|

Paper 23

La Batteuse, a Figure Dance

Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor

[Published - 1st August 2016, Last Changed - 9th April 2025]

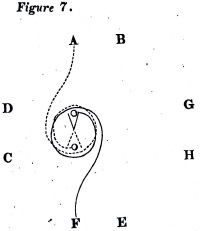

La Batteuse (also known as La Bateuse or La Batteause) was a social dance that achieved a moderate degree of popularity in London during the Regency era, and was the subject of an entire work published in 1817 by the dancing master Thomas Wilson (see Figure 7). It was a square dance related to the Quadrille but it featured an unusual musical arrangement in 10-bar strains. It was referred to as a figure dance and would showcase the talents of the dancers who performed it. In this paper we'll consider the story of this distinctive dance and how it was performed.

But first we'll investigate the concept of Figure Dancing.

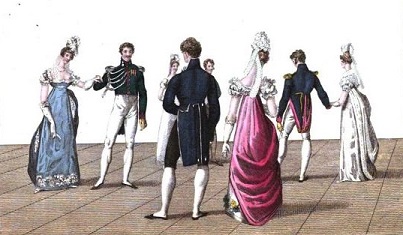

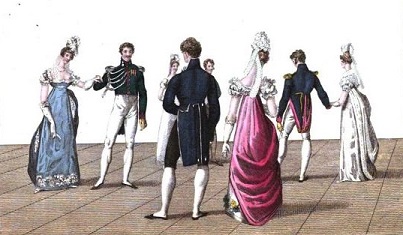

Figure 1. Illustration for the 1820 L'Horatia figure dance from Belle Assemblée

Figure Dancing

Some early references to La Batteuse described it as a Figure Dance. This term was applied to a wide range of choreographed dances, their distinguishing characteristic being a need for the dancers to know the figures in advance of their performance. Figure dances were distinct from the unchoreographed Country Dances that were the staple of London's Ball Room dancing at the start of the 19th Century. The concept of a figure dance was sufficiently broad to include solo dances, couple and trio dances, or involve an entire team of performers. The term was often applied in social dancing to refer to the French style of Cotillion dancing introduced to Britain from the mid 1760s, and to its successor in the late 1810s, the Quadrille.

Many early references to the Quadrille dance described it as a figure dance; British quadrille dances of the Regency era featured complex choreographies and step sequences for the dancers to learn and then memorise. For example, the Duchess of Devonshire hosted a Fancy Dress Ball in 1811 in which the dances are to chiefly be figure dances, such as Quadrille, French Cotillions, and Waltzes (The Morning Post, 6th June 1811). In 1817 the Devonshires hosted a Ball for the Grand Duke of Russia in which the celebrated French figure dances were then introduced called Quadrilles (The Morning Post, 5th February 1817). Figure 1 is an 1820 image from Belle Assemblée magazine showing a Figure Dance to the Quadrille music of L'Horatia , the associated dancing figures were those of a typical Quadrille.

Figure dances could be challenging for many social dancers, the abundance of popular Quadrille choreographies required significant effort in order to memorise the figures. Modern Regency dancing enthusiasts are often encouraged to memorise sequences of figures, but this wasn't a characteristic of typical social dancing two hundred years ago... except with the figure dances.

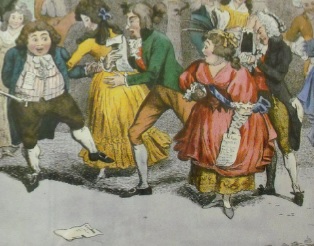

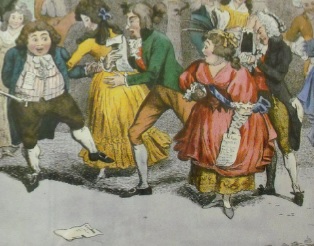

A tactic sometimes employed to help the dancers was to hold a practice session ahead of a public Ball; for example, the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette for 12th February 1818 advertised a subscription Ball, and added that The music will attend at the Rooms on Monday preceding the Ball, at one o'clock, for the Quadrille practice . Figure 2 shows a Cotillion dance being rehearsed in 1792, the dancers each have sheets of instructions, presumably listing the figures of the dance. Another tactic was to sell lists of choreographed Quadrille figures on Cards and Fans, dancers could keep these cheat-sheets with them during a Ball; this technique was popular from the mid 1810s to the mid 1820s. This trend for variety and new choreographies drifted to an end in the mid 1820s, new Quadrille Choreographies were rarely published thereafter. Figure dances, in the form of Quadrilles, were a major part of the social dancing experience in Britain from around 1816 to 1824; Quadrilles remained popular thereafter, but only a few favourite choreographies were widely used, most notably those of the First Set. The Lowe brothers in the 1831 third edition of their Ball Conductor and Assembly Guide wrote about another strategy for assisting social dancers: Calling ; they wrote that it is usual for the master of the ceremonies, the leading musician, or some one, to call the figures during the performance of Quadrilles . A convention of prompting or announcing the figures to be danced prior to dancing a Quadrille was common in Britain across the 1820s, prompting the figures during a Quadrille dance may have been a new convention for the 1830s.

Figure 2. Detail from a 1792 Print called Rehearsing a Cotilion; the dancers have sheets of paper with instructions

The term figure dance can be quite useful. Some historical terminology is easily misinterpreted; important terms such as Cotillion and Quadrille had meanings that changed over time, this has the potential to confuse the interpreters of the historical record. For example, it's all too easy to take a late 1810s understanding of the word Quadrille and apply it to a 1790s use of the word. The term figure dance is useful as it isn't encumbered with anachronistic expectations. It's a generic term that was used since at least the 17th Century to describe choreographed dancing, it encompasses social, courtly and stage dancing. It's a vague term, but therein lies its strength.

A similarly useful term can be found in the phrase French Country Dance . This term described a style of figure dancing performed socially in Britain of specifically French origin; such dances are usually arranged in a square formation, they arrived in England from the 1760s (I'm unaware of any earlier uses of the term in Britain, but won't be surprised if they do in fact exist). The phrase was used almost interchangeably with the term Cotillion (or Cotillon ) when that form of dancing first arrived in England; the term Cotillion came to take on a specific meaning in Britain (though it evolved in meaning over the decades), whereas French Country Dance remained a more neutral term without precise connotations. It was sufficiently broad to include such dances as would strain the stricter definitions of a Cotillion or Quadrille , including our La Batteuse. La Batteuse is an example of a French Country Dance that was briefly popular in England before the standard formula for the British Quadrille emerged. Some notable examples of off-formula Quadrilles did survive into the 1820s era, including such favourites as Les Graces and the original variant of La Pastorale. Other such dances include La Tempête and (perhaps) Le Boulanger. A representative collection of French Country Dances issued in 1815 by F.J. Klose is available here. The term French Country Dance can usefully be applied to this whole category of social dancing, without (much) terminological confusion. That said, the word French remains mildly prejudicial - it's as likely to imply as referred to in Britain as French as literally meaning from France . A further term of interest is the French Figure Dance , it sometimes referred to the Minuet and similar courtly dances, it was also in use in Britain throughout the same period. Yet another term of interest is Fancy Dance , a phrase that (according to F.J. Lambert in his 1815 treatise) referred to a choreographed dance in which the figures and music were so closely connected that it would be unthinkable to dance those figures to a different tune; a fancy dance may involve an exotic number of bars to a strain, or a crescendo, pause, or similar device at key moments in the figure. The Batteuse is not a fancy dance under this definition as several musical arrangements for the figures did exist.

Some early 19th Century references do exist to Figure Dances being performed at society Balls. In 1805 the Marchioness of Abercorn hosted a ball in which the first dance was a French figure-dance for two persons, performed in the same style as the Scots Strathspeys (The Morning Post, 25th February 1805). An 1810 ball hosted by Lady Campbell featured reels given with the true highland fling; likewise figure-dances, and German waltzes (The Morning Post, 2nd July 1810). It is recorded of the Countess of Shaftesbury's 1810 Ball that at half past five in the morning the dancing recommenced with a French figure dance by Lady B.A. Cowper (The Morning Post, 19th May 1810). Lady Saltoun held a Waltz Ball in 1815 in which Waltzing and French figure dances commenced at half past twelve . Numerous references to figure dances can be found in the advertisements for dancing masters of this period.

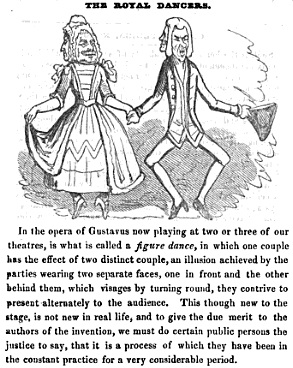

Figure 3. An 1833 Figure Dance on stage from Gustavus, Figaro in London 30th November 1833.

Figure dances could be performed by entire troupes of rehearsed dancers. Mrs Hope's Grand Ball in 1826 (The Morning Post, 1st May 1826) featured an example: The ball commenced at eleven o'clock, with a new Spanish figure dance, by sixteen beautiful young Ladies of fifteen: they were uniformly dressed in the high Castillian costume . That example involved a Spanish style of dancing; the 1809 A View of Spain described both the fandango and bolero Spanish dances as figure dances. Mr Farlo hosted a ball in 1790 which featured a Figure Dance, in which will be introduced the Military Manual Exercise, by a Party of Young Gentlemen, dressed in Uniforms and complete Accoutrements (Oxford Journal, 11th December 1790). Mr Hadwen's Ball in 1789 included a figure dance by three ladies (Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser, 1st April 1789). The Bachelor's Ball in Brighton in 1828 featured a figure dance involving eight ladies who were dressed precisely alike ... these eight danced a figure dance in which eight gentlemen, also dressed precisely alike, joined, and it was among the most attractive exhibitions of the evening (Brighton Gazette, 7th February 1828). A Mr. Sinclair in 1823 taught Figure Dances, for six, eight, ten, twelve, fourteen, and sixteen Ladies (Staffordshire Advertiser, 5th July 1823).

The term was also used to describe indigenous dances from around the world. The adventurer James Bruce in his 1790 Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile recorded a tribal dance from Abyssinia in which men sing the song, and dance the figure dance . Likewise Thomas Stamford Raffles described a dance from Java in his 1817 The History of Java as a figure dance of eight persons . The East India Company's Asiatic Journal and Monthly Miscellany in 1818 wrote of a dance in Ceylon in which young men performed a very regular figure dance, brandishing all the while and at each other, a couple of short sticks .

John Gardiner Wilkinson in his 1837 Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians wrote that a favourite figure dance was universally adopted throughout the country .

The term Figure Dance could also be applied to a solo demonstration of skill, such as performing a Hornpipe or Shawl dance. The 1827 novel High Life featured a ball in which Lady Isabel Ireton, to the admiration of some, envy of others, and slight surprise of all, performed by herself a beautiful figure dance, in which the splendid silver veil that hung about her was brought into frequent and graceful requisition . It could also be used to describe professional stage dancing, an example of which is depicted in Figure 3. The image shows dancers from the 1833 grand opera Gustavus by Auber; this particular figure dance featured the gimic of masked performers creating an optical illusion with a politically pertinent sentiment.

The link between these various different figure dances is that they all required practice. An untrained dancer couldn't simply give it a go, they needed to have memorised the choreography (i.e. the figures ) in advance. This was slightly less true for Quadrille dances, most of which were arranged so that four confident dancers performed first, and the others could then copy them; but at least some of the dancers did have to know the figures, even for a Quadrille.

It remained relatively common in the Regency era for public Balls to be commenced with a Figure Dance in the form of a courtly minuet; a lead couple, often the dancing master who was presiding over the ball together with a star pupil, would demonstrate their prowess to the admiring audience, before opening the floor to general social dancing. Figure dances were also a staple part of the various juvenile dancing academies; children would be taught routines, and would display what they'd learnt at a dancing-masters ball, presumably to the applause of their family and friends.

The figure dance could take many diverse forms.

Benjamin Towle's Figure Dances, 1759

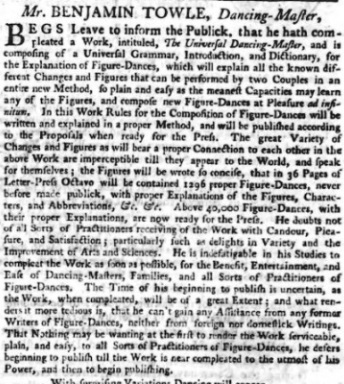

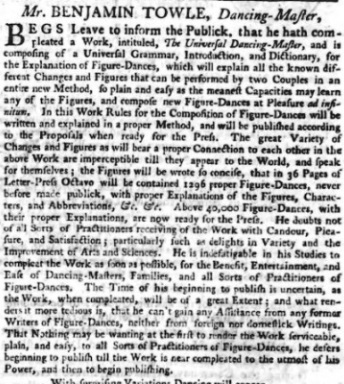

Figure 4. Towle's advert, Oxford Journal, 10th November 1759 Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive ( www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

A Dancing Master named Benjamin Towle began working on what could have been an important text on English figure dancing in 1759, unfortunately the book seems not to have been published. A discussion of that work is a little out of context here, but it seems a shame not to mention it. Benjamin Towle was a member of a successful family of Dancing Masters in the Oxford area, the family were active throughout much of the 18th Century. Benjamin published his Universal Dancing Master in 1759, then began work on a sequel. The law interrupted however; he was accused of assaulting several of his female pupils in 1760, convicted and pilloried, and sentenced to three months in prison (Oxford Journal, 19th July 1760): Decency will not permit us to enter into a particular Detail of the Wretch's Guilt, which seems to be an execrable Refinement upon that horrid Vice, and is attended with very extraordinary Circumstances . I've been unable to trace him thereafter, the conviction presumably disrupted his plans to publish.

He had previously shared his intentions, perhaps with a view to receiving subscriptions, in the Oxford Journal, 10th November 1759 (see Figure 4):

Mr. BENJAMIN TOWLE, Dancing-Master, BEGS Leave to inform the Publick, that he hath completed a Work, intituled, The Universal Dancing-Master , and is composing of a Universal Grammar, Introduction, and Dictionary, for the Explanation of Figure-Dances, which will explain all the known different Changes and Figures that can be performed by two Couples in an entire new Method, so plain and easy as the meanest Capacities may learn any of the Figures, and compose new Figure-Dances at Pleasure ad infinitum. In this Work Rules for the Composition of Figure-Dances will be written and explained in a proper Method, and will be published according to the Proposals when ready for the Press. The great Variety of Changes and Figures as will bear a proper Connection to each other in the above Work are imperceptible till they appear to the World, and speak for themselves; the Figures will be wrote so concise, that in 36 Pages of Letter-Press Octavo will be contained 1296 proper Figure-Dances, never before made publick, with proper Explanations of the Figures, Characters, and Abbreviations, &c, &c. Above 40,000 Figure-Dances, with their proper Explanations, are now ready for the Press. He doubts not of all Sorts of Practitioners receiving of the Work with Candour, Pleasure, and Satisfaction; particularly such as delights in Variety and the Improvement of Arts and Sciences. He is indefatigable in his Studies to compleat the Work as soon as possible, for the Benefit, Entertainment, and Ease of Dancing-Masters, Families, and all Sorts of Practitioners of Figure-Dances. The Time of his beginning to publish is uncertain, as the Work, when compleated, will be of a great Extent; and what renders it more tedious is, that he can't gain any Assistance from any former Writers of Figure-Dances, neither from foreign or domestick Writings. That Nothing may be wanting as the first to render the Work serviceable, plain, and easy, to all Sorts of Practitioners of Figure-Dances, he defers beginning to publish till the Work is near compleated to the utmost of his Power, and then to begin publishing.

Perhaps the work, or some portion of it, was in fact published. If you know more please do get in touch! It's one of my great disappointments to find a reference this detailed only for the associated publication to appear to have been lost... sadly this isn't the only such example. Towle mentioned that his choreographies are for two couples and involve changes and figures , terminology that is often associated with Cotillions, Allemandes and early Quadrilles. The book may have documented an early form of the Allemande dance that would subsequently be danced in Britain from the mid 1760s.

Matthew Towle, one of Benjamin's relatives (probably his Nephew), published his own Young Gentleman and Lady's Private Tutor in 1768 (Oxford Journal, 19th March 1768). It contained detailed information on deportment and on the dancing of the Minuet. It may have been influenced by Benjamin's work.

Popularity of La Batteuse

The Batteuse is a specific and named example of a figure dance, it combined a tune with a set of figures that were to be performed together. It's unusual to find historical evidence of named social dances being enjoyed - we generally just know the categories of dance: Waltz, Quadrille, Country Dance, etc.. But unusually, with La Batteuse, a reasonable amount of evidence of it being danced does exist; sufficient to know that it was popular, and that casual written references to it would be understood by contemporary readers.

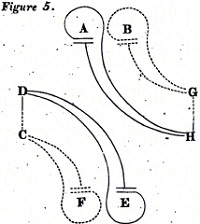

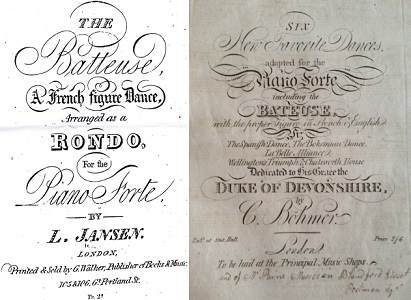

Figure 5. The covers of Louis Jansen's c.1815 The Batteuse, and Böhmer's c.1815 Six New Favorite Dances

First Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.232.c.(30.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The earliest reference I know of to La Batteuse being danced in England is from 1812. The Morning Chronicle reported: Mrs Coke again opened her elegantly-ornamented house, in Old Burlington-street, to a select few of her fashionable friends. The Waltz and Bateuse were the only dances thought worthy of the skill of our beautiful hostess and her two lovely daughters, who, until a very late hour, beat times to the fascinating strains of the Life Guards Band, which attended on the occasion. (The Morning Chronicle, 21st May 1812). As we shall see, the beating of hands is an essential characteristic of La Batteuse, and the source of the name itself.

The dancing master Mr Palmer from Liverpool advertised in 1815 (Liverpool Mercury, 17th February 1815) that Mr. P. having recently visited London, has acquired the most fashionable stile of teaching French and Russian Waltz, also those popular and elegant Dances, the Sauteuse and Batteuse, so highly approved in the first Circles . It was probably also in 1815 that Louis Jansen published his The Batteuse, a French Figure Dance, arranged as a Rondo (see Figure 5), and that Nathaniel Gow published music for La Batteuse in his 6 Favorite Dances of 1815. Gow went on to publish further music for The Batteuse in his 1816 Waterloo Medley publication, the cover of which strongly implied that it was danced at a Ball he held in January of that year.

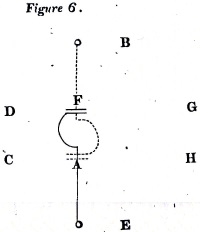

An 1816 playbill for the burletta Joconde, or Le Prince Troubadour mentions that an intermediary Waltz and the fashionable Dance of LA BATTEUSE would be danced on stage as part of the performance. Martin Platts also included a version in his c.1816 10th Periodical Collection of Popular Dances, Waltzes, &c. (see figure 6). James Platts (they were probably brothers) had printed the music in his 1813 38th Collection of Popular Dances, and Skillern & Challoner described it as a much admired French Dance in their c.1812 18th Favorite Collection of Popular Country Dances. George Walker published it in his 1816 39th Number.

Some dancers were evidently struggling to dance La Batteuse as Thomas Wilson wrote specifically about their poor performance in his 1816 Companion to the Ball Room (the words could have been added in a subsequent edition after this date). He wrote:

The author has seen the Batteause attempted (and what was called danced) in a large Company, composed of Persons of the first Fashion, who instead of performing the Steps so necessarily adapted to the Dance, made a single Chassé answer to all the Purposes of the Dance, which reduced the Dance to nothing more than the Beating and the Figure, by which the Dance lost its principal Interest and Effect. From this Example, and the Dance (as being deprived of its Steps) looking so very easy, induced others to try it who had never learnt a Step, producing enough to bring any Dance, however good, into Contempt.

Despite this, Wilson went on to advertise his 1817 73rd Public Ball promising a full program, including La Batteuse, Boulanger, La Rondo, &c. (The Morning Post, 19th April 1817). A Mr Payne of Salisbury also advertised a Public Ball in 1818 that would feature the admired French Dances La Batteuse and Boulanger (Salisbury and Winchester Journal, 28th December 1818). It's curious that the advertisements for both balls mentioned the Batteuse and Boulanger together, these two dances do share some similarities. La Batteuse also appeared within the New Quadrilles list sold by J. Willis in Dublin in 1818 (Freeman's Journal, May 27th 1818), in Duval's First Set of Quadrilles (Dublin Evening Post, 18th March 1817), and in the repertoire of Mrs W. West in New York in 1817 (The New York Evening Post, 5th September 1817).

The 1818 novel A Year and a Day by Frances Brooke included the dancing of La Batteuse: a party of girls were dancing la batteuse in time to their own voices, professedly to warm themselves; but in reality to show off advantageously both their voices and their figures to a party of gentlemen who, crowding round the blazing fires, deprived the linked graces of any other hope of warmth . There may be a double meaning to the word figure in this context!

References are harder to find after this date, though as late as 1835 the dancing mistress Mrs Thomas of Newcastle continued to feature it in her repertoire (Newcastle Journal, 17th January 1835). It also resurfaced in the 1850s in the repertoire of Mr. Smart (Leicestershire Mercury, 22nd June 1850); a dancing master named Mr. Huet went on to mention the celebrated Portuguese Finale La Batteuse (North Devon Journal, 24th July 1856).

The music or instructions for La Batteuse were published in several different sources, but the most verbose was that of Thomas Wilson's 1817 La Batteuse. It was published shortly after the second edition of his Quadrille Instructor, the Repository of Arts in 1817 even suggested it was a sequel to that work. In reviewing Wilson's book, they wrote:

It treats very minutely on the correct execution of the quadrille called La Batteuse , and, like the Quadrille Instructor, assists the directions by choreographic figures. The tune, which Mr. W. has added, is of a peculiar construction, having ten bars in each strain.

The ten-bar musical strains, or multiples thereof, are one of the defining characteristics of La Batteuse; they are evident in almost all of the publications that include it (see, for example, Figures 6 and 7). Standard quadrilles used eight-bar strains, so this dance would be a distinctive hybrid, not quite a Quadrille (in the post-1818 sense), but clearly related. The 1817 date of Wilson's publication was a point in time when the standard formula for a British Quadrille had yet to gain acceptance, the dance could be referred to as a Quadrille despite failing to match the characteristics associated with later Quadrilles.

Some eight-bar variants of the music for La Batteuse do exist, specifically adapted for Country Dancing; an example can be found in Wheatstone's Elegant & Fashionable collection of 24 Country Dances for the Year 1814, another is in Martin Platts' c.1816 10th Periodical Collection of Popular Dances, Waltzes, &c. (this is in addition to the standard 10 bar arrangement published in that same collection, see Figure 6). A further example of an eight-bar variant can be found in the c.1816 Goulding D'Almaine Potter & Co's Select Collection of Country Dances, No 38; dating this work is mildly problematic, their 35th publication is known to date to mid 1815 (Morning Post, 8th July 1815), and the 37th includes a tune called St. Helena, so the 38th collection is likely to date to 1816.

A later hybrid variant of La Batteuse was also published by Thomas Wilson in his 1819 6th L'Assemblée Book (and also in some of his other publications for that year). He called the new version La Bateuse and arranged it as a Country Dance with an 8-bar A-strain followed by a 10-bar B-strain. The B-strain featured clapping and Pas de Basque steps, reminiscent of the primary Batteuse arrangement. This hybrid is interesting as being a-typical for a Country Dance, though it's unlikely to have been widely danced.

Returning to Wilson's main Batteuse arrangement, an 1817 review in The New Monthly Magazine added:

Notwithstanding the clear and copious manner of explaining the figures through eleven pages of this treatise, we were still at a loss for steps, when fortunately we discovered in a note at the bottom of page 4 that a knowledge of the steps is to be acquired of the author. So that we shall lose no time in hobbling to the Old Bailey to procure the proper information, and sip the Castalian stream at the fountain head. The melody of La Batteuse is, we believe, correct, but we would advise Mr. Wilson to get some musical friend to correct his basses.

There's an unfortunate irony in Wilson complaining in his 1816 Companion to the Ball Room that dancers were ignoring the steps that are so essential to La Batteuse, but then failing to fully document them in his own 1817 guide to the dance, resulting in a mixed review from an influential magazine.

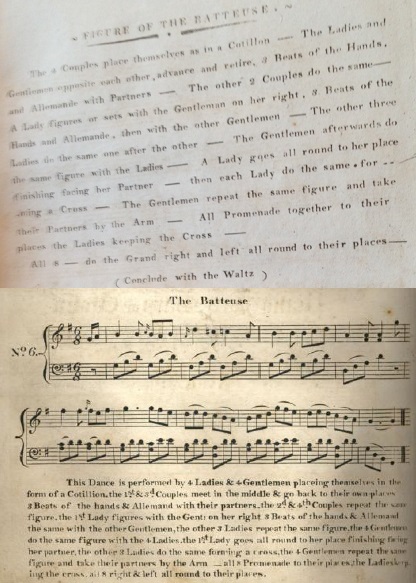

Variant versions of La Batteuse were also in circulation. For example, Böhmer's c.1815 Six New Favorite Dances (see Figure 6) included a slightly simpler version than that described by Wilson, the Martin Platts variant (also figure 6) matches that of Böhmer. Wilson's version may not have been the more widely danced variant, though it is the best documented.

Wilson's Introduction to La Batteuse

The following text is how Thomas Wilson introduced the dance in his book (the cover of which can be seen in Figure 7):

Figure 7. Thomas Wilson's 1817 La Batteuse, and the music from Böhmer's c.1815 The Batteuse

First Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.125.(34.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The great Celebrity which this Dance has so generally acquired in the first Circles of Fashion and the required frequentcy of its Introduction in all Fashionable Balls and Assemblies has rendered it necessary that every Teacher of Fashionable Dancing should become properly acquainted with it.

It has however since the Introduction of it as a Fashionable Dance suffered many Alterations which have tended to pervert the true Nature of its Composition as it correctly stands.

To obviate as much as possible any further Innovations on this pleasing Dance is the Author's object in laying down the correct Method of its performance by giving the proper Music, pointing out where the Steps and the Beating should be introduced, the Quantity of Music required for each, and shewing by Diagrams the Form of the Dance and the correct Manner of performing all the various Movements of which it is composed.

Old Bailey, London. T. Wilson. Feby 1817.

Directions to Dancers. The steps required in the performing of La Batteuse are but few, a correct knowledge of the following will be sufficient: Chassez, Jetté, Assemblé, Pas des Basque, Sauteuse Waltz Step. The tune will be found to contain ten bars in each Strain. Each Figure will require (performed by the proper Steps) exactly one Strain whether performed by Lady or Gentleman singly or by them together.

A Knowledge of the Steps as adapted to the various Movements of the Dance may be acquired of the Author 66 Old Bailey, Six Doors from Ludgate Hill.

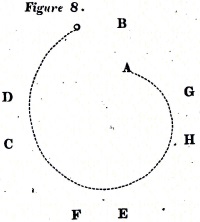

Wilson also provided two versions of the music, one called La Batteuse, and one called New Batteuse. The first was made up of 3 strains of 10 bars (the third strain repeating the first, but with a different bass line), the new version had two strains of 10 bars and a Da Capo. His new music was better adapted to emphasising where the Beating should occur, but for a dance with so much repetition I suspect the original might be more stimulating. Gow's version of the music only provided a single strain of 10 bars, which would be even more dull to dance to. Böhmer's music can be seen in Figure 7, it consists of a 10 bar A strain followed by a 20 bar B strain.

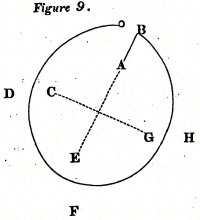

Wilson's Figures for La Batteuse

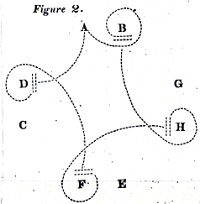

The table below shows the figures for La Batteuse, as supplied by Wilson himself. The images are his, as is the text. I've added the bar numbers in the left hand column. If I've interpreted it correctly, the dance requires 640 bars of music in order to be performed once through. This is in clear contrast to a typical Quadrille which might only require 128 bars (32*4 bars). Each dancer is required to perform solo dancing figures at various points in the dance, and specific steps are required.

It might be noticed that the Böhmer and Platts variants in Figure 6 require less than half of the music of Wilson's version. Alternative arrangements are clearly possible. It's unclear whether Wilson's version documents the popularly accepted version of the dance, or if he had documented his own arrangement. It's unusual for Wilson to provide such detailed information about dancing a specific dance, that he did so hints that La Batteuse was relatively popular, and that a market existed for this degree of detail.

| Bar Numbers |

Wilson's Image |

Wilson's Text |

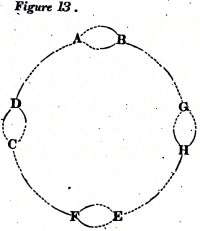

Bars 1-40 (10*4) |

|

The top Lady A makes 1 chassez to the Gentleman D, jetté et assemble, 2 Bars, 2 pas des Basque, 2 Bars, 3 jetté and at the same time 3 beats*, 2 bars, 3 Chassez jette et assemblé and turn the Gentleman D, 4 Bars, thus completing the 10 bars of which the Strain is composed.

The Lady A continues to perform the same Steps and Movements progressively with each Gentleman round to her place.

* This Mark * in the music shews where the Beating is introduced which is performed by gently beating one hand against the other up and down.

Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.125.(34.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

|

Bars 41-160 (40*3) |

|

The other Ladies in succession do the same.

|

Bars 161-320 (40*4) |

|

The Top Gentleman B performs the same Steps and Movements with all the Ladies commencing with Lady C round to his place.*

The other Gentleman respectively in succession do the same.

*The Gentlemens single Movements are occasionally omitted for the purpose of rendering the Dance shorter.

|

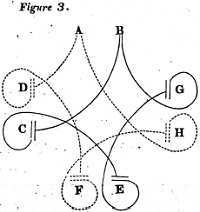

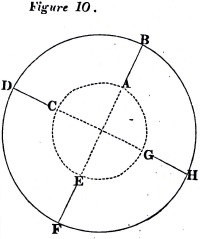

Bars 321-440 (30*4) |

|

The Top Lady and Gentleman A,B join hands and together perform the same Steps and Movements with all the Ladies and Gentlemen progressively round to places commencing with Lady & Gent C,D.

The other couples in succession do the same.

Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.125.(34.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

|

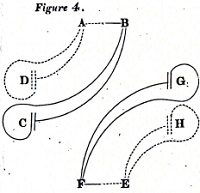

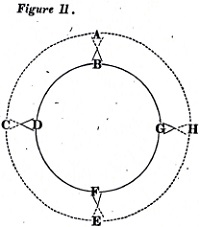

Bars 441-450 (10*1) |

|

Top Lady and Gent A,B perform the same Steps and Movements with Lady and Gent C,D. The Lady and Gent E,F at the same time perform the same Steps and Movements with the Lady and Gent G,H.

Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.125.(34.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

|

Bars 451-460 (10*1) |

|

The Lady and Gent C,D perform the same Steps and Movements with Lady and Gent E,F. The Lady and Gent G,H at the same time perform the same Steps and Movements with A,B.

Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.125.(34.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

|

Bars 461-466 (6*1) |

|

The opposite Lady A and Gent F (top and bottom) make one Chassez en avant (meet) jetté et assemblé, 2 bars, again one chassez jetté et assemblé and half turn, 2 bars, 3 jetté making at the same time 3 beats et assemblé, 2 bars.

Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.125.(34.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

|

Bars 467-470 (4*1) |

|

Join hands, 3 chassez (completely round and to places,) jetté et assemblé, 4 bars.

NB It will be seen that the 2 Diagrams have been necessary to elucidate the above it is but one Figure requiring 10 bars.

Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.125.(34.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

|

Bars 471-500 (10*3) |

|

Note: Wilson did not instruct to do this, but I suspect it's intended that the 3 remaining opposite couples perform the previous 10 bars, in turn. I suspect the ommission is a mistake; but feel free to leave out these 30 bars if you prefer to do so.

|

Bars 501-510 (10*1) |

|

The opposite Ladies and Gentleman (top and bottom) A,B and E,F perform the same Figure and Steps together, 10 bars.

|

Bars 511-520 (10*1) |

|

The opposite Ladies and Gentleman C,D and G,H do the same.

|

Bars 521-530 (10*1) |

|

The Lady A performs the Sauteuse Waltz* and finishes opposite to her partner B, 10 bars.

*For the acquirement of a knowledge of the Sauteuse Waltz the Author refers to his Description of German and French Waltzing Just Published.

Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.125.(34.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

|

Bars 531-560 (10*3) |

|

The other Ladies in succession do the same, finishing opposite to their respective partners, 10 bars each.

|

Bars 561-570 (10*1) |

|

The Ladies join hands across and the Gentleman B performs the Sauteuse Waltz, 10 bars.

Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.125.(34.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

|

Bars 571-600 (10*3) |

|

The other Gentlemen respectively and in succession do the same, 10 bars each.

|

Bars 601-610 (10*1) |

|

The Gentlemen join hands with their Partners and chassez round into places, 10 bars.

Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.125.(34.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

|

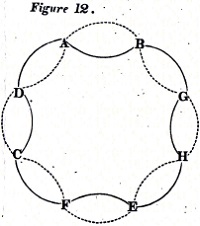

Bars 611-620 (10*1) |

|

All the Ladies join the hands of their respective partners and promenade round into places, 10 bars.

Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.125.(34.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

|

Bars 621-630 (10*1) |

|

All the Ladies and Gentlemen chain* round into places, 10 bars.

*In commencing the Chain Figure the respective partners give their right hands to each other and their left to the next person.

Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.125.(34.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

|

Bars 631-640 (10*1) |

|

All the Ladies join hands with their respective partners and perform the Sauteuse Waltz Step round into places, 10 bars.

Which finishes the Dance La Batteuse.

Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.125.(34.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

|

Wilson's publication was, perhaps, published a little too late. The dance was already going out of fashion, references to it are rare after 1818. The First Set of Quadrilles had captured the public imagination. New Quadrille choreographies were introduced at a rapid pace between 1816 and c.1822, they increasingly followed the conventions from the First Set. La Batteuse was briefly a Regency favourite but it was an anomaly and soon forgotten. It was one of the figure dances that competed with the early Quadrille, it lacked sufficient popularity to endure and is largely forgotten today.

That's where we'll end our investigation of this dance. If you have any further information to share, do please get in touch, we'd love to know more. If you do decide to dance La Batteuse, perhaps you could share a video of your group enjoying it?

|

Figure 1. Illustration for the 1820 L'Horatia figure dance from Belle Assemblée

Figure 1. Illustration for the 1820 L'Horatia figure dance from Belle Assemblée

Figure 2. Detail from a 1792 Print called Rehearsing a Cotilion; the dancers have sheets of paper with instructions

Figure 2. Detail from a 1792 Print called Rehearsing a Cotilion; the dancers have sheets of paper with instructions

Figure 3. An 1833 Figure Dance on stage from Gustavus, Figaro in London 30th November 1833.

Figure 3. An 1833 Figure Dance on stage from Gustavus, Figaro in London 30th November 1833.

Figure 4. Towle's advert, Oxford Journal, 10th November 1759

Figure 4. Towle's advert, Oxford Journal, 10th November 1759  Figure 5. The covers of Louis Jansen's c.1815 The Batteuse, and Böhmer's c.1815 Six New Favorite Dances

Figure 5. The covers of Louis Jansen's c.1815 The Batteuse, and Böhmer's c.1815 Six New Favorite Dances  Figure 6. Figure of the Batteuse from Böhmer's c.1815 Six New Favorite Dances (above) and Martin Platts' c.1816 10th Periodical Collection of Popular Dances, Waltzes, &c. (below)

Figure 6. Figure of the Batteuse from Böhmer's c.1815 Six New Favorite Dances (above) and Martin Platts' c.1816 10th Periodical Collection of Popular Dances, Waltzes, &c. (below)

Figure 7. Thomas Wilson's 1817 La Batteuse, and the music from Böhmer's c.1815 The Batteuse

Figure 7. Thomas Wilson's 1817 La Batteuse, and the music from Böhmer's c.1815 The Batteuse