the ladies. This rule must be observed by all the couples, when they commence from the top; when they have gained the bottom, they return to their own sides. The couple that called the dance have also the privilege, after going down and regaining the top, to recommence with an other figure.

We've written more about these dances elsewhere. They did achieve some early popularity, and were subsequently promoted by Thomas Wilson, G.M.S. Chivers the Lowe Brothers, and others. There's relatively little evidence of them being danced outside of the Dancing Masters' own balls and academies, though they appear to have been more popular than most other Country Dancing variations in this list.

|

Waltz Country Dances, 1815 |

|

Thomas Wilson introduced what he claimed was a new dance form called Waltz Country Dances ahead of his 69th public ball in 1815. This ball at the New London Tavern was, he claimed, the first time they were publicly introduced (based on an 1821 advert in Wilson's The Address).

He also published choreographies for Waltz Country Dances from 1815, one of the first examples being in his Le Sylphe collection for 1815. I don't know of any surviving Wilsonian texts that describe the Waltz Country Dance in detail, though a footnote in his 1816 A Companion to the Ball Room indicates that he was working on such a book.

What is clear is that he intended the Waltz Country Dance to be a fusion of Country Dancing and Waltzing, something more than a mere Country Dance in waltz time (of the type that had been danced from at least the early 1790s). He used such figures as Turn a-la Waltz and Pousette with Sauteuse Step. Many modern interpretations of earlier Country Dances in Waltz time use these same figures, but Wilson considered it to be a new dance form of his own invention in 1815. An example Waltz Country Dance can be seen in the 1818 Belcéle.

|

Ecossoises, 1817 |

|

The Ecossoises were Thomas Wilson's answer to the Spanish Country Dances. Wilson published his Ecossoise Instructor in 1817, and went on to feature this new dance form in public at his 76th Ball in March 1818. He claimed that the dance came from Russia by way of France, but as far as I can tell he'd basically invented them himself (though a different dance with a similar name was being danced in Germany at this time).

As with the Spanish Country Dances, the Ecossoises are danced with the first couple starting improper; the major difference is that they're danced in groups of four (that is, as duple minors). Wilson wrote:

Though the ECOSSOISE are constructed somewhat similar to English Country Dances yet in their formation they also partake in a great measure of what is termed the Spanish Contra Dance tho' differing entirely from that Dance both in figures and steps.

The figures are less complex from their being shorter than those of the English Country Dance, the respective Minor sets in the Dance being formed of but 2 couples instead of 3 the number required in English Country Dancing.

|

Swedish Country Dances, 1818 |

|

G.M.S. Chivers introduced his Swedish Country Dances from 1818. He freely admitted that they had nothing to do with Sweden, he just liked the name. His major innovation over the regular Country Dance was that they were danced in columns of three rather than two, and omitted the neutral couples.

He wrote the following in his 1821 Dancer's Guide:

This species of dancing may be performed by a majority of either sex, or an equal number of ladies and gentlemen ... Every person has their face towards the top except the top three (or line) who face the bottom, which each line takes in succession.

Each Dance begins with the two top lines, and when there are two lines clear, they commence again at top, and so they continue until all have been down it. The number of persons is unlimited.

|

Circular Country Dances, 1818 |

|

Thomas Wilson introduced his Circular Country Dances in 1818; he published his A New Circular System of English Country Dancing that year and featured them in his 77th public ball (held at the Crown and Anchor Tavern, April 1818). We've written more of this publication elsewhere, you might like to follow the link to read more. The innovation over regular Country Dancing was at least twofold: the longways set was bent around into a circle and minor sets were pre-allocated and simultaneously started. A less certain innovation, if one reads between the lines, was that multiple different country dances may have been danced around the circle simultaneously.

Wilson wrote:

The Author has been induced to present this Plan to the Public, not only to save time in the performance of the Dance, but also to enable a whole Company to commence the Dance at the same time, so as to completely obviate the long-complained-of fatigue of sometimes standing up a considerable time inactive Gazers, before they get to the Top of the Dance, or into motion; which often induces persons to-quit the Dance (contrary to Etiquette) before it is finished.

In Wilson's circular system every third or fourth couple were denoted to be a leading couple and could select whatever figures to dance they pleased, a neutral couple would be required between each minor set. A half dozen different sets of figures might thereby be danced around the circle simultaneously to the same tune, as soon as a couple progresses above a leading couple they would have to watch the new first couple who would be progressing towards them in order to discern the new set of figures to dance.

This format may have inspired other circular dance variants such as Mr Bemetzrieder's c.1820 Circassian Circle and G.M.S. Chiver's c.1822 Chivonian Circle.

|

Quadrille Country Dances, 1819 |

|

Thomas Wilson introduced his Quadrille Country Dances in 1819; they featured in his 79th Public Ball (in April 1819), and were to be the subject of an 1820 publication called The Quadrille Country Dance Preceptor (it may not have been published). Wilson asserted that he had invented this dance form.

The dance involved a fusion of ideas from both Quadrille dancing and Country dancing. I'm not aware of many surviving Wilsonian Choreographies, or any extant copies of his explanatory book. It's likely to have involved two columns of dancers, as normal, but with the couples facing each other in pairs as in a Quadrille. The dances involved a mixture of both Quadrille and Country Dancing figures, and ended with a Country Dancing progression. An example Quadrille Country Dance choreography can be found in Wilson's 1824 The Wrestlers.

|

Mescolanze, 1819 |

|

G.M.S. Chivers introduced the Mescolanze from 1819. They extended the concept of the Quadrille Country Dance by using columns of four rather than two. Two lines of four dancers face each other and dance Quadrille figures, ending with a Country Dance progression to meet a new line of four. There were no neutral couples (as with Chivers' Swedish Country Dances).

Chivers wrote in his 1821 Dancer's Guide:

The Mescolanze (i.e. a Medley Dance) is a species of dancing adapted either for large or small parties, that is from sixteen persons to any number can join.

Every person has their face towards top excepting the top four or line (who face the bottom), which each line takes in succession.

... Each Dance begins with the two top lines, and when there are two lines clear they commence again at top, and so they continue until all have been down it.

Observe to place the lady on your right when you get either to top or bottom.

|

L'Unions, 1821 |

|

G.M.S Chivers introduced his L'Union Dances from 1821, they're related to both the Quadrille Country Dances and the Ecossoises, and retain neutral couples between the minor sets. Chivers described them in his 1822 Modern Dancing Master as:

L'Union Danses can be performed by any number of persons, observing that the first lady goes down the side that the gentlemen stand on; and that the first gentleman goes down the side that the ladies stand on; and when they get to the bottom they take their own sides; so that you lead down one side the same as in a Contre Danse; then exchange places and lead up the other.

As each couple get to the top, the lady and gentleman exchange places, and go down the Dance the same as the first couple.

When the first couple have gone down three couple, they commence at top; and so they continue leading off every three couple; and each Dance finishes when all have been down it.

|

Conclusion

Country Dancing could take many different forms in the Regency era. Figure 9 depicts the organised chaos of a Country Dance in motion and clearly being enjoyed by the assembled company. Thomas Wilson summarised some of the rich diversity to Country Dancing in the introduction of his 1820 Complete System of English Country Dancing, a condensed (significantly edited for brevity) version of which appears below. His essay celebrates the nature, extent, and variety, of which Country Dancing consists ... they are self-evident truths , and are intended to afford a stimulus to closer application in the study of his work as well as to convince those persons of their error who hold Country Dancing as a simple, trifling art, very easily attained . The essay is almost a poem, it includes the following stanzas (page 3):

A Dance may be set with either two, or twenty Figures.

A Dance may be set so as to actively employ the company.

A Dance may be chosen, that will keep the whole company in motion, or one that renders two thirds of the couples inactive.

A Dance may be chosen, where all the Figures except one finish on the wrong side.

One Dance may contain but one progressive Figure, or set with four, and both equally correct.

A Dance may be formed wholly of Gentlemen, or wholly of Ladies; or

of an equal number or certain portion of each.

A Dance may be formed, that will require an hour for its performance; and one may be formed with the same music, that may be completed in five minutes.

A Dance may be set so very easy, that its Figures may be performed by a person never having before attempted; or Set so difficult and complex, as to require all the skill of a good Dancer.

A Dance may be formed to contain ten neutral couples; and to the same tune, One may be composed so as not to contain one neutral couple.

A Dance may have fifty couples in motion at the same time, or only one, and both be equally correct.

A Dance may be chosen, in which the hands of the partners may not be disjoined; and another set, in which the partners never join hands.

A Dance may be set with only three couples.

A great variety might be given in addition;

We'll end our investigation into the form of Regency era Country Dancing here. By way of conclusion please remember that Country Dances, be they historical or modern, are primarily danced for fun; so please do enjoy them. As usual, please do contact us if you have further information to share; we love to be informed about additional evidence for informing the interpretation of historical social dances.

|

Figure 1. The form of a Country Dance, A Treatise on the Art of Dancing in the Ball Room, John Cherry, c.1813

Figure 1. The form of a Country Dance, A Treatise on the Art of Dancing in the Ball Room, John Cherry, c.1813

Figure 2. Extract from Wilson's Plan of a Country Dance, 1820

Figure 2. Extract from Wilson's Plan of a Country Dance, 1820

Figure 3. Extract from Wilson's Plan of a Country Dance, 1820

Figure 3. Extract from Wilson's Plan of a Country Dance, 1820

Figure 4. Cherry's c.1813 Plan of a Country Dance, and Wilson's c.1820 The Progressive Motion of a Country Dance

Figure 4. Cherry's c.1813 Plan of a Country Dance, and Wilson's c.1820 The Progressive Motion of a Country Dance

Figure 5. Rowlandson, More Miseries, 1807

Figure 5. Rowlandson, More Miseries, 1807

Figure 6. Memories of Calling a Country Dance Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier, 15th February 1827

Figure 6. Memories of Calling a Country Dance Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier, 15th February 1827 Figure 7. Mr West's innovations for Country Dancing, Derby Mercury, 27th June 1805

Figure 7. Mr West's innovations for Country Dancing, Derby Mercury, 27th June 1805 Figure 9. A Country Dance, Rowlandson, c.1795.

Figure 9. A Country Dance, Rowlandson, c.1795.