| Return to Index | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

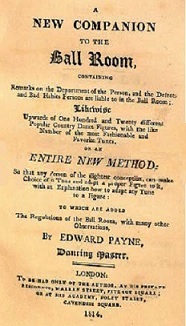

Paper 9 Edward Payne, Dancing Master (1792-1819)Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 25th November 2014, Last Changed - 20th March 2021]Edward Payne was one of the most influential Dancing Masters of Regency London. He was a band leader, publisher, choreographer and inventor. He was closely involved in popularising two social dancing movements, the First Set of Quadrilles, and the Spanish Country Dances. He also pioneered the use of a new barrel organ for Quadrille dancing. Yet he remains relatively unknown; even two hundred years ago he was readily confused for his better known contemporary, James Paine of Almack's. This paper investigates his life and works.  Figure 1. Payne's 1814 New Companion to the Ball Room

Figure 1. Payne's 1814 New Companion to the Ball RoomImage © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, C.193.a.109 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED This project has been limited by a lack of evidence. I know almost nothing of Payne's life prior to 1814; he died in early 1819 (or in late 1818), almost everything we have covers just five years of his professional career. In that time he published at least three books on dancing, eleven sets of Quadrilles, three sets of Spanish Country Dances, and some Waltz tunes. But he remains a mystery. Update: A reader has been kind enough to contact us with additional biographical details for Payne. I am indebted to Nick Skelton for the following details (and for some associated documentation omitted here, courtesy of Ancestry.com):

A New Companion to the Ball Room

An advertisement in the Morning Post newspaper, for December 1st 1814 reports The following sheets are extracted from a Treatise on the Art of Dancing, which I had nearly completed twelve months back; but, in consequence of my time being so much occupied, I was prevented from drawing the Work to a close. Several of my Pupils who have seen it, (and were acquainted with the cause of its delay,) have earnestly requested me to select the following part for immediate Publication, (which is not more than one Quarter of the work, even in its present unfinished state.) The distinguished Patronage and flattering reception I have already met with from my honoured Pupils, have induced me to comply without hesitation with their request. The book was made up of three parts: a treatise on deportment, Payne's system for constructing Country Dances, and a review of the etiquette of the ball room. The essays on deportment and etiquette share a striking similarity to the equivalent essays published by the better known dancing master Thomas Wilson in his similarly named 1816 Companion to the Ball Room and elsewhere. It's likely that Payne's book was partly derived from Wilson's earlier works, and that Wilson's later works were partly derived from Payne's book. Both authors ultimately shared a common source in Richard Nash's 18th century regulations for the Assembly Rooms at Bath, and also with the regulations imposed by the many Assembly Rooms across Britain. We've discussed these issues in another research paper.

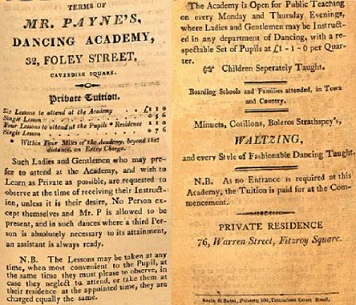

Payne's It often occurs with Ladies and Gentlemen who are in the habit of attending Balls and Assemblies, (some of whom may be termed good dancers,) that when it comes to their turn to lead off the dance, they find themselves at a loss to form a figure and adapt a Tune to it, although perhaps acquainted with a variety; others again, after much hesitation, find themselves at a loss, and at last are obliged to advise with other couples.  Figure 2. Terms of Mr. Payne's Dancing Academy, 1814

Figure 2. Terms of Mr. Payne's Dancing Academy, 1814Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, C.193.a.109 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Payne then observed that other writers had attempted to address this problem before. This comment may have been a veiled reference to Thomas Wilson's 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore (the sub-title of which happened to match the title of Payne's book). He continued: All the publications of this kind that I have seen, are on an entirely different plan from this; most of them have a figure and a tune set together, some may like the tune and not the figure; others again, may like the figure and not the tune; but as they are set, so they are induced to suppose they must be danced, as I have frequently witnessed. Payne's solution involved counting the number of strains of music in each of the popular Country Dancing tunes, and grouping them together into pools; he had a pool of two-part tunes, a pool of three-part tunes, and so forth; he also choreographed around 120 sequences of dancing figures, these were similarly grouped by the number of strains of music they required. Dancers could match any tune to any compatible set of figures, resulting in a near infinite variety of combinations. The major characteristic of this system is that there would not be a specific set of figures for a specific tune; the same figures could be danced to many different tunes, the same tune could be danced with many different figures.

The benefit of this system is reasonably clear. With a little effort a dancer can invent a new combination of tunes and figures, without having to be an expert. This approach to the

Payne's Academy

Payne operated a Dancing Academy from his premises at 32 Foley Street, Cavendish Square. His December 1st 1814 advert in the Morning Post indicates that he taught A further notice from within the book indicates that he: ... had the Honour of Teaching, and still continuing to Teach in some of the first Families and Schools in the Metropolis, and its Environs; whose Sanction and Patronage he may justly boast of and meeting every where, with the most flattering Encouragement, as upwards of Four Hundred and Fifty Pupils within the last Four Years can attest; ...

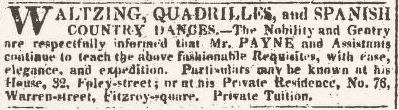

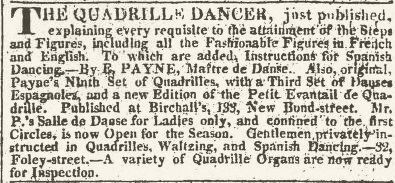

He went on to explain that his former plan to build  Figure 3. Payne's Advert, The Morning Post, 27th May 1816.

Figure 3. Payne's Advert, The Morning Post, 27th May 1816. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

By 1815, he was advertising his

Payne had also published a collection of Six Favorite Waltzes, as played at his Academy & the Nobility's Assemblies, probably around mid 1816; these waltzes were named after the Quadrilles of his First Set, perhaps making it the first Waltz Quadrille to have been published in Britain. The cover of this publication referred to three sets of Quadrilles as being available for purchase

An 1817 advert in The Morning Post (4th June 1817) added that

By 1818 he was referring to his academy as the

Payne's Band and Assembly

Several of Payne's adverts mentioned that he could provide a band, including his 29th April 1816 advert in the Morning Post, which promised Payne also hosted Assemblies of his own. He printed the by-laws for his Assembly in his 1814 A New Companion to the Ball Room, they were: Rules to be observed at this Assembly:A footnote indicated that the 7th rule had recently changed, for the previous four seasons the change of partners was to have taken place after the third dance. These rules are similar to those of Britain's other Assembly Rooms, though there are several distinctive features. We've explored these issues further in another research paper.

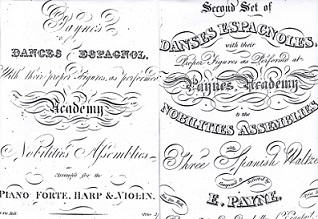

Spanish Country Dances Figure 4. Payne's first two sets of Spanish Dances, c.1817

Figure 4. Payne's first two sets of Spanish Dances, c.1817Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(9.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Danses Espagnoles, the third in 1818 (see Figure 8), and the first two in late 1817 or early 1818 (dated by reference to his Quadrille Fan, see Figure 4). He also included Instructions for Spanish Dancingas a suffix to his 1818 Quadrille Dancer.

We've investigated the concept of It's not clear when Spanish Country Dances first entered Payne's repertoire, the 1816 advert hints that he'd been teaching them for perhaps a year. The absence of references to them in A New Companion to the Ball Room suggests they didn't exist in 1814. Payne was probably the first dancing master in London to teach these dances. Thomas Wilson also published a minor work on Spanish Country Dances in 1817, and G.M.S. Chivers published his Recueil de Danses Espagnole in 1819 (shortly after Payne's death, though he'd been teaching them since at least 1818). Some sources suggest that Nathaniel Gow was promoting Spanish Country Dancing in Edinburgh from as early as 1810, but I've not found any contemporary evidence to support this early date. I can only find one example published by Gow, and that was probably published in 1817 (certainly no earlier than 1816). Spanish Country Dances are very similar to English Country Dances, the key differences are that the first couple begins improper (the man on the lady's side of the set, and vice-versa), and the dance flows like a waltz country dance. The music and figures are effectively the same. Payne explained some of the figures as follows: The Author may be censured, perhaps, for not being more particularly explicit in his explanations. The word 'Engano', imports deceit; 'Latigo', a whip; 'Espejos', a Looking-glass; but translation can be of little avail to those unacquainted with the method of performing the figures. A little practice, however, will easily supply any additional information that may be wanting, which the Author, upon application to him, will readily give.

The figures Payne published were written in Spanish, hinting that the dances genuinely did derive from Spain. A passage from John Carr's 1811 Descriptive Travels in the Southern and Eastern Parts of Spain and the Balearic Isles, in the year 1809 explains the Spanish style a little further. He wrote Payne's 1818 Quadrille Dancer contained an extended description of Spanish Country Dancing. It described the construction of a Spanish Dance, the steps, an explanation of the Figures and a translation of the Spanish terms. The information in this work is consistent with, but different to, the 1819 Recueil de Danses Espagnoles by G.M.S. Chivers. The diversity of information hints that Payne did not invent Spanish Country Dancing, but may have been the first to document it. The preface to Payne's Instructions for Spanish Dancing adds: [The author]has already Published a first and second set of Danses Espagnoles or Spanish Country Dances, both of which, by a rapid and extensive sale, received the most unequivocal proofs of public approbation. This flattering consideration combined with the numerous and urgent entreaties of many Ladies and Gentlemen calling for additional and diversified examples of these favorite Dances, have induced him to present the Public with the following, these Dances have now become so popular, and their characteristic distinctions are so fully explained in the Authors former sets, that any further remarks here on these Topics, might well be deemed superfluous.

Prior to Payne's adverts, the term

Whatever their origin, they were an unusual variation of Country Dancing that was enjoyed in Britain for the next few years. The anonymous author of the 1823 The Etiquette of the Ball-Room by A Gentleman briefly mentioned that they were danced at the most prestigious London venue, Almack's Assembly Rooms:

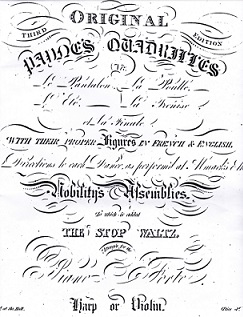

Figure 5. Original Payne's Quadrilles, third edition

Figure 5. Original Payne's Quadrilles, third editionImage © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.925.w.(18.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Payne's First Set of QuadrillesWe've discussed the introduction of the First Set of Quadrilles in a previous paper. The figures of Payne's First Set (see Figure 5) went on to be danced in most Quadrilles for the rest of the 19th century. Payne probably published his First Set of Quadrilles in 1815, certainly no no later than 1816. I own a first edition copy that was printed on paper watermarked for 1815, it has been shared on-line here. An advertisent in The Morning Post newspaper (21st September 1816) mentioned the existence of Payne's 4th Set of Quadrilles, the first three must therefore have been published prior to that date. The 1816 advert in Figure 3 hints that he had been teaching Quadrilles for perhaps a year, though once again, the absence of references in A New Companion to the Ball Room hints that they weren't in his 1814 repertoire (unless he considered the Quadrille to be a type of Cotillion, which is entirely possible, and perhaps quite likely). An 1815 date of initial publication seems most probable. At least three editions of Payne's First Set were published; I've studied the third edition (see figure 5) and the first edition. The two copies share most of the same content, but differ in a few respects: the music for the La Finale quadrille differs between the editions, the first edition includes a brief primer, and the figures of the L'Ete and Poulle quadrilles are slightly different.

The anonymous author of the 1823 The Etiquette of the Ball-Room reported that Quadrille dancing in England was muted during the wars with France: Payne's First Set consisted of Quadrille dances and tunes named Le Pantalon, L'Été, La Poulle, La Trénise and La Finale; you can learn how to dance them here. It's not clear where Payne sourced his music and figures, but the origin myth that links them with the Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Hullin could be correct. Hullin published several works on Quadrille dancing in Paris, some of which feature figures similar to those of the First Set. For example, the figures to his c.1798 L'Elisé are very similar to those of Pantalon; Hullin's La Polimnie has similar figures to L'Été, and so forth. The British troops in Paris and Brussels are known to have danced Quadrilles in 1815, they may have brought a taste for them back to Britain; many early British Quadrilles had names themed around the Battle of Waterloo, they could have ultimately derived from the dances of Hullin. The early history of the Quadrille as a dance form in England is rather more complicated however, Cotillions and French Country Dances (that were Quadrilles in all but name) were sometimes danced, and an earlier dance called the Quadrille was danced in the late 18th century; we've written more on these subjects in another paper.

In his 1818 Quadrille Dancer Payne mentioned that he had recently visited Paris, he implied that this is where he'd collected his dances; other potential sources can't be ruled out however. For example, the London based dancer Michael Kelly published his Eight French Country Dances c.1804. This collection of primordial Quadrilles was published before the term

As we saw in Paper 3, the Quadrille dance was known in London prior to the introduction of Payne's First Set, but they didn't receive wide recognition until 1816. A report of Lady Heathcote's Ball in The Morning Post (22nd July 1816) reads

It's an odd coincidence that one of the Orchestra leaders at the fashionable Almack's Assembly Rooms was the similarly named James Paine. Paine went on to publish his own First Set of Quadrilles in 1816 using (effectively) the same figures as Payne. Payne and Paine independently published numerous Quadrille Sets, their individual identities were frequently confused by both contemporary and subsequent commentators. The potential for confusion is quite obvious,

As an example of the confusion, consider the witty

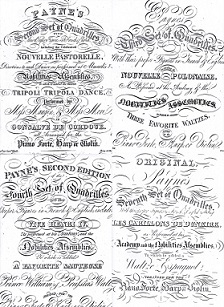

Figure 6. Four sets of Payne's Quadrilles, c.1816-1817

Figure 6. Four sets of Payne's Quadrilles, c.1816-1817Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.925.aa.(13.), h.925.aa.(14.), h.925.c.(5.), h.925.c.(6.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Payne's Quadrilles

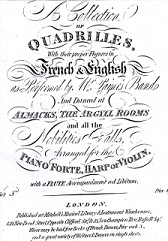

The c.1815 First Set were tremendously successful, Payne followed that publication with many more collections over the next few years (see Figure 6). The Edinburgh based dancing master Barclay Dun wrote in his 1818 A Translation of Nine of the Most Fashionable Quadrilles that the Quadrilles Aside: Perhaps the best clue that Dun worked from a copy of Payne's 1818 Quadrille Dancer (or, perhaps from his 1816 Quadrille Instructor) can be found by studying the figures of Payne's Second Set. Payne published at least three editions of the Second Set between c.1816 and c.1817, all three of which shared the same figures as the First Set. The version in the 1818 Quadrille Dancer is different. The Quadrille Dancer figures were actually those from Payne's c.1817 7th Set, potentially linked to the Second Set by a printing error (the figures for the 7th and 2nd sets appear to have been transposed). Dun's version of Payne's figures match those from the Quadrille Dancer. It is of course possible that Payne published a 4th edition of his Second Set that introduced the new combination of tunes and figures, but it's also possible that they were introduced by error for the first time in the Quadrille Dancer (or perhaps in the Quadrille Instructor). Whatever the provenance, Dun somehow came to print Payne's later arrangement of the Second Set.The provenance of Dun's work is relevant as it's Dun's version of Payne's Quadrilles that are best known today. The figures for Payne's first six sets are readily available for modern enthusiasts to study thanks to Dun, albeit with a few errors of the type noted above. A small c.1817 Quadrille Preceptor was also published by Charles Wheatstone (it's potentially the otherwise lostQuadrille Instructor written by Payne himself, of which no authenticated copies are known to exist); Wheatstone's book is also available on the web, it includes both the figures and music for the first four of Payne's Quadrille Sets (including the later figures for the Second Set and Fourth Set from Dun and the Quadrille Dancer). Payne published at least 11 Sets of Quadrilles before 1819. His 4th Set was advertised in 1816 (The Morning Post, 30th August 1816), the 9th Set in 1818 (The Morning Post, 5th February 1818), and the 10th Set also in 1818 (The Morning Chronicle, 13th May 1818). He also published two books on Quadrille dancing, the 1816 Quadrille Instructor (advertised in The Morning Post, 21st September 1816), and the 1818 Quadrille Dancer (advertised in The Morning Post, 11th March 1818, see Figure 8). Payne published his Quadrille Fanin 1817 containing all the Fashionable Figures(advertised in The Morning Post, 4th June 1817). It was named in French as Un Petit Evantail de Quadrille. His preface to the Dances Espagnol indicate that 1400 of them had been sold. An advert in the 1818 Quadrille Dancer indicates a second edition was available. This fan listed the figures for his Quadrilles, it would have been a useful accessory for any ball-goer who struggled to memorise the choreographies.

It's notable that Thomas Wilson, another Regency era dancing master, also published a work called the Quadrille Instructor in 1816, and went on to publish a Quadrille Fan in 1822. It's likely that Wilson was inspired to follow Payne's lead. James Paine also published a Quadrille Fan in 1817. Payne went on to emphasise that his Quadrille Fans

Payne's 1817 adverts emphasised his role as If the art of Dancing has been improved by rule, or extended by variety, the Author of this work, by study and taste, will be found to have contributed largely to both. The increased and increasing estimation in which the elegant accomplishment of dancing is held, is in a great degree to be attributed to the present knowledge of Quadrilles, which he was the first to publish with their proper figures in French and English, and directions to each dance as performed at the assemblies of the Nobility.

He repeated this claim in his 1818 Quadrille Dancer indicating Payne, along with many of his contemporaries, allowed the figures of his Quadrilles to be sold as miniature cards. Dancers could purchase a collection and carry them with them to a Ball, using them to remind themselves of the figures. Such cards typically measure an inch by two inches (or thereabouts) in size, and can be carried in a reticule for use at a Ball. At least 5 editions of the cards were printed, based on an advert in Payne's 1818 Quadrille Dancer.  Figure 7. An unofficial edition of Payne's 3rd Set. Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.925.aa.(12.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Figure 7. An unofficial edition of Payne's 3rd Set. Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.925.aa.(12.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

If Payne's Quadrille cards and other publications are included, he claimed that

Most of Payne's official works were published through Birchall's Music Shop, though some were published through C. Christmas's Opera Music Saloon. Figure 7 shows what was probably a rogue edition of Payne's 3rd Set of Quadrilles published by Mitchell's Musical Library & Instrument Warehouses. This unofficial edition didn't promote Payne's Academy, it only described the Quadrilles as being A further example of Payne's Quadrilles being republished can be found in the 1st Set of the Favorite French Quadrilles, published in Edinburgh in 1817 for Nathaniel Gow. This collection reproduced Payne's First Set verbatim, note-for-note; the only difference being that Payne's Trenise quadrille was replaced with Gow's La Gertrude. The following table lists the names of Payne's Quadrilles, as recorded in his 1818 Quadrille Dancer. He provided the names below in both French and English. In some cases there are minor differences compared to the earlier publications, such as the suffixed La Pastorale dance in his First Set, or alternate spellings of some of the names. Payne's 10th and 11th Sets were issued after the publication of the Quadrille Dancer.

Payne's Quadrille Organ

Payne's 1817 advert in The Courier (2nd July 1817) advertised a new Quadrille Organ:

The Barrel Organ was, according to Wikipedia,  Figure 8. Payne's advert, The Morning Post 11th March 1818.

Figure 8. Payne's advert, The Morning Post 11th March 1818. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk) It's not clear how popular such mechanical instruments were, but Dancing Master Allen advertised a similar device from 1817 (The Morning Chronicle, 3rd December):

A perhaps similar device called a Cylindrichord was sold by Courcell from 1825. It was said that Payne included a more verbose advert for his Organ in his 1818 Quadrille Dancer. It reads: Mr. Payne, has the pleasure to announce to the Nobility and Gentry, that he has invented an Organ, which plays with the greatest precision a complete set of Quadrilles, without shifting the Barrel, having the effect of a Band; the Richness and Briliancy of its tones, and the admirable quality of keeping in tune, not only renders it a most valuable acquisition to the lovers of Quadrille Dancing, but also an elegant appendage to the Drawing-Room, possessing in its appearence something of the elegance and uniformity of a Cabinet Piano Forte. Barrels may be set which have an excellent effect; containing Spanish Dances, Waltzes, Country Dances, Sacred Music or the most difficult pieces, from the extent of scale, requisite to perform Quadrilles. This instrument is well adapted for the East or West Indies, its construction being so compact and solid, that it resists any Climate.

An Irish advert (Saunders's News-Letter 1st May 1818) mentioned that the organ

I've not found any further information on Payne's Organ, such as Patents, or the nature of his improvements, beyond what he announced in his adverts. At least two of his Organs remained unsold at the time of his death in 1819. An advert in The Morning Post (26th February 1819) advertising the disposal of Payne's assets mentions

Another dancing master, G.M.S. Chivers advertised his own

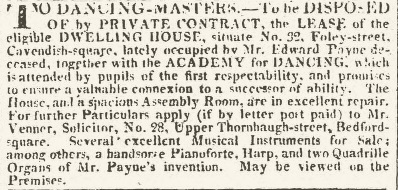

Payne's DeathPayne died either at the end of 1818, or the start of 1819, just as the Quadrille was rapidly growing in popularity. He didn't get to experience the full success of his dances. He was buried on the 15th February 1819, a subsequent notice in The Morning Post (26th February 1819, see Figure 9), announced the disposal of his assets: To Dancing Masters - to be Disposed Of by Private Contract, the Lease of the eligible Dwelling House, situate No. 32 Foley-street, Cavendish Square, lately occupied by Mr. Edward Payne deceased, together with the Academy for Dancing, which is attended by pupils of the first respectability, and promises to ensure a valuable connexion to a successor of ability. The House, and a spacious Assembly Room, are in excellent repair.

A month later The Morning Post (12th March 1819) reported the auction of Payne's academy. They describe it thus:  Figure 9. Disposal of Payne's possessions, The Morning Post 26th February 1819.

Figure 9. Disposal of Payne's possessions, The Morning Post 26th February 1819. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk) A subsequent notice in The Morning Post (8th June 1819) contained a message from Payne's mother: Elizabeth Payne embraces the earliest opportunity of returning her sincere and grateful Thanks to the Nobility and Gentry, for the very liberal encouragement and support experienced by her Son, Edward Payne, late of Foley-street, near Cavendish-square, Dancing-Master, deceased. Mrs. Payne earnestly solicits all Persons having any Demands upon his Estate, to deliver her the particulars, that she may examine and discharge the same; and all Persons indebted to his Estate are requested to pay the amount to her.

Another dancing master named W. Payne described himself as a Professor of Dancing and Fencing in Salisbury in the 1820s (Salisbury and Winchester Journal, 27th January 1823); this new Payne may have been related to Edward Payne, and perhaps continued his legacy. He had a similar repertoire, including Edward Payne's name continued to be associated with Quadrille dancing for decades to come, even if he was often confused with his contemporary James Paine. He experienced a meteoric success in the 1810s, who knows what might have happened had he lived a little longer?

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved