| Return to Index | ||||

|

Paper 13 The Regency WaltzContributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 14th April 2015, Last Changed - 8th March 2024]The Waltz was a (literally) revolutionary dance that entered the British Assembly Halls from Europe during the greater Regency era. In this paper we'll consider the history of the dance in England, the controversy that surrounded it, and how it was danced. Back in 2018 I presented much of this information in the form of a paper at a Dance History conference. That paper is now available to read on the web courtesy of the Early Dance Circle, you can read it here.

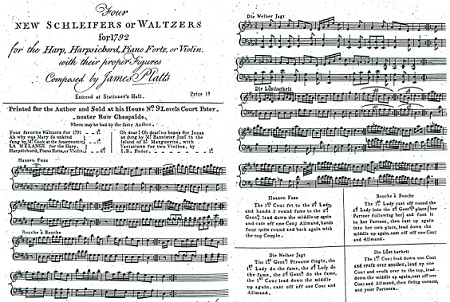

The Early Waltz, 1790-1809 Figure 1. Four New Schleifers or Waltzers for 1792, by James Platts.

Figure 1. Four New Schleifers or Waltzers for 1792, by James Platts. Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.149.(23.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The word Note: earlier references to waltzing are likely to emerge. For example, Thomas Skillern's 1787 Caledonian Medley Dance included a tune he named The Walse. It's in 2/4 measure, so not a triple-time waltz in the normal sense but it hints that the term was starting to become known in the 1780s. The first reference I know of in English can be found in the 1779 translation of one of Goethe's novels.

The first English publications consisting entirely of Waltzes were probably those of James Platts. Platts was a musician, composer, and also a publisher. He issued his first known collection in 1791 (The World, 26th January 1791), and followed it up with several similar works throughout the 1790s. He was the first to register Waltzes for copyright purposes at Stationers' Hall. Platts' second collection were published in 1792 (see Figure 1), he explicitly referred to them as

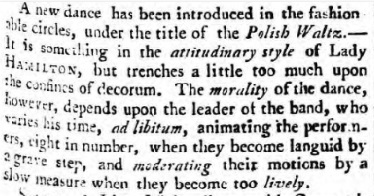

Other early references associate the Waltz with performance dancing on stage. In 1797 The Duke of Wirtemberg's Waltz was listed amongst a collection of Piano Forte music used at the King's Theatre Opera House (True Briton, 30th May 1797), and James Harvey D'Egville (or perhaps a younger relative) danced Waltzes at the Theatre Royal in 1800 (The Observer, 27th April 1800). A dancing master from Liverpool called Joseph Robinson advertised in 1800 that he had returned from the city of Bath where he had learnt the At some point during the 1790s the couple-Waltz emerged as a dance form in Britain. An early description can be found in The Morning Post for 8th April 1801 (see Figure 2), it reports: This early description associates the dance with Poland, though I don't consider that to be significant. Several characteristics of this specific Waltz are clear:A new dance has been introduced in the fashionable circles, under the title of the 'Polish Waltz'. It is something in the 'attitudinary style' of Lady HAMILTON, but trenches a little too much upon the confines of decorum. The 'morality' of the dance, however, depends upon the leader of the band, who varies his time, 'ad libitum', animating the performers, eight in number, when they become languid by a grave step, and 'moderating' their motions by a slow measure when they become too 'lively'.

attitudes, and was at the centre of a public scandal having given birth to Lord Nelson's daughter (despite being married to Sir William Hamilton). It's curious that this early reference should mention the word morality, the morality of the dance would continue to be called into question over the next couple of decades. A more subtle example of this disapproving attitude can be found in the Hampshire Chronicle for 12th May 1800; it reported that Two lovers of Harbourg, while dancing the Waltz on the night of the 16th of April, were killed by lightning, perhaps implying divine intervention! In a similar vein an article in The Sporting Magazine for April 1800 reported: Among the dances in our fashionable routes, the German Waltze has become so general, as to render the ladies' garters an object of consideration in regard to elegance and variety.

Figure 2. The Morning Post, 8th April 1801.

Figure 2. The Morning Post, 8th April 1801. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk) in which the men and women form a ring. Each man holding his partner round the waist, makes her whirl round with almost inconceivable rapidity: they dance in a grand circle, seeming to pursue one another: in the course of which they execute several leaps, and some particularly pleasing steps, when they turn, but so very difficult as to appear such even to professed dancers themselves. We've discussed the Allemande further in another Paper, it seems never to have been popular in Britain but may perhaps have eased the arrival of the Waltz.

An 1806 description of the Waltz appears in Busby's A Complete Dictionary of Music, it's defined as:

The Country Dance publisher William Campbell produced his 22nd collection c.1807; it includes a deceptively important dance called The Russian Ambassador's Waltz (With the original German Figure). His publication offers the first clear evidence I know of for Waltz like figures being introduced into a Country Dance. Campbell's

The first society ball I know of that featured a waltz dance was hosted by the Marchioness of Abercorn in 1801 (The Morning Post, 25th May 1801). It was opened with the

One early supporter of the Waltz may have been Lady Mary Bentinck. The Morning Post for the 25th March 1801 reported that she

Figure 3. Specimens of Waltzing, 1817.

Figure 3. Specimens of Waltzing, 1817. © Trustees of the British Museum Controversies, 1810-1812

As the Waltz increased in popularity, it also increased in controversy. This was true in Germany, and it remained true in England. The German author Goethe mentioned the Waltz in his 1774 Sorrows of Young Werther; the character vows To see so many lovely and elegant young women moving with grace and activity, their charming faces light up with pleasure, and their eyes sparkling at the admiration they excited, was, to an old fellow like me, a sight truly delightful, though I could not help agreeing with Werter, who said, his wife should never dance a waltz. The partners of those lovely creatures, said I, mentally, must be very happy; for though dignity and good-breeding preserved the most perfect delicacy in each, yet I still agreed with Werter, that my wife, if ever I have one, shall never dance a waltz, though it was charming to see the angels fly down the room as if they had already wings.

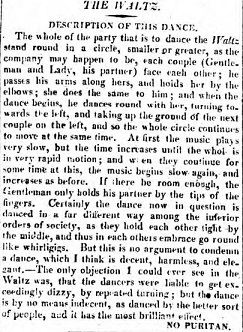

An extended debate took place within the columns of the Morning Post newspaper in 1811 regarding the Waltz. A particularly helpful letter to the editor was printed on the 5th August (see Figure 4), it aimed to demystify the Waltz. In so doing, it provides the most detailed description of the Waltz I know of in English, prior to the publications of Thomas Wilson. It was signed Several aspects of this Waltz are notable:The whole of the party that is to dance the Waltz stand round in a circle, smaller or greater, as the company may happen to be, each couple (Gentleman and Lady, his partner) face each other; he passes his arms along hers, and holds her by the elbows; she does the same to him; and when the dance begins, he dances round with her, turning towards the left, and taking up the ground of the next couple on the left, and so the whole circle continues to move at the same time. At first the music plays very slow, but the time increases until the whole is in very rapid motion; and when they continue for some time at this, the music begins to slow again, and increases as before. If there be room enough, the Gentleman holds his partner by the tips of the fingers. Certainly the dance now in question is danced in a far different way among the inferior orders of society, as they hold each other tight by the middle, and thus in each others embrace go round like whirligigs. But this is no argument to condemn a dance, which I think is decent, harmless, and elegant. The only objection I could ever see in the Waltz was, that the dancers were liable to get exceedingly dizzy, by repeated turning; but the dance is by no means indecent, as danced by the better sort of people, and it has the most brilliant effect.  Figure 4. The Morning Post, 5th August 1811

Figure 4. The Morning Post, 5th August 1811 Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

No Puritan's letter appeared in the middle of an extended debate spanning many issues of the newspaper. It solicited an immediate reply on the 7th August 1811 from a moralist who signed themselves Perhaps the crux of the problem was that the Waltz was an overly sensual dance that made the dancers giddy and disorientated, it also encouraged (or at least tolerated) uninterrupted eye contact. Such behaviour might have been dangerous in the sexually charged environment of the marriage-mart Assembly Halls.

Another anti-waltzist calling themselves A Friend to the Public Morals writing in the Morning Post on the 27th July 1811 warned A poem ascribed (with some uncertainty) to the Irish playwright Sheridan was also repeated in numerous publications in 1811 and 1812: How arts improve in this degenerate age!  Figure 5. Inconvenient Partners in Waltzing, 1819. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Figure 5. Inconvenient Partners in Waltzing, 1819. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

The poem repeats the anti-waltz message that seems to have dominated public opinion at this time. The Waltz remained a topic of controversy however; for example, several newspapers in 1812 reported on a duel fought over the Waltz. The Edinburgh Advertiser for the 28th July 1812 records: Lord Byron wrote his infamous anti-Waltz poem Waltz, An Apostrophic Hymn in 1812, it was published anonymously and advertised for sale in The Morning Post newspaper on the 26th February 1813. Byron had his own motivations for publishing of course but his authority being added to the anti-waltz movement was considered to be significant.

The author of the 1811 etiquette guide The Mirror of the Graces considered the Waltz to be unsuitable for unmarried ladies:

But despite the anti-waltzing lobby, the aristocracy continued to Waltz. The Countess of Shaftesbury held a Ball in 1810 attended by 320 fashionables at which a Waltz Medley was danced (Morning Post, 19th May 1810). Socialite Mrs Calvert (1767-1859) wrote in her journal for the 12th of May 1811 that

Acceptance, 1813-1819 Figure 6. Waltzing, 1815.

Figure 6. Waltzing, 1815. © Trustees of the British Museum

The diarist Thomas Raikes recorded in 1835 that Sir, Some lines appeared in your paper a few days ago upon the subject of Waltzing, with the initials of 'Sir H. E.' affixed to them. They certainly contained heavy charges of impropriety against those Ladies who practise that dance - such as in the following lines:-

The words of Sir H.E. (probably Sir George Dallas) were subsequently used to accompany the anti-waltz image in Figure 6. The reply in the Chronicle hints at a subtle shift in social mores, the Waltz was growing in acceptance. An 1819 novel called The Hermit in London offered some sensible advice to a young lady keen to waltz:

Figure 7. Waltzing at Almacks, c.1817.

Figure 7. Waltzing at Almacks, c.1817. © Trustees of the British Museum The Emperor Alexander waltzed with at least ten young ladies, selecting his partners for their shape and beauty, regardless of their rank or distinction. The company began to dance at half past twelve o'clock, led off with waltzes by the Emperor and the beautiful Countess of Jersey. The young Prussian Princes were likewise amongst the first who danced. There were waltzing parties at the upper end of the ball-room, and country-dances below.. This Ball is of particular relevance to modern fans of Jane Austen as she wrote to her sister Cassandra of their Brother Henry Austen being in attendance! English references to the Waltz tended to be more neutral in tone following this state visit (with a few important exceptions that we'll come to); the Waltz was often referred to as a Russian dance in such later references. As an example, consider an advertisement published in the Liverpool Mercury (23rd October 1814) for a dancing master named Mr Yates, it began: As the present style of Dancing is different to what it was since the Emperor of Russia has made Waltzes and Waltz Country Dances so general by his Dancing them while he was in London, Mr Yates has had many applications to teach them;. The public opinion was shifting. The most elite of Regency London's fashionable dancing venues was Almack's Assembly Rooms. It's unclear exactly when Waltzes were first introduced at Almacks but they were danced there from at least the year 1815 (Morning Post, 6th May 1815), perhaps following the Tsar's visit. The image in Figure 7 is believed to show Lord Kirkcudbright waltzing with Lady Jersey at Almack's in 1817, this is the same Lady Jersey who opened the Ball at Burlington House in 1814 by Waltzing with the Tsar. If the image is to be taken literally, it shows that Almacks' fashionable dancers were waltzing with a more permissive arm-around-the-waist embrace than referenced in the earlier publications. The inroduction of waltzing at Almacks was of social significance; the anonymous author of an 1860s retrospective Recollections of Almacks described the introduction of the waltz: Thomas Raikes in his diary also mentioned the introduction of Waltzing at Almack's:Modestly, at first, did young men and maidens, who had scarcely so much as shaken hands, come into contact tender enough for affianced lovers. Deeply did virtuous matrons blush whilst worthy fathers looked in from the card-room with horror on their roseate faces; but being assured that all was right, and my Lady Sophy Lindamell had waltzed away, first of all with Captain Cutbush, went back again with an air of resignation to their long whist. It is very long since matrons have ceased to blush when they see their young daughters carried off in the whirl of some human teetotum. They blush only, and with resentment too, when their blooming daughters are suffered to sit still. What scenes have we witnessed in those days at Almacks', &c.! What fear and trembling in the debutantes at the commencement of a waltz, what giddiness and confusion at the end!.

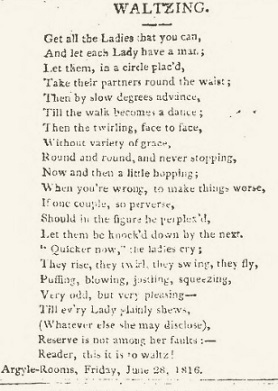

The 1815 novel Rhoda (advertised in The Gloucester Journal, 16th October 1815) by Frances Jacson featured an eponymous character who struggled with the morality of the Waltz before eventually succumbing to temptation: A poetic description of the Waltz was published in The Star, 5th July 1816 (see Figure 8). The Star in turn associates it with the Argyll Rooms on the 28th June 1816, perhaps describing a raucous Waltz party that was actually held there. It reads:

Figure 8. Waltzing at the Argyll Rooms, The Star, 5th July 1816. (Courtesy of NewspaperArchive.com )

Figure 8. Waltzing at the Argyll Rooms, The Star, 5th July 1816. (Courtesy of NewspaperArchive.com )

This describes a (perhaps) less socially acceptable form of waltzing. The characteristics include:Get all the Ladies that you can,

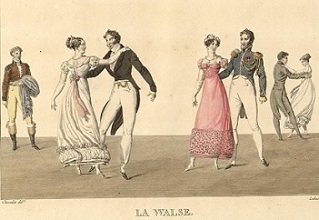

The poem was published at around the same time that The Times newspaper (16th July 1816) published a strong anti-waltzing statement after the Waltz was danced at Court:  Figure 9. La Walse,

Étrennes à Terpsichore, Marque, 1821.

Figure 9. La Walse,

Étrennes à Terpsichore, Marque, 1821. Courtesy of Biblioteca Nacional de España.

Opinions regarding the Waltz can (perhaps) be seen to differ between the different social stratas of London society. The dancing master Thomas Wilson wrote about this in the preface to his 1816 The Correct Method of Waltzing. He began by admitting that most English dancers He ascribed the anti-waltz sentiment to prejudice but wrote thatYet Waltzing, since its origin, has ever been a particularly favorite amusement in the higher circles of fashion; and from the recent influx of foreigners into this country, and the visits of the English to the continent, where Waltzing, as well as every other species of Dancing, are much more indulged in than in this country, it has now become much more fashionable with us. its favoritism has considerably increased with its practice. He concluded that Waltzing, notwithstanding all the opposition its more extensive practice has had to encounter, is now generally considered so chaste, in comparison with Country Dancing, Cotillions, or any other species of Dancing, that... Waltzing is more frequently substituted for Country Dancing, than the latter is for the former.

A further class difference can be seen in an anecdote published in The Ton (advertised in The Morning Post, 17th December 1818). It reports: A Ball at the Royal Pavilion in Brighton in 1817 also featured a Waltz (Morning Chronicle, 20th January 1817). It was hosted in honour of Duke Nicholas of Russia, the report includes an interesting detail: Marching or Promenading around the room prior to a waltz was common, on this occasion a specifically Russian style of marching was introduced. The Polonaise was a formal parade of dignitaries, it was a form of movement that had been growing in popularity since its great success at the balls of the 1814 Congress of Vienna.His Imperial Highness, as adopted in Russia, preceded the waltz with a Polonaise march and step, in which the dancers move round the space allotted for the exercise in graceful motion, ere the more intricate varieties of the waltz are pursued.

An interesting annecode from 1822 is preserved in The London Magazine. It recorded an elegant little ball on board a ship. The Master of Ceremonies, Colonel St. Etienne, wished to begin the ball with a waltz;  Figure 10 Waltzing, 1825. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Figure 10 Waltzing, 1825. Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

An 1822 poem in The New Monthly Magazine described a Waltz danced at a private gathering: First, Richard and I, like a proper taught pair, The advice for avoiding giddiness is of particular interest. Society was changing, and had changed. So much so that in 1819 the Cheltenham Chronicle published a reminder that the old Country Dances shouldn't be forgotten amidst the fervour of Waltzing and Quadrilling: Sir, I am sure you will not refuse to give a place in your paper to the humble demonstrance and petition of an ill-treated family, of genuine British origin: and in this seat of Mirth, Harmony, and Good-humour, where the natives of the principal portion of the king's domains, live together like members of one family; I hope your readers will view with pity and compassion the case of three injured sisters: and that the 'formal Quadrille' and 'immodest Waltz', shall no longer be suffered to drive from their recollection their old favourites, THE IRISH, SCOTCH and ENGLISH COUNTRY DANCES.

Waltzing with the Dancing MastersSo far we've been able to discuss the Waltz with almost no reference to the publications of the dancing masters. At this point I have to admit to a slightly heretical opinion... I don't think most dancers 200 years ago much cared for the tuition and finesse of dancing masters! The Waltz, as with all social dances, is primarily danced for enjoyment, and so long as dancers have an ear for the music and some degree of timing, precise stepping isn't particularly important. However, if you wanted to pay for tuition, there was no shortage of masters prepared to accept your money.

The primary publication that documents the Waltzes of the Regency era is the 1816 The Correct Method of Waltzing by Thomas Wilson. Wilson also published an 1817 work called Le Moulinet, the Allemande and the Waltz Quadrilles, I'm unaware of any surviving copies of the second work. Wilson was influential in popularising the Waltz, La Belle Assemblée in 1817 wrote

Wilson defined two categories of Waltz, those of the  Figure 11. Waltzing! or a peep into the Royal Brothel, 1816

Figure 11. Waltzing! or a peep into the Royal Brothel, 1816 © Trustees of the British Museum

Wilson promoted many different waltzing embraces, the elbow and finger-tip holds weren't the only elegant options (see Figure 13, Figure 2, Figure 9, Figure 10 & Figure 12). He suggested that waltzing partners should be selected for their similarity in height, and emphasised the need for balance and mutual support; waltzers should not

Wilson was also responsible for publishing collections of Wilson's claim to have invented the Waltz Country Dance is not without controversy; the imperial Russian state visit in 1814 was also reported to have introduced this hybrid convention to London (e.g. Liverpool Mercury, 23rd October 1814), so Wilson may have adapted the Russian style of Waltzing.N.B. To render this species of Music more useful to the dancer & more general in its application than waltzes now published are, the Author has set to them a few figures entirely adapted to that new & elegant system of dancing called Country dance Waltzing, or Waltz Country Dancing.

Wilson was also known for choreographing waltz medleys for display or stage purposes. He arranged a Valentine Waltz in which He elsewhere described a perhaps similar form of display waltzing as The English Waltz, something he'd arranged for 48 dancers (see the advertisement at the back of his 1821 The Address) and considered to be a new dance form of his own invention.Twelve pretty young Ladies the dance will perform,

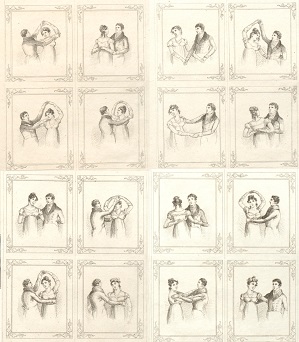

Other dancing masters were also active in teaching and experimenting with the Waltz. Edward Payne published a collection of Waltzes c.1816 that were probably the first Waltz Quadrilles in England; he also pioneered the Spanish Country Dances that were influenced by the Waltz from around 1816. He taught at least three variants of the waltz in early 1816: One important further source is the Lowes' Ball-Conductor & Assembly Guide, the first two editions of which were published in Glasgow in 1822; the later third edition described eight waltz holds. The Lowes were a family of dancing masters with academies across Scotland; I've quoted from the 1831 third edition. They offer the following waltz embraces:  Figure 12. G.M.S. Chivers' 16 Divisions of Waltzing, c.1822.

Figure 12. G.M.S. Chivers' 16 Divisions of Waltzing, c.1822.Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, 558*.c.40 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

It has been of late fashionable to dance waltzes so fast, that only the first and second of the foregoing figures can be used; but when the waltz is performed slowly, as it ought to be, the whole may be used, and many more.They went on to mention three waltz steps, though the reference to the Gallopadedates these descriptions to c.1830:

Several other publications discussed the various Waltz steps at this date, the most prominent being Wilson's The Correct Method of Waltzing. Edward Payne also documented the Waltz and Promenade steps in his 1818 Instructions for Spanish Dancing. His descriptions aren't readily available elsewhere, so I've quoted them here:

Waltz dance music was often associated with Quadrille dancing. Most Quadrille publications of the 1810s and 1820s also included an example Waltz tune in addition to the promised Quadrille Set, and

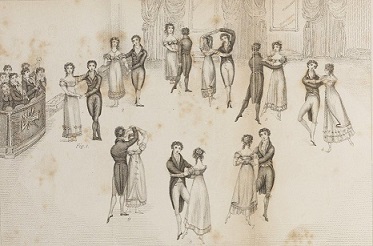

R. Hill, author of the 1822 A Guide to the Ball Room (I'm quoting from the 1830 edition) wrote of the Waltz: The elegance of the Waltz is something the Dancing Masters clearly emphasised. Wilson included the following passage in his 1821 The Address commenting on the poor performance of some dancers: It is too frequently observed, that in public assemblies, persons are to be found, who not only Waltz in an awkward and inelegant manner; but by hugging and dancing so close to their partners, stamping with their feet, bending forward at their knees, and poking out their elbows, disgust the spectators, and prove unpleasant to their partners; this method of Waltzing is not only objectionable to the company, but tends to bring this elegant species of Dancing into disrepute, which if well performed according to the Rules laid down, will be found to be one of the most elegant and interesting departments of the art. It is not alone sufficient to make a good Waltzer, to have a correct knowledge of the steps, or a brilliant execution of the feet; but they must be united with a graceful carriage of the head and arms, and an easy and elegant deportment of the person. Wilson of course hoped to sell his own tuition (and books), and thereby improve the English waltzer. The anonymous A Gentleman in his 1823 Etiquette of the Ball-Room commented on the process by which the Waltz came to be accepted in England:  Figure 13. Wilson's Waltz figures, 1816, from A Description of the Correct Method of Waltzing

Figure 13. Wilson's Waltz figures, 1816, from A Description of the Correct Method of Waltzing Courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France. The English providedWhen Waltzing first its fashion found, graceful movementsfor the Waltz, and gradually the dance was Anglicised. But the process of acceptance changed the English nation itself, intimate couple-dances remained popular throughout the 19th Century.

If you'd like to learn more about the early Waltz, I'd recommend reading Thomas Wilson's 1816 A Description of the Correct Method of Waltzing. I can also recommend Volume 7 of John Gardiner-Garden's Historic Dance, and Susan de Guardiola's Capering & Kickery blog. On a more practical level I can recommend Waltzing, A Manual for Dancing and Living by Richard Powers and Nick Enge. If you'd like to see some Regency era Waltz music, I've shared a copy of Monro's c.1818 Waltziana from my personal collection here. Finally, if you'd like to read the paper on Waltz history that I presented at a Dance History conference back in 2018, you can you can read it here.

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved